Recording History

Session One: Two days after that issue of the “Daily Mail” came out, The Beatles entered EMI Studio Two around 7:30 pm to begin the song that was titled, for this day only, “In The Life Of…”

Engineer Geoff Emerick, in his book “Here, There And Everywhere,” explains in intricate detail the humble beginnings of this monumental song: “One mid-January evening, the four Beatles rolled up, a little bit stoned, as had become usual, but with a tinge of excitement. They had a new song they’d been working on…and they were anxious to play it for George Martin and me. They had gotten in the habit of meeting at Paul’s house in nearby St. John’s Wood before sessions, where they’d have a cup of tea, perhaps a puff of a joint, and John and Paul would finish up any songs that were still in progress. Once a song was complete, the four of them would start routining it right there and then, working out parts, learning the chords and time changes, all before they got to the studio. They would then get in their respective cars and be driven over to Abbey Road – although it was walking distance, they couldn’t take a stroll because of all the fans – which explained why they always showed up together despite living considerable distances from one another.”

Engineer Geoff Emerick, in his book “Here, There And Everywhere,” explains in intricate detail the humble beginnings of this monumental song: “One mid-January evening, the four Beatles rolled up, a little bit stoned, as had become usual, but with a tinge of excitement. They had a new song they’d been working on…and they were anxious to play it for George Martin and me. They had gotten in the habit of meeting at Paul’s house in nearby St. John’s Wood before sessions, where they’d have a cup of tea, perhaps a puff of a joint, and John and Paul would finish up any songs that were still in progress. Once a song was complete, the four of them would start routining it right there and then, working out parts, learning the chords and time changes, all before they got to the studio. They would then get in their respective cars and be driven over to Abbey Road – although it was walking distance, they couldn’t take a stroll because of all the fans – which explained why they always showed up together despite living considerable distances from one another.”

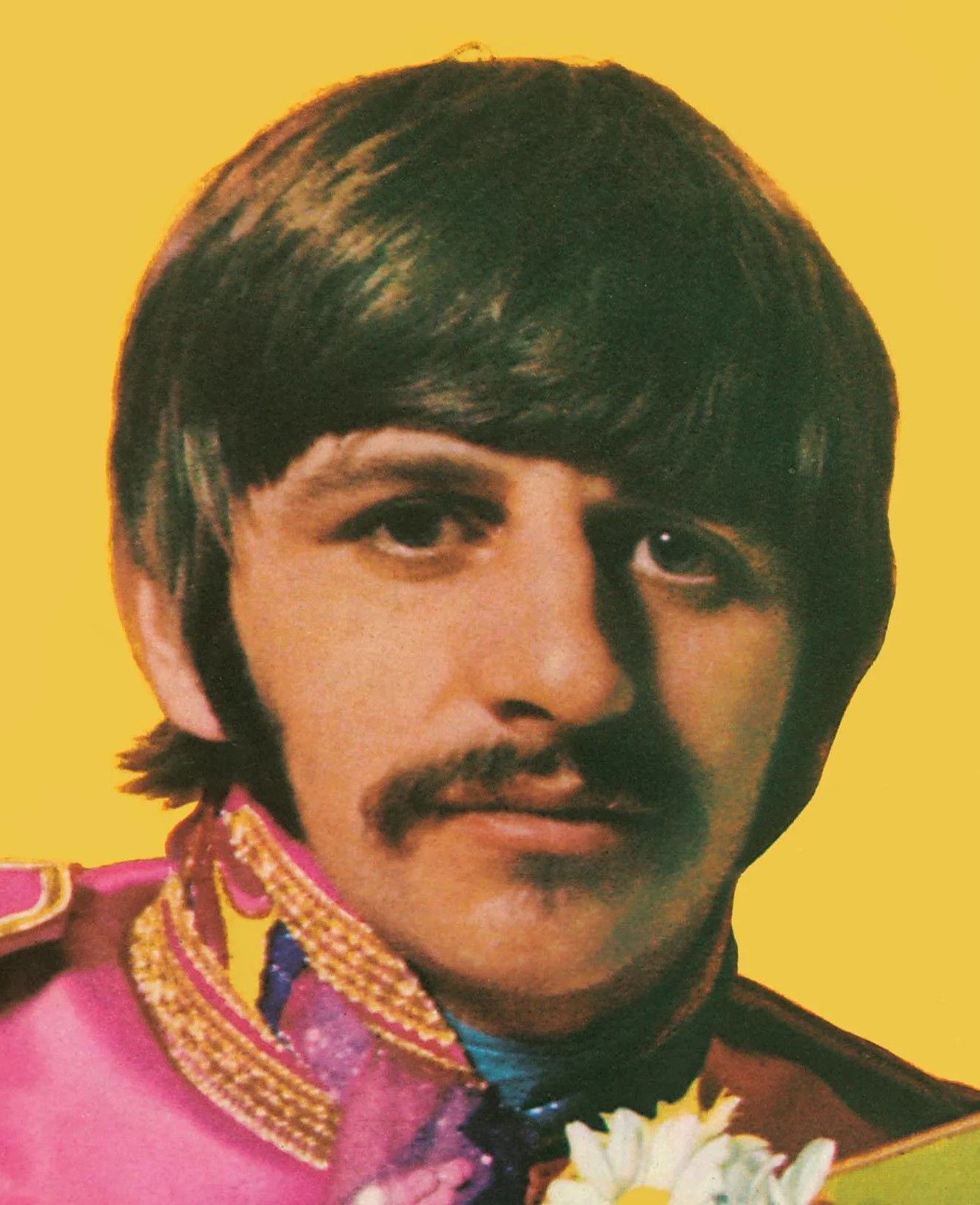

“The song…was in a similar vein to “Strawberry Fields Forever” – light and dreamy – but it was somehow even more compelling. I was in awe; I distinctly remember thinking, ‘Christ, John’s topped himself!’ As Lennon sang softly, strumming his acoustic guitar, Paul accompanied him on piano. A lot of thought must have gone into the piano part, because it was providing a perfect counterpoint to John’s vocal and guitar playing. Ringo joined on bongos, while George Harrison, who seemed to have been given nothing specific to do, idly shook a pair of maracas.”

