Search by Keyword

Sign Up Below for our MONTHLY BEATLES TRIVIA QUIZ!

|

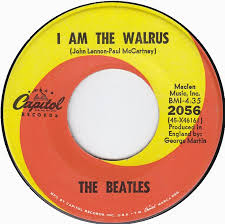

“I AM THE WALRUS”

(John Lennon – Paul McCartney)

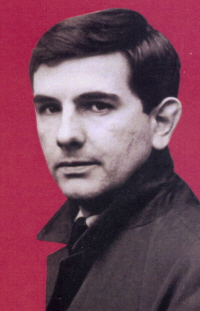

“Epstein (The Beatle-Making Prince Of Pop) Dies At 32.” So read the headline in Britain's “Daily Mirror” magazine in late August of 1967. Beatles manager Brian Epstein was found dead at his residence at 24 Chapel Street, London, on August 27th, 1967 of an accidental overdose of sleeping pills mixed with alcohol. “If anyone was the ‘fifth Beatle,’ it was Brian,” stated Paul McCartney. “Epstein (The Beatle-Making Prince Of Pop) Dies At 32.” So read the headline in Britain's “Daily Mirror” magazine in late August of 1967. Beatles manager Brian Epstein was found dead at his residence at 24 Chapel Street, London, on August 27th, 1967 of an accidental overdose of sleeping pills mixed with alcohol. “If anyone was the ‘fifth Beatle,’ it was Brian,” stated Paul McCartney.

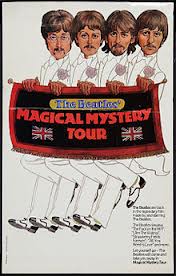

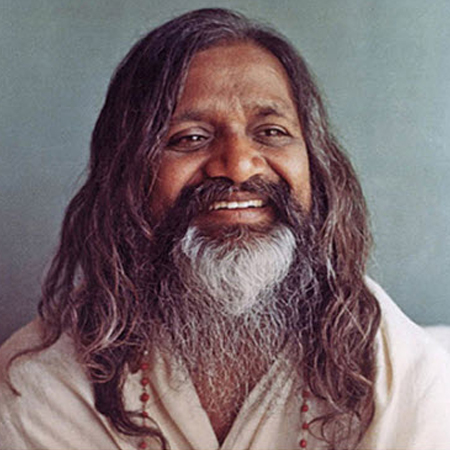

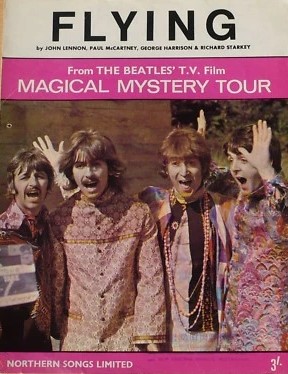

The Beatles were at a weekend retreat in Bangor, Wales listening to the teachings of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi during the time of Brian Epstein’s death. Upon hearing the bad news, “they cut their stay short and reconvened at McCartney’s house in St. John’s Wood on 1st September to decide what to do,” explained Ian MacDonald in his book “Revolution In The Head.” “McCartney knew that the psychological force that was holding them together would soon dissipate without some new creative focus, and argued that they must now get on with the ‘Magical Mystery Tour’ project. The others glumly agreed, John acquiescing despite seeing with his usual withering clarity that, without Epstein, The Beatles would soon fall apart.” The Beatles were at a weekend retreat in Bangor, Wales listening to the teachings of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi during the time of Brian Epstein’s death. Upon hearing the bad news, “they cut their stay short and reconvened at McCartney’s house in St. John’s Wood on 1st September to decide what to do,” explained Ian MacDonald in his book “Revolution In The Head.” “McCartney knew that the psychological force that was holding them together would soon dissipate without some new creative focus, and argued that they must now get on with the ‘Magical Mystery Tour’ project. The others glumly agreed, John acquiescing despite seeing with his usual withering clarity that, without Epstein, The Beatles would soon fall apart.”

With that decided, four days later the band entered EMI Studio One to carry on ‘business as usual,’ recording the recently composed Lennon song “I Am The Walrus.” This elaborate tour de force, therefore, has the distinction of being the first song The Beatles recorded after the death of their much-loved manager.

Songwriting History

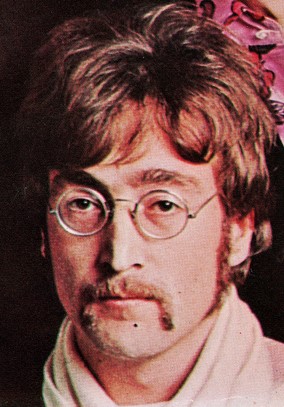

Writer Hunter Davies, who was spending a good amount of time individually and collectively with the band in order to put together the first official Beatles biography, remembers some interesting details regarding the inspiration to “I Am The Walrus” while with John at his Kenwood home, probably in late August, 1967.

“I remember being at John’s house in Weybridge, and we were swimming round the pool and, several streets away, you could hear a police siren going, ‘da-da, da-da, da-da, da-da,’ and John started humming this, and playing with those two notes. He actually got that on the piano, and they had a go at that, later that evening. They did a backing track and a few things.” Hunter Davies’ mention of having “a go at that, later that evening” as “a backing track” may have been referring to The Beatles experimenting with John’s idea in the recording studio, which could only have meant either August 22nd or 23rd, 1967, at Chappell Studios where they worked on Paul’s “Your Mother Should Know.” Since “I Am The Walrus” was nowhere near complete at this point, they certainly didn’t record an actual “backing track” on this day, evidenced also by it not being mentioned in any documentation. At best, John may have demonstrated his latest idea to the group on one of these days. “I remember being at John’s house in Weybridge, and we were swimming round the pool and, several streets away, you could hear a police siren going, ‘da-da, da-da, da-da, da-da,’ and John started humming this, and playing with those two notes. He actually got that on the piano, and they had a go at that, later that evening. They did a backing track and a few things.” Hunter Davies’ mention of having “a go at that, later that evening” as “a backing track” may have been referring to The Beatles experimenting with John’s idea in the recording studio, which could only have meant either August 22nd or 23rd, 1967, at Chappell Studios where they worked on Paul’s “Your Mother Should Know.” Since “I Am The Walrus” was nowhere near complete at this point, they certainly didn’t record an actual “backing track” on this day, evidenced also by it not being mentioned in any documentation. At best, John may have demonstrated his latest idea to the group on one of these days.

Elaborating further about the police siren inspiration on that day in his biography “The Beatles,” Hunter Davies continues: “The rhythm had stayed in his head and he was playing with putting words to it. ‘Mis-ter, Ci-ty, p’lice-man, sit-tin, pre-tty.’ He’d got as far as trying the words in a slightly different order – ‘Sitting pretty, like a policeman’ – but hadn’t got much further. He said it would be a basis for a song, but there was no need to develop it now. It could be dragged out next time he needed a song. ‘I’ve written in down on a piece of paper somewhere. I’m always sure I’ll forget it, so I write it down, but I wouldn’t.’” Elaborating further about the police siren inspiration on that day in his biography “The Beatles,” Hunter Davies continues: “The rhythm had stayed in his head and he was playing with putting words to it. ‘Mis-ter, Ci-ty, p’lice-man, sit-tin, pre-tty.’ He’d got as far as trying the words in a slightly different order – ‘Sitting pretty, like a policeman’ – but hadn’t got much further. He said it would be a basis for a song, but there was no need to develop it now. It could be dragged out next time he needed a song. ‘I’ve written in down on a piece of paper somewhere. I’m always sure I’ll forget it, so I write it down, but I wouldn’t.’”

“He’d written down another few words that day, just daft words, to put to another bit of rhythm. ‘Sitting on a cornflake, waiting for the man to come.’ I thought he said ‘van to come,’ which he hadn’t, but he liked it better and said he’d use it instead. He also had another piece of tune in his head. This had started from the phrase ‘sitting in an English country garden.’ This is what John does for at least two hours every day, sitting on the step outside his window looking at his garden. This time, thinking about himself doing it, he’d repeated the phrase over and over till he’d put a tune to it." “He’d written down another few words that day, just daft words, to put to another bit of rhythm. ‘Sitting on a cornflake, waiting for the man to come.’ I thought he said ‘van to come,’ which he hadn’t, but he liked it better and said he’d use it instead. He also had another piece of tune in his head. This had started from the phrase ‘sitting in an English country garden.’ This is what John does for at least two hours every day, sitting on the step outside his window looking at his garden. This time, thinking about himself doing it, he’d repeated the phrase over and over till he’d put a tune to it."

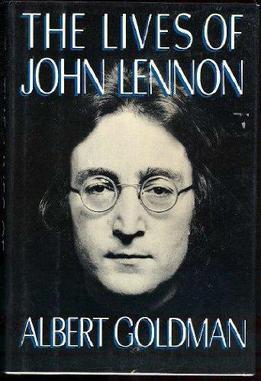

Quoting John on this day, Hunter Davies relates: “‘I don’t know how it will all end up. Perhaps, they’ll turn out to be different parts of the same song – sitting in an English country garden, waiting for the van to come. I don’t know.’ Which is what did happen. He put all the pieces together and made ‘I Am The Walrus.’ In the backing to the song can be heard the insistent rhythm of a police siren, which had sparked the song off in the first place. This very often happens. Bits of songs which have started off separately end up as one song when the time comes to empty his head and find a new song." In the book "The Lives Of John Lennon," author Albert Goldman states concerning the writing of "I Am The Walrus" that John "wrote the famous lyric by putting a sheet of paper into his typewriter and adding a line whenever the spirit moved him." Quoting John on this day, Hunter Davies relates: “‘I don’t know how it will all end up. Perhaps, they’ll turn out to be different parts of the same song – sitting in an English country garden, waiting for the van to come. I don’t know.’ Which is what did happen. He put all the pieces together and made ‘I Am The Walrus.’ In the backing to the song can be heard the insistent rhythm of a police siren, which had sparked the song off in the first place. This very often happens. Bits of songs which have started off separately end up as one song when the time comes to empty his head and find a new song." In the book "The Lives Of John Lennon," author Albert Goldman states concerning the writing of "I Am The Walrus" that John "wrote the famous lyric by putting a sheet of paper into his typewriter and adding a line whenever the spirit moved him."

