Search by Keyword

Sign Up Below for our MONTHLY BEATLES TRIVIA QUIZ!

|

“ELEANOR RIGBY”

(John Lennon – Paul McCartney)

“I don’t think we ever try to establish trends. We'd try to keep moving forward and do something different.” This quote from McCartney in 1966 typifies the insistent "forward movement" attitude that became The Beatles creed, especially from that year onward. While seemingly every move they had made musically did indeed become the new “trend” that was being imitated by anyone desirous of making their mark on the charts, their objective was simply to be innovative for innovation's sake. “I don’t think we ever try to establish trends. We'd try to keep moving forward and do something different.” This quote from McCartney in 1966 typifies the insistent "forward movement" attitude that became The Beatles creed, especially from that year onward. While seemingly every move they had made musically did indeed become the new “trend” that was being imitated by anyone desirous of making their mark on the charts, their objective was simply to be innovative for innovation's sake.

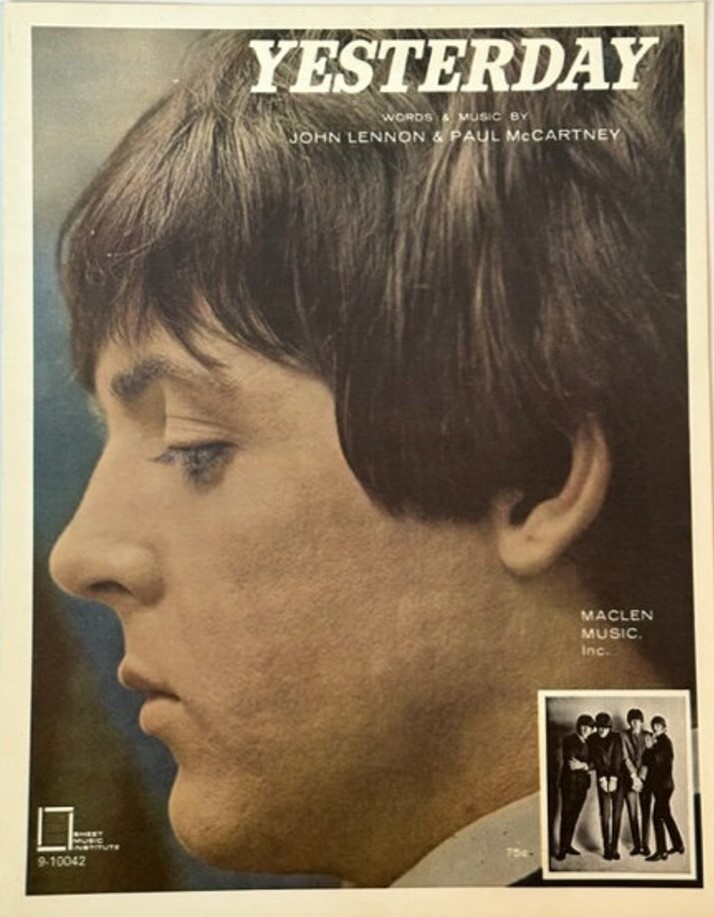

Unwittingly, they topped themselves by taking the previous step forward of “Yesterday,” with its string quartet backdrop to Paul’s acoustic guitar and solo vocal, to the giant leap of a double string quartet playing a classically written score put together by Paul and producer George Martin and no Beatles instrumentation whatsoever. This did not start a “trend,” as it were, but only made the competition drop their jaws in awe, leaving everyone in the dust! “Eleanor Rigby” appeared as the master stroke that revealed The Beatles as above and beyond all of their contemporaries. Unwittingly, they topped themselves by taking the previous step forward of “Yesterday,” with its string quartet backdrop to Paul’s acoustic guitar and solo vocal, to the giant leap of a double string quartet playing a classically written score put together by Paul and producer George Martin and no Beatles instrumentation whatsoever. This did not start a “trend,” as it were, but only made the competition drop their jaws in awe, leaving everyone in the dust! “Eleanor Rigby” appeared as the master stroke that revealed The Beatles as above and beyond all of their contemporaries.

Gravestone with the name "Eleanor Rigby" as found in Woolton Cemetary, Liverpool

|

Songwriting History

Research done to spell out the songwriting history of most Beatles songs reveals many interesting details, convincing testimony related from eyewitnesses and the writers themselves settling the matter once and for all. There may be conflicting details unearthed from interviews that cast doubt on some aspects, but overall the reader can get a clear enough picture to understand the general formation of that particular composition. A detailed quote right from "the horse’s mouth" is usually enough to squelch previously conceived ideas the listener may have held for many years. Research done to spell out the songwriting history of most Beatles songs reveals many interesting details, convincing testimony related from eyewitnesses and the writers themselves settling the matter once and for all. There may be conflicting details unearthed from interviews that cast doubt on some aspects, but overall the reader can get a clear enough picture to understand the general formation of that particular composition. A detailed quote right from "the horse’s mouth" is usually enough to squelch previously conceived ideas the listener may have held for many years.

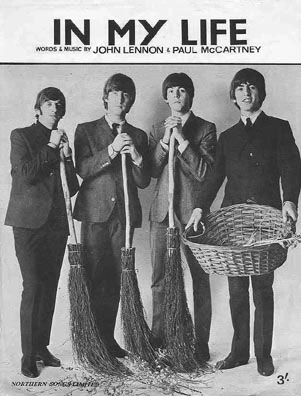

However, the inspiration and construction of “Eleanor Rigby” to get it to the finished state as we know it is quite a complicated task to decipher, one that goes much deeper than "who wrote what" and "when." While there is a general discrepancy between the separate interviews of Lennon and McCartney regarding the classic song “In My Life,” the song under discussion here marks the most ambiguous of all Beatles songs with an abundance of details from various sources that sometimes add up to a harmonious picture but sometimes contradict entirely. However, the inspiration and construction of “Eleanor Rigby” to get it to the finished state as we know it is quite a complicated task to decipher, one that goes much deeper than "who wrote what" and "when." While there is a general discrepancy between the separate interviews of Lennon and McCartney regarding the classic song “In My Life,” the song under discussion here marks the most ambiguous of all Beatles songs with an abundance of details from various sources that sometimes add up to a harmonious picture but sometimes contradict entirely.

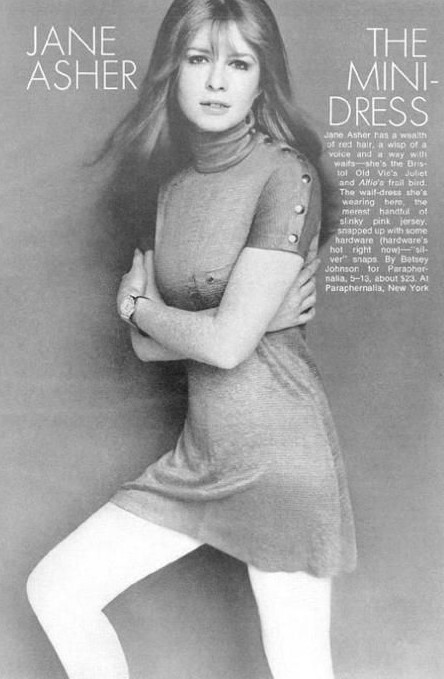

The story starts simply enough from, as Paul’s book “Many Years From Now” attests, him beginning to write the song in the “little music room” in the Asher home at 57 Wimpole Street, London, where he was staying as a live-in guest with his current girlfriend Jane Asher. While many other Beatles classics were at least partially composed in this room (including “I Want To Hold Your Hand”), this one had much more work to be done to it before being deemed complete. The story starts simply enough from, as Paul’s book “Many Years From Now” attests, him beginning to write the song in the “little music room” in the Asher home at 57 Wimpole Street, London, where he was staying as a live-in guest with his current girlfriend Jane Asher. While many other Beatles classics were at least partially composed in this room (including “I Want To Hold Your Hand”), this one had much more work to be done to it before being deemed complete.

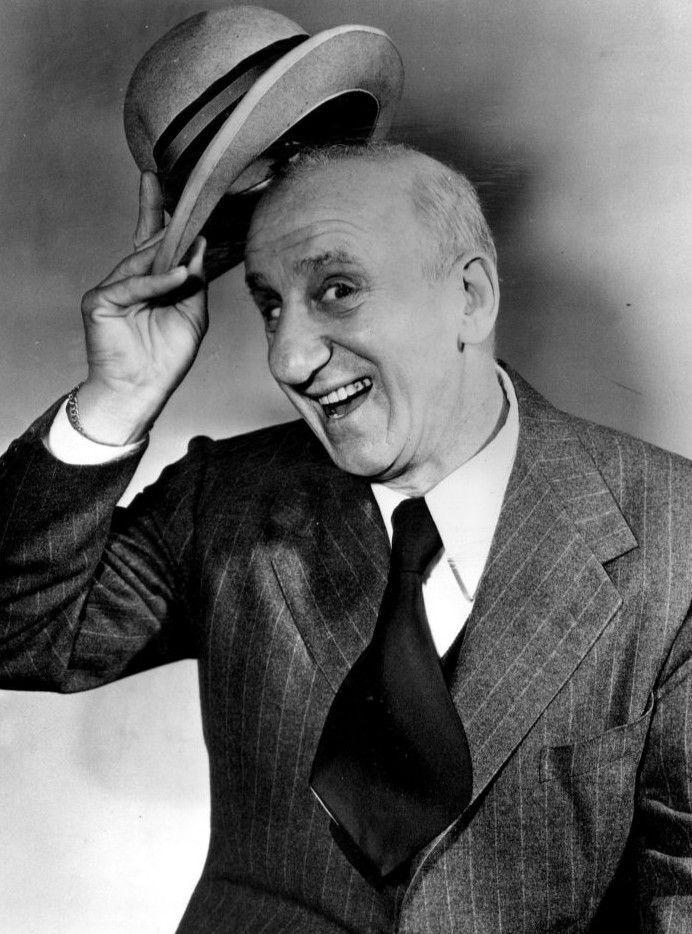

“I was sitting at the piano when I thought of it,” recalls Paul, “just like the comedian Jimmy Durante. The first few bars just came to me, and I got this name in my head – Daisy Hawkins, she picks up the rice in the church where a wedding has been…Those words just fell out like stream-of-consciousness stuff, but they started to set the tone of it all, because you then have to ask yourself, what did I mean? It’s a strange thing to do: most people leave the rice there, unless she’s a cleaner. So there’s a possibility she’s a cleaner, in the church, or is it a little more poignant than that? She might be some lonely spinster of this parish who’s not going to get a wedding, and that was what I chose. So this became a song about lonely people.” “I was sitting at the piano when I thought of it,” recalls Paul, “just like the comedian Jimmy Durante. The first few bars just came to me, and I got this name in my head – Daisy Hawkins, she picks up the rice in the church where a wedding has been…Those words just fell out like stream-of-consciousness stuff, but they started to set the tone of it all, because you then have to ask yourself, what did I mean? It’s a strange thing to do: most people leave the rice there, unless she’s a cleaner. So there’s a possibility she’s a cleaner, in the church, or is it a little more poignant than that? She might be some lonely spinster of this parish who’s not going to get a wedding, and that was what I chose. So this became a song about lonely people.”