“The song…was in a similar vein to “Strawberry Fields Forever” – light and dreamy – but it was somehow even more compelling. I was in awe; I distinctly remember thinking, ‘Christ, John’s topped himself!’ As Lennon sang softly, strumming his acoustic guitar, Paul accompanied him on piano. A lot of thought must have gone into the piano part, because it was providing a perfect counterpoint to John’s vocal and guitar playing. Ringo joined on bongos, while George Harrison, who seemed to have been given nothing specific to do, idly shook a pair of maracas.”

"The song, as played during that first run-through, consisted simply of a short introduction, three verses, and two perfunctory choruses. The only lyric in the chorus was a rather daring ‘I’d love to turn you on’ – six provocative words that would result in the song being banned by the BBC. Obviously more was needed to flesh it out…There was a great deal of discussion about what to do, but no real resolution. Paul thought he might have something that would fit, but for the moment everyone was keen to start recording, so it was decided simply to leave twenty-four empty bars in the middle as a kind of placeholder. This in itself was unique in Beatles recording: the song was clearly unfinished, but it was so good nonetheless that it was decided to plow ahead and get it down on tape and then finish it later. In essence, the composition was going to be structured during the recording stage. Without any conscious forethought, we were in the process of creating not just a song, but a musical work of art."

"The song, as played during that first run-through, consisted simply of a short introduction, three verses, and two perfunctory choruses. The only lyric in the chorus was a rather daring ‘I’d love to turn you on’ – six provocative words that would result in the song being banned by the BBC. Obviously more was needed to flesh it out…There was a great deal of discussion about what to do, but no real resolution. Paul thought he might have something that would fit, but for the moment everyone was keen to start recording, so it was decided simply to leave twenty-four empty bars in the middle as a kind of placeholder. This in itself was unique in Beatles recording: the song was clearly unfinished, but it was so good nonetheless that it was decided to plow ahead and get it down on tape and then finish it later. In essence, the composition was going to be structured during the recording stage. Without any conscious forethought, we were in the process of creating not just a song, but a musical work of art."

In the book "With A Little Help From My Friends," George Martin relates how, after John premiered his "I read the news today..." verses during the above mentioned run-through, the singer announced, "I don't know where to go from here," which prompted Paul to offer up the suggestion, "Well, I've got this other song I've been working on," referring to his "Woke up, fell out of bed..." composition.

Concerning the process used for recording the song at this point, Mark Lewisohn’s book “The Beatles Recording Sessions” notes: “Take one of ‘A Day In The Life’ used just two of the four available tracks: a basic rhythm (bongos, maracas, piano and guitar) on track one and a heavily echoed Lennon vocal on track four.”

Concerning the process used for recording the song at this point, Mark Lewisohn’s book “The Beatles Recording Sessions” notes: “Take one of ‘A Day In The Life’ used just two of the four available tracks: a basic rhythm (bongos, maracas, piano and guitar) on track one and a heavily echoed Lennon vocal on track four.”

With John on acoustic guitar and Paul on piano, a change needed to be made regarding the other percussion instruments. “After the first run-through with Harrison on maracas,” remembers Geoff Emerick, "George Martin turned to me in the control room and said, ‘He’s not very steady, is he? I think I’ll have him switch with Ringo,’ and I concurred. Ringo was a much better timekeeper, and George Harrison’s concentration used to wander too much to keep a steady tempo for three or four minutes straight. I mixed the little bit of noodling Harrison ended up doing on the bongos so far in the background that it was nearly inaudible." It's important to note here that when both Mark Lewisohn and Geoff Emerick mention the use of "bongos" during the recording of this song, what is apparently meant is conga drums, these being present in EMI Studio Two during these sessions, as photographic evidence bears out.

With John on acoustic guitar and Paul on piano, a change needed to be made regarding the other percussion instruments. “After the first run-through with Harrison on maracas,” remembers Geoff Emerick, "George Martin turned to me in the control room and said, ‘He’s not very steady, is he? I think I’ll have him switch with Ringo,’ and I concurred. Ringo was a much better timekeeper, and George Harrison’s concentration used to wander too much to keep a steady tempo for three or four minutes straight. I mixed the little bit of noodling Harrison ended up doing on the bongos so far in the background that it was nearly inaudible." It's important to note here that when both Mark Lewisohn and Geoff Emerick mention the use of "bongos" during the recording of this song, what is apparently meant is conga drums, these being present in EMI Studio Two during these sessions, as photographic evidence bears out.

