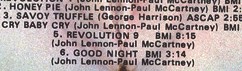

Search by Keyword

|

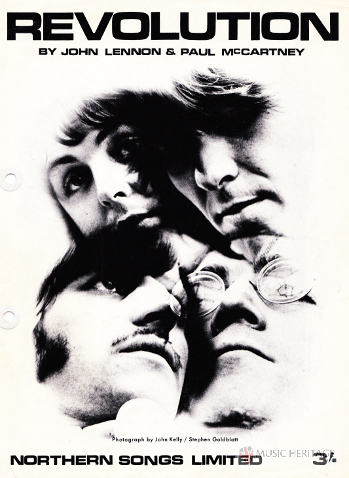

"REVOLUTION 1"

(John Lennon – Paul McCartney)

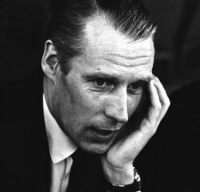

Brian Epstein, The Beatles' manager, was very concerned about presenting his group in the best possible light. He did allow putting them before the press for questioning whenever possible so as to promote a likable image to the masses. However, these press conferences, many times held locally in the locations of their tour dates, could have resulted in The Beatles giving their personal opinions about politics or world events. Radio and television interviews were also very common, so opportunities to express themselves to the masses were plentiful. Since strong feelings were held by the population regarding various issues, such as the Vietnam War, The Beatles were instructed to avoid answering questions about these issues so as not to alienate themselves from anyone. Brian Epstein, The Beatles' manager, was very concerned about presenting his group in the best possible light. He did allow putting them before the press for questioning whenever possible so as to promote a likable image to the masses. However, these press conferences, many times held locally in the locations of their tour dates, could have resulted in The Beatles giving their personal opinions about politics or world events. Radio and television interviews were also very common, so opportunities to express themselves to the masses were plentiful. Since strong feelings were held by the population regarding various issues, such as the Vietnam War, The Beatles were instructed to avoid answering questions about these issues so as not to alienate themselves from anyone.

While The Beatles were very sad about the death of Brian Epstein on August 27th, 1967, it had already become generally known to everyone that they were beginning to be more and more outspoken about what they felt and believed on many subjects. Even in 1966, they began speaking candidly about religion, drug use, and their disenchantment with live performances, all to the horror of their manager. And now that he sadly was out of the picture, they said whatever they wanted to, whenever they wanted to. While The Beatles were very sad about the death of Brian Epstein on August 27th, 1967, it had already become generally known to everyone that they were beginning to be more and more outspoken about what they felt and believed on many subjects. Even in 1966, they began speaking candidly about religion, drug use, and their disenchantment with live performances, all to the horror of their manager. And now that he sadly was out of the picture, they said whatever they wanted to, whenever they wanted to.

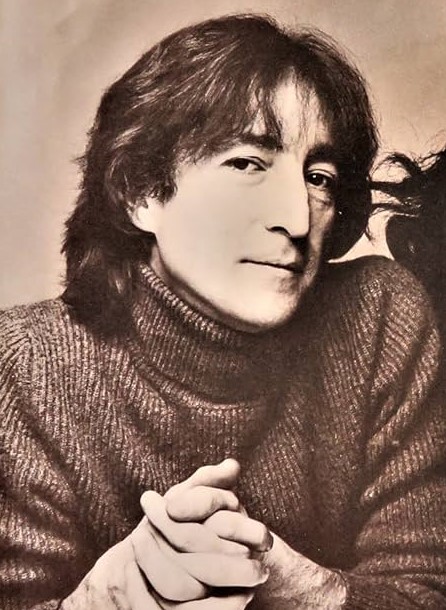

“I wanted to put out what I felt about revolution,” John stated in 1970. “I thought it was about time we spoke about it, the same as I thought it was about time we stopped not answering about the Vietnamese war when we were on tour with Brian Epstein and had to tell him, 'We're going to talk about the war this time and we're not going to just waffle'...That's why I did it: I wanted to talk, I wanted to say my piece about revolutions. I wanted to tell you, or whoever listens, to communicate, to say, 'What do you say?' 'This is what I say.'” “I wanted to put out what I felt about revolution,” John stated in 1970. “I thought it was about time we spoke about it, the same as I thought it was about time we stopped not answering about the Vietnamese war when we were on tour with Brian Epstein and had to tell him, 'We're going to talk about the war this time and we're not going to just waffle'...That's why I did it: I wanted to talk, I wanted to say my piece about revolutions. I wanted to tell you, or whoever listens, to communicate, to say, 'What do you say?' 'This is what I say.'”

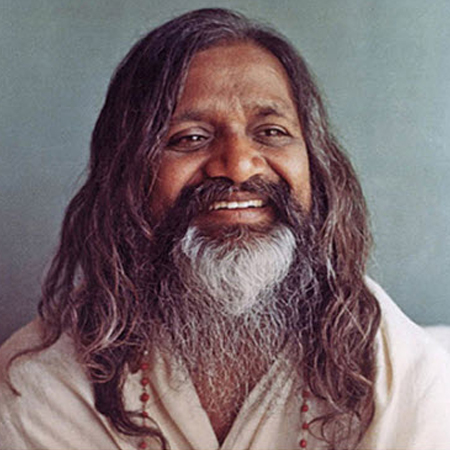

Songwriting History

“I had been thinking about it up in the hills in India,” John continued in a 1970 interview. “I still had this 'God will save us' feeling about it: 'It's going to be all right.'” This indicates that at least the seed of the idea for the song began germinating while The Beatles were in India in the spring of 1968 studying Transcendental Meditation with the Maharishi. It has been stated that the protests that year in opposition to the Vietnam War, as well as other polical issues in America, Britain and Poland, steered Lennon away form the "summer of love" mentality of 1967 into a mindset of a need for politcal change. “I had been thinking about it up in the hills in India,” John continued in a 1970 interview. “I still had this 'God will save us' feeling about it: 'It's going to be all right.'” This indicates that at least the seed of the idea for the song began germinating while The Beatles were in India in the spring of 1968 studying Transcendental Meditation with the Maharishi. It has been stated that the protests that year in opposition to the Vietnam War, as well as other polical issues in America, Britain and Poland, steered Lennon away form the "summer of love" mentality of 1967 into a mindset of a need for politcal change.