“I knew quite a lot about old people,” Paul continues, "I was a Boy Scout and I often visted local pensioners as a good deed. I used to think it was the right thing to do – I still do, actually – but what I’m saying is, I wasn’t ashamed to go round and ask someone if they wanted me to go the doctor’s for them or to help old ladies across the road. It had been instilled into me that that was a good deed. So I sat with lots of old ladies who chatted about the war and all this stuff, and also, as I fancied myself as a writer, a part of me was getting material. There was a corner of my brain that used to enjoy that kind of thing, building a repertoire of people and thoughts. Obviously writers are always attracted to detail: the lonely old person opening her can of cat food and eating it herself, the smell of the cat food, the mess in her room, her worrying always about cleaning it up, all the concerns of an old person." “I knew quite a lot about old people,” Paul continues, "I was a Boy Scout and I often visted local pensioners as a good deed. I used to think it was the right thing to do – I still do, actually – but what I’m saying is, I wasn’t ashamed to go round and ask someone if they wanted me to go the doctor’s for them or to help old ladies across the road. It had been instilled into me that that was a good deed. So I sat with lots of old ladies who chatted about the war and all this stuff, and also, as I fancied myself as a writer, a part of me was getting material. There was a corner of my brain that used to enjoy that kind of thing, building a repertoire of people and thoughts. Obviously writers are always attracted to detail: the lonely old person opening her can of cat food and eating it herself, the smell of the cat food, the mess in her room, her worrying always about cleaning it up, all the concerns of an old person."

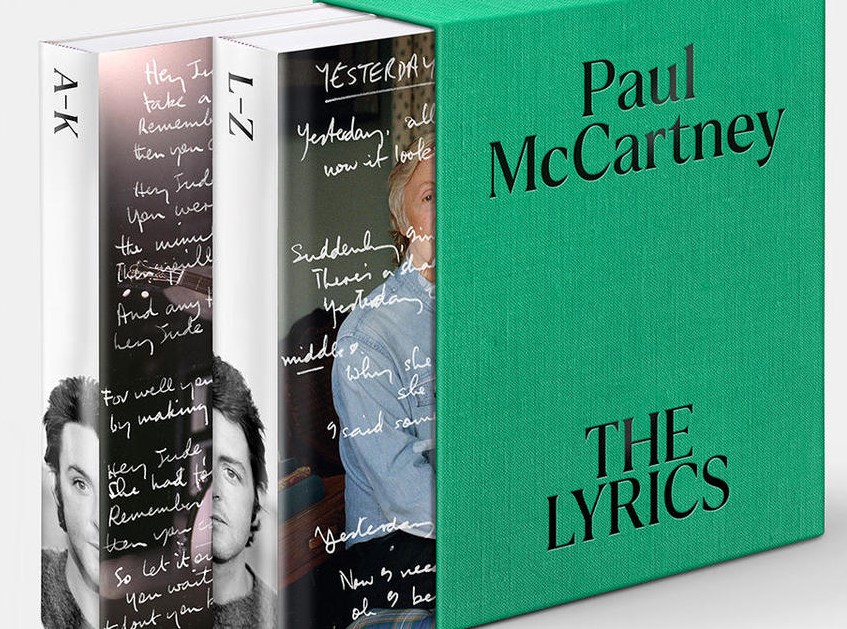

In his 2021 book "The Lyrics," Paul elaborates. "Growing up I knew a lot of old ladies - partly through what was called Bob-a-Job Week, when (Boy) Scouts did chores for a shilling. You'd get a shilling for cleaning out a shed or mowing a lawn. I wanted to write a song that would sum them up. Eleanor Rigby is based on an old lady that I got on with very well. I don't even know how I first met 'Eleanor Rigby,' but I would go around to her house, and not just once or twice. I found out that she lived on her own, so I would go around there and just chat, which is sort of crazy if you think about me being some young Liverpool guy. Later, I would offer to go and get her shopping. She'd give me a list and I'd bring the stuff back, and we'd sit in her kitchen. I still vividly remember the kitchen because she had a little crystal radio set...So I would visit, and just hearing her stories enriched my soul and influencd the songs I would later write." In his 2021 book "The Lyrics," Paul elaborates. "Growing up I knew a lot of old ladies - partly through what was called Bob-a-Job Week, when (Boy) Scouts did chores for a shilling. You'd get a shilling for cleaning out a shed or mowing a lawn. I wanted to write a song that would sum them up. Eleanor Rigby is based on an old lady that I got on with very well. I don't even know how I first met 'Eleanor Rigby,' but I would go around to her house, and not just once or twice. I found out that she lived on her own, so I would go around there and just chat, which is sort of crazy if you think about me being some young Liverpool guy. Later, I would offer to go and get her shopping. She'd give me a list and I'd bring the stuff back, and we'd sit in her kitchen. I still vividly remember the kitchen because she had a little crystal radio set...So I would visit, and just hearing her stories enriched my soul and influencd the songs I would later write."

In regards to the melody line chosen, Paul attempts to explain this as well. “I can hear a whole song in one chord. In fact, I think you can hear a whole song in one note, if you listen hard enough. But nobody ever listens hard enough. OK, so that’s the Joan of Arc bit…I wrote it at the piano, just vamping an E-major chord: letting that stay as a vamp and putting a melody over it, just danced over the top of it. It has almost Asian Indian rhythms…I couldn’t think of much more, so I put it away for a day.” In regards to the melody line chosen, Paul attempts to explain this as well. “I can hear a whole song in one chord. In fact, I think you can hear a whole song in one note, if you listen hard enough. But nobody ever listens hard enough. OK, so that’s the Joan of Arc bit…I wrote it at the piano, just vamping an E-major chord: letting that stay as a vamp and putting a melody over it, just danced over the top of it. It has almost Asian Indian rhythms…I couldn’t think of much more, so I put it away for a day.”

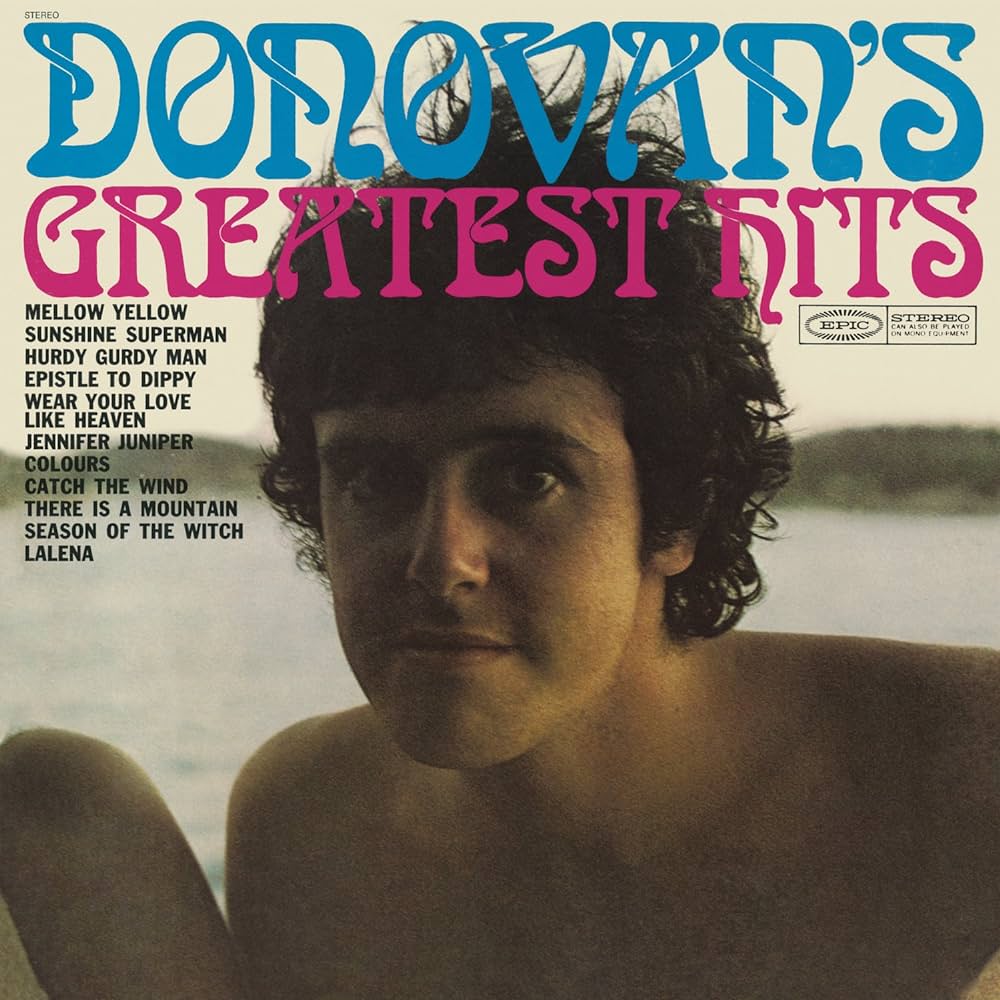

Even though it was just a sketch of a song at that point, McCartney not even liking the name Daisy Hawkins, he had enough of a framework written to play it to others, singer and friend Donovan Leitch being one of them. Since he lived nearby in Maida Vale, Paul dropped by and premiered the song for him. “One day I was on my own in the pad running through a few tunes on my Uher tape recorder,” Donovan recalls. "The doorbell rang. It was Paul on his own. We jammed a bit. He played me a tune about a strange chap…the protagonist…called ‘Ola Na Tungee,’ ‘Ola Na Tungee / Blowing his mind in the dark / with a pipe full of clay / no-one can say’…The words hadn’t yet come out right for him." Even though it was just a sketch of a song at that point, McCartney not even liking the name Daisy Hawkins, he had enough of a framework written to play it to others, singer and friend Donovan Leitch being one of them. Since he lived nearby in Maida Vale, Paul dropped by and premiered the song for him. “One day I was on my own in the pad running through a few tunes on my Uher tape recorder,” Donovan recalls. "The doorbell rang. It was Paul on his own. We jammed a bit. He played me a tune about a strange chap…the protagonist…called ‘Ola Na Tungee,’ ‘Ola Na Tungee / Blowing his mind in the dark / with a pipe full of clay / no-one can say’…The words hadn’t yet come out right for him."