Regarding the empty twenty-four bars separating the distinct sections of the song, George Martin, in his book “All You Need Is Ears,” recalls: “When we recorded the original track it was just Paul banging away on the same piano note, bar after bar, for twenty-four bars. We agreed that it was a question of ‘This space to be filled later.’ In order to keep time, we got Mal Evans to count each bar, and on the record you can still hear his voice as he stood by the piano counting: ‘One – two – three – four…’ For a joke, Mal set an alarm clock to go off at the end of twenty-four bars, and you can hear that too. We left it in because we couldn’t get it off!”

Regarding the empty twenty-four bars separating the distinct sections of the song, George Martin, in his book “All You Need Is Ears,” recalls: “When we recorded the original track it was just Paul banging away on the same piano note, bar after bar, for twenty-four bars. We agreed that it was a question of ‘This space to be filled later.’ In order to keep time, we got Mal Evans to count each bar, and on the record you can still hear his voice as he stood by the piano counting: ‘One – two – three – four…’ For a joke, Mal set an alarm clock to go off at the end of twenty-four bars, and you can hear that too. We left it in because we couldn’t get it off!”

Geoff Emerick explains further: “Mal Evans was dispatched to stand by the piano and count off the twenty-four bars in the middle so that each Beatle could focus on his playing and not have to think about it. Though Mal’s voice was fed into the headphones, it was not meant to be recorded, but he got more and more excited as the count progressed, raising his voice louder and louder. As a result, it began feeding through on to the other mics, so some of it even survived onto the final mix. There also happened to be a windup alarm clock set on top of the piano – Lennon had brought it in as a gag one day, saying that it would come in handy for waking up Ringo when he was needed for an overdub. In a fit of silliness, Mal (Evans) decided to set it off at the start of the 24th bar; that, too, made it onto the finished recording…for no reason other than that I couldn’t get rid of it." And, as the book "The Beatles Recording Sessions" explains, "To enter into the true spirit of the Beatles' recordings 1967-style, this labored counting was plastered with tape echo, increasing with the numbers until by '24' it sounded like he was in a cave.”

Geoff Emerick explains further: “Mal Evans was dispatched to stand by the piano and count off the twenty-four bars in the middle so that each Beatle could focus on his playing and not have to think about it. Though Mal’s voice was fed into the headphones, it was not meant to be recorded, but he got more and more excited as the count progressed, raising his voice louder and louder. As a result, it began feeding through on to the other mics, so some of it even survived onto the final mix. There also happened to be a windup alarm clock set on top of the piano – Lennon had brought it in as a gag one day, saying that it would come in handy for waking up Ringo when he was needed for an overdub. In a fit of silliness, Mal (Evans) decided to set it off at the start of the 24th bar; that, too, made it onto the finished recording…for no reason other than that I couldn’t get rid of it." And, as the book "The Beatles Recording Sessions" explains, "To enter into the true spirit of the Beatles' recordings 1967-style, this labored counting was plastered with tape echo, increasing with the numbers until by '24' it sounded like he was in a cave.”

As the tape began rolling for "take one," as Geoff Emerick announces "'In The Life Of...' 'take one'" (as the song was then called) and the players fiddled about on their instruments, we then hear John instructing the engineers by saying: “Cut the mike on the piano quite low, just, just keep it in my maracas, you know. You know those old pianos!” “Normally it was Paul who did the count-in at the start of a song,” Geoff Emerick states, “even if it were a Lennon or Harrison composition, simply because he had the best sense of what would be the optimum tempo. Occasionally, however, John would count in his own songs. Whenever he did, he would substitute nonsense words: the standard ‘one, two, three, four’ just wasn’t good enough for him. On this particular cold January evening – close enough to the holidays that the Christmas trees in most homes were still up – he opted to use the phrase ‘sugarplum fairy, sugarplum fairy’ instead, which gave us all a chuckle up in the control room.” Some sources say this phrase referred to drug suppliers of that time, but this has not been verified with any certainty.

As the tape began rolling for "take one," as Geoff Emerick announces "'In The Life Of...' 'take one'" (as the song was then called) and the players fiddled about on their instruments, we then hear John instructing the engineers by saying: “Cut the mike on the piano quite low, just, just keep it in my maracas, you know. You know those old pianos!” “Normally it was Paul who did the count-in at the start of a song,” Geoff Emerick states, “even if it were a Lennon or Harrison composition, simply because he had the best sense of what would be the optimum tempo. Occasionally, however, John would count in his own songs. Whenever he did, he would substitute nonsense words: the standard ‘one, two, three, four’ just wasn’t good enough for him. On this particular cold January evening – close enough to the holidays that the Christmas trees in most homes were still up – he opted to use the phrase ‘sugarplum fairy, sugarplum fairy’ instead, which gave us all a chuckle up in the control room.” Some sources say this phrase referred to drug suppliers of that time, but this has not been verified with any certainty.

Paul’s middle section to the song (“woke up, fell out of bed…”) was already in place from the first take on this day. However, as Mark Lewisohn points out, “there was no Paul McCartney vocal yet, merely instruments at the point where his contribution would later be placed, but then John’s vocal returned, leading into another Mal Evans one-to twenty-four count and then a single piano – building, building, building, building, stop. Breathtaking stuff indeed.”