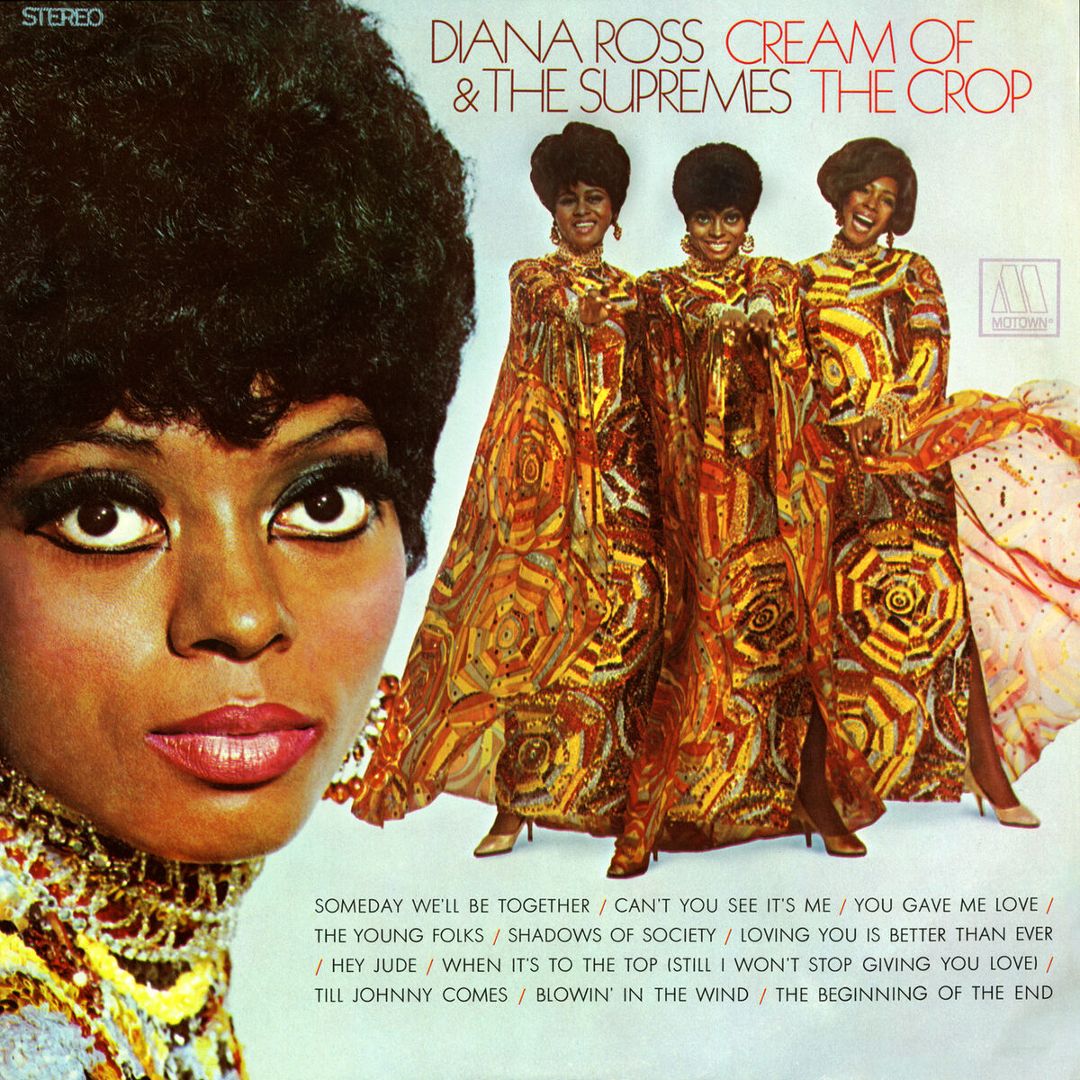

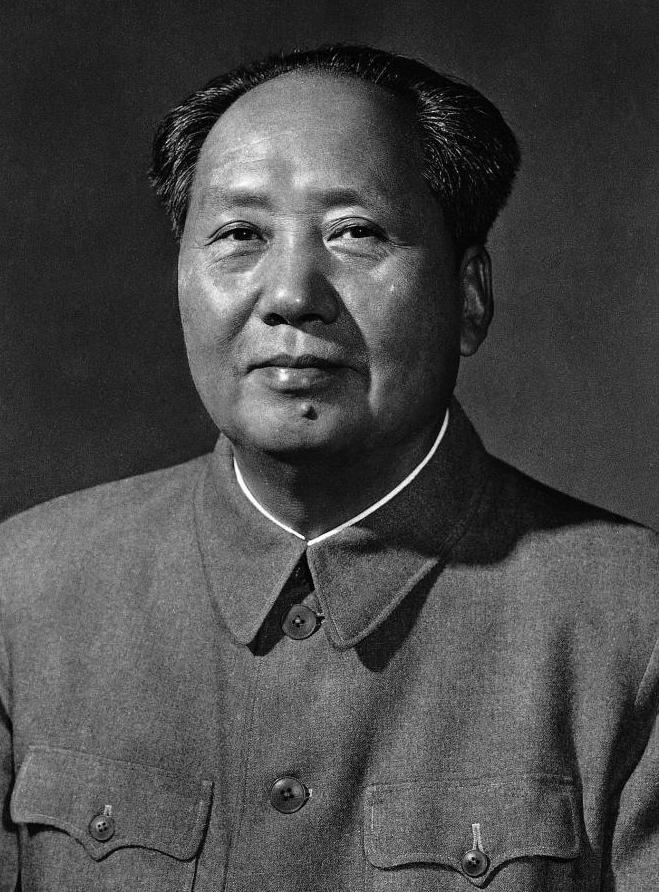

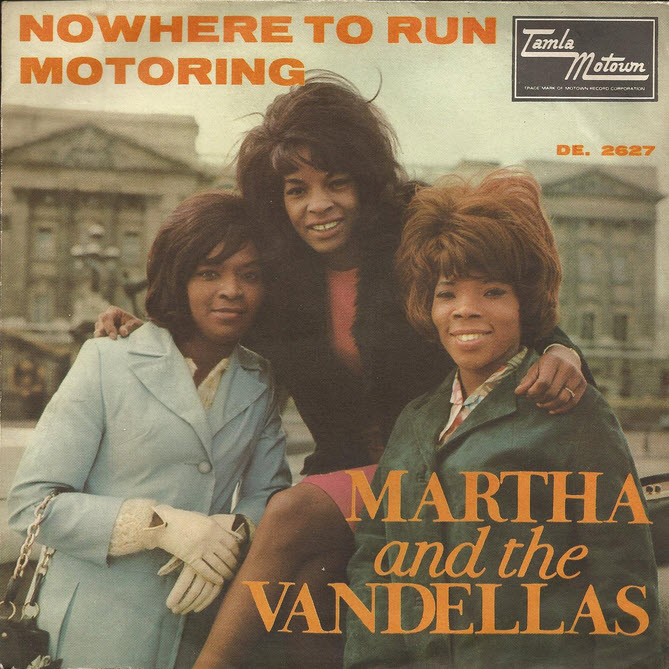

Most of the song was written as of May 28th, 1968, evidenced in a demo recording that was recorded on that day which included everything but the final verse with the "Chairman Mao" reference. John's original handwritten lyric sheet, which was numbered "8" in a songwriting notebook he was keeping in India, contains only the first two verses and some singing instructions at the top which reads, "Martha - Diana - light voice," undoubtedly stipulating that he wanted to sing the song with a feminine quality like his Motown favorites Martha Reeves and Diana Ross & The Supremes. The following page in John's notebook shows John experimenting with words that rhyme with "Revolution," such as "constitution," "institution," "polution," "dissolution" and "confusion." Most of the song was written as of May 28th, 1968, evidenced in a demo recording that was recorded on that day which included everything but the final verse with the "Chairman Mao" reference. John's original handwritten lyric sheet, which was numbered "8" in a songwriting notebook he was keeping in India, contains only the first two verses and some singing instructions at the top which reads, "Martha - Diana - light voice," undoubtedly stipulating that he wanted to sing the song with a feminine quality like his Motown favorites Martha Reeves and Diana Ross & The Supremes. The following page in John's notebook shows John experimenting with words that rhyme with "Revolution," such as "constitution," "institution," "polution," "dissolution" and "confusion."

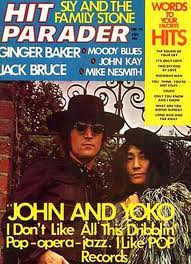

John's 1972 interview for Hit Parader Magazine includes his statement that he "should never have put that in about Chairman Mao," adding, "I was just finishing off in the studio when I did that." This is evidenced by an early typed lyric sheet John had for the song that shows this final verse was added in John's handwriting. This indicates that the final verse was written at the time of their first official recording session on May 30th, 1968. John's 1972 interview for Hit Parader Magazine includes his statement that he "should never have put that in about Chairman Mao," adding, "I was just finishing off in the studio when I did that." This is evidenced by an early typed lyric sheet John had for the song that shows this final verse was added in John's handwriting. This indicates that the final verse was written at the time of their first official recording session on May 30th, 1968.

John has been very vocal throughout the remaining years of his life regarding his intentions in the lyrics of the song. In 1968 he explained: “What I said in 'Revolution'...is 'change your head.' These people that are trying to change the world can't even get it all together. They're attacking and biting each others' faces, and all the time they're all pushing the same way. And if they keep going on like that it's going to kill it before it's even moved. It's silly to bitch about each other and be trivial. They've got to think in terms of at least the world or the universe, and stop thinking in terms of factories and one country.” John has been very vocal throughout the remaining years of his life regarding his intentions in the lyrics of the song. In 1968 he explained: “What I said in 'Revolution'...is 'change your head.' These people that are trying to change the world can't even get it all together. They're attacking and biting each others' faces, and all the time they're all pushing the same way. And if they keep going on like that it's going to kill it before it's even moved. It's silly to bitch about each other and be trivial. They've got to think in terms of at least the world or the universe, and stop thinking in terms of factories and one country.”

Continuing, John states: “The point is that the Establishment doesn't really exist, and if it does exist, it's old people. The only people that want to change it are young, and they're going to beat the Establishment. If they want to smash it all down, and have to be laborers as well to build it up again, then that's what they're going to get. If they'd just realize the Establishment can't last forever. The only reason it has lasted forever is that the only way people have ever tried to change it is by revolution. And the idea is just to move in on the scene, so they can take over the universities, do all the things that are practically feasible at the time. But not try and take over the state, or smash the state, or slow down the works. All they've got to do is get through and change it, because they will be it.” Continuing, John states: “The point is that the Establishment doesn't really exist, and if it does exist, it's old people. The only people that want to change it are young, and they're going to beat the Establishment. If they want to smash it all down, and have to be laborers as well to build it up again, then that's what they're going to get. If they'd just realize the Establishment can't last forever. The only reason it has lasted forever is that the only way people have ever tried to change it is by revolution. And the idea is just to move in on the scene, so they can take over the universities, do all the things that are practically feasible at the time. But not try and take over the state, or smash the state, or slow down the works. All they've got to do is get through and change it, because they will be it.”

During an appearance on the BBC 2 TV show "Release" on June 8th, 1968, a week and a half after The Beatles began recording the song in EMI Studios, John looked directly into the camera and pronounced: "I think our society is run by insane people for insane objectives. If anybody can put on paper what our government, and the American government, and the Russian, Chinese...what they are actually trying to do, and what they think they're doing, I'd be very pleased to know," this statement exemplifiying the lyric "We'd all love to see the plan" that he had just sung in the recording of what came to be known as "Revolution 1." In 1969, he added: “The only way to ensure a lasting peace of any kind is to change people's minds. There's no other way. The Government can do it with propaganda. Coca-Cola can do it with propaganda – why can't we? We are the hip generation." In fact, the lyric "you better free your mind instead" is a reflection of the teaching of the Maharishi about Transcendental Meditation, where it has been proven that crime can be reduced in specific regions with the concentrated use of TM. During an appearance on the BBC 2 TV show "Release" on June 8th, 1968, a week and a half after The Beatles began recording the song in EMI Studios, John looked directly into the camera and pronounced: "I think our society is run by insane people for insane objectives. If anybody can put on paper what our government, and the American government, and the Russian, Chinese...what they are actually trying to do, and what they think they're doing, I'd be very pleased to know," this statement exemplifiying the lyric "We'd all love to see the plan" that he had just sung in the recording of what came to be known as "Revolution 1." In 1969, he added: “The only way to ensure a lasting peace of any kind is to change people's minds. There's no other way. The Government can do it with propaganda. Coca-Cola can do it with propaganda – why can't we? We are the hip generation." In fact, the lyric "you better free your mind instead" is a reflection of the teaching of the Maharishi about Transcendental Meditation, where it has been proven that crime can be reduced in specific regions with the concentrated use of TM.

In 1970, he elaborated: “If you want peace, you won't get it with violence. Please tell me one militant revolution that worked. Sure, a few of them took over, but what happened? Status quo. And if they smash it down, who do they think is going to build it up again? And then when they've built it up again, who do they think is going to run it? And how are they going to run it? They don't look further than their noses.” In 1970, he elaborated: “If you want peace, you won't get it with violence. Please tell me one militant revolution that worked. Sure, a few of them took over, but what happened? Status quo. And if they smash it down, who do they think is going to build it up again? And then when they've built it up again, who do they think is going to run it? And how are they going to run it? They don't look further than their noses.”

In 1971, he stated: “These left-wing people talk about giving the power to the people. That's nonsense – the people have the power. All we're trying to do is make people aware that they have the power themselves, and the violent way of revolution doesn't justify the ends. All we're trying to say to people is to expose politicians and expose the people themselves who are hypocritical and sitting back and saying, 'Oh, we can't do anything about it, it's up to somebody else. Give us the answer, John.' People have to organize. Students have to organize voting.” In 1971, he stated: “These left-wing people talk about giving the power to the people. That's nonsense – the people have the power. All we're trying to do is make people aware that they have the power themselves, and the violent way of revolution doesn't justify the ends. All we're trying to say to people is to expose politicians and expose the people themselves who are hypocritical and sitting back and saying, 'Oh, we can't do anything about it, it's up to somebody else. Give us the answer, John.' People have to organize. Students have to organize voting.”

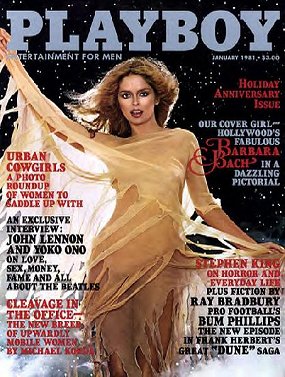

In his 1980 Playboy Magazine interview, John gives an overall perspective from twelve years later. “You look at the song and see my feelings about politics, radicalism and everything. I want to see the plan. Waving Chairman Mao badges or being a Marxist or a thisist or a thatist is going to get you shot, locked up. If that's what you want, you subconsciously want to be a martyr. You see, I want to know what you are going to do after you have knocked it all down. Can't we use some of it? If you want to change the system, change the system. Don't go shooting people.” In his 1980 Playboy Magazine interview, John gives an overall perspective from twelve years later. “You look at the song and see my feelings about politics, radicalism and everything. I want to see the plan. Waving Chairman Mao badges or being a Marxist or a thisist or a thatist is going to get you shot, locked up. If that's what you want, you subconsciously want to be a martyr. You see, I want to know what you are going to do after you have knocked it all down. Can't we use some of it? If you want to change the system, change the system. Don't go shooting people.”