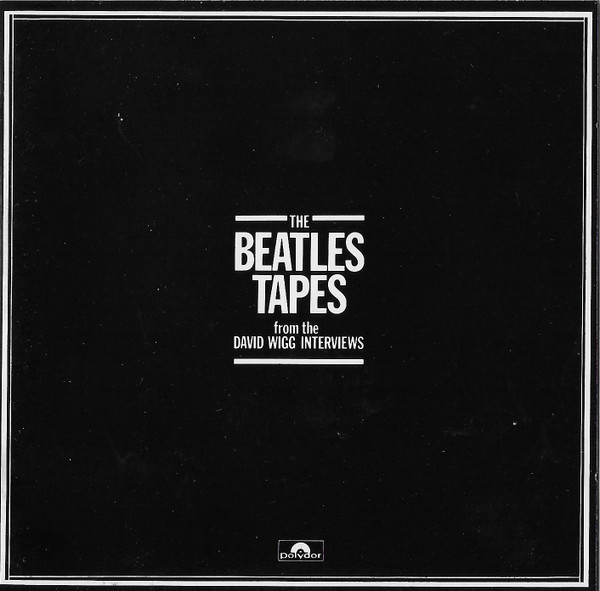

John gives some more details about the song’s writing in 1968: “We write lyrics, and I write lyrics that you don't realize what they mean till after. Especially some of the better songs or some of the more flowing ones, like 'Walrus.' The whole first verse was written without any knowledge. I didn’t know what I was saying, and you just find out later. I had 'I am he as you are he as we are all together.' I had just these two lines on the typewriter, and then about two weeks later I ran through and wrote another two lines and then, when I saw something, after about four lines, I just knocked the rest of it off. Then I had the whole verse, or verse and a half, and then sang it. I had this idea of doing a song that was a police siren, but it didn't work in the end (sings like a siren) 'I-am-he-as-you-are-he-as...' You couldn't really sing the police siren." It has been suggested that the folk song "Marching To Pretoria," popularized by The Weavers in 1963, may have been a subliminal inspiration for the first line of "I Am The Walrus." "Sing with me, I'll sing with you, and so we will sing together" is heard repeatedly in this song, as well as other similarly phrased lyrics that are sung in a somewhat similar cadence to John's "I am he as you are he" lyric. This, of course, has not been confirmed. John gives some more details about the song’s writing in 1968: “We write lyrics, and I write lyrics that you don't realize what they mean till after. Especially some of the better songs or some of the more flowing ones, like 'Walrus.' The whole first verse was written without any knowledge. I didn’t know what I was saying, and you just find out later. I had 'I am he as you are he as we are all together.' I had just these two lines on the typewriter, and then about two weeks later I ran through and wrote another two lines and then, when I saw something, after about four lines, I just knocked the rest of it off. Then I had the whole verse, or verse and a half, and then sang it. I had this idea of doing a song that was a police siren, but it didn't work in the end (sings like a siren) 'I-am-he-as-you-are-he-as...' You couldn't really sing the police siren." It has been suggested that the folk song "Marching To Pretoria," popularized by The Weavers in 1963, may have been a subliminal inspiration for the first line of "I Am The Walrus." "Sing with me, I'll sing with you, and so we will sing together" is heard repeatedly in this song, as well as other similarly phrased lyrics that are sung in a somewhat similar cadence to John's "I am he as you are he" lyric. This, of course, has not been confirmed.

To get an even clearer picture of the time frame, Lennon explains in his 1980 Playboy interview: “The first line was written on one acid trip one weekend. The second line was written on the next acid trip the next weekend, and it was filled in after I met Yoko.”

As for more information about the cryptic lyrics included in the song, the genesis of their origin is explained by long time friend Pete Shotton in his book “John Lennon In My Life.” The events described by Pete Shotton, as quoted below, must have taken place in late August of 1967. As for more information about the cryptic lyrics included in the song, the genesis of their origin is explained by long time friend Pete Shotton in his book “John Lennon In My Life.” The events described by Pete Shotton, as quoted below, must have taken place in late August of 1967.

"One afternoon, while taking ‘lucky dips’ into the day's sack of fan mail, John, much to both our amusement, chanced to pull out a letter from a student at Quarry Bank. Following the usual expressions of adoration, this lad revealed that his literature master was playing Beatles songs in class; after the boys all took their turns analyzing the lyrics, the teacher would weigh in with his own interpretation of what The Beatles were really talking about. (This, of course, was the same institution of learning whose headmaster had summed up young Lennon's prospects with the words: ‘This boy is bound to fail.’)” "One afternoon, while taking ‘lucky dips’ into the day's sack of fan mail, John, much to both our amusement, chanced to pull out a letter from a student at Quarry Bank. Following the usual expressions of adoration, this lad revealed that his literature master was playing Beatles songs in class; after the boys all took their turns analyzing the lyrics, the teacher would weigh in with his own interpretation of what The Beatles were really talking about. (This, of course, was the same institution of learning whose headmaster had summed up young Lennon's prospects with the words: ‘This boy is bound to fail.’)”

"John and I howled in laughter over the absurdity of it all. ‘Pete (Shotton),’ he said, ‘what's that “Dead Dog's Eye” song we used to sing when we were at Quarry Bank?’ I thought for a moment and it all came back to me: "John and I howled in laughter over the absurdity of it all. ‘Pete (Shotton),’ he said, ‘what's that “Dead Dog's Eye” song we used to sing when we were at Quarry Bank?’ I thought for a moment and it all came back to me:

‘Yellow matter custard, green slop pie, All mixed together with a dead dog's eye, Slap it on a butty, ten foot thick, Then wash it all down with a cup of cold sick.’

“‘That's it!’ said John. ‘Fantastic!’ He found a pen commenced scribbling: ‘Yellow matter custard dripping from a dead dog's eye....’”

“Inspired by the picture of that Quarry Bank literature master pontificating about the symbolism of Lennon - McCartney (songs), John threw in the most ludicrous images his imagination could conjure. He thought of ‘semolina’ (an insipid pudding we'd been forced to eat as kids) and ‘pilchard’ (a sardine we often fed to our cats). ‘Semolina pilchard, climbing up the Eiffel Tower....,’ John intoned, writing it down with considerable relish. He turned to me, smiling. ‘Let the f*ckers work THAT one out, Pete.’” “Inspired by the picture of that Quarry Bank literature master pontificating about the symbolism of Lennon - McCartney (songs), John threw in the most ludicrous images his imagination could conjure. He thought of ‘semolina’ (an insipid pudding we'd been forced to eat as kids) and ‘pilchard’ (a sardine we often fed to our cats). ‘Semolina pilchard, climbing up the Eiffel Tower....,’ John intoned, writing it down with considerable relish. He turned to me, smiling. ‘Let the f*ckers work THAT one out, Pete.’”

An interesting footnote to this account is that the sender of the original letter to John, Stephen Bayley, received a written answer in a letter from John dated September 1st, 1967. This answer letter, according to Steve Turner’s book “A Hard Day’s Write,” was “sold at auction by Christie’s of London in 1992.” An interesting footnote to this account is that the sender of the original letter to John, Stephen Bayley, received a written answer in a letter from John dated September 1st, 1967. This answer letter, according to Steve Turner’s book “A Hard Day’s Write,” was “sold at auction by Christie’s of London in 1992.”

As to the style of lyric writing used in the song, Lennon explained in 1980: “In those days I was writing obscurely, ala (Bob) Dylan, never saying what you mean but giving the impression of something, where more or less can be read into it. It’s a good game. I thought, ‘They get away with this artsy-fartsy crap.’ There has been more said about Dylan’s wonderful lyrics than was ever in the lyrics at all. Mine, too. But it was the intellectuals who read all this into Dylan or The Beatles. Dylan got away with murder. I thought, ‘I can write this crap, too.’ You just stick a few images together, thread them together, and you call it poetry. But I was just using the mind that wrote ‘In His Own Write’ to write that song.” As to the style of lyric writing used in the song, Lennon explained in 1980: “In those days I was writing obscurely, ala (Bob) Dylan, never saying what you mean but giving the impression of something, where more or less can be read into it. It’s a good game. I thought, ‘They get away with this artsy-fartsy crap.’ There has been more said about Dylan’s wonderful lyrics than was ever in the lyrics at all. Mine, too. But it was the intellectuals who read all this into Dylan or The Beatles. Dylan got away with murder. I thought, ‘I can write this crap, too.’ You just stick a few images together, thread them together, and you call it poetry. But I was just using the mind that wrote ‘In His Own Write’ to write that song.”