George Martin explains in the film “The Making Of Sgt. Pepper” about the initial vocal John put down on 'take one': “John was singing while he was playing his acoustic guitar. Even in this early take, he has a voice which sends shivers down the spine." "Once he started singing, we were all stunned into silence," Geoff Emerick continues, "the raw emotion in his voice made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up." 'Take two,' which also saw the song to completion, had an even more spine-chilling vocal from John, him counting it down simple as "one, two, three four" this time. One noticeable difference this time was that Mal Evans mistakenly began counting off his 24 measures one measur too early the first time around, which possibly may have been the only reason this 'take' didn't make the cut. Both "take one" and "take two" can be heard unaltered in various editions of the "Sgt. Pepper" 50th Anniversary releases.

George Martin explains in the film “The Making Of Sgt. Pepper” about the initial vocal John put down on 'take one': “John was singing while he was playing his acoustic guitar. Even in this early take, he has a voice which sends shivers down the spine." "Once he started singing, we were all stunned into silence," Geoff Emerick continues, "the raw emotion in his voice made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up." 'Take two,' which also saw the song to completion, had an even more spine-chilling vocal from John, him counting it down simple as "one, two, three four" this time. One noticeable difference this time was that Mal Evans mistakenly began counting off his 24 measures one measur too early the first time around, which possibly may have been the only reason this 'take' didn't make the cut. Both "take one" and "take two" can be heard unaltered in various editions of the "Sgt. Pepper" 50th Anniversary releases.

Geoff Emerick continues: "Once the sparse backing track was deemed satisfactory ("take four"), Lennon did take after take of the lead vocal, each heavily laden with tape echo, each more amazing than the one before. His vocal performance that night was an absolute tour de force, and it was all George Martin, Phil (McDonald) and I could talk about long after the sessions ended."

Geoff Emerick continues: "Once the sparse backing track was deemed satisfactory ("take four"), Lennon did take after take of the lead vocal, each heavily laden with tape echo, each more amazing than the one before. His vocal performance that night was an absolute tour de force, and it was all George Martin, Phil (McDonald) and I could talk about long after the sessions ended."

Regarding these vocal overdubs, Mark Lewisohn notes: “With 'take four' John began a series of vocal overdubs onto the two vacant tracks, so that by the evening’s end the four-track tape included three separate Lennon vocals, all with heavy echo.” Engineer Geoff Emerick interjects: “There was so much echo on ‘A Day In The Life.’ We’d send a feed from John’s vocal mike into a mono tape machine and then tape the output – because they had separate record and replay heads – and then feed that back in again. Then we’d turn up the record level until it started to feed back on itself and give a twittery sort of vocal sound. John was hearing that echo in his cans (headphones) as he was singing. It wasn’t put on after. He used his own echo as a rhythmic feel for many of the songs he sang, phrasing his voice around the echo in his cans.”

Regarding these vocal overdubs, Mark Lewisohn notes: “With 'take four' John began a series of vocal overdubs onto the two vacant tracks, so that by the evening’s end the four-track tape included three separate Lennon vocals, all with heavy echo.” Engineer Geoff Emerick interjects: “There was so much echo on ‘A Day In The Life.’ We’d send a feed from John’s vocal mike into a mono tape machine and then tape the output – because they had separate record and replay heads – and then feed that back in again. Then we’d turn up the record level until it started to feed back on itself and give a twittery sort of vocal sound. John was hearing that echo in his cans (headphones) as he was singing. It wasn’t put on after. He used his own echo as a rhythmic feel for many of the songs he sang, phrasing his voice around the echo in his cans.”

The session ended at 2:30 am the following morning and, although all four tracks of the master tape were filled, it was obvious that much more work would be required to get it to a finished state. What wasn’t obvious, however, was what actually would be required to get it to that state.

Session Two: The Beatles filed into EMI Studio Two once again later that evening, January 20th, 1967, for more work on the song. “The next night’s session began with an intensive review of what had been laid down on tape,” Geoff Emerick states. “Our job was to decide which of John’s lead vocals was the keeper. We didn’t have to necessarily use the entire performance, though. Because we had the luxury of working in four-track, I could copy over (“bounce”) the best lines from each take into one track – a process known as ‘comping.’ This is a recording technique that is still very much in use today…All we were really listening for when we were comping John’s vocal was phrasing and inflection; he never had trouble hitting the notes spot on. Lennon sat behind the mixing console with George Martin and me, picking out the bits he liked. Paul was up in the control room, too, expressing his opinions, but George Harrison and Ringo stayed down in the studio; they just weren’t involved to that extent.”

Session Two: The Beatles filed into EMI Studio Two once again later that evening, January 20th, 1967, for more work on the song. “The next night’s session began with an intensive review of what had been laid down on tape,” Geoff Emerick states. “Our job was to decide which of John’s lead vocals was the keeper. We didn’t have to necessarily use the entire performance, though. Because we had the luxury of working in four-track, I could copy over (“bounce”) the best lines from each take into one track – a process known as ‘comping.’ This is a recording technique that is still very much in use today…All we were really listening for when we were comping John’s vocal was phrasing and inflection; he never had trouble hitting the notes spot on. Lennon sat behind the mixing console with George Martin and me, picking out the bits he liked. Paul was up in the control room, too, expressing his opinions, but George Harrison and Ringo stayed down in the studio; they just weren’t involved to that extent.”