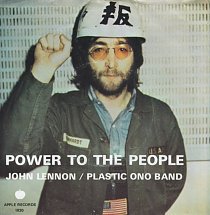

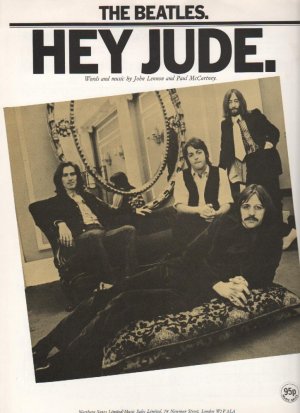

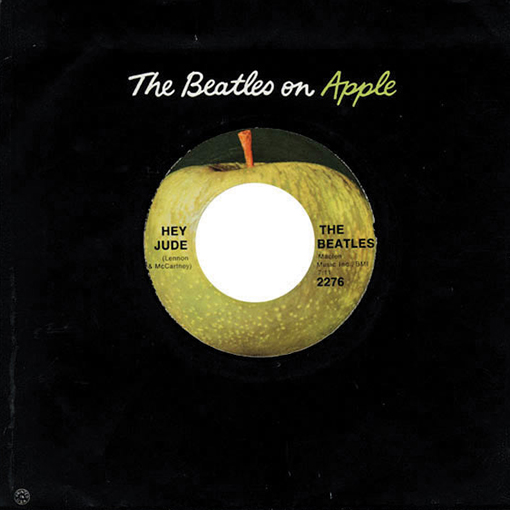

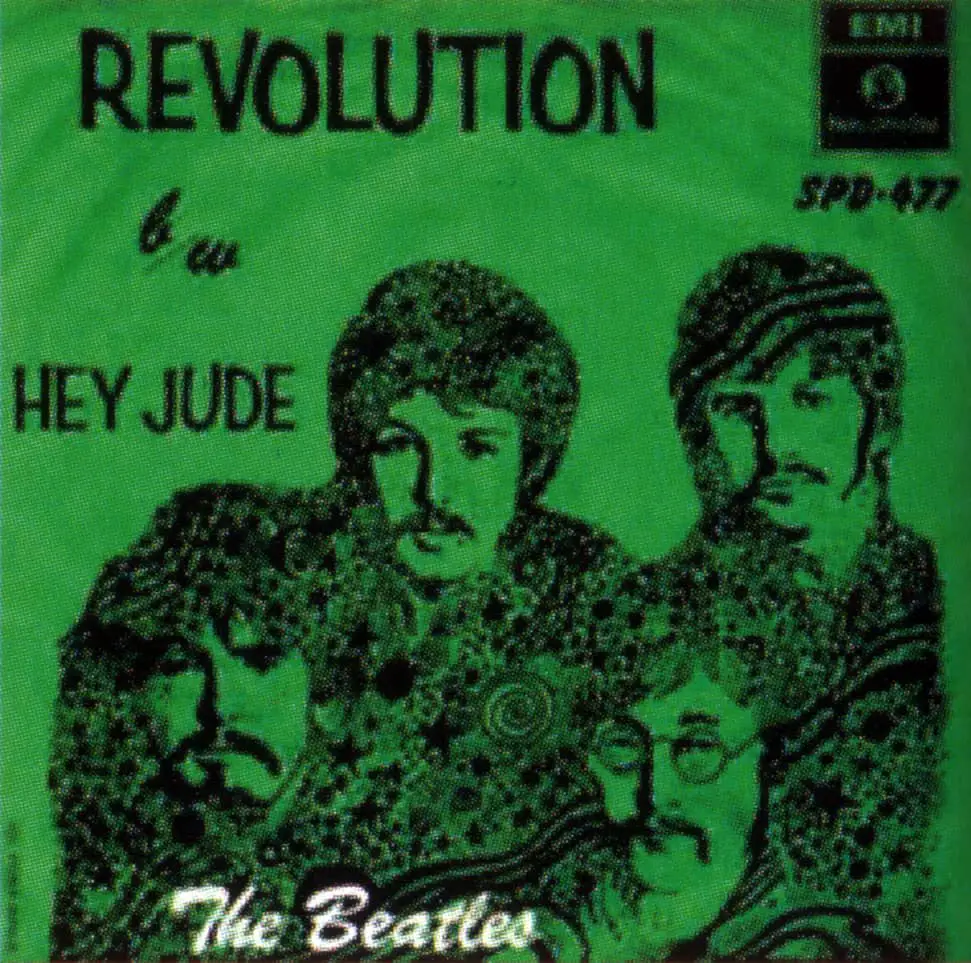

.jpg) Most music fans will probably be more familiar with the version of this song that was released as the b-side to the single “Hey Jude,” this version simply titled “Revolution.” However, “Revolution 1,” the first version to be recorded, is lyrically noteworthy because of the altered line, “but when you talk about destruction, don't you know that you can count me out...in.” Most music fans will probably be more familiar with the version of this song that was released as the b-side to the single “Hey Jude,” this version simply titled “Revolution.” However, “Revolution 1,” the first version to be recorded, is lyrically noteworthy because of the altered line, “but when you talk about destruction, don't you know that you can count me out...in.”

John explains this lyric in a 1971 interview: “There were two versions of that song, but the underground left only picked up on the one that said 'count me out.' The original version, which ends up on the LP, said 'count me in' too; I put in both because I wasn't sure. I didn't want to get killed. I didn't really know much about the Maoists, but I just knew that they seemed to be so few and yet they painted themselves green and stood in front of the police waiting to get picked off. I just thought it was unsubtle. I thought the original Communist revolutionaries coordinated themselves a bit better and didn't go around shouting about it.” John explains this lyric in a 1971 interview: “There were two versions of that song, but the underground left only picked up on the one that said 'count me out.' The original version, which ends up on the LP, said 'count me in' too; I put in both because I wasn't sure. I didn't want to get killed. I didn't really know much about the Maoists, but I just knew that they seemed to be so few and yet they painted themselves green and stood in front of the police waiting to get picked off. I just thought it was unsubtle. I thought the original Communist revolutionaries coordinated themselves a bit better and didn't go around shouting about it.”

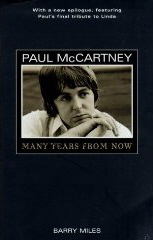

In his book “Many Years From Now,” Paul relates his thoughts on John's sentiment in “Revolution 1”: “It was a great song, basically John's. He doesn't really get off the fence in it. He says 'you can count me out - in,' so you're not actually sure. I don't think he was sure which way he felt about it at the time, but it was an overtly political song about revolution and a great one. I think John later ascribed more political intent to it than he actually felt when he wrote it.” In his book “Many Years From Now,” Paul relates his thoughts on John's sentiment in “Revolution 1”: “It was a great song, basically John's. He doesn't really get off the fence in it. He says 'you can count me out - in,' so you're not actually sure. I don't think he was sure which way he felt about it at the time, but it was an overtly political song about revolution and a great one. I think John later ascribed more political intent to it than he actually felt when he wrote it.”

Continuing, Paul writes: "They were very political times, obviously, with the Vietnam war going on, Chairman Mao and the Little Red Book, and all the demonstrations with people going through the streets shouting 'Ho, Ho Ho Chi Minh!' I think he wanted to say you can count me in for a revolution, but if you go carrying pictures of Chairman Mao 'you ain't gonna make it with anyone anyhow.' By saying that I think he meant we all want to change the world Maharishi-style, because 'Across The Universe' also had the change-the-world theme...John was just hedging his bets, covering all eventualities." Continuing, Paul writes: "They were very political times, obviously, with the Vietnam war going on, Chairman Mao and the Little Red Book, and all the demonstrations with people going through the streets shouting 'Ho, Ho Ho Chi Minh!' I think he wanted to say you can count me in for a revolution, but if you go carrying pictures of Chairman Mao 'you ain't gonna make it with anyone anyhow.' By saying that I think he meant we all want to change the world Maharishi-style, because 'Across The Universe' also had the change-the-world theme...John was just hedging his bets, covering all eventualities."

James Taylor, as quoted in his biography "Long Ago And Far Away: James Taylor, His Life And Music," recounts his association with John Lennon in 1968 when he was signed to Apple Records. "I had a couple of conversations with John during that early time in the studio and I remember him as being very busy and devoted to his craft...His energy was very intense and he believed very passionately about most of what he wrote. It was obvious that ("Revolution") was a response to a lot of people making demands on him concerning his radical point of view, and you realized that by our adulation of the group, we were all making it more and more difficult for them to continue. But they must have had a positive will beyond what I could contemplate, and John especially was writing a lot and doing very adventurous things." James Taylor, as quoted in his biography "Long Ago And Far Away: James Taylor, His Life And Music," recounts his association with John Lennon in 1968 when he was signed to Apple Records. "I had a couple of conversations with John during that early time in the studio and I remember him as being very busy and devoted to his craft...His energy was very intense and he believed very passionately about most of what he wrote. It was obvious that ("Revolution") was a response to a lot of people making demands on him concerning his radical point of view, and you realized that by our adulation of the group, we were all making it more and more difficult for them to continue. But they must have had a positive will beyond what I could contemplate, and John especially was writing a lot and doing very adventurous things."

By McCartney's above statement that the song was “basically John's” along with Lennon's 1980 interviews explaining “the statement in 'Revolution' was mine” and "completely me," we can easily deduce that Paul's input in the song's writing was very minimal at best. Musically, however, the song's intro is so eerily similar to Pee Wee Crayton's 1954 single "Do Unto Others" that it can easily be pointed to as an inspiration for John, if only subconsciously. By McCartney's above statement that the song was “basically John's” along with Lennon's 1980 interviews explaining “the statement in 'Revolution' was mine” and "completely me," we can easily deduce that Paul's input in the song's writing was very minimal at best. Musically, however, the song's intro is so eerily similar to Pee Wee Crayton's 1954 single "Do Unto Others" that it can easily be pointed to as an inspiration for John, if only subconsciously.

Recording History

The first time “Revolution” was committed to tape was on May 28th, 1968 when The Beatles all convened at George's "Kinfauns" home in Esher, Surrey, to create demo recordings of songs they were going to include on their next album. These recordings were made using George's four-track Ampex tape recorder, the group taking turns acoustically displaying their newly written songs and then performing various overdubs as ideas of what they would do officially when they got to EMI Studios. The first time “Revolution” was committed to tape was on May 28th, 1968 when The Beatles all convened at George's "Kinfauns" home in Esher, Surrey, to create demo recordings of songs they were going to include on their next album. These recordings were made using George's four-track Ampex tape recorder, the group taking turns acoustically displaying their newly written songs and then performing various overdubs as ideas of what they would do officially when they got to EMI Studios.