As a sidenote to the events of this day at Donovan Leitch's house, McCartney nearly escaped being arrested by the police. As detailed in author Craig Brown's book "150 Glimpses Of The Beatles," Paul had parked his car illegally right in front of Donovan's house, protruding out of the designated spot with the doors open and the radio blaring. Donovan answered the door when the policeman knocked, and when Paul appeared at the door when it was determined it was his vehicle, the cop stated, "Oh, it's you, Mr. McCartney. Is this your car, a sports car?" He proceeded to ask Paul for the keys so as to park it in a proper parking spot himself and then returned his keys and went on his way. Little did he know that the policeman could have busted them for marijuana possession and being under its influence at the time, let alone for a parking violation. After this interuption, Paul and Donovan went back to working on this early version of "Eleanor Rigby." As a sidenote to the events of this day at Donovan Leitch's house, McCartney nearly escaped being arrested by the police. As detailed in author Craig Brown's book "150 Glimpses Of The Beatles," Paul had parked his car illegally right in front of Donovan's house, protruding out of the designated spot with the doors open and the radio blaring. Donovan answered the door when the policeman knocked, and when Paul appeared at the door when it was determined it was his vehicle, the cop stated, "Oh, it's you, Mr. McCartney. Is this your car, a sports car?" He proceeded to ask Paul for the keys so as to park it in a proper parking spot himself and then returned his keys and went on his way. Little did he know that the policeman could have busted them for marijuana possession and being under its influence at the time, let alone for a parking violation. After this interuption, Paul and Donovan went back to working on this early version of "Eleanor Rigby."

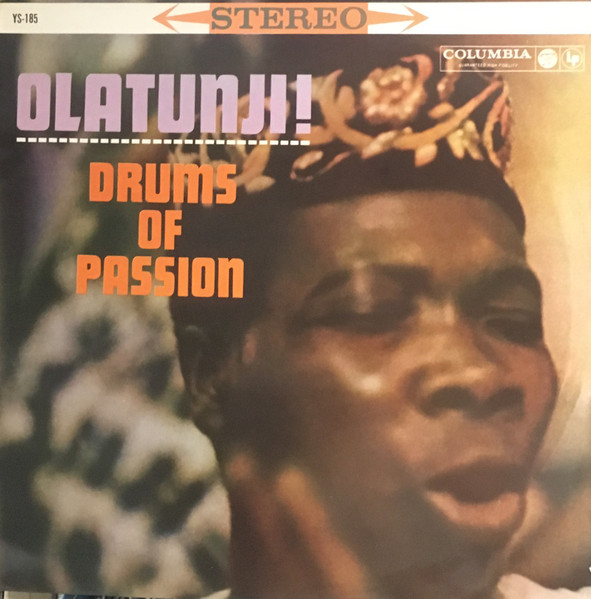

It appears that, if only subconsciously, Paul's use of the name 'Ola Na Tungee' to parse out the melody for "Eleanor Rigby" was inspired by Michael Babatunde Olatunji, a Nigerian composer and political activist whose influencial 1960 LP "Drums Of Passion" caught the attention of both manager Brian Epstein and New York disc jockey Murray the K. It's quite likely that, through either Brian Epstein or Murray the K, Paul became familiar with Michael Olatunji and considered incorporating a phonetic alteration of his last name in what eventually became "Eleanor Rigby." It appears that, if only subconsciously, Paul's use of the name 'Ola Na Tungee' to parse out the melody for "Eleanor Rigby" was inspired by Michael Babatunde Olatunji, a Nigerian composer and political activist whose influencial 1960 LP "Drums Of Passion" caught the attention of both manager Brian Epstein and New York disc jockey Murray the K. It's quite likely that, through either Brian Epstein or Murray the K, Paul became familiar with Michael Olatunji and considered incorporating a phonetic alteration of his last name in what eventually became "Eleanor Rigby."

Another individual that Paul played this preliminary song to was a professional music teacher. He relates, “When I’d written ‘Eleanor Rigby,’ I tried learning with a proper bloke from the Guildhall School of Music, whom I was put on to by Jane Asher’s mum (Margaret Eliot, an oboe teacher). But I didn’t get on with him either. I went off him when I showed him ‘Eleanor Rigby’ because I thought he would be interested, and he wasn’t. I thought that he would be intrigued by the little time jumps.” Another individual that Paul played this preliminary song to was a professional music teacher. He relates, “When I’d written ‘Eleanor Rigby,’ I tried learning with a proper bloke from the Guildhall School of Music, whom I was put on to by Jane Asher’s mum (Margaret Eliot, an oboe teacher). But I didn’t get on with him either. I went off him when I showed him ‘Eleanor Rigby’ because I thought he would be interested, and he wasn’t. I thought that he would be intrigued by the little time jumps.”

According to an official London tour guide and author Richard Porter, Paul continued working on the song at 34 Montagu Square, London, a residence owned by Ringo where McCartney had installed a studio in the basement. In Paul's book "The Lyrics," he remembers that an "early admirer of the song was William S. Burroughs who, of course, ended up on the cover of 'Sgt. Pepper.' He and I had met through the author Barry Miles and the Indica Bookshop, and he actually got to see the song take shape when I sometimes used the spoken-word studio that we had set up in the basement of Ringo's flat in Montagu Square." Regarding the name of the main character, Paul relates: “But I wasn’t comfortable with the name Miss Hawkins. I didn’t think it sounded real enough. I knew I could do better then...I wanted a really nice name that didn’t sound wrong. It had to sound like someone’s name, but different enough and wasn’t just Valerie Higgins, you know. It had to be a little more evocative...I’m always keen to get a name that sounds right. Looking at my old school photographs I remembered the names, and they all work: James Stringfellow, Grace Pendleton. Whereas when you read novels, it’s all ‘James Turnbury’ and it’s not real. So I was very keen to get a real-sounding name for that tune and the whole idea.” According to an official London tour guide and author Richard Porter, Paul continued working on the song at 34 Montagu Square, London, a residence owned by Ringo where McCartney had installed a studio in the basement. In Paul's book "The Lyrics," he remembers that an "early admirer of the song was William S. Burroughs who, of course, ended up on the cover of 'Sgt. Pepper.' He and I had met through the author Barry Miles and the Indica Bookshop, and he actually got to see the song take shape when I sometimes used the spoken-word studio that we had set up in the basement of Ringo's flat in Montagu Square." Regarding the name of the main character, Paul relates: “But I wasn’t comfortable with the name Miss Hawkins. I didn’t think it sounded real enough. I knew I could do better then...I wanted a really nice name that didn’t sound wrong. It had to sound like someone’s name, but different enough and wasn’t just Valerie Higgins, you know. It had to be a little more evocative...I’m always keen to get a name that sounds right. Looking at my old school photographs I remembered the names, and they all work: James Stringfellow, Grace Pendleton. Whereas when you read novels, it’s all ‘James Turnbury’ and it’s not real. So I was very keen to get a real-sounding name for that tune and the whole idea.”

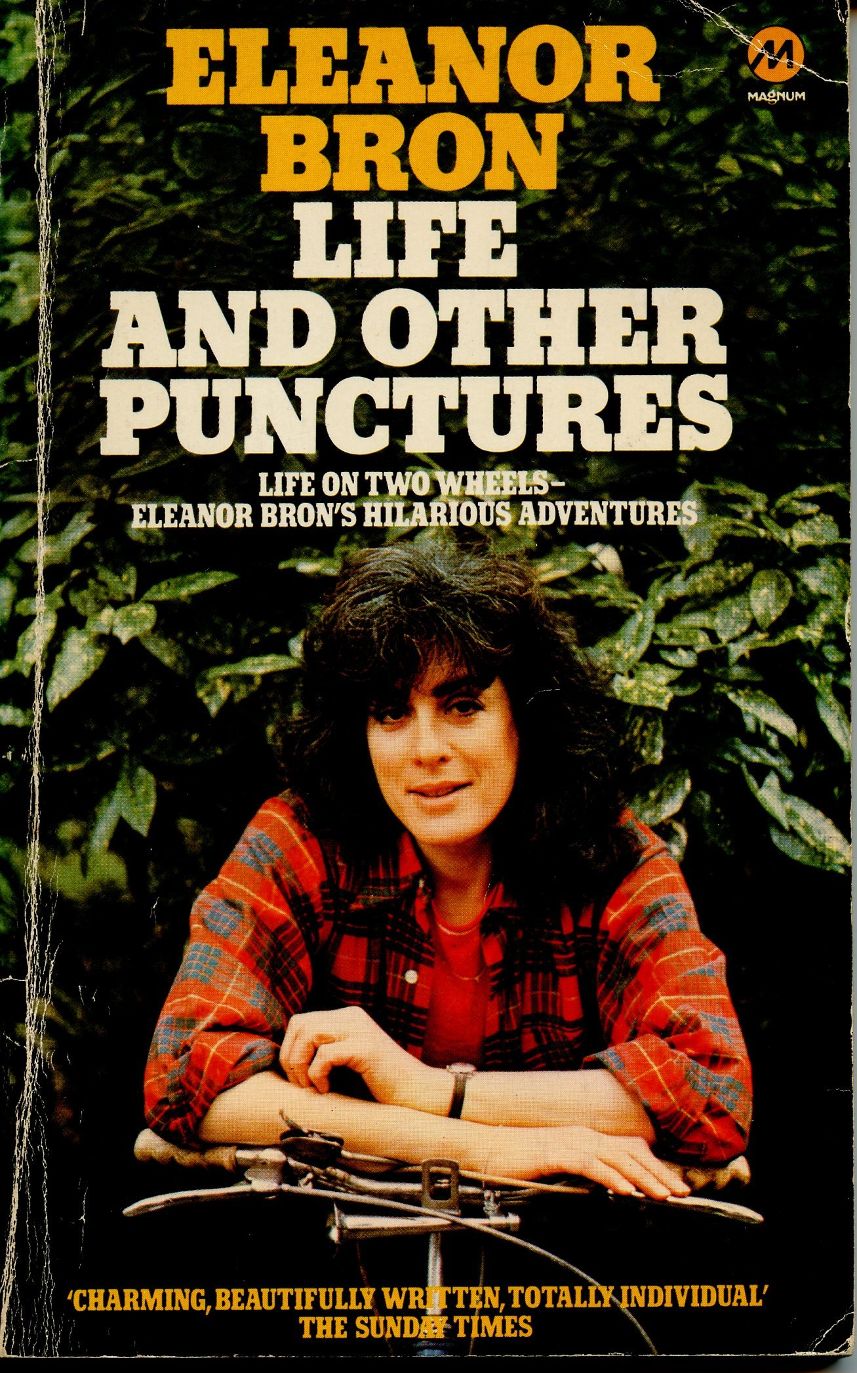

This is where the song's history begins to fragment. Regarding the character’s first name, Paul remembers, “We were working with Eleanor Bron on ‘Help!’ and I liked the name Eleanor…I’d seen her at Peter Cook’s Establishment Club in Greek Street, then she came on the film ‘Help!’ so we knew her quite well, John had a fling with her…it was the first time I’d ever been involved with that name.” This is where the song's history begins to fragment. Regarding the character’s first name, Paul remembers, “We were working with Eleanor Bron on ‘Help!’ and I liked the name Eleanor…I’d seen her at Peter Cook’s Establishment Club in Greek Street, then she came on the film ‘Help!’ so we knew her quite well, John had a fling with her…it was the first time I’d ever been involved with that name.”