Three attempts at tape reductions were made, numbered 5 through 7, although “take six” was the one decided to be the best. Being brought over to a new four-track tape, this opened up tracks for more overdubs, two of which were Paul’s bass guitar and Ringo’s drums, both recorded on this day. A relatively standard recording technique was used on the drums at this stage, while Ringo put in an inventive performance with emphasis on extensive drum fills focused around the snare drum. Paul also put in an interesting bass guitar overdub, a unique feature being a mimic of John’s warbly vocal performance for the words “turn…you…on” as the bass proceeds into the 24 bar count-downs of the song. And then, a very psychedelic “freak-out” bass part at the end which he undoubtedly figured would be faded out. Also overdubbed on this day was a bit more piano from Paul on the introduction, just before John began singing, to add a little swell of volume before the vocals came in.

Three attempts at tape reductions were made, numbered 5 through 7, although “take six” was the one decided to be the best. Being brought over to a new four-track tape, this opened up tracks for more overdubs, two of which were Paul’s bass guitar and Ringo’s drums, both recorded on this day. A relatively standard recording technique was used on the drums at this stage, while Ringo put in an inventive performance with emphasis on extensive drum fills focused around the snare drum. Paul also put in an interesting bass guitar overdub, a unique feature being a mimic of John’s warbly vocal performance for the words “turn…you…on” as the bass proceeds into the 24 bar count-downs of the song. And then, a very psychedelic “freak-out” bass part at the end which he undoubtedly figured would be faded out. Also overdubbed on this day was a bit more piano from Paul on the introduction, just before John began singing, to add a little swell of volume before the vocals came in.

Interestingly, George Harrison took to adding an electric rhythm guitar part to the song as an overdub on this day which, when listening to the existing tape, is especially discernible as the first verse concludes, but apparently didn't make it to the released version. John also overdubbed himself double-tracking his vocals in two strategic places: the phrases “I’d love to turn you on” as well as the quick falsetto words that precede these passages. One other overdub that occurred on this day concerned the middle section of the song. Paul took to recording a guide vocal here for the first time, although it wasn’t meant to be the finished version; just a guide to show how it would work with the song. Geoff Emerick states: “In what could only be described as pure serendipity, it happened to begin with the lyric ‘woke up, fell out of bed…’ which, incredibly, perfectly fit the alarm clock ringing. If ever there was an omen that this was to be a very special song in the Beatles canon, this was it.”

Interestingly, George Harrison took to adding an electric rhythm guitar part to the song as an overdub on this day which, when listening to the existing tape, is especially discernible as the first verse concludes, but apparently didn't make it to the released version. John also overdubbed himself double-tracking his vocals in two strategic places: the phrases “I’d love to turn you on” as well as the quick falsetto words that precede these passages. One other overdub that occurred on this day concerned the middle section of the song. Paul took to recording a guide vocal here for the first time, although it wasn’t meant to be the finished version; just a guide to show how it would work with the song. Geoff Emerick states: “In what could only be described as pure serendipity, it happened to begin with the lyric ‘woke up, fell out of bed…’ which, incredibly, perfectly fit the alarm clock ringing. If ever there was an omen that this was to be a very special song in the Beatles canon, this was it.”

This vocal was perfected two weeks later, Paul’s new vocal wiping out this guide vocal in the process. This preliminary version, however, was still preserved on tape and has been made available on the 1996 release “Anthology 2,” even with the expletive “oh, sh*t” at the end after he mistakenly sang “everybody spoke and I went into a dream.”

This vocal was perfected two weeks later, Paul’s new vocal wiping out this guide vocal in the process. This preliminary version, however, was still preserved on tape and has been made available on the 1996 release “Anthology 2,” even with the expletive “oh, sh*t” at the end after he mistakenly sang “everybody spoke and I went into a dream.”

As for this second session for the song, it ended at 12:10 am the following morning. The Beatles then took a ten day break from recording, during which they filmed promotional clips for their soon-to-be-released “Strawberry Fields Forever / Penny Lane” single.

For demo purposes only, the first mono mix of the song as it stood so far was made on January 30th, 1967 in the control room of EMI Studio Three by George Martin, Geoff Emerick and Richard Lush. The Beatles were not in attendance, nor did they need to be. While this mix is an interesting listen, it was only created to allow the group to hear what was done and to help them decide what was further needed to complete the song.

For demo purposes only, the first mono mix of the song as it stood so far was made on January 30th, 1967 in the control room of EMI Studio Three by George Martin, Geoff Emerick and Richard Lush. The Beatles were not in attendance, nor did they need to be. While this mix is an interesting listen, it was only created to allow the group to hear what was done and to help them decide what was further needed to complete the song.

Session Three: Work resumed on “A Day In the Life” on February 3rd, 1967 in EMI Studio Two, the session indicated to have begun at 7 pm. The first overdub to be tackled on this day appears to have been replacing Paul’s guide vocal with the real thing, complete with heavy breathing from John after the words "I noticed I was late." “He and I had a long discussion about that,” Geoff Emerick explains, “which led to another sonic innovation. He explained that he wanted his voice to sound all muzzy, as if he had just woken up from a deep sleep and hadn’t yet gotten his bearings, because that was what the lyric was trying to convey. My way of achieving that was to deliberately remove a lot of the treble from his voice and heavily compress it to make him sound muffled. When the song goes into the next section, the dreamy section that John sings, the full fidelity is restored.”