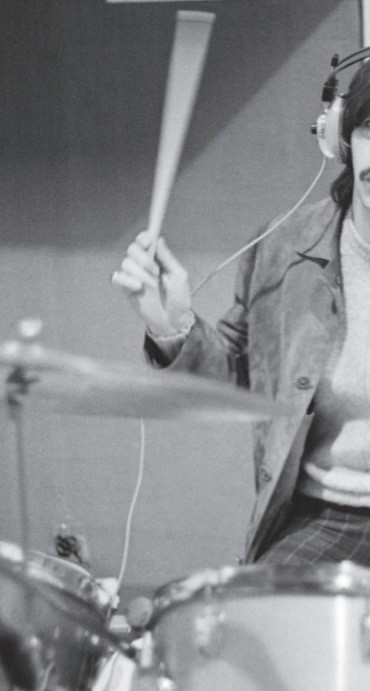

The demo recording of “Revolution” is delivered in a lighthearted and spirited way, conveying the semi-political lyrics in a way that one could easily envision as their next single. John plays acoustic guitar and sings while the other Beatles clap along and occasionally join in on backing vocals with a great sense of harmony. John then double-tracks himself on acoustic guitar and vocals but, as the final verse begins to kick in, his timing gets noticeably off. This results in the overdubbed tambourine in this verse, probably played by Ringo, having to compensate in order to catch the beat correctly (this awkwardness being corrected for this version's 50th Anniversary "White Album" releases). All in all, while containing flaws, this acoustic version is very impressive and paints a very accurate picture of how Lennon originally intended the song to sound. The demo recording of “Revolution” is delivered in a lighthearted and spirited way, conveying the semi-political lyrics in a way that one could easily envision as their next single. John plays acoustic guitar and sings while the other Beatles clap along and occasionally join in on backing vocals with a great sense of harmony. John then double-tracks himself on acoustic guitar and vocals but, as the final verse begins to kick in, his timing gets noticeably off. This results in the overdubbed tambourine in this verse, probably played by Ringo, having to compensate in order to catch the beat correctly (this awkwardness being corrected for this version's 50th Anniversary "White Album" releases). All in all, while containing flaws, this acoustic version is very impressive and paints a very accurate picture of how Lennon originally intended the song to sound.

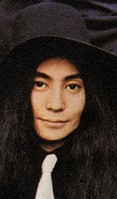

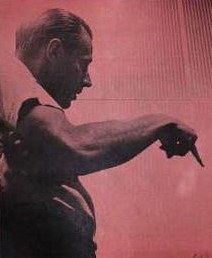

John, Paul and Ringo, along with John's new love interest Yoko Ono, entered EMI Studios on May 30th, 1968 to begin the first recording session for what became the “White Album.” Incidentally, May 20th was actually booked in advance to be the first recording session, as were the following Monday through Friday weekdays for the next ten weeks, but these first eight sessions were ultimately canceled. George did not perform on the recordings made on this day, so there is some question as to whether he was present. Someone who was present, however, was producer George Martin's new assistant, 21-year-old Chris Thomas, who was instrumental in the making of the entire "White Album." "I worked on stuff with them but basically they produced the sessions themselves when George went away (on vacation). It was John Lennon who insisted that I have a credit on the album's pullout sheet." They entered EMI Studio Two on this day at 2:30 pm ready to start recording what John felt should be the next Beatles single, the title of the song being simply “Revolution” at this point. John, Paul and Ringo, along with John's new love interest Yoko Ono, entered EMI Studios on May 30th, 1968 to begin the first recording session for what became the “White Album.” Incidentally, May 20th was actually booked in advance to be the first recording session, as were the following Monday through Friday weekdays for the next ten weeks, but these first eight sessions were ultimately canceled. George did not perform on the recordings made on this day, so there is some question as to whether he was present. Someone who was present, however, was producer George Martin's new assistant, 21-year-old Chris Thomas, who was instrumental in the making of the entire "White Album." "I worked on stuff with them but basically they produced the sessions themselves when George went away (on vacation). It was John Lennon who insisted that I have a credit on the album's pullout sheet." They entered EMI Studio Two on this day at 2:30 pm ready to start recording what John felt should be the next Beatles single, the title of the song being simply “Revolution” at this point.

Geoff Emerick, in his book “Here, There And Everywhere,” remembers vivid details of this session: “As usual, we were starting the album with one of John's songs: 'Revolution 1' – the slow version that would open side four of the vinyl release. Paul seemed unusually subdued that night; perhaps he was annoyed that John was dominating the proceedings so much. As the band began rehearsals, I noticed that they were playing louder than ever before; John in particular had turned his guitar amp up to an ear-splitting level. Eventually I got on the talkback and politely asked him to turn it down because there was so much leakage on all the other microphones. John's response was to shoot me a look to kill.” Geoff Emerick, in his book “Here, There And Everywhere,” remembers vivid details of this session: “As usual, we were starting the album with one of John's songs: 'Revolution 1' – the slow version that would open side four of the vinyl release. Paul seemed unusually subdued that night; perhaps he was annoyed that John was dominating the proceedings so much. As the band began rehearsals, I noticed that they were playing louder than ever before; John in particular had turned his guitar amp up to an ear-splitting level. Eventually I got on the talkback and politely asked him to turn it down because there was so much leakage on all the other microphones. John's response was to shoot me a look to kill.”

“'I've got something to say to you,' he sneered acidly. 'It's your job to control it, so just do your bloody job.' Upstairs, George Martin and I exchanged wary glances. 'I think you'd better go talk to him,' he said timidly. I was boggled. 'Why me? You're the producer,' I thought. But George was steadfastly refusing to get involved, so the ball was in my court. I made a point of walking down the steps leading to the studio slowly and deliberately. By the time I arrived, Lennon had calmed down a little. 'Look, the reason I've got my amp turned up so high is that I'm trying to distort the sh*t out of it,' he explained. 'If you need me to turn it down, I will, but you have to do something to get my guitar to sound a lot more nasty. That's what I'm after for this song.'” “'I've got something to say to you,' he sneered acidly. 'It's your job to control it, so just do your bloody job.' Upstairs, George Martin and I exchanged wary glances. 'I think you'd better go talk to him,' he said timidly. I was boggled. 'Why me? You're the producer,' I thought. But George was steadfastly refusing to get involved, so the ball was in my court. I made a point of walking down the steps leading to the studio slowly and deliberately. By the time I arrived, Lennon had calmed down a little. 'Look, the reason I've got my amp turned up so high is that I'm trying to distort the sh*t out of it,' he explained. 'If you need me to turn it down, I will, but you have to do something to get my guitar to sound a lot more nasty. That's what I'm after for this song.'”

“The request wasn't entirely unreasonable – heavily distorted guitars were being made fashionable by artists like Cream and Jimi Hendrix – and I was about to tell him, 'Okay, fine, I'll think of something...,' but then John couldn't resist one last jab, as he imperiously dismissed me with a wave of his arm. 'Come on, get with it, Geoff. I think it's about bloody time you got your act together.' 'F*ck you, John,' I thought. I was incensed, but I kept my mouth shut. Weren't we supposed to be working as a team? The moment I returned to the control room, George (Martin) and Phil (McDonald) could see just how furious I was. 'What's he on about?' George asked me. I was so mad I couldn't even answer.” “The request wasn't entirely unreasonable – heavily distorted guitars were being made fashionable by artists like Cream and Jimi Hendrix – and I was about to tell him, 'Okay, fine, I'll think of something...,' but then John couldn't resist one last jab, as he imperiously dismissed me with a wave of his arm. 'Come on, get with it, Geoff. I think it's about bloody time you got your act together.' 'F*ck you, John,' I thought. I was incensed, but I kept my mouth shut. Weren't we supposed to be working as a team? The moment I returned to the control room, George (Martin) and Phil (McDonald) could see just how furious I was. 'What's he on about?' George asked me. I was so mad I couldn't even answer.”

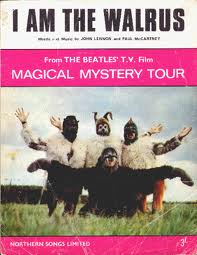

“After taking a few minutes to regain my composure, I decided to overload the mic preamp that was carrying John's guitar signal. It was basically the same trick I had done to put his voice 'over the moon' when he sang 'I Am The Walrus.' That satisfied John to some degree, but I could see that he was good and pissed off that it had taken me a period of time to get the sound sorted out. At the best of times, Lennon had limited patience, and tonight he seemed to have almost none. Fuming and sputtering, he pushed the band to play the song over and over again.” “After taking a few minutes to regain my composure, I decided to overload the mic preamp that was carrying John's guitar signal. It was basically the same trick I had done to put his voice 'over the moon' when he sang 'I Am The Walrus.' That satisfied John to some degree, but I could see that he was good and pissed off that it had taken me a period of time to get the sound sorted out. At the best of times, Lennon had limited patience, and tonight he seemed to have almost none. Fuming and sputtering, he pushed the band to play the song over and over again.”

Eighteen takes of the rhythm track were recorded, although there were no "take 11" or "take 12" for some reason. The instrumentation consisted of John on acoustic guitar (with the overloaded mic preamp), Paul on piano and Ringo on drums, all recorded onto track one of the four-track tape. Each of these takes were of various lengths, but they averaged around five minutes each Eighteen takes of the rhythm track were recorded, although there were no "take 11" or "take 12" for some reason. The instrumentation consisted of John on acoustic guitar (with the overloaded mic preamp), Paul on piano and Ringo on drums, all recorded onto track one of the four-track tape. Each of these takes were of various lengths, but they averaged around five minutes each

Before "take 13" began, Paul improvised the song with the lyrics "Civil war is raging in France, the generals cannot cope." This was in reaction to the events of this day, 400,000 protestors marching through the streets of Paris demanding the resignation of President Charles de Gaulle. The day before, the President failed in his attempt to meet with General Jacques Massu to squelch the unrest sparked by student demonstrations and strikes by millions of workers in France. Before "take 13" began, Paul improvised the song with the lyrics "Civil war is raging in France, the generals cannot cope." This was in reaction to the events of this day, 400,000 protestors marching through the streets of Paris demanding the resignation of President Charles de Gaulle. The day before, the President failed in his attempt to meet with General Jacques Massu to squelch the unrest sparked by student demonstrations and strikes by millions of workers in France.