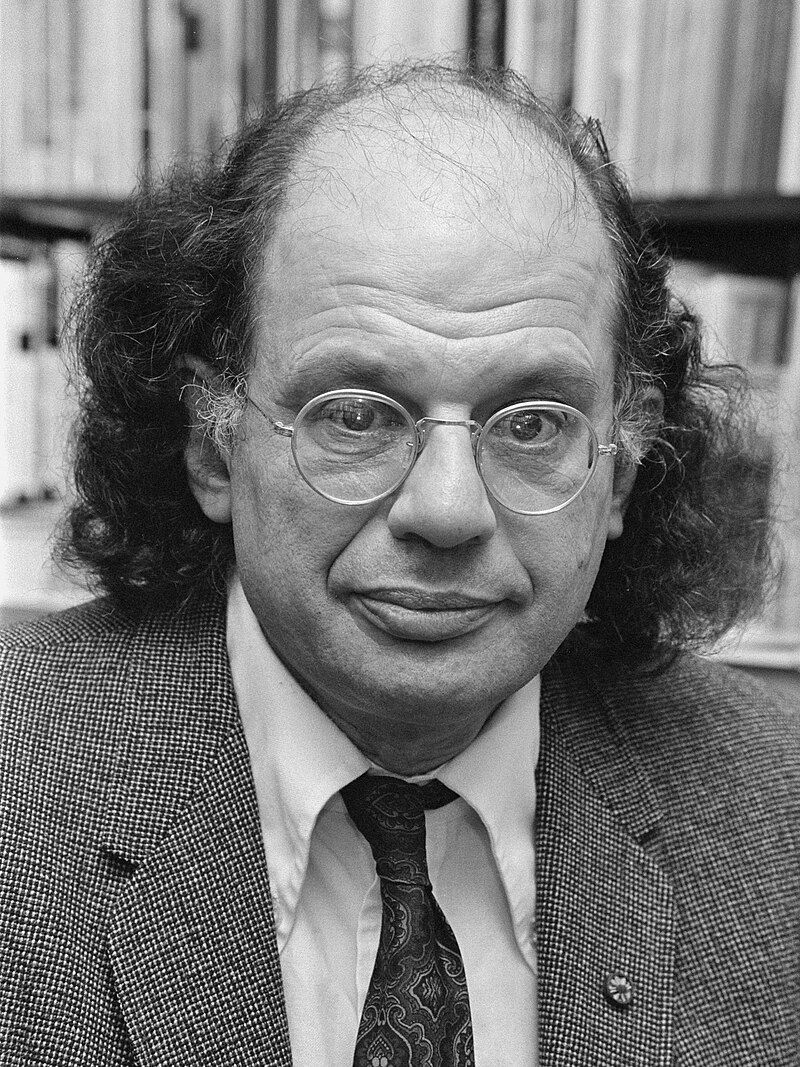

Lennon went into considerable detail during many interviews concerning the meaning behind various elements of the lyrics. “Part of it was putting down Hare Krishna,” John related to Playboy in 1980. “All these people were going on about Hare Krishna, Allen Ginsberg in particular. The reference to ‘Element’ry penguin’ is the elementary, naïve attitude of going around chanting, ‘Hare Krishna,’ or putting all your faith in any one idol.” Beat poet Allen Ginsberg, around this time, was performing recitals that, according to Ian MacDonald’s book “Revolution In The Head,” “chiefly consisted of him playing a harmonium and chanting mantras,” evidence of “the mechanical mantra-chanting of the ‘Hare Krishna’ movement.” Therefore, John took advantage of the occasion by putting in a slight dig at Ginsberg’s expense. Lennon went into considerable detail during many interviews concerning the meaning behind various elements of the lyrics. “Part of it was putting down Hare Krishna,” John related to Playboy in 1980. “All these people were going on about Hare Krishna, Allen Ginsberg in particular. The reference to ‘Element’ry penguin’ is the elementary, naïve attitude of going around chanting, ‘Hare Krishna,’ or putting all your faith in any one idol.” Beat poet Allen Ginsberg, around this time, was performing recitals that, according to Ian MacDonald’s book “Revolution In The Head,” “chiefly consisted of him playing a harmonium and chanting mantras,” evidence of “the mechanical mantra-chanting of the ‘Hare Krishna’ movement.” Therefore, John took advantage of the occasion by putting in a slight dig at Ginsberg’s expense.

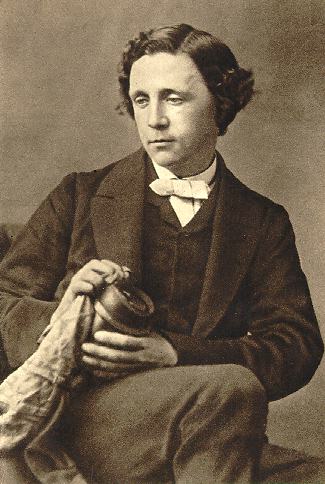

He also explained to Playboy: “The Walrus comes from ‘The Walrus And The Carpenter’; ‘Alice In Wonderland.’ To me, it was a beautiful poem. It never dawned on me that Lewis Carroll was commenting on the capitalist system. I never went into that bit about what he really meant, like people are doing with The Beatles’ work. Later I went back and looked at it and realized that the Walrus was the bad guy in the story, and the Carpenter was the good guy. I thought, ‘Oh, shit. I’ve picked the wrong guy.’ But that wouldn’t have been the same, would it? ‘I am the Carpenter…’” He also explained to Playboy: “The Walrus comes from ‘The Walrus And The Carpenter’; ‘Alice In Wonderland.’ To me, it was a beautiful poem. It never dawned on me that Lewis Carroll was commenting on the capitalist system. I never went into that bit about what he really meant, like people are doing with The Beatles’ work. Later I went back and looked at it and realized that the Walrus was the bad guy in the story, and the Carpenter was the good guy. I thought, ‘Oh, shit. I’ve picked the wrong guy.’ But that wouldn’t have been the same, would it? ‘I am the Carpenter…’”

Lennon expands on this a little more in a previous 1970 interview: “We saw the movie in LA, and the Walrus was a big capitalist that ate all the f*cking oysters. I always had the image of the Walrus in the garden and I loved it, and so I didn’t ever check what the Walrus was. He’s a f*cking bastard – that’s what he turns out to be. But the way it’s written, everybody presumes that means something. I mean, even I did. We all just presumed that because I said ‘I am the Walrus’ that it must mean ‘I am God’ or something. It’s just poetry, but it became symbolic of me.” Lennon expands on this a little more in a previous 1970 interview: “We saw the movie in LA, and the Walrus was a big capitalist that ate all the f*cking oysters. I always had the image of the Walrus in the garden and I loved it, and so I didn’t ever check what the Walrus was. He’s a f*cking bastard – that’s what he turns out to be. But the way it’s written, everybody presumes that means something. I mean, even I did. We all just presumed that because I said ‘I am the Walrus’ that it must mean ‘I am God’ or something. It’s just poetry, but it became symbolic of me.”

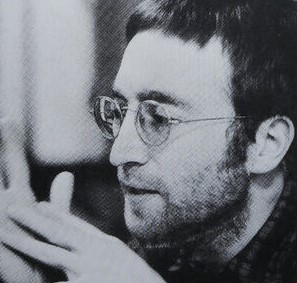

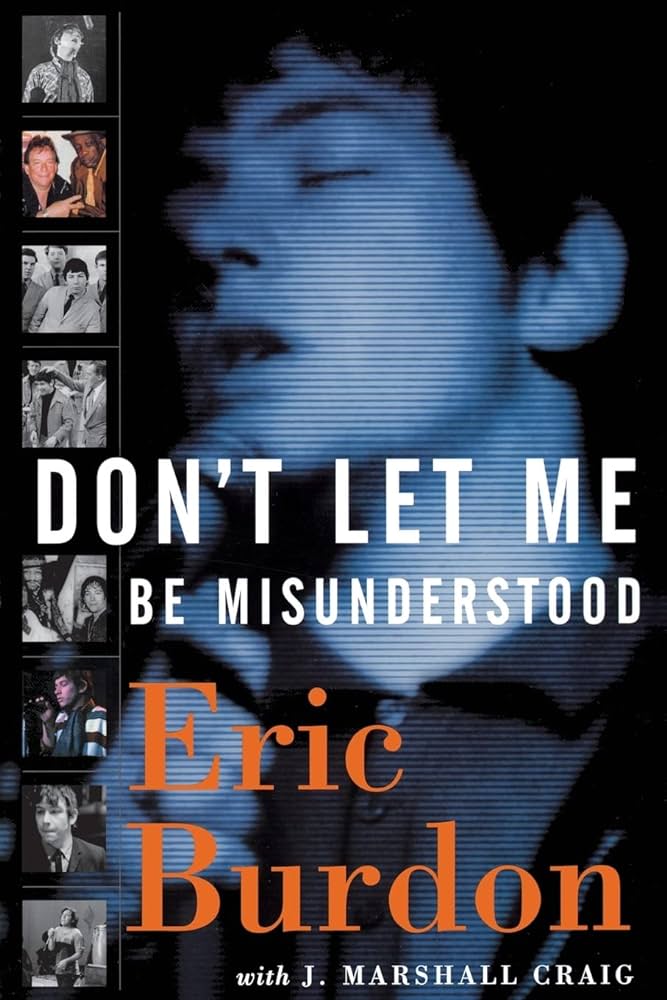

But what about the significance of the “egg man”? Eric Burdon, lead singer of the British group The Animals, reveals the identity of the “egg man” as himself in his autobiography “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood.” The event may be unsavory for some, but appears to have the ring of truth nonetheless. But what about the significance of the “egg man”? Eric Burdon, lead singer of the British group The Animals, reveals the identity of the “egg man” as himself in his autobiography “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood.” The event may be unsavory for some, but appears to have the ring of truth nonetheless.

Recalling his experiences with Lennon, Eric Burdon writes: “We had some great times together, something John gave a nod to in his song ‘I Am The Walrus.’ It may be one of my more dubious distinctions, but I was the ‘Egg Man,’ or, as some pals called me, ‘Eggs.’ The nickname stuck after a wild experience I’d had at the time with a Jamaican girlfriend named Sylvia. I was up early one morning cooking breakfast, naked except for my socks, and she slid up behind me and cracked an amyl nitrate capsule under my nose. As the fumes set my brain alight, and I slid to the kitchen floor, she reached to the counter and grabbed an egg, which she broke into the pit of my belly. The white and the yellow of the egg ran down my naked front and Sylvia…began to show me one Jamaican trick after another.”

Eric Burdon continues: “I shared the story with John at a party at a Mayfair flat one night with a handful of blondes and a little Asian girl. ‘Go on, go get it, Egg Man,’ Lennon laughed over the little round glasses perched on the end of his hooklike nose as we tried the all-too-willing girls on for size.” Eric Burdon continues: “I shared the story with John at a party at a Mayfair flat one night with a handful of blondes and a little Asian girl. ‘Go on, go get it, Egg Man,’ Lennon laughed over the little round glasses perched on the end of his hooklike nose as we tried the all-too-willing girls on for size.”

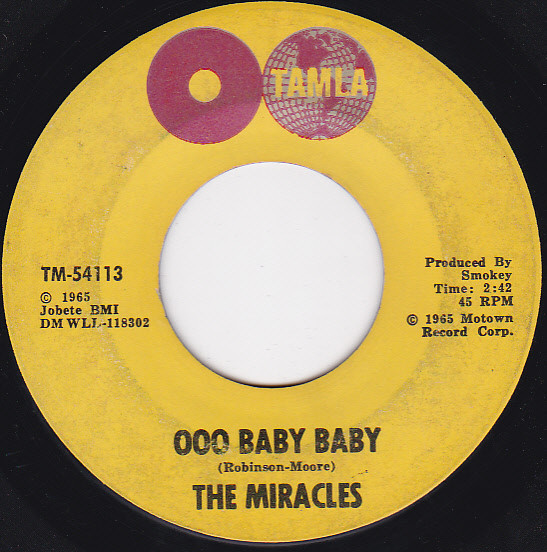

Also interesting is the six-times repeated phrase “I’m crying,” which is heard periodically at the end of verses. It appears more than coincidental that this same phrase is heard, sung in the same way, at the end of each verse on the Smokey Robinson And The Miracles song “Ooo Baby Baby,” which was a hit in the early summer of 1965. “Smokey Robinson was like God in our eyes,” McCartney once exclaimed, Lennon even admitting once to Yoko that he was always “trying to do Smokey Robinson” during The Beatles’ years. Also interesting is the six-times repeated phrase “I’m crying,” which is heard periodically at the end of verses. It appears more than coincidental that this same phrase is heard, sung in the same way, at the end of each verse on the Smokey Robinson And The Miracles song “Ooo Baby Baby,” which was a hit in the early summer of 1965. “Smokey Robinson was like God in our eyes,” McCartney once exclaimed, Lennon even admitting once to Yoko that he was always “trying to do Smokey Robinson” during The Beatles’ years.