Session Three: Work resumed on “A Day In the Life” on February 3rd, 1967 in EMI Studio Two, the session indicated to have begun at 7 pm. The first overdub to be tackled on this day appears to have been replacing Paul’s guide vocal with the real thing, complete with heavy breathing from John after the words "I noticed I was late." “He and I had a long discussion about that,” Geoff Emerick explains, “which led to another sonic innovation. He explained that he wanted his voice to sound all muzzy, as if he had just woken up from a deep sleep and hadn’t yet gotten his bearings, because that was what the lyric was trying to convey. My way of achieving that was to deliberately remove a lot of the treble from his voice and heavily compress it to make him sound muffled. When the song goes into the next section, the dreamy section that John sings, the full fidelity is restored.”

Editing in this vocal was quite tricky for Richard Lush, who had only just recently been recruited to work on Beatles sessions. Geoff Emerick continues: “Paul’s vocal…was being dropped into the same track that contained John’s lead vocal, and there was a very tight drop-out point between the two – between Paul’s singing ‘…and I went into a dream’ and John’s ‘ahhh’ that starts the next section. Richard (Lush) was quite paranoid about it – with good reason – and I remember him asking me to get on the talkback mic to explain the situation to Paul and ask him not to deviate from the phrasing that he had used on the guide vocal.”

Editing in this vocal was quite tricky for Richard Lush, who had only just recently been recruited to work on Beatles sessions. Geoff Emerick continues: “Paul’s vocal…was being dropped into the same track that contained John’s lead vocal, and there was a very tight drop-out point between the two – between Paul’s singing ‘…and I went into a dream’ and John’s ‘ahhh’ that starts the next section. Richard (Lush) was quite paranoid about it – with good reason – and I remember him asking me to get on the talkback mic to explain the situation to Paul and ask him not to deviate from the phrasing that he had used on the guide vocal.”

"I was really impressed when Richard (Lush) did that," Geoff Emerick continues in his book "Here, There And Everywhere." "I thought it showed great maturity to be proactive that way. John’s vocal, after all, had such great emotion, and it also had tape echo on it. The thought of having to do it again and re-create the atmosphere was daunting…not to mention what John’s reaction would have been! Someone’s head would have been bitten off, and it most likely would have been mine. But Paul, ever professional, did heed the warning, and he made certain to end the last word distinctly in order to give Richard (Lush) sufficient time to drop out before John’s vocal came back in. Listening carefully, you can actually hear Paul slightly rush the vocal; he even adds a little ‘ah’ to the end of the word ‘dream,’ giving it a very clipped ending.”

"I was really impressed when Richard (Lush) did that," Geoff Emerick continues in his book "Here, There And Everywhere." "I thought it showed great maturity to be proactive that way. John’s vocal, after all, had such great emotion, and it also had tape echo on it. The thought of having to do it again and re-create the atmosphere was daunting…not to mention what John’s reaction would have been! Someone’s head would have been bitten off, and it most likely would have been mine. But Paul, ever professional, did heed the warning, and he made certain to end the last word distinctly in order to give Richard (Lush) sufficient time to drop out before John’s vocal came back in. Listening carefully, you can actually hear Paul slightly rush the vocal; he even adds a little ‘ah’ to the end of the word ‘dream,’ giving it a very clipped ending.”

The above quote from Geoff Emerick, who was an eye-witness to the events on this day, clarifies that it was indeed John who sang the dreamy "aaah" vocal passage on the song. This should be enough to satisfy readers who insist that Paul sang this passage, their insistance being due to a passing comment from engineer Sam Okell during an interview five decades later that appears to indicate McCartney as singing this passage. Although Geoff Emerick had aged considerably by the time he wrote his book, credence should be given to his recollection since he was present at the time. Also, upon hearing the isolated vocal track that has been made available in various places, you can also hear other quieter voices appearing on the same track, including Paul's commonly used "oooooh" as heard throughout his career (such as on "Get Back," "Maybe I'm Amazed" and "The Back Seat Of My Car," to name just a few). The above quote indicates that John’s dreamy “aaah” vocal on the song must also have been recorded on this day, prior to Paul’s lead vocal section. This can confidently be said since the last day they worked on the song was on January 20th, 1967, this resulting in the "take six" mono mix of January 30th, which did not contain John’s vocals in that section.

The above quote from Geoff Emerick, who was an eye-witness to the events on this day, clarifies that it was indeed John who sang the dreamy "aaah" vocal passage on the song. This should be enough to satisfy readers who insist that Paul sang this passage, their insistance being due to a passing comment from engineer Sam Okell during an interview five decades later that appears to indicate McCartney as singing this passage. Although Geoff Emerick had aged considerably by the time he wrote his book, credence should be given to his recollection since he was present at the time. Also, upon hearing the isolated vocal track that has been made available in various places, you can also hear other quieter voices appearing on the same track, including Paul's commonly used "oooooh" as heard throughout his career (such as on "Get Back," "Maybe I'm Amazed" and "The Back Seat Of My Car," to name just a few). The above quote indicates that John’s dreamy “aaah” vocal on the song must also have been recorded on this day, prior to Paul’s lead vocal section. This can confidently be said since the last day they worked on the song was on January 20th, 1967, this resulting in the "take six" mono mix of January 30th, which did not contain John’s vocals in that section.

Speaking of the mono mix of January 20th, 1967, listening to it obviously persuaded the group that both the bass and drums could be improved upon. Paul re-recorded his entire bass part on this day, dropping the warbly playing and the “freak-out” section at the end as had been done during his first bass attempt. As for the drums, in his book “Many Years From Now,” Paul recounts: “We persuaded Ringo to play tom-toms. It’s sensational. He normally didn’t like to play lead drums, as it were, but we coached him through it. We said, ‘Come on, you’re fantastic, this will be really beautiful,’ and indeed it was.” Genesis drummer Phil Collins remarks, “The drum fills on ‘Day In The Life’ are very, very complex things. You know, you could take a great drummer from today and say, ‘I want it like that,’ and they really wouldn’t know what to do.”