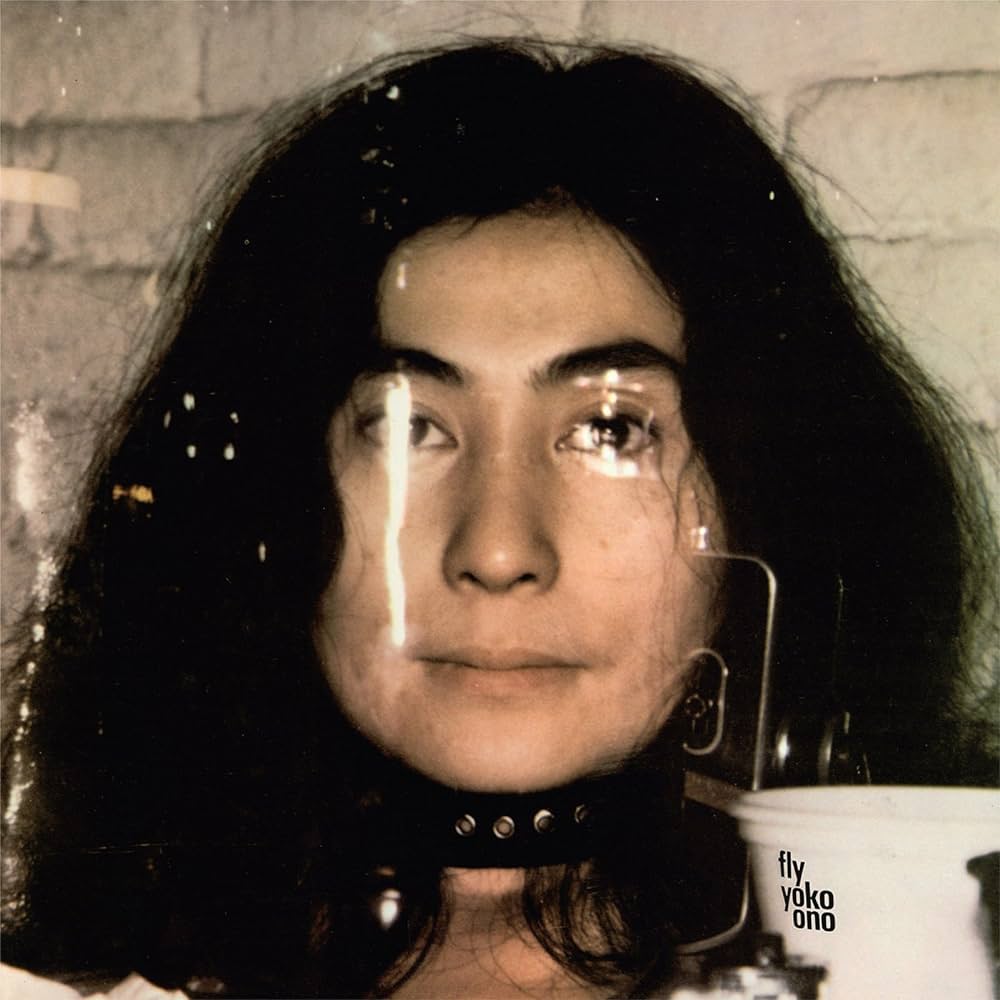

"Take 14" was noteworthy because of unexplained sounds that were coming through on open microphones, which baffled George Martin and Geoff Emerick. When they inquired what these sounds were, John replied, "It was a tape recorder. Yoko's playing the tape." Yoko Ono had previously recorded some spoken word recitations with sound effects that she thought she would add to the official recording in the studio, this apparently having John's approval. "Take 14" was noteworthy because of unexplained sounds that were coming through on open microphones, which baffled George Martin and Geoff Emerick. When they inquired what these sounds were, John replied, "It was a tape recorder. Yoko's playing the tape." Yoko Ono had previously recorded some spoken word recitations with sound effects that she thought she would add to the official recording in the studio, this apparently having John's approval.

Mark Lewisohn, in his book “The Beatles Recording Sessions,” describes the final take of the night. “'Take 18' was different, substantially different, and it was the basis of the final LP version. It began so soon after the previous take that Geoff Emerick, in punching the talkback button simultaneously with the start of the song, announced 'take 18'...John deliberately kept (Geoff) Emerick's words as part of the song and thus they appear on the album. Secondly, this take did not stop after five minutes. It kept on and on and on, eventually running out at 10:17...The last six minutes were pure chaos...with discordant instrumental jamming, plenty of feedback." Geoff Emerick adds: "Ringo looked like he was about to keel over...That first night's session was uncontrolled chaos, pure and simple, and George Martin had looked puzzled and concerned from start to finish. He and I knew that something was not quite right here, and I found myself thinking: What am I setting myself up for?” Mark Lewisohn, in his book “The Beatles Recording Sessions,” describes the final take of the night. “'Take 18' was different, substantially different, and it was the basis of the final LP version. It began so soon after the previous take that Geoff Emerick, in punching the talkback button simultaneously with the start of the song, announced 'take 18'...John deliberately kept (Geoff) Emerick's words as part of the song and thus they appear on the album. Secondly, this take did not stop after five minutes. It kept on and on and on, eventually running out at 10:17...The last six minutes were pure chaos...with discordant instrumental jamming, plenty of feedback." Geoff Emerick adds: "Ringo looked like he was about to keel over...That first night's session was uncontrolled chaos, pure and simple, and George Martin had looked puzzled and concerned from start to finish. He and I knew that something was not quite right here, and I found myself thinking: What am I setting myself up for?”

Just before "take 18" begins, as heard on the Super Deluxe 50th Anniversary edition of the "White Album," everyone is heard laughing and joking around, Paul humorously announcing the next take off mic as "take three?" John then replies, "Didn't we go?" and then says "Have one yourself," along with other indecipherable utterances from Paul and Yoko. During the introduction, we hear some loud unidentifiable percussive sounds that some describe as a washboard-style instrument, presumably played by Yoko, that may have been found in the sound effects cupboard of Studio Two, this effect making it onto the released recording. Realizing that this take was extending into a jam, Paul began vocalizing randomly while vamping on the piano, delving into some "shooby-doo, whop-bow" backing harmony with John also joining in. Eventually, Paul sang a verse of "Love Me Do," which even prompted Ringo to perform his standard 'Beatles break' as on the original recording. After the song finally grinds to a halt, Yoko's pre-recorded tape is placed in front of a microphone while Paul tinkles on the piano until her voice on the tape says "maybe if you become naked." Someone then yells "wooh" which prompts John to click off the tape player and laughingly say, "Let's hear it." As both he and Yoko laugh, she says, "It's too much," to which John concurs, "Wasn't it great?" Just before "take 18" begins, as heard on the Super Deluxe 50th Anniversary edition of the "White Album," everyone is heard laughing and joking around, Paul humorously announcing the next take off mic as "take three?" John then replies, "Didn't we go?" and then says "Have one yourself," along with other indecipherable utterances from Paul and Yoko. During the introduction, we hear some loud unidentifiable percussive sounds that some describe as a washboard-style instrument, presumably played by Yoko, that may have been found in the sound effects cupboard of Studio Two, this effect making it onto the released recording. Realizing that this take was extending into a jam, Paul began vocalizing randomly while vamping on the piano, delving into some "shooby-doo, whop-bow" backing harmony with John also joining in. Eventually, Paul sang a verse of "Love Me Do," which even prompted Ringo to perform his standard 'Beatles break' as on the original recording. After the song finally grinds to a halt, Yoko's pre-recorded tape is placed in front of a microphone while Paul tinkles on the piano until her voice on the tape says "maybe if you become naked." Someone then yells "wooh" which prompts John to click off the tape player and laughingly say, "Let's hear it." As both he and Yoko laugh, she says, "It's too much," to which John concurs, "Wasn't it great?"

As stated above, this was the first day of the "White Album" sessions that Yoko Ono was present in the studio, she becoming a near permanent fixture during Beatles recording sessions from here on out. “John brought her into the control room of (EMI) number three at the start of the 'White Album' sessions,” remembers Geoff Emerick. “He quickly introduced her to everyone and that was it. She was always by his side after that.” As stated above, this was the first day of the "White Album" sessions that Yoko Ono was present in the studio, she becoming a near permanent fixture during Beatles recording sessions from here on out. “John brought her into the control room of (EMI) number three at the start of the 'White Album' sessions,” remembers Geoff Emerick. “He quickly introduced her to everyone and that was it. She was always by his side after that.”

"Because we'd been such a tight-knit group, the fact that John was getting pretty serious about Yoko at that time, I can see now that he was enjoying his newfound freedom and getting excited by it,” Paul related to Q Magazine in 2013. “But when she turned up in the studio and sat in the middle of us doing nothing, I still admit now that we were all cheesed off...Lots of things that went down were good for us, really. At the time, though, we certainly did not think that." "Because we'd been such a tight-knit group, the fact that John was getting pretty serious about Yoko at that time, I can see now that he was enjoying his newfound freedom and getting excited by it,” Paul related to Q Magazine in 2013. “But when she turned up in the studio and sat in the middle of us doing nothing, I still admit now that we were all cheesed off...Lots of things that went down were good for us, really. At the time, though, we certainly did not think that."

There apparently were a couple other visitors to the session this day, both of which contributed to the recording. According to Kenneth Womack's book "Living The Beatles Legend: The Untold Story Of Mal Evans," Chris O'Dell, who had been recently hired as receptionist at Apple Corps, "asked Paul if she could visit the studio to see The Beatles at work. 'In my naivete, I didn't know that you weren't supposed to do that,' she said. For his part, Paul instructed her to 'talk to Mal.' It was a mantra she heard over and over again during her days at EMI Studios. That night, as she waited outside the studio, 'Mal was very friendly and very nice. We chatted about all kinds of things'...Moments later, John's boyhood friend Pete Shotton arrived on the scene, informing Mal that he was needed inside. With Mal having left to tend to the boys' needs, Pete asked Chris if she'd like to join him inside Studio 2, and within a matter of minutes, she was standing among John, Paul and George on the studio floor, providing staccato handclaps, along with Pete, for 'Revolution 1.'" There apparently were a couple other visitors to the session this day, both of which contributed to the recording. According to Kenneth Womack's book "Living The Beatles Legend: The Untold Story Of Mal Evans," Chris O'Dell, who had been recently hired as receptionist at Apple Corps, "asked Paul if she could visit the studio to see The Beatles at work. 'In my naivete, I didn't know that you weren't supposed to do that,' she said. For his part, Paul instructed her to 'talk to Mal.' It was a mantra she heard over and over again during her days at EMI Studios. That night, as she waited outside the studio, 'Mal was very friendly and very nice. We chatted about all kinds of things'...Moments later, John's boyhood friend Pete Shotton arrived on the scene, informing Mal that he was needed inside. With Mal having left to tend to the boys' needs, Pete asked Chris if she'd like to join him inside Studio 2, and within a matter of minutes, she was standing among John, Paul and George on the studio floor, providing staccato handclaps, along with Pete, for 'Revolution 1.'"

At any rate, at around 2:40 am the following morning, this twelve hour session was complete, The Beatles and company leaving to get some needed rest before returning about twelve hours later to add more overdubs to the song.