That may sound convincing enough, but it doesn’t settle the matter. Enter songwriter and friend Lionel Bart (famous for the musical “Oliver”) who recollects things differently. “Paul has always thought that he came up with the name Eleanor because of having worked with Eleanor Bron in the film ‘Help!’ but I am convinced that he took the name from a gravestone in a cemetery close to Wimbledon Common where we were both walking. The name on this gravestone was Eleanor Bygraves and Paul thought the name fitted the song. He then came back to my office and began playing it on my clavichord.” That may sound convincing enough, but it doesn’t settle the matter. Enter songwriter and friend Lionel Bart (famous for the musical “Oliver”) who recollects things differently. “Paul has always thought that he came up with the name Eleanor because of having worked with Eleanor Bron in the film ‘Help!’ but I am convinced that he took the name from a gravestone in a cemetery close to Wimbledon Common where we were both walking. The name on this gravestone was Eleanor Bygraves and Paul thought the name fitted the song. He then came back to my office and began playing it on my clavichord.”

As for the last name, Paul explains, "I saw ‘Rigby’ on a shop in Bristol when I was walking around the city one evening…I remember quite distinctly having the name Eleanor, looking around for a believable surname and then wandering around the docklands in Bristol and seeing the shop there…I was in Bristol on a visit to see Jane Asher at the Old Vic (January 1966), and just walking around the dock area I saw an old shop called Rigby (actually ‘Rigby & Evens Ltd, Wine & Spirits Shippers” just across the street from the The Theatre Royale where Jane was starring in the play “The Happiest Days Of Your Life”) and I thought, oooh, It’s a very ordinary name and yet it’s a special name, it was exactly what I wanted. So Eleanor Rigby. I felt great. I’d got it! I pieced all the ideas together, got the melody and the chords." As for the last name, Paul explains, "I saw ‘Rigby’ on a shop in Bristol when I was walking around the city one evening…I remember quite distinctly having the name Eleanor, looking around for a believable surname and then wandering around the docklands in Bristol and seeing the shop there…I was in Bristol on a visit to see Jane Asher at the Old Vic (January 1966), and just walking around the dock area I saw an old shop called Rigby (actually ‘Rigby & Evens Ltd, Wine & Spirits Shippers” just across the street from the The Theatre Royale where Jane was starring in the play “The Happiest Days Of Your Life”) and I thought, oooh, It’s a very ordinary name and yet it’s a special name, it was exactly what I wanted. So Eleanor Rigby. I felt great. I’d got it! I pieced all the ideas together, got the melody and the chords."

"My mum's favorite cold cream was Nivea," Paul explains in his book "The Lyrics," "and I love it to this day. That's the cold cream I was thinking of in the description of the face Eleanor keeps 'in a jar by the door.' I was always a little scared by how often women used cold cream."

.jpg) Now for a serendipitous twist. Paul admits: “It seems that up in Woolton Cemetery, where I used to hang out a lot with John, there’s a gravestone to an Eleanor Rigby.” Sometime in the '80s this gravestone was discovered in the Woolton, Liverpool graveyard of St. Peter’s Parish Church, just a few yards away from where John and Paul had met for the first time in 1957. Now for a serendipitous twist. Paul admits: “It seems that up in Woolton Cemetery, where I used to hang out a lot with John, there’s a gravestone to an Eleanor Rigby.” Sometime in the '80s this gravestone was discovered in the Woolton, Liverpool graveyard of St. Peter’s Parish Church, just a few yards away from where John and Paul had met for the first time in 1957.

“It was either complete coincidence or in my subconscious,” McCartney continues. "I suppose it was more likely in my subconscious, because I will have been amongst those graves knocking around with John and wandering through there. It was the sort of place we used to sunbathe, and we probably had a crafty fag in the graveyard…but there could be 3000 gravestones in Britain with Eleanor Rigby on. It is possible that I saw it and subconsciously remembered it," Paul admits. "So subconscious it may be – but this is just bigger than me. I don’t know the answer to that one. Coincidence is just a word that says two things coincided. We rely on it as an explanation, but it actually just names it – it goes no further than that. But as to why they happen together, there are probably far deeper reasons that our little brains can't grasp." “It was either complete coincidence or in my subconscious,” McCartney continues. "I suppose it was more likely in my subconscious, because I will have been amongst those graves knocking around with John and wandering through there. It was the sort of place we used to sunbathe, and we probably had a crafty fag in the graveyard…but there could be 3000 gravestones in Britain with Eleanor Rigby on. It is possible that I saw it and subconsciously remembered it," Paul admits. "So subconscious it may be – but this is just bigger than me. I don’t know the answer to that one. Coincidence is just a word that says two things coincided. We rely on it as an explanation, but it actually just names it – it goes no further than that. But as to why they happen together, there are probably far deeper reasons that our little brains can't grasp."

And now the question of what, if any, role did John Lennon play in writing the song. In varied interviews, he would have us think he played a vital role. When asked by Hit Parader magazine in 1972 about the song, his answer was “Both of us. I wrote a good lot of the lyrics, about 70 per cent.” In 1980 he related: “’Eleanor Rigby’ was Paul’s baby, and I helped with the education of the child.” And now the question of what, if any, role did John Lennon play in writing the song. In varied interviews, he would have us think he played a vital role. When asked by Hit Parader magazine in 1972 about the song, his answer was “Both of us. I wrote a good lot of the lyrics, about 70 per cent.” In 1980 he related: “’Eleanor Rigby’ was Paul’s baby, and I helped with the education of the child.”

His long dissertation to Playboy magazine in 1980 about the song paints a very vivid picture. “Paul’s first verse, and the rest of the verses are basically mine. Paul had the theme, the whole bit about Eleanor Rigby in the church where a wedding had been. He knew he had this song and he needed help…part of it we worked out together: Paul didn’t have the middle – ‘ahh, look at all the lonely people.’ He and George and I were sort of sitting around the room throwing things around and I left to go to the toilet. I heard someone say that line and I turned around and said, ‘That’s it!’” What John was here describing was a writing session that Paul also described by saying “Then I took it down to John’s house in Weybridge. We sat around, laughing, got stoned and finished it off. It all sort of flowed from there.” His long dissertation to Playboy magazine in 1980 about the song paints a very vivid picture. “Paul’s first verse, and the rest of the verses are basically mine. Paul had the theme, the whole bit about Eleanor Rigby in the church where a wedding had been. He knew he had this song and he needed help…part of it we worked out together: Paul didn’t have the middle – ‘ahh, look at all the lonely people.’ He and George and I were sort of sitting around the room throwing things around and I left to go to the toilet. I heard someone say that line and I turned around and said, ‘That’s it!’” What John was here describing was a writing session that Paul also described by saying “Then I took it down to John’s house in Weybridge. We sat around, laughing, got stoned and finished it off. It all sort of flowed from there.”

Good friend Pete Shotton, who was present on that day, recalls the details: “Most of the song was written in John’s music room at his house in Kenwood, during one of my weekend visits. The other three Beatles and their wives had come over for dinner, and after which, we all gathered around the television in Cyn’s beloved library. This particular night, John grew bored with the TV program…He said, ‘Let’s go upstairs and play a bit of music.’ Paul, George and Ringo duly followed John upstairs to a room adjoining his little recording studio. Paul, as always, had brought along his guitar, which he got out and began strumming. ‘I’ve got this little tune here,’ he said. ‘It keeps popping into me head, but I haven’t got very far with it.’ Then he sang the beginning of ‘Eleanor Rigby.’ We all sat around, making suggestions, throwing out the odd line or phrase, all of us, that is, except for the Beatle who had proposed the session in the first place. Good friend Pete Shotton, who was present on that day, recalls the details: “Most of the song was written in John’s music room at his house in Kenwood, during one of my weekend visits. The other three Beatles and their wives had come over for dinner, and after which, we all gathered around the television in Cyn’s beloved library. This particular night, John grew bored with the TV program…He said, ‘Let’s go upstairs and play a bit of music.’ Paul, George and Ringo duly followed John upstairs to a room adjoining his little recording studio. Paul, as always, had brought along his guitar, which he got out and began strumming. ‘I’ve got this little tune here,’ he said. ‘It keeps popping into me head, but I haven’t got very far with it.’ Then he sang the beginning of ‘Eleanor Rigby.’ We all sat around, making suggestions, throwing out the odd line or phrase, all of us, that is, except for the Beatle who had proposed the session in the first place.

Apparently before this songwriting session, Paul had the idea for a second character for the song – a priest. “I had Father McCartney as the priest,” McCartney explains, “just because I knew that was right for the syllables, but I knew I didn’t want it even though John liked it so we opened the telephone book, went to McCartney and looked what followed it, and shortly after, it was McKenzie. I thought, Oh, that’s good...John wanted it to stay McCartney, but I said, ‘No, it’s my dad! Father McCartney.’ He said, ‘It’s good, it works fine.’ I agreed it worked, but I didn’t want to sing that, it was too loaded, it asked too many questions. I wanted it to be anonymous. John helped me on a few words but I’d put it down 80-20 to me, something like that.” Apparently before this songwriting session, Paul had the idea for a second character for the song – a priest. “I had Father McCartney as the priest,” McCartney explains, “just because I knew that was right for the syllables, but I knew I didn’t want it even though John liked it so we opened the telephone book, went to McCartney and looked what followed it, and shortly after, it was McKenzie. I thought, Oh, that’s good...John wanted it to stay McCartney, but I said, ‘No, it’s my dad! Father McCartney.’ He said, ‘It’s good, it works fine.’ I agreed it worked, but I didn’t want to sing that, it was too loaded, it asked too many questions. I wanted it to be anonymous. John helped me on a few words but I’d put it down 80-20 to me, something like that.”

Pete Shotton adds a little more detail to the McCartney/McKenzie issue. “Then Paul got to the verse about the cleric, whose name he had down as Father McCartney. Ringo came up with the (lyric) about ‘Father McCartney darning his socks in the night,’ which everyone liked. ‘Hang on a minute, Paul,’ I said. ‘People are going to think that’s your poor old dad, left all alone in Liverpool to darn his own socks’…(Paul) laughs, ‘I never thought of that. We’d better change the name. What shall we call him then?’ I then noticed a telephone directory lying around, and said, ‘Give us that phone book. I’ll have a look through the Macs.’ One name that particularly amused us was McVicar, but it didn’t quite seem to flow with the line when Paul sang it. So I asked him to try Father McKenzie out for size, and everyone appeared to like the lilt of it." Interestingly, Beatles historian and author Robert Rodriguez, upon studying the original scribbled lyric sheet, identifies George Harrison as the writer of the song's key lyric "ah, look at all the lonely people.” Pete Shotton adds a little more detail to the McCartney/McKenzie issue. “Then Paul got to the verse about the cleric, whose name he had down as Father McCartney. Ringo came up with the (lyric) about ‘Father McCartney darning his socks in the night,’ which everyone liked. ‘Hang on a minute, Paul,’ I said. ‘People are going to think that’s your poor old dad, left all alone in Liverpool to darn his own socks’…(Paul) laughs, ‘I never thought of that. We’d better change the name. What shall we call him then?’ I then noticed a telephone directory lying around, and said, ‘Give us that phone book. I’ll have a look through the Macs.’ One name that particularly amused us was McVicar, but it didn’t quite seem to flow with the line when Paul sang it. So I asked him to try Father McKenzie out for size, and everyone appeared to like the lilt of it." Interestingly, Beatles historian and author Robert Rodriguez, upon studying the original scribbled lyric sheet, identifies George Harrison as the writer of the song's key lyric "ah, look at all the lonely people.”