Speaking of the mono mix of January 20th, 1967, listening to it obviously persuaded the group that both the bass and drums could be improved upon. Paul re-recorded his entire bass part on this day, dropping the warbly playing and the “freak-out” section at the end as had been done during his first bass attempt. As for the drums, in his book “Many Years From Now,” Paul recounts: “We persuaded Ringo to play tom-toms. It’s sensational. He normally didn’t like to play lead drums, as it were, but we coached him through it. We said, ‘Come on, you’re fantastic, this will be really beautiful,’ and indeed it was.” Genesis drummer Phil Collins remarks, “The drum fills on ‘Day In The Life’ are very, very complex things. You know, you could take a great drummer from today and say, ‘I want it like that,’ and they really wouldn’t know what to do.”

Geoff Emerick gives an interesting account of this drum overdub: “Paul suggested that Ringo not just do his normal turn but really cut loose on the track, and I could see that the drummer was quite reticent. ‘Come on, Paul, you know how much I hate flashy drumming,’ he complained, but with John and Paul coaching and egging him on, he did an overdub that was nothing short of spectacular, featuring a whole series of quirky tom-tom fills.”

Geoff Emerick gives an interesting account of this drum overdub: “Paul suggested that Ringo not just do his normal turn but really cut loose on the track, and I could see that the drummer was quite reticent. ‘Come on, Paul, you know how much I hate flashy drumming,’ he complained, but with John and Paul coaching and egging him on, he did an overdub that was nothing short of spectacular, featuring a whole series of quirky tom-tom fills.”

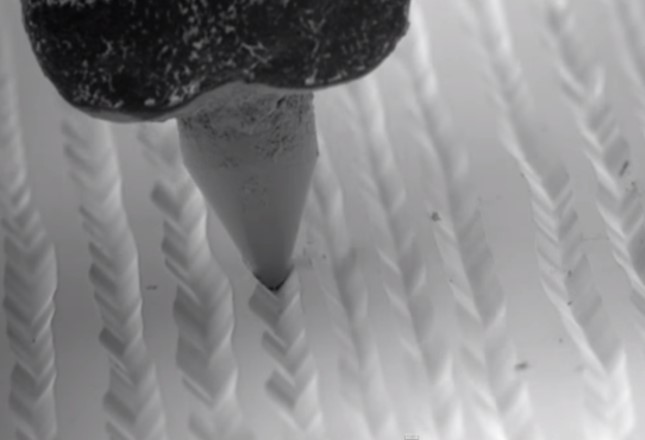

"Because John and Paul felt so strongly that the drums be featured in this song. I decided to experiment sonically as well. We were looking for a thicker, more tonal quality, so I suggested that Ringo tune his toms really low, making the skins really slack, and I also added a lot of low end at the mixing console. That made them sound almost like timpani, but I still felt there was more I could do to make his playing stand out. During the making of ‘Revolver,’ I had removed the front skin from Ringo’s bass drum and everyone was pleased with the resultant sound, so I decided to extend that principle and take off the bottom heads from the tom-toms as well, miking them from underneath. We had no boom stands that could extend underneath the floor tom, so I simply wrapped the mic in a towel and placed it in a glass jug on the floor. For the icing on the cake, I decided to overly limit the drum premix, which made the cymbals sound huge. It took a lot of work and effort, but that’s one drum sound I was extremely proud of, and Ringo, who was always meticulous about his sounds, loved it, too.”

"Because John and Paul felt so strongly that the drums be featured in this song. I decided to experiment sonically as well. We were looking for a thicker, more tonal quality, so I suggested that Ringo tune his toms really low, making the skins really slack, and I also added a lot of low end at the mixing console. That made them sound almost like timpani, but I still felt there was more I could do to make his playing stand out. During the making of ‘Revolver,’ I had removed the front skin from Ringo’s bass drum and everyone was pleased with the resultant sound, so I decided to extend that principle and take off the bottom heads from the tom-toms as well, miking them from underneath. We had no boom stands that could extend underneath the floor tom, so I simply wrapped the mic in a towel and placed it in a glass jug on the floor. For the icing on the cake, I decided to overly limit the drum premix, which made the cymbals sound huge. It took a lot of work and effort, but that’s one drum sound I was extremely proud of, and Ringo, who was always meticulous about his sounds, loved it, too.”

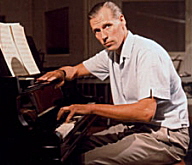

It was on this day, no doubt after the overdubs were complete, that a monumental decision was being made. In his book "All You Need Is Ears," George Martin explains: “The question was, how were we going to fill those twenty-four bars of emptiness? After all, it was pretty boring! So I asked John for his ideas. As always, it was a matter of my trying to get inside his mind, discover what pictures he wanted to paint, and then try to realize them for him…John said, ‘I want it to be like a musical orgasm…What I’d like to hear is a tremendous build-up, from nothing up to something absolutely like the end of the world. I’d like it to be from extreme quietness to extreme loudness, not only in volume, but also for the sound to expand as well. I’d like to use a symphony orchestra for it. Tell you what, George, you book a symphony orchestra, and we’ll get them in a studio and tell them what to do.’”