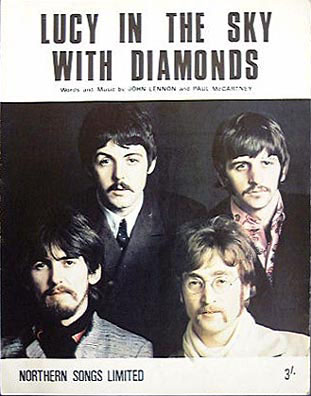

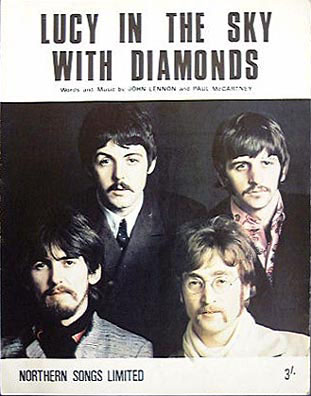

A reference to the song “Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds,” which was by then assumed by most writers and fans as referring to LSD, got a quick mention in the lyrics to “I Am The Walrus.” “See how they fly like lucy in the sky” may very well have been a nod of acknowledgement to these drug related assumptions which were being adamantly denied by the group. From this point forward, it became somewhat more common in The Beatles catalog to refer to lyrics of previously recorded songs, the Walrus lyric “see how they run” appearing in “Lady Madonna” as well as the obvious Walrus references in “Glass Onion.” A reference to the song “Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds,” which was by then assumed by most writers and fans as referring to LSD, got a quick mention in the lyrics to “I Am The Walrus.” “See how they fly like lucy in the sky” may very well have been a nod of acknowledgement to these drug related assumptions which were being adamantly denied by the group. From this point forward, it became somewhat more common in The Beatles catalog to refer to lyrics of previously recorded songs, the Walrus lyric “see how they run” appearing in “Lady Madonna” as well as the obvious Walrus references in “Glass Onion.”

Another curious lyrical inclusion in “I Am The Walrus,” one that got the song banned by the BBC, was the phrase, “You’ve been a naughty girl, you’ve let your knickers down.” "Everyone keeps preaching that the best way is to be 'open' when writing for teenagers,” Paul stated in 1967. “Then when we do we get criticized, surely the word 'knickers' can't offend anyone. Shakespeare wrote words a lot more naughtier than knickers!" John passively added, “We chose the word (knickers) because it is a lovely expressive word. It rolls off the tongue. It could 'mean' anything." Another curious lyrical inclusion in “I Am The Walrus,” one that got the song banned by the BBC, was the phrase, “You’ve been a naughty girl, you’ve let your knickers down.” "Everyone keeps preaching that the best way is to be 'open' when writing for teenagers,” Paul stated in 1967. “Then when we do we get criticized, surely the word 'knickers' can't offend anyone. Shakespeare wrote words a lot more naughtier than knickers!" John passively added, “We chose the word (knickers) because it is a lovely expressive word. It rolls off the tongue. It could 'mean' anything."

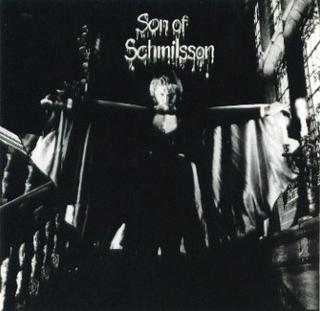

In Hunter Davies "Beatles" biography, George Harrison relates his opinion about how people take Beatles lyrics too seriously. "That's what people don't understand," he states, adding: "like John's 'I Am The Walrus' - 'I am he as you are he as you are me.' That's true but it's still a joke. People looked for all sorts of hidden meanings. It's serious and it's not serious." After expressing his approval of Lennon's use of the word "knickers," he stated: "Why can't you have people f*cking as well: It's going on everywhere in the world, all the time. So why can't you mention it? It's just a word made up by people. It's meaningless in itself. Keep saying it - F*ck, f*ck, f*ck, f*ck, f*ck, f*ck, f*ck. See, it doesn't mean a thing, so why can't you use it in a song? We will eventually. We haven't started yet." Of course, the following year they hinted at it with Paul's "Why Don't We Do It In The Road," but I think we can all agree that the Beatles' legacy is much better off for them not having gone there fully. Lennon did cross that line in "Working Class Hero" in 1970 after the band's breakup, but otherwise they left that to, among others, their pal Harry Nilsson in 1972 with his song "You're Breaking My Heart" as featured on his album "Son Of Schmilsson." In Hunter Davies "Beatles" biography, George Harrison relates his opinion about how people take Beatles lyrics too seriously. "That's what people don't understand," he states, adding: "like John's 'I Am The Walrus' - 'I am he as you are he as you are me.' That's true but it's still a joke. People looked for all sorts of hidden meanings. It's serious and it's not serious." After expressing his approval of Lennon's use of the word "knickers," he stated: "Why can't you have people f*cking as well: It's going on everywhere in the world, all the time. So why can't you mention it? It's just a word made up by people. It's meaningless in itself. Keep saying it - F*ck, f*ck, f*ck, f*ck, f*ck, f*ck, f*ck. See, it doesn't mean a thing, so why can't you use it in a song? We will eventually. We haven't started yet." Of course, the following year they hinted at it with Paul's "Why Don't We Do It In The Road," but I think we can all agree that the Beatles' legacy is much better off for them not having gone there fully. Lennon did cross that line in "Working Class Hero" in 1970 after the band's breakup, but otherwise they left that to, among others, their pal Harry Nilsson in 1972 with his song "You're Breaking My Heart" as featured on his album "Son Of Schmilsson."

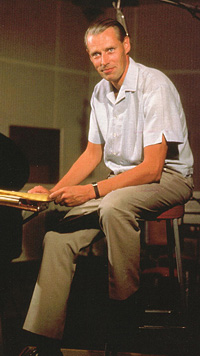

An interesting observation of John and Paul's individual songwriting style was detailed by producer George Martin in Hunter Davies' "Beatles" biography. Regarding Paul, George Martin stated: "He's the sort of Rodgers and Hart of the two...All the time he's trying to do better, especially trying to equal John's talent for words. Meeting John has made him try for deeper lyrics...John writes for his own amusement. He would be content to play his tunes to (his wife) Cyn. Paul likes a public. John's concept of music is very interesting. I was once playing Ravel's 'Daphnis and Chloe' to him. He said he couldn't grasp it because the melodic lines were too long. He said he looked upon writing music as doing little bits which you then join up. This does seem to be true, judging by the way John has written many of his songs, such as 'I Am The Walrus.'" The detailed lyrical explanations outlined above testify to this. An interesting observation of John and Paul's individual songwriting style was detailed by producer George Martin in Hunter Davies' "Beatles" biography. Regarding Paul, George Martin stated: "He's the sort of Rodgers and Hart of the two...All the time he's trying to do better, especially trying to equal John's talent for words. Meeting John has made him try for deeper lyrics...John writes for his own amusement. He would be content to play his tunes to (his wife) Cyn. Paul likes a public. John's concept of music is very interesting. I was once playing Ravel's 'Daphnis and Chloe' to him. He said he couldn't grasp it because the melodic lines were too long. He said he looked upon writing music as doing little bits which you then join up. This does seem to be true, judging by the way John has written many of his songs, such as 'I Am The Walrus.'" The detailed lyrical explanations outlined above testify to this.

Another interesting tidbit concerning the lyrics of this song is that George Harrison, in a 1968 interview conducted while in India studying Transcendental Meditation with the Maharishi, told journalist Lewis Lapham that John incorporated the personal mantra he was given by the guru the previous year into the lyrics of "I Am The Walrus." It was sometime between August 24th, 1967 when The Beatles first met with the Maharishi in London and when they met with him in Bangor, North Wales August 25th through the 27th that Lennon would have received his mantra. When given a mantra to use in meditation, it was to be kept secret and never revealed to anyone, only to be used personally. Knowing Lennon's personality, it only makes sense that he would dare to secretly reveal the mantra in the lyrics to a song, although we can only speculate what the mantra actually was. Could it possibly have been within the phrase "goo-goo-g'joob"? I think we can rightly assume it didn't include the word "knickers." Another interesting tidbit concerning the lyrics of this song is that George Harrison, in a 1968 interview conducted while in India studying Transcendental Meditation with the Maharishi, told journalist Lewis Lapham that John incorporated the personal mantra he was given by the guru the previous year into the lyrics of "I Am The Walrus." It was sometime between August 24th, 1967 when The Beatles first met with the Maharishi in London and when they met with him in Bangor, North Wales August 25th through the 27th that Lennon would have received his mantra. When given a mantra to use in meditation, it was to be kept secret and never revealed to anyone, only to be used personally. Knowing Lennon's personality, it only makes sense that he would dare to secretly reveal the mantra in the lyrics to a song, although we can only speculate what the mantra actually was. Could it possibly have been within the phrase "goo-goo-g'joob"? I think we can rightly assume it didn't include the word "knickers."

To put it all in a nutshell, Lennon explained in 1969, “’Walrus’ is just saying a dream – the words don’t mean a lot. People draw so many conclusions and it’s ridiculous.” He added in 1980: “I’ve had tongue in cheek all along – all of them had tongue in cheek. Just because other people see depths of whatever in it…What does it really mean, ‘I am the eggman’? It could have been ‘the pudding basin,’ for all I care. It’s not that serious.” To put it all in a nutshell, Lennon explained in 1969, “’Walrus’ is just saying a dream – the words don’t mean a lot. People draw so many conclusions and it’s ridiculous.” He added in 1980: “I’ve had tongue in cheek all along – all of them had tongue in cheek. Just because other people see depths of whatever in it…What does it really mean, ‘I am the eggman’? It could have been ‘the pudding basin,’ for all I care. It’s not that serious.”