But could there have been an actual Father McKenzie? “It wasn’t written about anyone,” Paul insists. “A man appeared, who died a few years ago, who said, ‘I’m Father McKenzie.’ Anyone who was called Father McKenzie and had any slim contact with The Beatles quite naturally would think, ‘Well, I spoke to Paul and he might easily have written that about me,’ or he may have spoken to John and thought John thought it up.” But could there have been an actual Father McKenzie? “It wasn’t written about anyone,” Paul insists. “A man appeared, who died a few years ago, who said, ‘I’m Father McKenzie.’ Anyone who was called Father McKenzie and had any slim contact with The Beatles quite naturally would think, ‘Well, I spoke to Paul and he might easily have written that about me,’ or he may have spoken to John and thought John thought it up.”

Another concern was the lyrical content of the final verse. Pete Shotton continues: “After we tinkered with a few more phrases, Paul said, ‘The real trouble is I’ve no idea how to finish this song.’ I said, ‘Why don’t you have Eleanor Rigby dying and have Father McKenzie doing the burial service for her? That way you’d have the two lonely people coming together in the end, but too late.’ John then piped in with his first comment of the entire session, ‘I don’t think you understand what we’re trying to get at, Pete.’ All I could think of to say was, ‘F**k you, John.’ Paul packed his guitar away, and we all wandered out of the room. Even after George produced a joint to lighten up the mood, I continued to feel more than a bit uptight about John’s unwarranted sarcasm. Maybe my great suggestion hadn’t been so great after all…Though John was to take credit in one of his last interviews, for most of the lyrics, my own recollection is that ‘Eleanor Rigby’ was one ‘Lennon / McCartney’ classic in which John’s composition was virtually nil.” Another concern was the lyrical content of the final verse. Pete Shotton continues: “After we tinkered with a few more phrases, Paul said, ‘The real trouble is I’ve no idea how to finish this song.’ I said, ‘Why don’t you have Eleanor Rigby dying and have Father McKenzie doing the burial service for her? That way you’d have the two lonely people coming together in the end, but too late.’ John then piped in with his first comment of the entire session, ‘I don’t think you understand what we’re trying to get at, Pete.’ All I could think of to say was, ‘F**k you, John.’ Paul packed his guitar away, and we all wandered out of the room. Even after George produced a joint to lighten up the mood, I continued to feel more than a bit uptight about John’s unwarranted sarcasm. Maybe my great suggestion hadn’t been so great after all…Though John was to take credit in one of his last interviews, for most of the lyrics, my own recollection is that ‘Eleanor Rigby’ was one ‘Lennon / McCartney’ classic in which John’s composition was virtually nil.”

It appears by the above account that the writing of the song was complete here at John’s Kenwood home. However, one further account, that of John, appears to indicate that more writing needed to be done while in the recording studio. In his Playboy interview of 1980, he includes this interesting interchange: It appears by the above account that the writing of the song was complete here at John’s Kenwood home. However, one further account, that of John, appears to indicate that more writing needed to be done while in the recording studio. In his Playboy interview of 1980, he includes this interesting interchange:

“Rather than ask me to do the lyrics, he said, ‘Hey, you guys, finish up the lyrics,’ while he sort of fiddled around with the track or the arranging or something at another part of the giant studio at EMI. I sat there with Mal Evans, a road manager who was a telephone installer, and Neil Aspinall, a student accountant who became a road manager, and it was the three of us he was talking to. I was insulted and hurt that he had thrown it out in the air that way. Actually, he meant for me to do it, but he wouldn’t ask…and, of course, there isn’t a line of theirs in the song, because I finally went off to a room with Paul and we finished the song…That was the kind of insensitivity he had, which made me upset in the later years. It’s just the kind of person he is. It meant nothing to him. I wanted to grab a piece of the song, so I wrote it with them sitting at that table, thinking, ‘How dare he throw it out in the air like that?'" “Rather than ask me to do the lyrics, he said, ‘Hey, you guys, finish up the lyrics,’ while he sort of fiddled around with the track or the arranging or something at another part of the giant studio at EMI. I sat there with Mal Evans, a road manager who was a telephone installer, and Neil Aspinall, a student accountant who became a road manager, and it was the three of us he was talking to. I was insulted and hurt that he had thrown it out in the air that way. Actually, he meant for me to do it, but he wouldn’t ask…and, of course, there isn’t a line of theirs in the song, because I finally went off to a room with Paul and we finished the song…That was the kind of insensitivity he had, which made me upset in the later years. It’s just the kind of person he is. It meant nothing to him. I wanted to grab a piece of the song, so I wrote it with them sitting at that table, thinking, ‘How dare he throw it out in the air like that?'"

To corroborate that last minute lyric writing was done on "Eleanor Rigby" in the recording studio, producer George Martin was asked by Hit Parader magazine in 1971 if he could clear up the discrepancies about the writing of the song. “I had assumed that it was all Paul,” he replied, adding “in fact I do remember, actually at the recording, Paul was missing a few lyrics and wanting them, and going round and asking people, ‘What can we put in here?’ and Neil (Aspinal) and Mal (Evans) and I were coming up with suggestions…pretty petty, really. Everyone contributed things occasionally.” Interestingly, we can easily notice the suspicious omission of Lennon’s name in his recollection. To corroborate that last minute lyric writing was done on "Eleanor Rigby" in the recording studio, producer George Martin was asked by Hit Parader magazine in 1971 if he could clear up the discrepancies about the writing of the song. “I had assumed that it was all Paul,” he replied, adding “in fact I do remember, actually at the recording, Paul was missing a few lyrics and wanting them, and going round and asking people, ‘What can we put in here?’ and Neil (Aspinal) and Mal (Evans) and I were coming up with suggestions…pretty petty, really. Everyone contributed things occasionally.” Interestingly, we can easily notice the suspicious omission of Lennon’s name in his recollection.

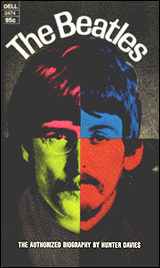

Another interesting quote is from a personal discussion Paul had with The Beatles’ official biographer Hunter Davies as printed in the 1985 edition of his book “The Beatles: The Authorized Biography.” Paul states: “I saw somewhere that he (John) says he helped on ‘Eleanor Rigby.’ Yeah, about half a line!” Paul’s book “Many Years From Now” may contain the definitive explanation, Barry Miles stating: “It seems as though John backed himself into a corner and couldn’t find a way to save face, because a less likely John Lennon composition would be hard to find.” Another interesting quote is from a personal discussion Paul had with The Beatles’ official biographer Hunter Davies as printed in the 1985 edition of his book “The Beatles: The Authorized Biography.” Paul states: “I saw somewhere that he (John) says he helped on ‘Eleanor Rigby.’ Yeah, about half a line!” Paul’s book “Many Years From Now” may contain the definitive explanation, Barry Miles stating: “It seems as though John backed himself into a corner and couldn’t find a way to save face, because a less likely John Lennon composition would be hard to find.”

Therefore, my dear Beatles fans, it’s up to you to be the judge.

Recording History

The recording history of “Eleanor Rigby” has to begin with the various demo recordings Paul personally made at his recording studio in Marylebone. American novelist William Burroughs, as explained in “Many Years From Now,” was “one of the people who heard the song in all its different stages.” “I saw him there many times,” William Burroughs recalls, “He’d just come in and work on his ‘Eleanor Rigby’…so I saw the song taking shape…I could see he knew what he was doing.” The recording history of “Eleanor Rigby” has to begin with the various demo recordings Paul personally made at his recording studio in Marylebone. American novelist William Burroughs, as explained in “Many Years From Now,” was “one of the people who heard the song in all its different stages.” “I saw him there many times,” William Burroughs recalls, “He’d just come in and work on his ‘Eleanor Rigby’…so I saw the song taking shape…I could see he knew what he was doing.”

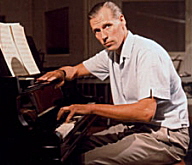

Before proper recording of the song began at EMI Studios, however, a decision needed to be made as to its arrangement. As related by engineer Geoff Emerick in his 2006 book “Here, There And Everywhere,” the song was personally debuted to George Martin by Paul at an undisclosed date in the studio. “After hearing Paul play this beautiful song on acoustic guitar, George Martin felt that the only accompaniment that was necessary was that of a double string quartet: four violins, two violas, and two cellos. Paul wasn’t immediately enamored of the concept – he was afraid of it sounding too cloying, too “Mancini” – but George eventually talked him into it, assuring him he would write a string arrangement that would be suitable. 'Okay, but I want the strings to sound really biting,' Paul warned as he signed off on the idea.” Before proper recording of the song began at EMI Studios, however, a decision needed to be made as to its arrangement. As related by engineer Geoff Emerick in his 2006 book “Here, There And Everywhere,” the song was personally debuted to George Martin by Paul at an undisclosed date in the studio. “After hearing Paul play this beautiful song on acoustic guitar, George Martin felt that the only accompaniment that was necessary was that of a double string quartet: four violins, two violas, and two cellos. Paul wasn’t immediately enamored of the concept – he was afraid of it sounding too cloying, too “Mancini” – but George eventually talked him into it, assuring him he would write a string arrangement that would be suitable. 'Okay, but I want the strings to sound really biting,' Paul warned as he signed off on the idea.”