Later that day, May 31st, 1968, The Beatles met up again at 2:30 pm at EMI Studios, this time in the smaller Studio Three. The first order of business was to perform overdubs onto the three open tracks of the four-track tape of "take 18." The first of these was John's lead vocals onto track two, accompanied by various electronic squeaks, presumably performed by Yoko. Technical engineer Alan Brown, new to EMI since November of 1967, was present on this day and remembers the rehearsals of this overdub. “I was in the control room of Studio Three and there on the other side of the glass was a figure in semi-darkness going over and over some lines of a song. I knew the voice and sure enough I knew the face. John Lennon was about 30 feet away! He was working on 'Revolution,' the slow one, and I remember him going through the song again and again in rehearsal, changing a word or two every time. Each time it would alter very slightly, it would develop and evolve. 'When you talk about destruction...you can count me out.' 'When you talk about destruction...you can count me in.'” John either hadn't decided which way he felt or which way would be more palatable to his audience. Later that day, May 31st, 1968, The Beatles met up again at 2:30 pm at EMI Studios, this time in the smaller Studio Three. The first order of business was to perform overdubs onto the three open tracks of the four-track tape of "take 18." The first of these was John's lead vocals onto track two, accompanied by various electronic squeaks, presumably performed by Yoko. Technical engineer Alan Brown, new to EMI since November of 1967, was present on this day and remembers the rehearsals of this overdub. “I was in the control room of Studio Three and there on the other side of the glass was a figure in semi-darkness going over and over some lines of a song. I knew the voice and sure enough I knew the face. John Lennon was about 30 feet away! He was working on 'Revolution,' the slow one, and I remember him going through the song again and again in rehearsal, changing a word or two every time. Each time it would alter very slightly, it would develop and evolve. 'When you talk about destruction...you can count me out.' 'When you talk about destruction...you can count me in.'” John either hadn't decided which way he felt or which way would be more palatable to his audience.

John eventually decided to opt for both, singing "count me out...in" on this vocal performance, which was sung in a "light voice" in imitation of Martha Reeves and Diana Ross, as his handwritten lyric sheet reminded him. Then, when the main portion of the song was over, he decided to continue vocalizing to fill out the long rhythm track recorded the previous day. Regarding John's vocal performance in the latter half of the song, "The Beatles Recording Sessions" describe him as "repeatedly screaming 'alright' and then, simply, repeatedly screaming, with lots of on-microphone moaning by John and his new girlfriend Yoko Ono...the last six minutes would be hived off to form the basis for 'Revolution 9.'" Geoff Emerick's account of these vocal hijinks reveals that John was “spitting out the lyrics with barely restrained venom...He seemed to be trying to exorcise some inner demons, screaming the words 'all right' over and over again...By the end of it, his voice was shredded and he seemed exhausted. 'Okay, I've had enough,' he hoarsely instructed us up in the control room." The long rhythm track did continue on for another three minutes, however, after John's voice gave out. John eventually decided to opt for both, singing "count me out...in" on this vocal performance, which was sung in a "light voice" in imitation of Martha Reeves and Diana Ross, as his handwritten lyric sheet reminded him. Then, when the main portion of the song was over, he decided to continue vocalizing to fill out the long rhythm track recorded the previous day. Regarding John's vocal performance in the latter half of the song, "The Beatles Recording Sessions" describe him as "repeatedly screaming 'alright' and then, simply, repeatedly screaming, with lots of on-microphone moaning by John and his new girlfriend Yoko Ono...the last six minutes would be hived off to form the basis for 'Revolution 9.'" Geoff Emerick's account of these vocal hijinks reveals that John was “spitting out the lyrics with barely restrained venom...He seemed to be trying to exorcise some inner demons, screaming the words 'all right' over and over again...By the end of it, his voice was shredded and he seemed exhausted. 'Okay, I've had enough,' he hoarsely instructed us up in the control room." The long rhythm track did continue on for another three minutes, however, after John's voice gave out.

With this complete, John then double-tracked his lead vocals during the first portion of the song on track three of the four-track tape, adding a nearby Mellotron on the flute setting during the final minutes of the song while his vocal shenanigans had ended from his first vocal overdub. Onto track four of the tape was recorded Paul's bass, thus filling up all four tracks on the tape. Since the song had more elements that needed to be added, a tape reduction was made to open up more tracks, thus turning "take 18" into "take 19." The new tape now combined the acoustic guitar, piano, drums and bass on track one with both of John's vocal tracks combined on track four. Onto tracks two and three, John, Paul and George overdubbed their backing vocals, including their '50s-like “Shooby-doo, whop-bow” harmonies. At midnight the session was over and the group took the weekend off to refresh themselves and come up with other ideas for the song. With this complete, John then double-tracked his lead vocals during the first portion of the song on track three of the four-track tape, adding a nearby Mellotron on the flute setting during the final minutes of the song while his vocal shenanigans had ended from his first vocal overdub. Onto track four of the tape was recorded Paul's bass, thus filling up all four tracks on the tape. Since the song had more elements that needed to be added, a tape reduction was made to open up more tracks, thus turning "take 18" into "take 19." The new tape now combined the acoustic guitar, piano, drums and bass on track one with both of John's vocal tracks combined on track four. Onto tracks two and three, John, Paul and George overdubbed their backing vocals, including their '50s-like “Shooby-doo, whop-bow” harmonies. At midnight the session was over and the group took the weekend off to refresh themselves and come up with other ideas for the song.

June 4th, 1968 was the next Beatles recording session, this also beginning at 2:30 pm in EMI Studio Three. John was impressed enough with the rambling ten minute recording of the song as it was so far that his intentions were to add yet more overdubs to create an extensive sound collage as the first complete track for their next album. Not to be outdone by John, Paul also brought his new girlfriend Francie Schwartz to the studio on this day. At any rate, today's first order of business was for John to once again record lead vocals onto “Revolution,” as the song was still called. This vocal overdub was recorded onto track four of the tape for the first few minutes of the song, wiping out the double-tracked vocals that were there from the previous session but leaving the crazy vocalizations he made in the latter part of the song. June 4th, 1968 was the next Beatles recording session, this also beginning at 2:30 pm in EMI Studio Three. John was impressed enough with the rambling ten minute recording of the song as it was so far that his intentions were to add yet more overdubs to create an extensive sound collage as the first complete track for their next album. Not to be outdone by John, Paul also brought his new girlfriend Francie Schwartz to the studio on this day. At any rate, today's first order of business was for John to once again record lead vocals onto “Revolution,” as the song was still called. This vocal overdub was recorded onto track four of the tape for the first few minutes of the song, wiping out the double-tracked vocals that were there from the previous session but leaving the crazy vocalizations he made in the latter part of the song.

Technical engineer Brian Gibson remembers this overdub being recorded in a very odd manner. “John decided he would feel more comfortable on the floor so I had to rig up a microphone which would be suspended on a boom above his mouth. It struck me as somewhat odd, a little eccentric.” Many authors have suggested that this was done because John was too stoned to stand upright, but the actual evidence suggests otherwise. He was constantly suggesting as many different ways of recording his voice as possible, as he felt that his tonal delivery wasn't suitable, even though everyone around him tried their best to assure him otherwise. Throughout the Beatle years he would suggest things such as immersing his vocal microphone under water, positioning the mic behind his back, and even suspending himself from the rafters by his feet with a rope and spinning him while he sang (which was luckily never attempted). Laying down on the ground was just another of his ideas. “They were always looking for a different sound; something new,” Brian Gibson confirms. Technical engineer Brian Gibson remembers this overdub being recorded in a very odd manner. “John decided he would feel more comfortable on the floor so I had to rig up a microphone which would be suspended on a boom above his mouth. It struck me as somewhat odd, a little eccentric.” Many authors have suggested that this was done because John was too stoned to stand upright, but the actual evidence suggests otherwise. He was constantly suggesting as many different ways of recording his voice as possible, as he felt that his tonal delivery wasn't suitable, even though everyone around him tried their best to assure him otherwise. Throughout the Beatle years he would suggest things such as immersing his vocal microphone under water, positioning the mic behind his back, and even suspending himself from the rafters by his feet with a rope and spinning him while he sang (which was luckily never attempted). Laying down on the ground was just another of his ideas. “They were always looking for a different sound; something new,” Brian Gibson confirms.

There was a snag or two in the recording process, however. Engineer Peter Bown recalls: “Before we had new main cables laid to (EMI Studios), the volts used to go down pretty badly on a cold night and one evening in number three they went down so low that the stabilizers went on the four-track machine and made this awful sound in John Lennon's headphones while he was overdubbing. We fixed up another machine but about ten minutes later it happened again. I remember John coming into the control room saying, 'The f*cking machine has broken down again? It won't be the same when we get our own studio down at Apple (Studios)...' I replied 'Won't it?' and left it at that. He went out of the studio and sulked for a while, but at the end of the session poked his head around the door and said, 'I'm sorry, Pete, I realize it wasn't your fault.'” There was a snag or two in the recording process, however. Engineer Peter Bown recalls: “Before we had new main cables laid to (EMI Studios), the volts used to go down pretty badly on a cold night and one evening in number three they went down so low that the stabilizers went on the four-track machine and made this awful sound in John Lennon's headphones while he was overdubbing. We fixed up another machine but about ten minutes later it happened again. I remember John coming into the control room saying, 'The f*cking machine has broken down again? It won't be the same when we get our own studio down at Apple (Studios)...' I replied 'Won't it?' and left it at that. He went out of the studio and sulked for a while, but at the end of the session poked his head around the door and said, 'I'm sorry, Pete, I realize it wasn't your fault.'”

Once another tape reduction was made to open up more tracks, this now being called "take 20," more overdubs were performed. These included John double-tracking his "light voice" lead vocals for the first half of the song, Ringo adding some additional drums during the conclusion of each verse as well as some percussive clicking sounds elsewhere in the song, John on electric guitar using a volume pedal, and an organ part by Paul. Two tape loops were also created on this day, the purpose of which being to periodically pan them into the recording from time to time. One of these loops consisted of all four Beatles singing “Aaaaaaah” at a very high register, and the other loop was of what has been described as “a rather manic guitar phrase” which was a high A note played rapidly on an electric guitar. Once another tape reduction was made to open up more tracks, this now being called "take 20," more overdubs were performed. These included John double-tracking his "light voice" lead vocals for the first half of the song, Ringo adding some additional drums during the conclusion of each verse as well as some percussive clicking sounds elsewhere in the song, John on electric guitar using a volume pedal, and an organ part by Paul. Two tape loops were also created on this day, the purpose of which being to periodically pan them into the recording from time to time. One of these loops consisted of all four Beatles singing “Aaaaaaah” at a very high register, and the other loop was of what has been described as “a rather manic guitar phrase” which was a high A note played rapidly on an electric guitar.

Another strange vocal overdub was also made during this session, the tape box calling it “vocal backing mama papa,” which was an identification of strange vocal work from George, Paul, and Paul's girlfriend Francie Schwartz repeatedly singing “Mama / Dada / Mama / Dada / Mama / Dada” throughout the final minutes of the recording. The significance of this strange overdub has never been clarified, but in this case it may very well have been the result of being stoned! Another strange vocal overdub was also made during this session, the tape box calling it “vocal backing mama papa,” which was an identification of strange vocal work from George, Paul, and Paul's girlfriend Francie Schwartz repeatedly singing “Mama / Dada / Mama / Dada / Mama / Dada” throughout the final minutes of the recording. The significance of this strange overdub has never been clarified, but in this case it may very well have been the result of being stoned!