Recording History

“All four Beatles met up at Paul’s St. John’s Wood house on 1 September (1967), four days after the death of Brian Epstein,” stated Mark Lewisohn in his 1988 book “The Beatles Recording Sessions.” “They decided on many things, one of them being to press on with the ‘Magical Mystery Tour’ project, the band temporarily postponing a planned visit to India for studying Transcendental Meditation.” Four days after this, on September 5th, 1967, they arrived at EMI Studio One at around 7 pm to start on their first new song since the death of their esteemed manager, John’s composition “I Am The Walrus.” “All four Beatles met up at Paul’s St. John’s Wood house on 1 September (1967), four days after the death of Brian Epstein,” stated Mark Lewisohn in his 1988 book “The Beatles Recording Sessions.” “They decided on many things, one of them being to press on with the ‘Magical Mystery Tour’ project, the band temporarily postponing a planned visit to India for studying Transcendental Meditation.” Four days after this, on September 5th, 1967, they arrived at EMI Studio One at around 7 pm to start on their first new song since the death of their esteemed manager, John’s composition “I Am The Walrus.”

Engineer Geoff Emerick, in his book “Here, There And Everywhere,” remembered the events of this recording session, including when John first debuted this song. “There was a pallor across the session that day – we were all distracted, thinking about Brian – but there was a song to be recorded, too. It was one of John’s, and, somewhat fittingly, it might well have been his strangest one yet. ‘I am he as you are he / As you are me and we are all together,’ Lennon sang in a dull monotone, strumming his acoustic guitar as we all gathered around him in the dim studio light. We all seemed bewildered. The melody consisted largely of just two notes, and these lyrics were pretty much just nonsense, for some reason Lennon appeared to be singing about a walrus and an eggman. There was a moment of silence when he finished, then Lennon looked up at George Martin expectantly.” Engineer Geoff Emerick, in his book “Here, There And Everywhere,” remembered the events of this recording session, including when John first debuted this song. “There was a pallor across the session that day – we were all distracted, thinking about Brian – but there was a song to be recorded, too. It was one of John’s, and, somewhat fittingly, it might well have been his strangest one yet. ‘I am he as you are he / As you are me and we are all together,’ Lennon sang in a dull monotone, strumming his acoustic guitar as we all gathered around him in the dim studio light. We all seemed bewildered. The melody consisted largely of just two notes, and these lyrics were pretty much just nonsense, for some reason Lennon appeared to be singing about a walrus and an eggman. There was a moment of silence when he finished, then Lennon looked up at George Martin expectantly.”

“’That one was called ‘I Am The Walrus,’ John said, ‘So…what do you think?’ George (Martin) looked flummoxed. For once he was at a loss for words. ‘Well, John, to be honest, I have only one question: What the hell do you expect me to do with that?’” “’That one was called ‘I Am The Walrus,’ John said, ‘So…what do you think?’ George (Martin) looked flummoxed. For once he was at a loss for words. ‘Well, John, to be honest, I have only one question: What the hell do you expect me to do with that?’”

“There was a round of nervous laughter in the room which partially dissipated the tension, but Lennon was clearly not amused. Frankly, I thought George’s remark was out of line. To me, The Beatles seemed a bit lost, as if they were looking for another place to be, a new start…and even in its raw state I could hear that the song had potential. Perhaps it wasn’t one of John’s finest compositional efforts, but with that unique voice of his and our combined creative abilities, I was sure it could turn into something good.”

"George Martin, however, simply could not get past the limited musical content and outrageous lyrics; he flat out did not like the song. As Lennon sang provocative lines about a pornographic priestess and letting knickers down, George turned to me and whispered, ‘What did he just say?’ He couldn’t believe his ears, and after the experience The Beatles had gone through with ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’ and ‘A Day In The Life,’ I guess he was worried about more censorship problems from the BBC.” "George Martin, however, simply could not get past the limited musical content and outrageous lyrics; he flat out did not like the song. As Lennon sang provocative lines about a pornographic priestess and letting knickers down, George turned to me and whispered, ‘What did he just say?’ He couldn’t believe his ears, and after the experience The Beatles had gone through with ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’ and ‘A Day In The Life,’ I guess he was worried about more censorship problems from the BBC.”

"Despite George’s misgivings, The Beatles were determined to work on this song, so the band began running down the backing track, with Lennon accompanying himself, unusually, on a Wurlitzer electric piano. He was not a great keyboardist at the best of times, and on this day he was especially unfocused, so he made quite a few fluffs, to George Martin’s chagrin. ‘Why doesn’t he ask Paul to play it instead?’ he asked me in the control room.” (Andy Babiuk’s book “Beatles Gear” cites the keyboard John used as a Hohner Pianet, not a Wurlitzer electric piano.) "Despite George’s misgivings, The Beatles were determined to work on this song, so the band began running down the backing track, with Lennon accompanying himself, unusually, on a Wurlitzer electric piano. He was not a great keyboardist at the best of times, and on this day he was especially unfocused, so he made quite a few fluffs, to George Martin’s chagrin. ‘Why doesn’t he ask Paul to play it instead?’ he asked me in the control room.” (Andy Babiuk’s book “Beatles Gear” cites the keyboard John used as a Hohner Pianet, not a Wurlitzer electric piano.)

"I had no answer; perhaps John was just attempting to get his grief out. George (Martin) became even more exasperated when it became apparent that Ringo was having trouble holding the beat steady; it was a long song, played at a laconic tempo, so it was tough going. For the first few takes, Paul played bass as usual, but then he opted to switch to tambourine, standing directly in front of Ringo, effectively acting as both a cheerleader and a human click track.” "I had no answer; perhaps John was just attempting to get his grief out. George (Martin) became even more exasperated when it became apparent that Ringo was having trouble holding the beat steady; it was a long song, played at a laconic tempo, so it was tough going. For the first few takes, Paul played bass as usual, but then he opted to switch to tambourine, standing directly in front of Ringo, effectively acting as both a cheerleader and a human click track.”

“’Not to worry, I will keep you locked in,’ he told his drummer confidently, once again dealing with a tricky situation that George Martin simply couldn’t handle. I thought it was one of Paul’s finest moments. He was trying to interject some professionalism into a session that was drifting away because the others had their minds on Brian (Epstein)’s death. It was a classic case of him taking charge when things were beginning to unravel, and he would do that more and more as the years went on.” “’Not to worry, I will keep you locked in,’ he told his drummer confidently, once again dealing with a tricky situation that George Martin simply couldn’t handle. I thought it was one of Paul’s finest moments. He was trying to interject some professionalism into a session that was drifting away because the others had their minds on Brian (Epstein)’s death. It was a classic case of him taking charge when things were beginning to unravel, and he would do that more and more as the years went on.”

“In the end, Ringo gave a strong performance, thanks in no small part to Paul’s quick thinking; Paul always did have the most rock-solid sense of timing in the band, and Ringo had the humility to be able to accept his help when it was needed. But even listening to the record today you can hear that they’re distracted, that their minds are not really on what they were doing. I distinctly remember the look of emptiness on all their faces while they were playing ‘I Am The Walrus.’ It’s one of the saddest memories I have of my time with The Beatles.” “In the end, Ringo gave a strong performance, thanks in no small part to Paul’s quick thinking; Paul always did have the most rock-solid sense of timing in the band, and Ringo had the humility to be able to accept his help when it was needed. But even listening to the record today you can hear that they’re distracted, that their minds are not really on what they were doing. I distinctly remember the look of emptiness on all their faces while they were playing ‘I Am The Walrus.’ It’s one of the saddest memories I have of my time with The Beatles.”

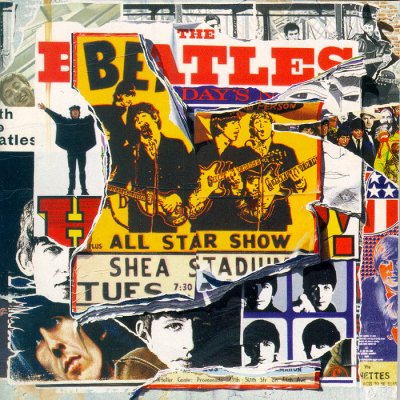

This six-hour recording session resulted in 16 takes of the rhythm track being recorded, the first three takes being recorded over as the tape was rewound to begin "take four." The instrumentation comprised Lennon on electric piano, George on electric rhythm guitar, Ringo on drums and Paul, having abandoned his bass guitar after the first few takes, delivered a steady tambourine beat. No vocals were recorded for the song at this point. "Take 16" was deemed the best and was set aside for overdubs to be recorded the following day. The book “The Beatles Recording Sessions” stipulates “an overdub of a mellotron” was added on this day, but no evidence of this instrument can be witnessed on the existing “take 16” as featured on the 1996 album “Anthology 2.” Either it was mixed out of the recording or the “Recording Sessions” book was mistaken. This six-hour recording session resulted in 16 takes of the rhythm track being recorded, the first three takes being recorded over as the tape was rewound to begin "take four." The instrumentation comprised Lennon on electric piano, George on electric rhythm guitar, Ringo on drums and Paul, having abandoned his bass guitar after the first few takes, delivered a steady tambourine beat. No vocals were recorded for the song at this point. "Take 16" was deemed the best and was set aside for overdubs to be recorded the following day. The book “The Beatles Recording Sessions” stipulates “an overdub of a mellotron” was added on this day, but no evidence of this instrument can be witnessed on the existing “take 16” as featured on the 1996 album “Anthology 2.” Either it was mixed out of the recording or the “Recording Sessions” book was mistaken.

On the following day, September 6th, 1967, The Beatles assembled in EMI Studio Two for more work on “I Am The Walrus.” Sometime around 7 pm the session started with a tape reduction of the previous day's "take 16" being made, this opening up additional tracks for overdubs. This made the recording "take 17," onto which Paul recorded his bass guitar and Ringo added more drums. On the following day, September 6th, 1967, The Beatles assembled in EMI Studio Two for more work on “I Am The Walrus.” Sometime around 7 pm the session started with a tape reduction of the previous day's "take 16" being made, this opening up additional tracks for overdubs. This made the recording "take 17," onto which Paul recorded his bass guitar and Ringo added more drums.