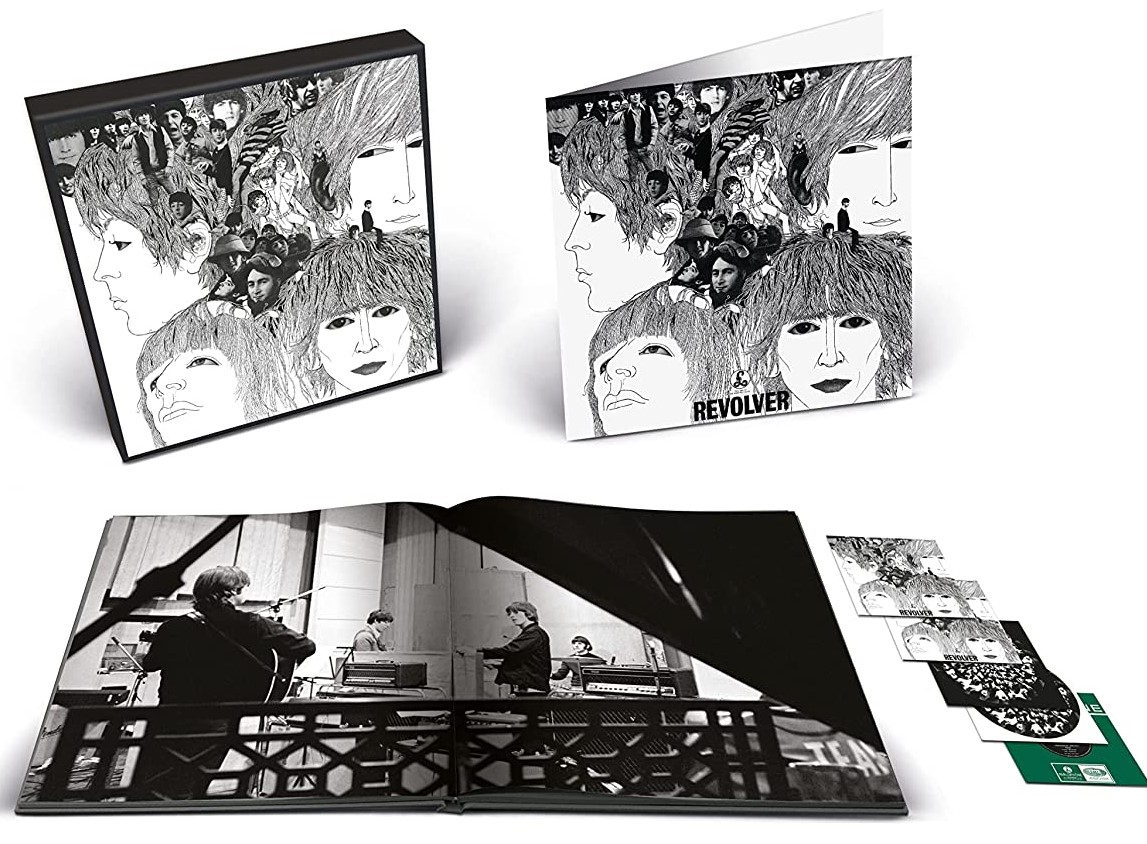

To throw another monkey wrench into the story, both John and Paul are on record as saying that it was Paul’s original concept to use strings on the song. “The violin backing was Paul’s idea,” John insists, “Jane Asher had turned him on to Vivaldi and it was very good. The violins were straight out of Vivaldi. I can’t take any credit for that, at all.” As acknowedged in the book accompanying the 2022 Deluxe editions of "Revolver," "The rhythmic drive of 'Eleanor Rigby' is reminiscent of 'Winter: 1. Allegro non molto' from Vivaldi's 'Four Seasons.'" Paul humbly states: “I thought of the backing but it was George Martin who finished it off. I just go bash, bash on the piano. He knows what I mean.” To throw another monkey wrench into the story, both John and Paul are on record as saying that it was Paul’s original concept to use strings on the song. “The violin backing was Paul’s idea,” John insists, “Jane Asher had turned him on to Vivaldi and it was very good. The violins were straight out of Vivaldi. I can’t take any credit for that, at all.” As acknowedged in the book accompanying the 2022 Deluxe editions of "Revolver," "The rhythmic drive of 'Eleanor Rigby' is reminiscent of 'Winter: 1. Allegro non molto' from Vivaldi's 'Four Seasons.'" Paul humbly states: “I thought of the backing but it was George Martin who finished it off. I just go bash, bash on the piano. He knows what I mean.”

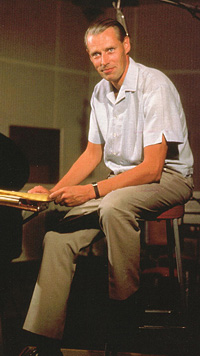

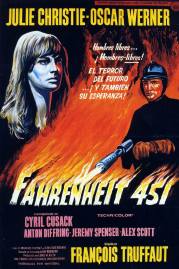

At any rate, shortly after George Martin was introduced to the song, he and Paul convened at Martin’s home to work out the arrangement, similarly to what they had done with the previous year's “Yesterday.” “Paul came round to my flat one day and he played the piano and I played the piano and I took a note of his music,” George Martin recalls, "I was very much inspired by Bernard Herrmann, in particular a (movie) score he did for the Truffaut film ‘Fahrenheit 451.’ That really impressed me, especially the strident string writing. When Paul told me he wanted the strings in ‘Eleanor Rigby’ to be doing a rhythm it was Herrmann’s score which was a particular influence." At any rate, shortly after George Martin was introduced to the song, he and Paul convened at Martin’s home to work out the arrangement, similarly to what they had done with the previous year's “Yesterday.” “Paul came round to my flat one day and he played the piano and I played the piano and I took a note of his music,” George Martin recalls, "I was very much inspired by Bernard Herrmann, in particular a (movie) score he did for the Truffaut film ‘Fahrenheit 451.’ That really impressed me, especially the strident string writing. When Paul told me he wanted the strings in ‘Eleanor Rigby’ to be doing a rhythm it was Herrmann’s score which was a particular influence."

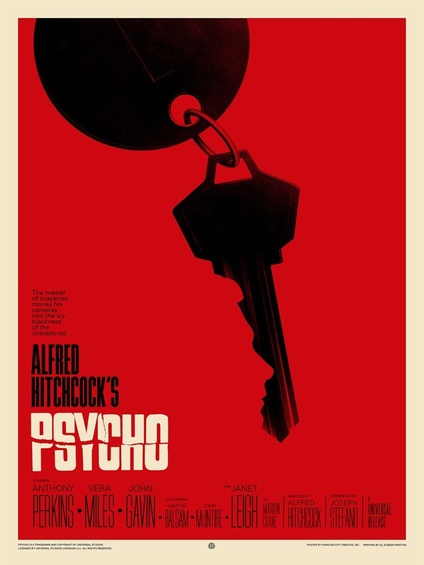

In his book "The Lyrics," McCartney elaborates further: "When I took the song to George (Martin), I said that, for accompaniment, I wanted a series of E minor chord stabs. In fact, the whole song is really only two chords: C major and E minor. In George's version of things, he conflates my idea of the stabs and his own inspiration by Bernard Herrmann, who had written the music for the movie 'Psycho.' George (Martin) wanted to bring some of that drama into the arrangement. And, of course, there's some kind of madcap connection between Eleanor Rigby, an elderly woman left high and dry, and the mummified mother in 'Psycho.'" George Martin adds, "I did notice in particular that the strings he wrote (for 'Psycho') were the very opposite of syrupy. They were jagged, spiky, very menacing. That kind of short attack that you get on his strings was very usueful on 'Eleanor Rigby.' It had to be very marcato; it had to be an absolutely tight rhythm, which strings aren't noted for." In his book "The Lyrics," McCartney elaborates further: "When I took the song to George (Martin), I said that, for accompaniment, I wanted a series of E minor chord stabs. In fact, the whole song is really only two chords: C major and E minor. In George's version of things, he conflates my idea of the stabs and his own inspiration by Bernard Herrmann, who had written the music for the movie 'Psycho.' George (Martin) wanted to bring some of that drama into the arrangement. And, of course, there's some kind of madcap connection between Eleanor Rigby, an elderly woman left high and dry, and the mummified mother in 'Psycho.'" George Martin adds, "I did notice in particular that the strings he wrote (for 'Psycho') were the very opposite of syrupy. They were jagged, spiky, very menacing. That kind of short attack that you get on his strings was very usueful on 'Eleanor Rigby.' It had to be very marcato; it had to be an absolutely tight rhythm, which strings aren't noted for."

In Paul's 2021 Hulu series "McCartney 3,2,1," he remembers the events of his introducing the song to his producer. "I remember showing this to George Martin. We'd already done 'Yesterday,' so this was like, 'I think this song can suit (strings).' But instead of a quartet, it was now (expanded to) an octet just to do something a bit different. And I brought it in like...(demonstrates on piano)...and then George would show me. He said, 'Well, ok, that's sort of rock 'n' roll, it's all pretty much in one octave.' He would then say, 'Ok, so the cello would go there and then the viola would go there and then...' So he would seperate all of the notes and that's the fabulous orchestration that he did." Regarding the absence of piano on the recording, Paul continued: "That was the thing because, y'know, 'Yesterday' had just been the one guitar, so we decided we'd kind of try and go a little bit further and just have this and then I would sing to this, y'know. So I'd showed George (Martin) the chords, he would then transpose it." In Paul's 2021 Hulu series "McCartney 3,2,1," he remembers the events of his introducing the song to his producer. "I remember showing this to George Martin. We'd already done 'Yesterday,' so this was like, 'I think this song can suit (strings).' But instead of a quartet, it was now (expanded to) an octet just to do something a bit different. And I brought it in like...(demonstrates on piano)...and then George would show me. He said, 'Well, ok, that's sort of rock 'n' roll, it's all pretty much in one octave.' He would then say, 'Ok, so the cello would go there and then the viola would go there and then...' So he would seperate all of the notes and that's the fabulous orchestration that he did." Regarding the absence of piano on the recording, Paul continued: "That was the thing because, y'know, 'Yesterday' had just been the one guitar, so we decided we'd kind of try and go a little bit further and just have this and then I would sing to this, y'know. So I'd showed George (Martin) the chords, he would then transpose it."

With the arrangement then decided and a George Martin-written score completed, April 28th, 1966 was the date chosen to record the instrumentation for the song. The eight classical musicians that made up the “octet,” along with Paul, John and the EMI production team of George Martin, Geoff Emerick and Phil McDonald, entered EMI Studio Two at 5 pm for what only took a little less than three hours to perfect. Paul and John mostly stayed up in the control room while George Martin conducted the musicians in the studio. "George (Martin) would talk to the musicians," Paul explained in his "McCartney 3,2,1" Hulu series, describing the producer's instructions as "'dunk, dunk, dunk, I really want it bam, bam, bam, quite bright, staccato, chunk, chunk, chunk.' And they got into it. He loved it. It was a nice little arrangement on its own." With the arrangement then decided and a George Martin-written score completed, April 28th, 1966 was the date chosen to record the instrumentation for the song. The eight classical musicians that made up the “octet,” along with Paul, John and the EMI production team of George Martin, Geoff Emerick and Phil McDonald, entered EMI Studio Two at 5 pm for what only took a little less than three hours to perfect. Paul and John mostly stayed up in the control room while George Martin conducted the musicians in the studio. "George (Martin) would talk to the musicians," Paul explained in his "McCartney 3,2,1" Hulu series, describing the producer's instructions as "'dunk, dunk, dunk, I really want it bam, bam, bam, quite bright, staccato, chunk, chunk, chunk.' And they got into it. He loved it. It was a nice little arrangement on its own."