.jpg) After all of this was accomplished, an unnumbered rough mono mix was made for the song as it stood so far. The tape caught engineer Peter Bown announcing this remix as “rm1 of take...” and then pausing to identify which take this was. John then humorously fills in his hesitation with “take your knickers off and lets go...ha, ha.” The mix thus created was of the full ten minute version of the song with John's screaming in the second half being manually manipulated with tremelo and a wobbling effect, as well as the newly created tape loops being manually faded in and out from time to time from separate tape machines. Humorously, after Yoko's pre-recorded voice is heard saying "Maybe, it's not that" during the final moments of the mix, Paul replies in a highly exaggerated Liverpool accent, "It is that!" After all of this was accomplished, an unnumbered rough mono mix was made for the song as it stood so far. The tape caught engineer Peter Bown announcing this remix as “rm1 of take...” and then pausing to identify which take this was. John then humorously fills in his hesitation with “take your knickers off and lets go...ha, ha.” The mix thus created was of the full ten minute version of the song with John's screaming in the second half being manually manipulated with tremelo and a wobbling effect, as well as the newly created tape loops being manually faded in and out from time to time from separate tape machines. Humorously, after Yoko's pre-recorded voice is heard saying "Maybe, it's not that" during the final moments of the mix, Paul replies in a highly exaggerated Liverpool accent, "It is that!"

Incidentally, Yoko Ono had once again brought in her personal tape machine on this day to record herself speaking about her ambivilent feelings concerning being present in the studio with The Beatles as well as documenting her and John's relationship and sexual activities. In the background of this tape, which has been released on bootleg recordings, you can hear The Beatles extensively rehearsing as well as assembling this rough mix with George Martin and the engineering crew. Two copies of this mix were made, one of which was taken home by John on a plastic spool of tape, this also being readily available on bootleg releases. At 1 am the following morning, this strange session was finally completed. Incidentally, Yoko Ono had once again brought in her personal tape machine on this day to record herself speaking about her ambivilent feelings concerning being present in the studio with The Beatles as well as documenting her and John's relationship and sexual activities. In the background of this tape, which has been released on bootleg recordings, you can hear The Beatles extensively rehearsing as well as assembling this rough mix with George Martin and the engineering crew. Two copies of this mix were made, one of which was taken home by John on a plastic spool of tape, this also being readily available on bootleg releases. At 1 am the following morning, this strange session was finally completed.

In the next couple of days, a decision was made regarding this ten minute version of “Revolution.” John explains in his 1980 Playboy Magazine interview: “Well, the slow version of 'Revolution' on the album went on and on and on and I took the fade-out part, which is what they sometimes do with disco records now, and just layered all this stuff over it. It has the basic rhythm of the original 'Revolution' going on with some twenty loops we put on...It was a montage.” In the next couple of days, a decision was made regarding this ten minute version of “Revolution.” John explains in his 1980 Playboy Magazine interview: “Well, the slow version of 'Revolution' on the album went on and on and on and I took the fade-out part, which is what they sometimes do with disco records now, and just layered all this stuff over it. It has the basic rhythm of the original 'Revolution' going on with some twenty loops we put on...It was a montage.”

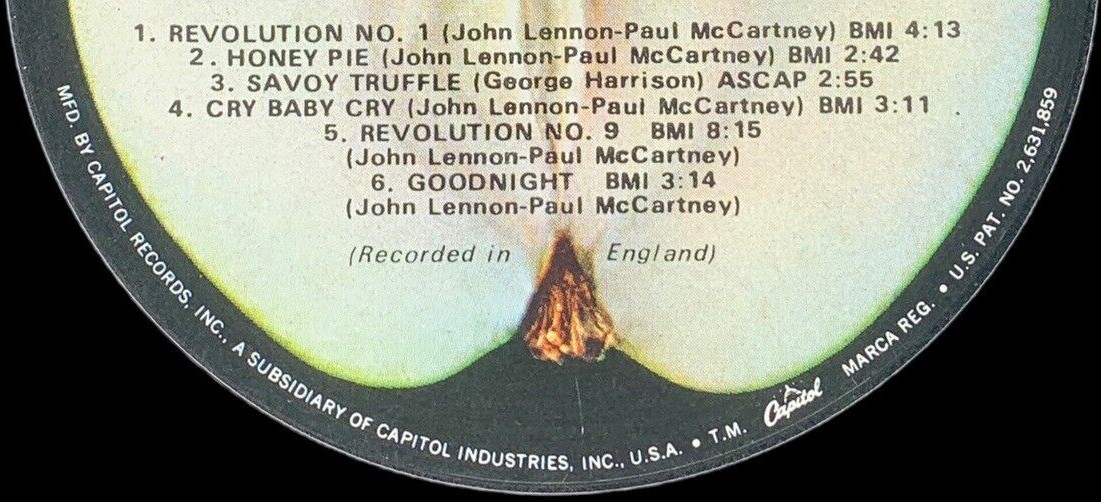

On June 6th, 1968, work began in earnest preparing tapes and loops of sound effects to be used in conjunction with the meandering second half of what they had recorded for “Revolution” thus far. Since it had been decided that this new “montage” track would be called “Revolution 9” because of the repeated voice “number nine” being heard throughout the track, it was now determined that the first half of the song would bear the title “Revolution 1." The two tape loops mentioned above, while not appearing on the released version of "Revolution 1," did get used when compiling "Revolution 9.” On June 6th, 1968, work began in earnest preparing tapes and loops of sound effects to be used in conjunction with the meandering second half of what they had recorded for “Revolution” thus far. Since it had been decided that this new “montage” track would be called “Revolution 9” because of the repeated voice “number nine” being heard throughout the track, it was now determined that the first half of the song would bear the title “Revolution 1." The two tape loops mentioned above, while not appearing on the released version of "Revolution 1," did get used when compiling "Revolution 9.”

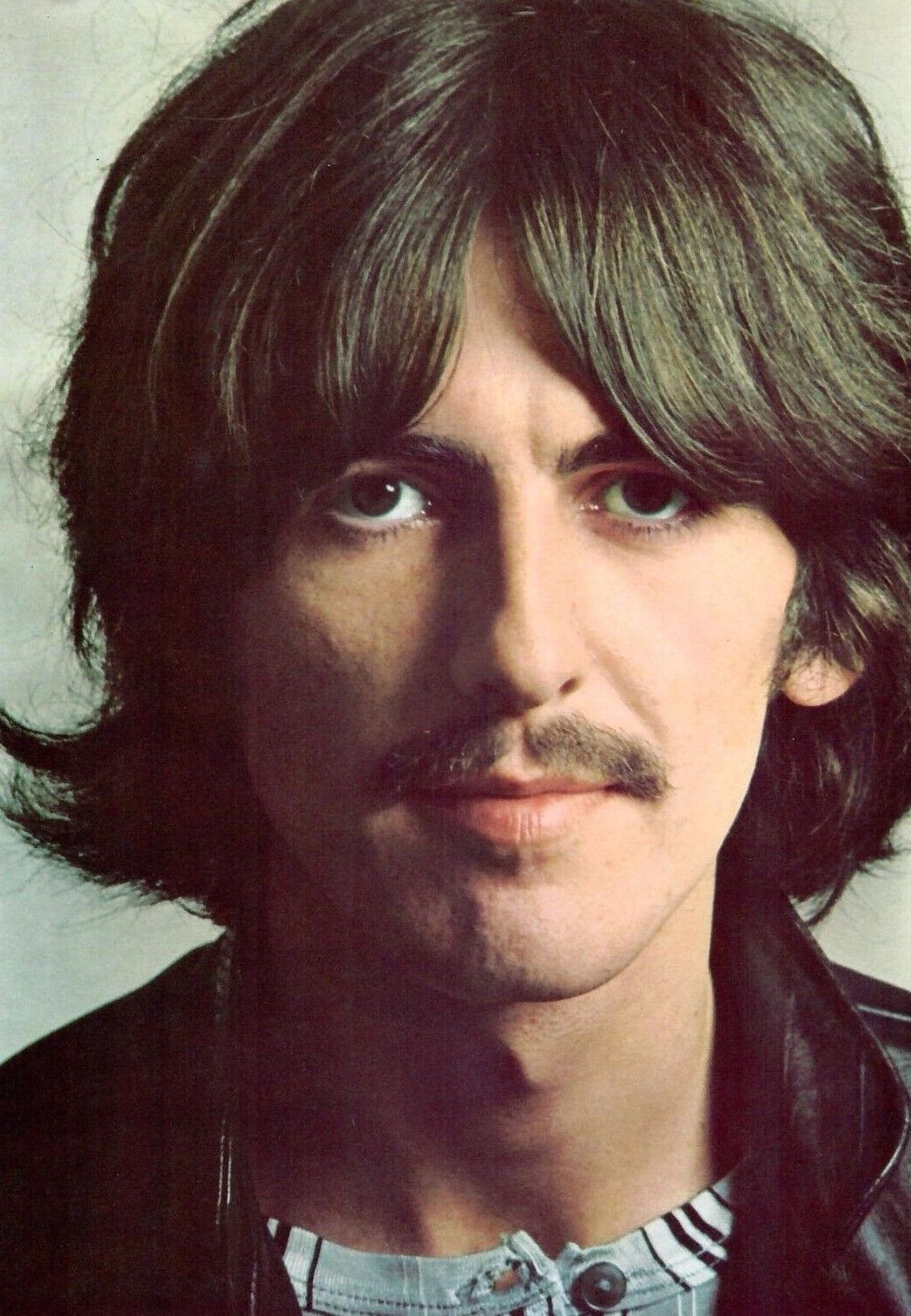

As for the first half of the song, more work was needed to get it to a finished state and ready for release as the next Beatles single. On June 21st, 1968, John and George entered EMI Studio Two at around 2:30 pm to put the finishing touches on the song. Neither Paul nor Ringo were present for this session, Paul being in the US at the time. As for the first half of the song, more work was needed to get it to a finished state and ready for release as the next Beatles single. On June 21st, 1968, John and George entered EMI Studio Two at around 2:30 pm to put the finishing touches on the song. Neither Paul nor Ringo were present for this session, Paul being in the US at the time.

The first thing on the agenda was overdubbing brass, something specially requested by John. He specifically wanted two tenor saxophones, a baritone sax, two trumpets and one trombone. However, he had to settle for two trumpets and four trombones, the session musicians arriving early at this session and playing from a score prepared in advance by George Martin. The first thing on the agenda was overdubbing brass, something specially requested by John. He specifically wanted two tenor saxophones, a baritone sax, two trumpets and one trombone. However, he had to settle for two trumpets and four trombones, the session musicians arriving early at this session and playing from a score prepared in advance by George Martin.