Another overdub added this day was John’s breath-taking lead vocal track. Geoff Emerick explained: "I always felt that John Lennon hid some of his insecurities behind his vocal disguises and nonsense wordplay. On this occassion, he informed us that he wanted his voice to appear to be coming from the moon. I had no idea what a man on the moon might sound like – or even what John was really hearing in his head – but, as usual, no amount of discussion with him could shed a lot of light on the matter. After a little bit of thought, I ended up overloading the console’s mic preamps so as to get a smooth, round kind of distortion – something that was, once again, in clear violation of EMI’s strict rules. To make his voice sound even edgier, I used a cheap low-fidelity talkback microphone." Another overdub added this day was John’s breath-taking lead vocal track. Geoff Emerick explained: "I always felt that John Lennon hid some of his insecurities behind his vocal disguises and nonsense wordplay. On this occassion, he informed us that he wanted his voice to appear to be coming from the moon. I had no idea what a man on the moon might sound like – or even what John was really hearing in his head – but, as usual, no amount of discussion with him could shed a lot of light on the matter. After a little bit of thought, I ended up overloading the console’s mic preamps so as to get a smooth, round kind of distortion – something that was, once again, in clear violation of EMI’s strict rules. To make his voice sound even edgier, I used a cheap low-fidelity talkback microphone."

"Even then, John wasn’t entirely happy with the result but, as usual, he was also impatient to get on with it. ‘Okay, that will do,’ he said abruptly after a brief run-through," exclaiming to assistant Mal Evans (as quietly heard on "Anthology 4"), "This is it, Mal!" before he went ahead and recorded his one and only attempt at a complete vocal take. the only attempt he needed to make. Concerning the effect used on Lennon's vocal on this song, Geoff Emerick stated: "It was not exactly an overwhelming vote of confidence at the time, but distortion was an effect he grew to love, and demand, on future Beatles recordings, not just on his voice, but on his guitar as well." "Even then, John wasn’t entirely happy with the result but, as usual, he was also impatient to get on with it. ‘Okay, that will do,’ he said abruptly after a brief run-through," exclaiming to assistant Mal Evans (as quietly heard on "Anthology 4"), "This is it, Mal!" before he went ahead and recorded his one and only attempt at a complete vocal take. the only attempt he needed to make. Concerning the effect used on Lennon's vocal on this song, Geoff Emerick stated: "It was not exactly an overwhelming vote of confidence at the time, but distortion was an effect he grew to love, and demand, on future Beatles recordings, not just on his voice, but on his guitar as well."

After these three overdubs were complete, George Martin, Geoff Emerick and 2nd engineer Ken Scott worked at creating a mono mix for the intended purpose of having acetate discs made. Even though the song had a long way to go, it was already complicated enough at this point for posing a detriment to getting a good mono mix done. The first three attempts were unsuccessful but the fourth mix, however, made it all the way through the end of the song and was deemed acceptable enough for now. After these three overdubs were complete, George Martin, Geoff Emerick and 2nd engineer Ken Scott worked at creating a mono mix for the intended purpose of having acetate discs made. Even though the song had a long way to go, it was already complicated enough at this point for posing a detriment to getting a good mono mix done. The first three attempts were unsuccessful but the fourth mix, however, made it all the way through the end of the song and was deemed acceptable enough for now.

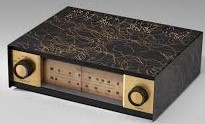

Geoff Emerick relates an idea of John’s that was experimented with at this mixing session and then eventually made it onto the finished song. "At the time, John and Paul were both heavily into avant-garde music, especially tracks that were based upon randomness…John was enthralled with the concept. As he listened to the playbacks of “I Am The Walrus,” he said, ‘You know, I think it would be great if I could put some random radio noise on the end of it – you know, just twiddling the dial, tuning into various stations to see what we get and how it fits with the music.’" Speculation has it that German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen's avant-garde piece "Hymnen," which was recorded sometime between 1966 and 1967, had inspired Lennon to want to include a radio scan in the finished mix of "I Am The Walrus." Karlheinz Stockhausen was admired by The Beatles enough to have been included in the top row of the faces on the front cover of the "Sgt Pepper" album. Geoff Emerick relates an idea of John’s that was experimented with at this mixing session and then eventually made it onto the finished song. "At the time, John and Paul were both heavily into avant-garde music, especially tracks that were based upon randomness…John was enthralled with the concept. As he listened to the playbacks of “I Am The Walrus,” he said, ‘You know, I think it would be great if I could put some random radio noise on the end of it – you know, just twiddling the dial, tuning into various stations to see what we get and how it fits with the music.’" Speculation has it that German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen's avant-garde piece "Hymnen," which was recorded sometime between 1966 and 1967, had inspired Lennon to want to include a radio scan in the finished mix of "I Am The Walrus." Karlheinz Stockhausen was admired by The Beatles enough to have been included in the top row of the faces on the front cover of the "Sgt Pepper" album.

“George Martin made a show of rolling his eyes heavenward, but I told John that it was perfectly doable. I arranged to have a radio tuner brought down from the maintenance office so we all could experiment with this. Given EMI Studio’s arcane procedures – a formal memo had to be written and approved – and the fact that the big, bulky rack-mounted tuner had to be rewired and then patched into the mixing console, it was quite an undertaking and not something we could put together quickly, which the ever-impatient John found highly frustrating. ‘Bloody EMI – can’t even get a radio organized!’ he snapped. But his face lit up when we finally got the sound going, and he had a lot of fun twiddling the dial as the multritrack tape of ‘Walrus’ played back. Because we knew that there was still a lot to be overdubbed onto the song, there wasn’t a track free to record John’s experimentations” “George Martin made a show of rolling his eyes heavenward, but I told John that it was perfectly doable. I arranged to have a radio tuner brought down from the maintenance office so we all could experiment with this. Given EMI Studio’s arcane procedures – a formal memo had to be written and approved – and the fact that the big, bulky rack-mounted tuner had to be rewired and then patched into the mixing console, it was quite an undertaking and not something we could put together quickly, which the ever-impatient John found highly frustrating. ‘Bloody EMI – can’t even get a radio organized!’ he snapped. But his face lit up when we finally got the sound going, and he had a lot of fun twiddling the dial as the multritrack tape of ‘Walrus’ played back. Because we knew that there was still a lot to be overdubbed onto the song, there wasn’t a track free to record John’s experimentations”

Brian Epstein’s assistant Alistair Taylor, who was present at this session, remembered the events: “We all were in Abbey Road and John suddenly disappeared and he came back and he said, ‘George (Martin), I am looking for a radio.’ We all looked at him and said, ‘What do you mean, you’re looking for a radio?’ George Martin said, ‘I’m sure there’s got to be a radio somewhere in the building.’ So, Lennon went off again and he found a radio on the floor above and he put it on short wave, because that was what he wanted. George Martin had to figure out how to get that radio from above down into the studio where they were recording.” Brian Epstein’s assistant Alistair Taylor, who was present at this session, remembered the events: “We all were in Abbey Road and John suddenly disappeared and he came back and he said, ‘George (Martin), I am looking for a radio.’ We all looked at him and said, ‘What do you mean, you’re looking for a radio?’ George Martin said, ‘I’m sure there’s got to be a radio somewhere in the building.’ So, Lennon went off again and he found a radio on the floor above and he put it on short wave, because that was what he wanted. George Martin had to figure out how to get that radio from above down into the studio where they were recording.”

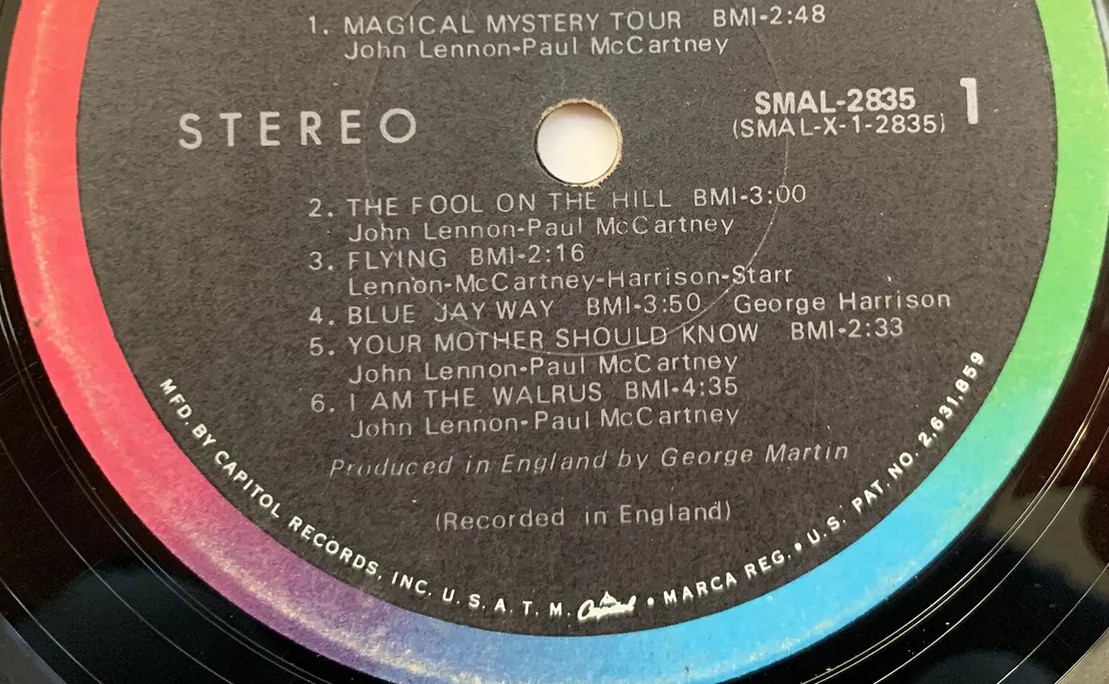

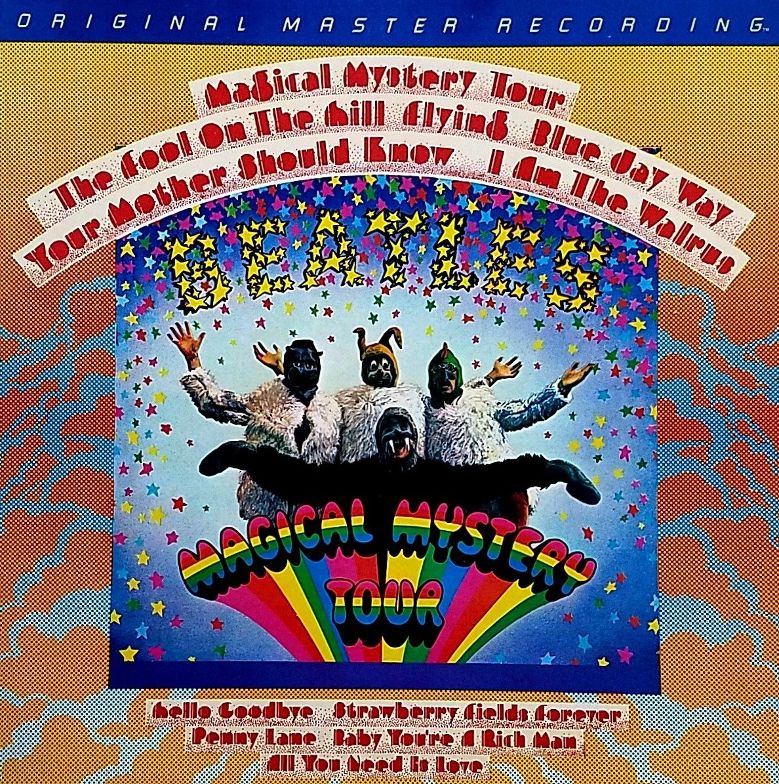

After this mix was complete, The Beatles began work on two new songs for the “Magical Mystery Tour” project, namely “The Fool On The Hill” and “Blue Jay Way.” By 3 am the following morning, this recording session was wrapped up for the night.