Following Paul’s instructions to have the strings sound “biting,” Geoff Emerick "took note of what he said and began thinking how to accomplish that…String quartets were traditionally recorded with just one or two microphones, placed high, several feet up in the air so that the sound of the bows scraping couldn’t be heard. But with McCartney’s directive in mind, I decided to close-mic the instruments, which was a new concept. The (string) musicians were horrified! One of them gave me a look of disdain, rolled his eyes to the ceiling, and said under his breath, ‘You can’t do that, you know.’ His words shook my confidence and made me start to second-guess myself. But I carried on regardless, determined to at least hear what it sounded like." Following Paul’s instructions to have the strings sound “biting,” Geoff Emerick "took note of what he said and began thinking how to accomplish that…String quartets were traditionally recorded with just one or two microphones, placed high, several feet up in the air so that the sound of the bows scraping couldn’t be heard. But with McCartney’s directive in mind, I decided to close-mic the instruments, which was a new concept. The (string) musicians were horrified! One of them gave me a look of disdain, rolled his eyes to the ceiling, and said under his breath, ‘You can’t do that, you know.’ His words shook my confidence and made me start to second-guess myself. But I carried on regardless, determined to at least hear what it sounded like."

"We did one take with the mics fairly close, then on the next take I decided to get extreme and move the mics in really close – perhaps just an inch or so away from each instrument. It was a fine line: I didn’t want to make the musicians so uncomfortable that they couldn’t give their best performance, but my job was to achieve what Paul wanted. That was the sound he liked, and so that was the miking we used, despite the string players’ unhappiness. To some degree, I could understand why they were so upset: they were scared of playing a bum note, and being under a microscope like that meant that any discrepancy in their playing was going to be magnified. Also, the technical limitations at the time were such that we couldn’t easily drop in, so they had to play the whole song correctly from beginning to end every time.” "We did one take with the mics fairly close, then on the next take I decided to get extreme and move the mics in really close – perhaps just an inch or so away from each instrument. It was a fine line: I didn’t want to make the musicians so uncomfortable that they couldn’t give their best performance, but my job was to achieve what Paul wanted. That was the sound he liked, and so that was the miking we used, despite the string players’ unhappiness. To some degree, I could understand why they were so upset: they were scared of playing a bum note, and being under a microscope like that meant that any discrepancy in their playing was going to be magnified. Also, the technical limitations at the time were such that we couldn’t easily drop in, so they had to play the whole song correctly from beginning to end every time.”

“Even without peering through the control room glass, I could hear the sound of the eight musicians sliding their chairs back before every take, so I had to keep going down there and moving the mics back in closer after every take: it was comic, really. Finally, George Martin told them pointedly to stop moving off mic.” “Even without peering through the control room glass, I could hear the sound of the eight musicians sliding their chairs back before every take, so I had to keep going down there and moving the mics back in closer after every take: it was comic, really. Finally, George Martin told them pointedly to stop moving off mic.”

Fourteen takes of the song were recorded (ten of them being complete), these being captured on two reels of four-track tape. Tracks one and two of the tape contained two violins each, while track three contained two cellos and track four contained two violas. In between takes one and two, a request came from McCartney, who was in the control room while George Martin was conducting the musicians in the studio. According to Mark Lewisohn’s account in “The Beatles Recording Sessions,” George Martin attempted to placate Paul's previous request for the musicians to play without vibrato as he formerly insisted for “Yesterday,” this resulting in what Mark Lewisohn describes as "an amusing incident. Fourteen takes of the song were recorded (ten of them being complete), these being captured on two reels of four-track tape. Tracks one and two of the tape contained two violins each, while track three contained two cellos and track four contained two violas. In between takes one and two, a request came from McCartney, who was in the control room while George Martin was conducting the musicians in the studio. According to Mark Lewisohn’s account in “The Beatles Recording Sessions,” George Martin attempted to placate Paul's previous request for the musicians to play without vibrato as he formerly insisted for “Yesterday,” this resulting in what Mark Lewisohn describes as "an amusing incident.

Between takes one and two, George Martin asked the players if they could play without vibrato. They tried two quick versions, one with, one without – not classified as takes – and at the end George Martin called up to Paul McCartney, ‘Can you hear the difference?’ – ‘Er…not much!’ Ironically, the musicians could and they favored playing without, which must have pleased Paul." This recoring, which was labeled 'Talking (Keep)" on the tape box, is included in the 2022 Deluxe editions of "Revolver." This recording also reveals that the musicians acknowledged that is was "very difficult not to play with vibrato" and grumble good-naturedly, "all those years of learning and he says it sounds the same!" George Martin thereafter requested them to "Keep the vibrato fairly narrow, not too wide a vibrato." Between takes one and two, George Martin asked the players if they could play without vibrato. They tried two quick versions, one with, one without – not classified as takes – and at the end George Martin called up to Paul McCartney, ‘Can you hear the difference?’ – ‘Er…not much!’ Ironically, the musicians could and they favored playing without, which must have pleased Paul." This recoring, which was labeled 'Talking (Keep)" on the tape box, is included in the 2022 Deluxe editions of "Revolver." This recording also reveals that the musicians acknowledged that is was "very difficult not to play with vibrato" and grumble good-naturedly, "all those years of learning and he says it sounds the same!" George Martin thereafter requested them to "Keep the vibrato fairly narrow, not too wide a vibrato."

"Take 14" was deemed the best, George Martin asking the musicians to "play with more sort of vigor and confidence" before "take five" and to play with more "short attack" as the recording session progressed (as witnessed on "take two" as later included in the Deluxe editions of "Revolver"). "Take 14" was then mixed down at the close of the session onto track one of another four-track tape, to allow three available open tracks for the vocal overdubs to be done at the next recording session. "Take 14" was deemed the best, George Martin asking the musicians to "play with more sort of vigor and confidence" before "take five" and to play with more "short attack" as the recording session progressed (as witnessed on "take two" as later included in the Deluxe editions of "Revolver"). "Take 14" was then mixed down at the close of the session onto track one of another four-track tape, to allow three available open tracks for the vocal overdubs to be done at the next recording session.

"I was very excited actually," Paul remembers in "McCartney 3,2,1" about his witnessing the performance of the octet. "Downstairs at Abbey Road, the eight guys assembled and they did it live...I would go down and say 'hi' and listen to it down there, which is always nice at first. They you go up and see what the engineers are making of it. Y'know, they'd put it all together, put the right little bits of fairy dust on it and they now made it like a record!". "I was very excited actually," Paul remembers in "McCartney 3,2,1" about his witnessing the performance of the octet. "Downstairs at Abbey Road, the eight guys assembled and they did it live...I would go down and say 'hi' and listen to it down there, which is always nice at first. They you go up and see what the engineers are making of it. Y'know, they'd put it all together, put the right little bits of fairy dust on it and they now made it like a record!".

One of the viola players, Stephen Shingles, remembers about that session: “I got about five pounds (the standard Musicians’ Union session fee was nine pounds) and it made billions of pounds. And like idiots we gave them all our ideas for free.” Being that they were going strictly off of George Martin’s pre-written score, it can easily be assumed that their “ideas” had to be minimal. One of the viola players, Stephen Shingles, remembers about that session: “I got about five pounds (the standard Musicians’ Union session fee was nine pounds) and it made billions of pounds. And like idiots we gave them all our ideas for free.” Being that they were going strictly off of George Martin’s pre-written score, it can easily be assumed that their “ideas” had to be minimal.

Geoff Emerick concludes: “In the end, the players did a good job, though they clearly were annoyed, so much so that they declined an invitation to listen to the playback. We didn’t really care what they thought, anyway – we were pleased that we had come up with another new sound, which was really a combination of Paul’s vision and mine.” Upon listening to this "Talking (Keep)" selection made available in the Deluxe editions of "Revolver," however, the listener can hear these studio musicians laughing and discussing their performances with George Martin, thus suggesting that maybe they weren't too "annoyed" as Geoff Emerick remembered. By 7:50 that evening, the session concluded for the day. Geoff Emerick concludes: “In the end, the players did a good job, though they clearly were annoyed, so much so that they declined an invitation to listen to the playback. We didn’t really care what they thought, anyway – we were pleased that we had come up with another new sound, which was really a combination of Paul’s vision and mine.” Upon listening to this "Talking (Keep)" selection made available in the Deluxe editions of "Revolver," however, the listener can hear these studio musicians laughing and discussing their performances with George Martin, thus suggesting that maybe they weren't too "annoyed" as Geoff Emerick remembered. By 7:50 that evening, the session concluded for the day.

At 5 pm the next evening, April 29th, 1966, another session took place at EMI Studios, this time in EMI Studio Three, to add the vocals to “Eleanor Rigby.” McCartney’s lead vocals were added to track four, John and George's harmony vocals during the intro and bridge added to track three, and an attempt at Paul double-tracking his lead vocal on track two. However, as caught on track two of the tape, Paul was unhappy with his double-tracking, stating, "It's crap, this one!" "I didn't think I was singing it well," Paul states in "McCartney 3,2,1." "I remember talking to George (Martin). I said, 'I'm not singing this (well)' He said, 'No, it's ok.' He was calming me down. And we double-tracked it, I think probably because I didn't think I'd sung it well. So when we would double-track it, we'd cover any sins." In the end, track two of this tape was not used, ADT ("Artificial Double Tracking") being applied to his lead vocal from track four during the final mixing stage. The song was considered complete by 1 am the next morning. Three mono mixes of the song were then produced by George Martin, Geoff Emerick and Phil McDonald, although neither of these were ever used. At 5 pm the next evening, April 29th, 1966, another session took place at EMI Studios, this time in EMI Studio Three, to add the vocals to “Eleanor Rigby.” McCartney’s lead vocals were added to track four, John and George's harmony vocals during the intro and bridge added to track three, and an attempt at Paul double-tracking his lead vocal on track two. However, as caught on track two of the tape, Paul was unhappy with his double-tracking, stating, "It's crap, this one!" "I didn't think I was singing it well," Paul states in "McCartney 3,2,1." "I remember talking to George (Martin). I said, 'I'm not singing this (well)' He said, 'No, it's ok.' He was calming me down. And we double-tracked it, I think probably because I didn't think I'd sung it well. So when we would double-track it, we'd cover any sins." In the end, track two of this tape was not used, ADT ("Artificial Double Tracking") being applied to his lead vocal from track four during the final mixing stage. The song was considered complete by 1 am the next morning. Three mono mixes of the song were then produced by George Martin, Geoff Emerick and Phil McDonald, although neither of these were ever used.

The reason they were never used was that, on June 6th, 1966, an idea to include an additional vocal passage in the conclusion of the song was recorded, making the previous mono mixes unusable. After assorted tape copying and mono mixing of recently recorded “Revolver” tracks were completed, Paul stuck around EMI Studio Three so that, at midnight, he could have a go at adding two vocal lines (“aah, look at all the lonely people”) to be superimposed on top of his previously recorded vocals in the conclusion of the song. By 1:30 the next morning, this was complete and so was “Eleanor Rigby.” The reason they were never used was that, on June 6th, 1966, an idea to include an additional vocal passage in the conclusion of the song was recorded, making the previous mono mixes unusable. After assorted tape copying and mono mixing of recently recorded “Revolver” tracks were completed, Paul stuck around EMI Studio Three so that, at midnight, he could have a go at adding two vocal lines (“aah, look at all the lonely people”) to be superimposed on top of his previously recorded vocals in the conclusion of the song. By 1:30 the next morning, this was complete and so was “Eleanor Rigby.”