The brass overdub, which included Derek Watkins on trumpet, filled up the four tracks of the tape once again, so a reduction mix was again necessary, two attempts being made, turning "take 20" into "take 22." Onto this, one final overdub was needed; a lead guitar part played by George which included the distinctive opening riff played on distorted electric guitar in triplets. By 9 pm, this session was complete and an hour break ensued before a mixing session began at 10 pm. Seven stereo mixes of what was now called “Revolution 1” were made between 10 pm and midnight by George Martin and engineers Geoff Emerick and Richard Lush, with much input from John. Even though a lot of work was put into getting the best stereo mix, none of these ended up being used for the released record. After much work on creating a mix for “Revolution 9” occurred thereafter, this mixing session was over at 3:30 am the following morning. The brass overdub, which included Derek Watkins on trumpet, filled up the four tracks of the tape once again, so a reduction mix was again necessary, two attempts being made, turning "take 20" into "take 22." Onto this, one final overdub was needed; a lead guitar part played by George which included the distinctive opening riff played on distorted electric guitar in triplets. By 9 pm, this session was complete and an hour break ensued before a mixing session began at 10 pm. Seven stereo mixes of what was now called “Revolution 1” were made between 10 pm and midnight by George Martin and engineers Geoff Emerick and Richard Lush, with much input from John. Even though a lot of work was put into getting the best stereo mix, none of these ended up being used for the released record. After much work on creating a mix for “Revolution 9” occurred thereafter, this mixing session was over at 3:30 am the following morning.

The stereo mix of "Revolution 1" that did get used on the released album was made on June 25th, 1968 in the control room of EMI Studio Two by the same engineering team of George Martin, Geoff Emerick and Richard Lush with Lennon playing a hands-on role. During this session, which began at 2 pm, they attempted five more tries at getting a releasable stereo mix, "remix 12" being the keeper. Geoff Emerick, in “Here, There And Everywhere,” points out that having John as the only Beatle present during this mixing session “was quite unusual because, ever since the 'Pepper' days, all four Beatles normally attended even mixing sessions.” The stereo mix of "Revolution 1" that did get used on the released album was made on June 25th, 1968 in the control room of EMI Studio Two by the same engineering team of George Martin, Geoff Emerick and Richard Lush with Lennon playing a hands-on role. During this session, which began at 2 pm, they attempted five more tries at getting a releasable stereo mix, "remix 12" being the keeper. Geoff Emerick, in “Here, There And Everywhere,” points out that having John as the only Beatle present during this mixing session “was quite unusual because, ever since the 'Pepper' days, all four Beatles normally attended even mixing sessions.”

Geoff Emerick also points out a couple of other unique features to this mix, both of which were done at Lennon's suggestion. “There were two quirks that characterized that mix. One was an accidental bad edit in the last chorus, which Lennon insisted I leave in; it added an extra beat, and he always loved weird time signatures, so it was deemed a creative accident and it became part of the song." This mistake was actually then repeated at John's request, there being two extra beats on the released record. Geoff Emerick also points out a couple of other unique features to this mix, both of which were done at Lennon's suggestion. “There were two quirks that characterized that mix. One was an accidental bad edit in the last chorus, which Lennon insisted I leave in; it added an extra beat, and he always loved weird time signatures, so it was deemed a creative accident and it became part of the song." This mistake was actually then repeated at John's request, there being two extra beats on the released record.

"The other oddity about the final mix was that it featured my recording debut: that's my voice hurriedly saying 'Take two' just before the song begins. Because I always hated hearing my voice on tape, I had gotten in the habit of mumbling the slate as quickly as possible. John used to take the piss out of the way I rushed my announcements, so he left it in at the beginning of the song. It was done just to needle me, but at least it gave me the distinction of being one of only a few privileged outsiders who appear on a Beatles record!” (Mark Lewisohn describes this above as Geoff Emerick calling out "take 18" since this was the take that was used and not "take two." Some sources say Geoff Emerick is saying "I'll take it to..." on the talkback mic but cuts off his sentence because he realizes the "take" had already begun, John then answering "OK." While this all is debatable, Geoff Emerick's above recollection is the only eye-witness account we have in writing.) "The other oddity about the final mix was that it featured my recording debut: that's my voice hurriedly saying 'Take two' just before the song begins. Because I always hated hearing my voice on tape, I had gotten in the habit of mumbling the slate as quickly as possible. John used to take the piss out of the way I rushed my announcements, so he left it in at the beginning of the song. It was done just to needle me, but at least it gave me the distinction of being one of only a few privileged outsiders who appear on a Beatles record!” (Mark Lewisohn describes this above as Geoff Emerick calling out "take 18" since this was the take that was used and not "take two." Some sources say Geoff Emerick is saying "I'll take it to..." on the talkback mic but cuts off his sentence because he realizes the "take" had already begun, John then answering "OK." While this all is debatable, Geoff Emerick's above recollection is the only eye-witness account we have in writing.)

Before the session was over, a tape copy of this stereo mix was made and given to John for previewing to the other Beatles when the opportunity presented itself. The same was done for “Revolution 9,” this mixing session coming to a conclusion by 8 pm. It should be also be noted here that “Revolution 1” did not receive its own distinctive mono mix as did most other “White Album” songs. Instead, both channels of this stereo mix were combined for what was released as the mono version of the song. Before the session was over, a tape copy of this stereo mix was made and given to John for previewing to the other Beatles when the opportunity presented itself. The same was done for “Revolution 9,” this mixing session coming to a conclusion by 8 pm. It should be also be noted here that “Revolution 1” did not receive its own distinctive mono mix as did most other “White Album” songs. Instead, both channels of this stereo mix were combined for what was released as the mono version of the song.

At this point, “Revolution 1” was complete and ready for release as the next Beatles single. Or was it? “When George and Paul and all of them were on holiday,” Lennon explained in 1970, “I made (the mix of) 'Revolution (1)' which is on the LP. I wanted to put it out as a single, but they said it wasn't good enough. We put out 'Hey Jude,' which was worthy – but we could have had both.” John elaborated further in 1980: “The Beatles were getting real tense with each other. The first take, George and Paul were resentful and said it wasn't fast enough. Now, if you go into details of what a hit record is and isn't, maybe. But The Beatles could have afforded to put out the slow, understandable version of 'Revolution' as a single, whether it was a gold record or a wooden record. But, because they were so upset over the Yoko thing and the fact that I was again becoming as creative and dominating as I was in the early days, after lying fallow for a couple of years, it upset the applecart. I was awake again and they weren't used to it.” At this point, “Revolution 1” was complete and ready for release as the next Beatles single. Or was it? “When George and Paul and all of them were on holiday,” Lennon explained in 1970, “I made (the mix of) 'Revolution (1)' which is on the LP. I wanted to put it out as a single, but they said it wasn't good enough. We put out 'Hey Jude,' which was worthy – but we could have had both.” John elaborated further in 1980: “The Beatles were getting real tense with each other. The first take, George and Paul were resentful and said it wasn't fast enough. Now, if you go into details of what a hit record is and isn't, maybe. But The Beatles could have afforded to put out the slow, understandable version of 'Revolution' as a single, whether it was a gold record or a wooden record. But, because they were so upset over the Yoko thing and the fact that I was again becoming as creative and dominating as I was in the early days, after lying fallow for a couple of years, it upset the applecart. I was awake again and they weren't used to it.”

Therefore, in an effort to please the group, John took to re-recording the song in a heavier and more up-tempo fashion, the result being simply titled “Revolution.” Paul and George were apparently more pleased with this commercial version, it then appearing as the b-side of Paul's masterpiece “Hey Jude.” The a-side stayed at the #1 spot on the US Billboard Hot 100 for an astounding nine weeks, becoming what is considered the most popular Beatles song in America while John's b-side charted respectfully at #12 on the same chart, garnering a very healthy dose of radio airplay. Therefore, in an effort to please the group, John took to re-recording the song in a heavier and more up-tempo fashion, the result being simply titled “Revolution.” Paul and George were apparently more pleased with this commercial version, it then appearing as the b-side of Paul's masterpiece “Hey Jude.” The a-side stayed at the #1 spot on the US Billboard Hot 100 for an astounding nine weeks, becoming what is considered the most popular Beatles song in America while John's b-side charted respectfully at #12 on the same chart, garnering a very healthy dose of radio airplay.

Sometime in 2018, George Martin's son Giles Martin, along with engineer Sam Okell, returned to the master tapes of "Revolution 1" in order to make a vibrant new stereo mix of it for inclusion on the 50th Anniversary editions of the "White Album." They also created stereo mixes of both the Esher demo of the song they made on May 28th, 1968 and "take 18" from May 30th and 31st of that year. Sometime in 2018, George Martin's son Giles Martin, along with engineer Sam Okell, returned to the master tapes of "Revolution 1" in order to make a vibrant new stereo mix of it for inclusion on the 50th Anniversary editions of the "White Album." They also created stereo mixes of both the Esher demo of the song they made on May 28th, 1968 and "take 18" from May 30th and 31st of that year.

Song Structure and Style

The structure of “Revolution 1” is very straightforward, namely, 'verse/ chorus/ verse/ chorus/ verse/ chorus' (or ababab) with a simple introduction and faded conclusion added in. The song is presented with a slow swing-style beat in a 4/4 time signature but, as was Lennon's habit, he deviates this from time to time as we will see.

The fun The Beatles were having recording the rhythm track is decidedly preserved on the finished product, especially during its six measure introduction. The laughing and joking around by Paul and George would normally have been faded out of the mix but, in this case, it was captured by the microphones and couldn't be removed, a possible result of them thinking this introductory section was not going to be part of the finished product. Geoff Emerick's interruption of the proceedings, calling out the “slate” with John's acknowledgment of “OK,” was assuredly not intended to be heard on the released record, but John flippantly insisted. The fun The Beatles were having recording the rhythm track is decidedly preserved on the finished product, especially during its six measure introduction. The laughing and joking around by Paul and George would normally have been faded out of the mix but, in this case, it was captured by the microphones and couldn't be removed, a possible result of them thinking this introductory section was not going to be part of the finished product. Geoff Emerick's interruption of the proceedings, calling out the “slate” with John's acknowledgment of “OK,” was assuredly not intended to be heard on the released record, but John flippantly insisted.

The introduction consists of John on acoustic guitar and Ringo on drums, both from the rhythm track, as well as overdubs of John's iconic distorted lead guitar passage which appears in measures three through six and percussive noises (“washboard”?) in measures four through six. Just before the “washboard” is heard, a voice is heard instructing “Go on,” most probably John wanting this unconventional sound heard at the introduction of his song. The lead guitar is first heard in measure six as a suitable transition to the first verse that follows. The introduction consists of John on acoustic guitar and Ringo on drums, both from the rhythm track, as well as overdubs of John's iconic distorted lead guitar passage which appears in measures three through six and percussive noises (“washboard”?) in measures four through six. Just before the “washboard” is heard, a voice is heard instructing “Go on,” most probably John wanting this unconventional sound heard at the introduction of his song. The lead guitar is first heard in measure six as a suitable transition to the first verse that follows.