Since The Beatles needed to lip sync to “I Am The Walrus” for the “Magical Mystery Tour” TV film that was already in production, they needed a tape copy to listen to during the filming. The tape copy they used was created on September 16th, 1967, which was a duplicate copy of mono mix 4 as detailed above. This tape, made by George Martin, engineer Ken Scott and 2nd engineer Jeff Jarratt, was given directly to Garvik Losey, who was an assistant to the movie’s producer Denis O’Dell. The filming of the TV sequence for “I Am The Walrus” took place just days later, sometime between September 19th and 24th, 1967. Since The Beatles needed to lip sync to “I Am The Walrus” for the “Magical Mystery Tour” TV film that was already in production, they needed a tape copy to listen to during the filming. The tape copy they used was created on September 16th, 1967, which was a duplicate copy of mono mix 4 as detailed above. This tape, made by George Martin, engineer Ken Scott and 2nd engineer Jeff Jarratt, was given directly to Garvik Losey, who was an assistant to the movie’s producer Denis O’Dell. The filming of the TV sequence for “I Am The Walrus” took place just days later, sometime between September 19th and 24th, 1967.

By September 27th, 1967, George Martin had put together a very interesting score for an orchestra overdub for "I Am The Walrus." Back in April, George Martin's score for the song "Within You Without You" needed to accommodate various "sliding techniques" to specifically mimick Indian instrument performances. "What was difficult was writing a score for the cellists and violinists that the English players would be able to play like the Indians...bending the notes and with slurs between one note and the next." Now, four-and-a-half months later, George Martin had become more skilled in writing scores and instructing orchestra musicians in performing "all kinds of swoops." His score for "I Am The Walrus" had these classically trained musicians (some of the violinists also being used on "Within You Without You") "sliding" and "swooping" all over the place, something they were not accustoned to doing for other hired sessions. By September 27th, 1967, George Martin had put together a very interesting score for an orchestra overdub for "I Am The Walrus." Back in April, George Martin's score for the song "Within You Without You" needed to accommodate various "sliding techniques" to specifically mimick Indian instrument performances. "What was difficult was writing a score for the cellists and violinists that the English players would be able to play like the Indians...bending the notes and with slurs between one note and the next." Now, four-and-a-half months later, George Martin had become more skilled in writing scores and instructing orchestra musicians in performing "all kinds of swoops." His score for "I Am The Walrus" had these classically trained musicians (some of the violinists also being used on "Within You Without You") "sliding" and "swooping" all over the place, something they were not accustoned to doing for other hired sessions.

After first performing yet another tape reduction, sixteen session musicians were brought into EMI Studio One at 2:30 pm to record this score that featured eight violins, four cellos, a contra bass clarinet and three horns for this overdub session. "I discovered that the best way to work with an orchestra is to have the arranger over-write," Ken Scott related in his 2012 book "Abbey Road To Ziggy Stardust." "The reason is that it's always easier to get rid of material than to insert something in during a session. That is what George Martin used to do on his (orchestral) arrangements for Beatles songs, and that is what he did on 'Walrus.' The first hour of the session was John saying, 'I don't like that bit. Keep this bit. Can you change that a little?' George (Martin) made the changes and then we recorded it." One of the session horn players was even instructed to wildy ad lib in the final measures of the song in order to create a cacophony of sound for a "freak out" effect. It seems likely that this horn "freak out" conclusion was suggested by Lennon since one can hardly imagine George Martin desiring anything like that to be included on anything. After first performing yet another tape reduction, sixteen session musicians were brought into EMI Studio One at 2:30 pm to record this score that featured eight violins, four cellos, a contra bass clarinet and three horns for this overdub session. "I discovered that the best way to work with an orchestra is to have the arranger over-write," Ken Scott related in his 2012 book "Abbey Road To Ziggy Stardust." "The reason is that it's always easier to get rid of material than to insert something in during a session. That is what George Martin used to do on his (orchestral) arrangements for Beatles songs, and that is what he did on 'Walrus.' The first hour of the session was John saying, 'I don't like that bit. Keep this bit. Can you change that a little?' George (Martin) made the changes and then we recorded it." One of the session horn players was even instructed to wildy ad lib in the final measures of the song in order to create a cacophony of sound for a "freak out" effect. It seems likely that this horn "freak out" conclusion was suggested by Lennon since one can hardly imagine George Martin desiring anything like that to be included on anything.

Of the three full orchestral takes of the song, designated as takes 18 through 20 (the second, or "take 19," being featured in full on "Anthology 4"), the third attempt, "take 20," was deemed as best. In the liner notes of "Anthology 4," Kevin Howlett writes: "Playing along to the backing track from September 5th, the horns were recorded on track two of the four-track tape, strings were on three and the clarinet on four." Afterwards, four edit pieces was done as additions to "take 20," which was now designated as "take 24" after the edit pieces were completed. This afternoon session ended at 5:30 pm. Of the three full orchestral takes of the song, designated as takes 18 through 20 (the second, or "take 19," being featured in full on "Anthology 4"), the third attempt, "take 20," was deemed as best. In the liner notes of "Anthology 4," Kevin Howlett writes: "Playing along to the backing track from September 5th, the horns were recorded on track two of the four-track tape, strings were on three and the clarinet on four." Afterwards, four edit pieces was done as additions to "take 20," which was now designated as "take 24" after the edit pieces were completed. This afternoon session ended at 5:30 pm.

The Beatles were all present at the evening session on this day, which moved back over to EMI Studio Two and began somewhere around 7 pm. First on the agenda was creating yet another tape reduction in order to free up more space for the song, which now made the current recording “take 25.” The Beatles were all present at the evening session on this day, which moved back over to EMI Studio Two and began somewhere around 7 pm. First on the agenda was creating yet another tape reduction in order to free up more space for the song, which now made the current recording “take 25.”

And what was this overdub going to consist of? “The idea of using voices was a good one,” says George Martin. “We got in The Mike Sammes Singers, very commercial people and so alien to John that it wasn’t true. But in the score I simply orchestrated the laughs and noises, the whooooooah kind of thing. John was delighted with it.” Paul relates, “John worked with George Martin…and did some very exciting things with The Mike Sammes Singers, the likes of which they’ve never done before or since, like getting them to chant, ‘Everybody’s got one, everybody’s got one…,’ which they loved. It was a session to be remembered. Most of the time they got asked to do ‘Sing Something Simple’ and all the old songs, but John got them doing all sorts of swoops and phonetic noises. It was a fascinating session. That was John’s baby, great one, a really good one." And what was this overdub going to consist of? “The idea of using voices was a good one,” says George Martin. “We got in The Mike Sammes Singers, very commercial people and so alien to John that it wasn’t true. But in the score I simply orchestrated the laughs and noises, the whooooooah kind of thing. John was delighted with it.” Paul relates, “John worked with George Martin…and did some very exciting things with The Mike Sammes Singers, the likes of which they’ve never done before or since, like getting them to chant, ‘Everybody’s got one, everybody’s got one…,’ which they loved. It was a session to be remembered. Most of the time they got asked to do ‘Sing Something Simple’ and all the old songs, but John got them doing all sorts of swoops and phonetic noises. It was a fascinating session. That was John’s baby, great one, a really good one."

Ray Thomas of The Moody Blues, in a 2015 interview with Stephen Schnee, relates how fellow bandmate Mike Pinder and himself also took part in this vocal overdub. "We were very friendly at the time with The Beatles," Ray Thomas explains. "Mike (Pinder) and I went into Abbey Road...and did some backing vocals on 'Walrus.'” Lennon relates, “I had this whole choir saying, ‘Everybody’s got one, everybody’s got one,’ but when you get thirty people, male and female, on top of thirty cellos and on top of The Beatles’ rock’n’roll rhythm section, you can’t hear what they’re saying.” Although engineer Geoff Emerick was not present on the day of this overdub, he remembers his pleasant surprise on hearing the tapes of this overdub on his return, describing the vocalists as also singing, “Oompah, oompah, stick it up your jumper” and of course, “Ho-ho-ho, hee-hee-hee, ha-ha-ha.” Ray Thomas of The Moody Blues, in a 2015 interview with Stephen Schnee, relates how fellow bandmate Mike Pinder and himself also took part in this vocal overdub. "We were very friendly at the time with The Beatles," Ray Thomas explains. "Mike (Pinder) and I went into Abbey Road...and did some backing vocals on 'Walrus.'” Lennon relates, “I had this whole choir saying, ‘Everybody’s got one, everybody’s got one,’ but when you get thirty people, male and female, on top of thirty cellos and on top of The Beatles’ rock’n’roll rhythm section, you can’t hear what they’re saying.” Although engineer Geoff Emerick was not present on the day of this overdub, he remembers his pleasant surprise on hearing the tapes of this overdub on his return, describing the vocalists as also singing, “Oompah, oompah, stick it up your jumper” and of course, “Ho-ho-ho, hee-hee-hee, ha-ha-ha.”

These sixteen vocalists (eight men and eight women) performed all their outrageous overdubs onto track one of the four-track tape of "take 25" in the next seven hours or so, thus ending their recording stint for the day by approximately 2 am the next morning. “The next day we did a Kathy Kirby session at Pye Studios,” Mike Sammes recounts from consulting his diaries, “then ‘The Benny Hill Show’ for ATV and we had some men doing recordings for ‘The Gang Show’ at Chappells!” These sixteen vocalists (eight men and eight women) performed all their outrageous overdubs onto track one of the four-track tape of "take 25" in the next seven hours or so, thus ending their recording stint for the day by approximately 2 am the next morning. “The next day we did a Kathy Kirby session at Pye Studios,” Mike Sammes recounts from consulting his diaries, “then ‘The Benny Hill Show’ for ATV and we had some men doing recordings for ‘The Gang Show’ at Chappells!”