Both of the released mono and stereo mixes of the hit song "Eleanor Rigby" were created during the final mixing session for the “Revolver” album on June 22nd, 1966. This was done in the control room of EMI Studio Three by George Martin and engineers Geoff Emerick and Jerry Boys. Paul's lead vocals in the mono mix are somewhat louder than the stereo. The stereo mix has the double string quartet centered while Paul’s lead vocals are entirely in the right channel when they are single tracked with the ADT track of his lead vocals centered in the mix during the choruses. A blatant error with the ADT occurs at the beginning of the first verse where the first two syllables of the word “Eleanor” are centered before they turn the ADT track down for the rest of the verse. The background harmonies and Paul’s final vocal overdub in the conclusion are all heard entirely in the left channel. Both of the released mono and stereo mixes of the hit song "Eleanor Rigby" were created during the final mixing session for the “Revolver” album on June 22nd, 1966. This was done in the control room of EMI Studio Three by George Martin and engineers Geoff Emerick and Jerry Boys. Paul's lead vocals in the mono mix are somewhat louder than the stereo. The stereo mix has the double string quartet centered while Paul’s lead vocals are entirely in the right channel when they are single tracked with the ADT track of his lead vocals centered in the mix during the choruses. A blatant error with the ADT occurs at the beginning of the first verse where the first two syllables of the word “Eleanor” are centered before they turn the ADT track down for the rest of the verse. The background harmonies and Paul’s final vocal overdub in the conclusion are all heard entirely in the left channel.

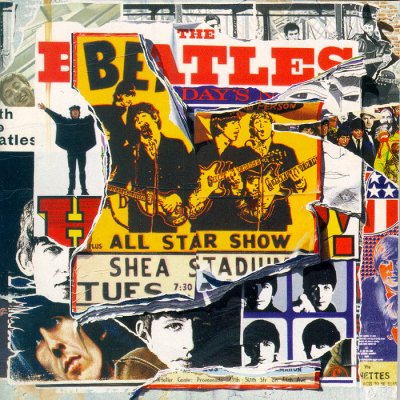

An instrumental stereo mix of "take 14" from the first four-track tape was made in 1995 by George Martin and Geoff Emerick for inclusion on the “Anthology 2” album, the strings being remixed for a good stereo presence. An instrumental stereo mix of "take 14" from the first four-track tape was made in 1995 by George Martin and Geoff Emerick for inclusion on the “Anthology 2” album, the strings being remixed for a good stereo presence.

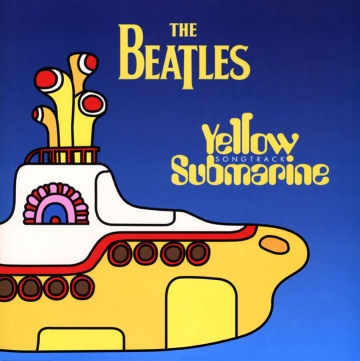

An entirely new stereo mix of the song was made in 1999 for its inclusion on the release “Yellow Submarine Songtrack.” This mix was performed in Abbey Road Studios (formerly EMI Studios) by the team of Peter Cobbin, Paul Hicks, Mirek Stiles and Allan Rouse. The string section was divided into the violins on the left channel and the violas and cellos on the right channel. All of the vocals were centered in the mix. An entirely new stereo mix of the song was made in 1999 for its inclusion on the release “Yellow Submarine Songtrack.” This mix was performed in Abbey Road Studios (formerly EMI Studios) by the team of Peter Cobbin, Paul Hicks, Mirek Stiles and Allan Rouse. The string section was divided into the violins on the left channel and the violas and cellos on the right channel. All of the vocals were centered in the mix.

Sometime between 2004 and 2006, George Martin and son Giles Martin created yet another stereo mix of “Eleanor Rigby” (with a transition from the song “Julia”) for the Cirque du Soleil soundtrack entitled “Love.” This mix combined the instrumental version with vocals for an extended presentation of the song. Sometime between 2004 and 2006, George Martin and son Giles Martin created yet another stereo mix of “Eleanor Rigby” (with a transition from the song “Julia”) for the Cirque du Soleil soundtrack entitled “Love.” This mix combined the instrumental version with vocals for an extended presentation of the song.

In 2015, Giles Martin once again turned his attention to the master tapes for "Eleanor Rigby" at Abbey Road Studios to create, along with Sam Okell, an even more vibrant stereo mix of the song for inclusion in the re-released 2015 version of the compilation album "Beatles 1." Giles Martin and Sam Okell returned to "Eleanor Rigby" yet again to create yet another stereo mix of the song sometime in 2022 for inclusion in the "Revolver" editions released that year. While they were at it, they also mixed the above-mentioned "Talking (Keep)" recording between "take one" and "take two" from the original session, as well as the complete instrumental "take two" for inclusion in the Deluxe editions. In 2015, Giles Martin once again turned his attention to the master tapes for "Eleanor Rigby" at Abbey Road Studios to create, along with Sam Okell, an even more vibrant stereo mix of the song for inclusion in the re-released 2015 version of the compilation album "Beatles 1." Giles Martin and Sam Okell returned to "Eleanor Rigby" yet again to create yet another stereo mix of the song sometime in 2022 for inclusion in the "Revolver" editions released that year. While they were at it, they also mixed the above-mentioned "Talking (Keep)" recording between "take one" and "take two" from the original session, as well as the complete instrumental "take two" for inclusion in the Deluxe editions.

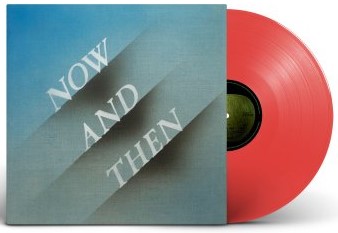

Giles Martin was also involved, along with Paul, in inserting a bit of the backing harmonies used in the original sessions of "Eleanor Rigby" into the final Beatles release "Now And Then," this occuring sometime in the later half of 2023. The insertion of these harmonies was accomplished at Abbey Road Studios by Giles Martin using the same methods he utilized in making the "Love" album detailed above, "Now And Then" being produced by Paul McCartney and Giles Martin (with Jeff Lynne as additional producer because of his work with the song in 1995) and mixed by Spike Stent. Giles Martin was also involved, along with Paul, in inserting a bit of the backing harmonies used in the original sessions of "Eleanor Rigby" into the final Beatles release "Now And Then," this occuring sometime in the later half of 2023. The insertion of these harmonies was accomplished at Abbey Road Studios by Giles Martin using the same methods he utilized in making the "Love" album detailed above, "Now And Then" being produced by Paul McCartney and Giles Martin (with Jeff Lynne as additional producer because of his work with the song in 1995) and mixed by Spike Stent.

Also to be mentioned is a new recording of the song by Paul McCartney in 1983 for inclusion on his soundtrack album “Give My Regards To Broad Street,” this being recorded at Abbey Road Studios in 1983 with George Martin as producer. On the album, this recording quickly segues into a similarly titled instrumental composition called “Eleanor’s Dream.” Also to be mentioned is a new recording of the song by Paul McCartney in 1983 for inclusion on his soundtrack album “Give My Regards To Broad Street,” this being recorded at Abbey Road Studios in 1983 with George Martin as producer. On the album, this recording quickly segues into a similarly titled instrumental composition called “Eleanor’s Dream.”

On February 8th, 1990, a live version of “Eleanor Rigby” was recorded by McCartney which was included on his “Tripping The Live Fantastic” and “Tripping The Live Fantastic: Highlights!” albums. Also, sometime in April or May of 2002, he recorded another live version of the song that was included on his “Back In The US” album. Then, in July of 2009, a further live rendition of the song was recorded at Citi Field in New York City for inclusion on his “Good Evening New York City” album. On February 8th, 1990, a live version of “Eleanor Rigby” was recorded by McCartney which was included on his “Tripping The Live Fantastic” and “Tripping The Live Fantastic: Highlights!” albums. Also, sometime in April or May of 2002, he recorded another live version of the song that was included on his “Back In The US” album. Then, in July of 2009, a further live rendition of the song was recorded at Citi Field in New York City for inclusion on his “Good Evening New York City” album.

Song Structure and Style

Without warning, Beatles fans (and popular music fans alike) were treated to a side-step into Classical music within the two-minute format of AM pop radio in 1966. Classical music buffs may shudder at my insinuation that “Eleanor Rigby” fits into that genre by any stretch of the imagination, but we can at least view it as a fusion with the popular music form of that era. Funnily enough, Beatles' enthusiasts of that decade (as well as later decades) accept this track as impressively entertaining and not too “high brow” for their taste. Without warning, Beatles fans (and popular music fans alike) were treated to a side-step into Classical music within the two-minute format of AM pop radio in 1966. Classical music buffs may shudder at my insinuation that “Eleanor Rigby” fits into that genre by any stretch of the imagination, but we can at least view it as a fusion with the popular music form of that era. Funnily enough, Beatles' enthusiasts of that decade (as well as later decades) accept this track as impressively entertaining and not too “high brow” for their taste.

The song's structure consists of a ‘intro/ verse/ verse/ chorus/ verse/ verse/ chorus/ bridge (intro)/ verse/ verse/ chorus (outro)’ format (or abbcbbcabbc). Beginning the proceedings with the bridge (thereby making it an intro to the song) is something that had been done before in their catalog, such as in “Can’t Buy Me Love,” which suggests a possible credit to George Martin for this arrangement element since it was his suggestion on the earlier song. The song's structure consists of a ‘intro/ verse/ verse/ chorus/ verse/ verse/ chorus/ bridge (intro)/ verse/ verse/ chorus (outro)’ format (or abbcbbcabbc). Beginning the proceedings with the bridge (thereby making it an intro to the song) is something that had been done before in their catalog, such as in “Can’t Buy Me Love,” which suggests a possible credit to George Martin for this arrangement element since it was his suggestion on the earlier song.

The listener is startled right at the downbeat of the very first measure of the song with its three-part harmony lyric “aaah, look at all the lonely people” (which suspiciously sounds like “lovely people” to a lot of ears) on top of the pulsing quarter notes of the octet of string musicians. The held out sighing melody line of the cellos and saw-like jumping eighth notes of the violins make for a very impressive but busy eight-measure introduction to the song. The listener is startled right at the downbeat of the very first measure of the song with its three-part harmony lyric “aaah, look at all the lonely people” (which suspiciously sounds like “lovely people” to a lot of ears) on top of the pulsing quarter notes of the octet of string musicians. The held out sighing melody line of the cellos and saw-like jumping eighth notes of the violins make for a very impressive but busy eight-measure introduction to the song.