By 3:30 am, after Paul recorded some additional vocals for the song “The Fool On The Hill,” creating the need for another mono mix of that song to be made, the session was finally over. With all this work being done on “I Am The Walrus” at this point, everyone may have thought that the song was complete. This was surprisingly not the case! By 3:30 am, after Paul recorded some additional vocals for the song “The Fool On The Hill,” creating the need for another mono mix of that song to be made, the session was finally over. With all this work being done on “I Am The Walrus” at this point, everyone may have thought that the song was complete. This was surprisingly not the case!

The next day (or should I say later that day), September 28th, 1967, intricate work was undertaken to create a usable mono mix of the song. George Martin and engineers Ken Scott and Richard Lush entered the control room of EMI Studio Two at 4 pm for work on some of the “Magical Mystery Tour” songs. After creating tape copies of the film’s title song and “Flying” for use in the actual film, they gave attention to “I Am The Walrus” by syncing up two tape machines to combine the previous day's finished recording (“take 25,” containing all recorded elements so far bounced down to one track) onto track two of the four-track tape that contained the rhythm track, Paul’s bass and John’s vocal (“take 17”). They had to have worked very hard to sync up these two tapes to get them to mesh well together, the results showing a slight variation in tape speeds noticeable on the finished product (especially where the drums come in for the first time). At 5:30 pm, this session was complete. The next day (or should I say later that day), September 28th, 1967, intricate work was undertaken to create a usable mono mix of the song. George Martin and engineers Ken Scott and Richard Lush entered the control room of EMI Studio Two at 4 pm for work on some of the “Magical Mystery Tour” songs. After creating tape copies of the film’s title song and “Flying” for use in the actual film, they gave attention to “I Am The Walrus” by syncing up two tape machines to combine the previous day's finished recording (“take 25,” containing all recorded elements so far bounced down to one track) onto track two of the four-track tape that contained the rhythm track, Paul’s bass and John’s vocal (“take 17”). They had to have worked very hard to sync up these two tapes to get them to mesh well together, the results showing a slight variation in tape speeds noticeable on the finished product (especially where the drums come in for the first time). At 5:30 pm, this session was complete.

However, the next session of the day began around 7 pm in the same studio, this time with The Beatles present. This session began with an actual attempt by the same engineering team at creating the coveted mono mix of “I Am The Walrus.” They took the newly created “take 17” and made four tries at making a mono mix (incorrectly numbered 2 through 5), their first attempt (“remix 2”) being deemed the best at this point. Then they performed some editing of “remix 2” to get it to what they thought was a finished state. This being completed at around 9 pm, the rest of the session was devoted to the song “Flying,” this session not winding up until 3 am the following morning. However, the next session of the day began around 7 pm in the same studio, this time with The Beatles present. This session began with an actual attempt by the same engineering team at creating the coveted mono mix of “I Am The Walrus.” They took the newly created “take 17” and made four tries at making a mono mix (incorrectly numbered 2 through 5), their first attempt (“remix 2”) being deemed the best at this point. Then they performed some editing of “remix 2” to get it to what they thought was a finished state. This being completed at around 9 pm, the rest of the session was devoted to the song “Flying,” this session not winding up until 3 am the following morning.

Later that evening, September 29th, 1967, The Beatles convened again in EMI Studio Two around 7 pm to once again try to perfect the mono mix of “I Am The Walrus.” George Martin, Ken Scott and 2nd engineer Graham Kirkby rolled the tape a total of 17 times to get it right (numbered takes 6 through 22), although only two of these attempts made it all the way through to the end of the song, "take 10" and "take 22." What especially made it problematic was their experimenting with changing different elements of the song along the way. “Take 10” shows the following changes: Two of the six beats on the introduction were cut off, a cymbal crash after the first “goo goo gajoob” was mixed out, Ringo’s drums are totally mixed out just after the first two times John sings “I’m crying,” and a full measure was edited out just before the lyrics “yellow matter custard.” Later that evening, September 29th, 1967, The Beatles convened again in EMI Studio Two around 7 pm to once again try to perfect the mono mix of “I Am The Walrus.” George Martin, Ken Scott and 2nd engineer Graham Kirkby rolled the tape a total of 17 times to get it right (numbered takes 6 through 22), although only two of these attempts made it all the way through to the end of the song, "take 10" and "take 22." What especially made it problematic was their experimenting with changing different elements of the song along the way. “Take 10” shows the following changes: Two of the six beats on the introduction were cut off, a cymbal crash after the first “goo goo gajoob” was mixed out, Ringo’s drums are totally mixed out just after the first two times John sings “I’m crying,” and a full measure was edited out just before the lyrics “yellow matter custard.”

John’s brainchild of having the sound of “twiddling the dial” of a radio was incorporated into the second complete mono mix made on this day, namely “take 22.” However, since there wasn’t an available track on the tape left to record the radio, they needed to accommodate John’s idea somehow. Geoff Emerick explains: "(John) ended up repeating the exercise, with Ringo twiddling the dial, when the mono mix was done…That’s the reason why ‘I Am The Walrus’ can never be remixed: the radio wasn’t recorded on the multitrack. Instead, it was flown into the two-track, live, as the mix was occurring." However, with AI techology developed much later, the song could indeed be remixed, as we'll see below. John’s brainchild of having the sound of “twiddling the dial” of a radio was incorporated into the second complete mono mix made on this day, namely “take 22.” However, since there wasn’t an available track on the tape left to record the radio, they needed to accommodate John’s idea somehow. Geoff Emerick explains: "(John) ended up repeating the exercise, with Ringo twiddling the dial, when the mono mix was done…That’s the reason why ‘I Am The Walrus’ can never be remixed: the radio wasn’t recorded on the multitrack. Instead, it was flown into the two-track, live, as the mix was occurring." However, with AI techology developed much later, the song could indeed be remixed, as we'll see below.

And what happened to be on the radio that evening? Mark Lewisohn’s book “The Beatles Recording Sessions” relates: “The tuning dial eventually came to rest on the BBC Third Programme…while a 190-minute production of Shakespeare’s ‘The Tragedy Of King Lear’ was being broadcast. Parts of Act IV Scene VI can be heard on the record, commencing with the lines, spoken by Gloucester and Edgar respectively, ‘Now, good sir, what are you?’ and ‘A most poor man, made tame by fortune’s blows.’ The Shakespeare broadcast is particularly evident at the end of the song, from Oswald’s ‘…take my purse’ through to Edgar’s ‘Sit you down, father; rest you.’ Whether the actors concerned – Mark Dignam (Gloucester), Philip Guard (Edgar) and John Bryning (Oswald) – have discovered their appearance on a Beatles record is not known.” And what happened to be on the radio that evening? Mark Lewisohn’s book “The Beatles Recording Sessions” relates: “The tuning dial eventually came to rest on the BBC Third Programme…while a 190-minute production of Shakespeare’s ‘The Tragedy Of King Lear’ was being broadcast. Parts of Act IV Scene VI can be heard on the record, commencing with the lines, spoken by Gloucester and Edgar respectively, ‘Now, good sir, what are you?’ and ‘A most poor man, made tame by fortune’s blows.’ The Shakespeare broadcast is particularly evident at the end of the song, from Oswald’s ‘…take my purse’ through to Edgar’s ‘Sit you down, father; rest you.’ Whether the actors concerned – Mark Dignam (Gloucester), Philip Guard (Edgar) and John Bryning (Oswald) – have discovered their appearance on a Beatles record is not known.”

“We did this on the remix,” Lennon explained at the time. “When we were remixing, we had all of the voices, which we just brought in as we were doing it, sort of ad-lib. So it’s not editing at all, it was just all going on. We did the loops like that so they’re all going on at the time, and we’d just bring them in now and again…When we made it, we had a live radio coming through. It was just whatever came through on the radio was coming through. If I said, ‘I want the radio on it,’ George (Martin) would make it so I could mix and the radio would be coming through the machine.” When John was asked who was working the controls, he replied: “About ten of us, whoever. It’s just all sorts of people. There’s me, Paul, or anybody who’s around.” “We did this on the remix,” Lennon explained at the time. “When we were remixing, we had all of the voices, which we just brought in as we were doing it, sort of ad-lib. So it’s not editing at all, it was just all going on. We did the loops like that so they’re all going on at the time, and we’d just bring them in now and again…When we made it, we had a live radio coming through. It was just whatever came through on the radio was coming through. If I said, ‘I want the radio on it,’ George (Martin) would make it so I could mix and the radio would be coming through the machine.” When John was asked who was working the controls, he replied: “About ten of us, whoever. It’s just all sorts of people. There’s me, Paul, or anybody who’s around.”

“John liked playing around,” explained George Martin, “but he wasn’t a good technician. He couldn’t handle equipment all that well, but he was always trying to get new effects. John was moving the faders around during ‘Walrus,’ because someone had to do something at random; he wasn’t running the show.” “John liked playing around,” explained George Martin, “but he wasn’t a good technician. He couldn’t handle equipment all that well, but he was always trying to get new effects. John was moving the faders around during ‘Walrus,’ because someone had to do something at random; he wasn’t running the show.”

“I never knew it was ‘King Lear’ until, years later, somebody told me,” John said in 1974, “because I could hardly make out what he was saying. It was interesting to mix the whole thing with a live radio coming through it. So that’s the secret of that one.”

From the two complete mixes made on this day, it was decided to edit together the first half of “take 10” with the second half of “take 22,” the edit appearing just before the lyrics “Sitting in an English garden.” The combination of these two takes was now being called “take 23,” this being the mono mix released in Britain on the single and “Magical Mystery Tour” EP. It appears that Capitol Records in the US was inadvertently sent the unedited “take 22” instead, the differences including the full measure of music still being in place just before the lyric “yellow matter custard” is heard. From the two complete mixes made on this day, it was decided to edit together the first half of “take 10” with the second half of “take 22,” the edit appearing just before the lyrics “Sitting in an English garden.” The combination of these two takes was now being called “take 23,” this being the mono mix released in Britain on the single and “Magical Mystery Tour” EP. It appears that Capitol Records in the US was inadvertently sent the unedited “take 22” instead, the differences including the full measure of music still being in place just before the lyric “yellow matter custard” is heard.