It was on this day, no doubt after the overdubs were complete, that a monumental decision was being made. In his book "All You Need Is Ears," George Martin explains: “The question was, how were we going to fill those twenty-four bars of emptiness? After all, it was pretty boring! So I asked John for his ideas. As always, it was a matter of my trying to get inside his mind, discover what pictures he wanted to paint, and then try to realize them for him…John said, ‘I want it to be like a musical orgasm…What I’d like to hear is a tremendous build-up, from nothing up to something absolutely like the end of the world. I’d like it to be from extreme quietness to extreme loudness, not only in volume, but also for the sound to expand as well. I’d like to use a symphony orchestra for it. Tell you what, George, you book a symphony orchestra, and we’ll get them in a studio and tell them what to do.’”

Paul goes on record to say that he had a big part in the “musical orgasm” idea: “I sat John down and suggested it to him and he liked it a lot. I said, ‘Look, all these composers are doing really weird avant-garde things and what I’d like to do here is give the orchestra some really strange instructions. We could tell them to sit there and be quiet, but that’s been done, or we could have our own ideas based on this school of thought. This is what’s going on now, this is what the movement’s about.’ So this is what we did.”

George Martin continues: “’Come on, John,’ I said, ‘there’s no way you can get a symphony orchestra sitting around and say to them, “Look fellers, this is what you’re going to do.” Because you won’t get them to do what you want them to do. You’ve got to write something down for them.’ ‘Why?,’ asked John, with his typically wide-eyed approach to such matters. ‘Because they’re all playing different instruments, and unless you’ve got time to go round each of them individually and see exactly what they do, it just won’t work.’”

George Martin continues: “’Come on, John,’ I said, ‘there’s no way you can get a symphony orchestra sitting around and say to them, “Look fellers, this is what you’re going to do.” Because you won’t get them to do what you want them to do. You’ve got to write something down for them.’ ‘Why?,’ asked John, with his typically wide-eyed approach to such matters. ‘Because they’re all playing different instruments, and unless you’ve got time to go round each of them individually and see exactly what they do, it just won’t work.’”

Geoff Emerick adds to the story: “George Martin liked the idea, but, mindful of the cost, was adamant that there was no way he could justify charging EMI for a full ninety-piece orchestra just to play twenty-four bars of music. It was Ringo, of all people, who came up with the solution. ‘Well, then,’ he joked, ‘let’s just hire half an orchestra and have them play it twice.’ Everyone did a double take, stunned by the simplicity – or was it simple-mindedness? – of the suggestion. ‘You know, Ring, that’s not a bad idea,’ Paul said. ‘But still, boys, think of the cost…’ George Martin stammered. Lennon put an end to the discussion, ‘Right, Henry,’ he said, his voice carrying the tone of an emperor issuing a decree. ‘Enough chitchat, let’s do it.’”

Geoff Emerick adds to the story: “George Martin liked the idea, but, mindful of the cost, was adamant that there was no way he could justify charging EMI for a full ninety-piece orchestra just to play twenty-four bars of music. It was Ringo, of all people, who came up with the solution. ‘Well, then,’ he joked, ‘let’s just hire half an orchestra and have them play it twice.’ Everyone did a double take, stunned by the simplicity – or was it simple-mindedness? – of the suggestion. ‘You know, Ring, that’s not a bad idea,’ Paul said. ‘But still, boys, think of the cost…’ George Martin stammered. Lennon put an end to the discussion, ‘Right, Henry,’ he said, his voice carrying the tone of an emperor issuing a decree. ‘Enough chitchat, let’s do it.’”

With the ball thrown into George Martin’s court, the recording session was complete for the day at 1:15 am the following morning. With the weekend off, George Martin undoubtedly began his plan to carry out John’s wishes.

Session Four: A week had gone by since the decision to use an orchestra had been finalized. While George Martin was busy with recording sessions for two new Beatles songs during the week, namely “Good Morning Good Morning” and “Fixing A Hole,” he was also working out all of the details in preparation for the orchestra session, which was arranged for February 10th, 1967. The cavernous EMI Studio One was booked this time, since it was almost always used for classical recordings and could accommodate symphony orchestras.

Session Four: A week had gone by since the decision to use an orchestra had been finalized. While George Martin was busy with recording sessions for two new Beatles songs during the week, namely “Good Morning Good Morning” and “Fixing A Hole,” he was also working out all of the details in preparation for the orchestra session, which was arranged for February 10th, 1967. The cavernous EMI Studio One was booked this time, since it was almost always used for classical recordings and could accommodate symphony orchestras.

Although it was John’s request to have them improvise, George Martin knew that wouldn’t fly with session musicians of this caliber. Therefore, he knew he had to put something together for them, which he did sometime within the previous week. “He did explain what he wanted sufficiently for me to be able to write a score,” George Martin explains. “For the ‘…turn you onnnnnnn…’ bit, I used cellos and violas. I had them playing those two notes that echo John’s voice. However, instead of fingering their instruments, which would produce crisp notes, I got them to slide their fingers up and down the frets, building in intensity until the start of the orchestral climax.”

Although it was John’s request to have them improvise, George Martin knew that wouldn’t fly with session musicians of this caliber. Therefore, he knew he had to put something together for them, which he did sometime within the previous week. “He did explain what he wanted sufficiently for me to be able to write a score,” George Martin explains. “For the ‘…turn you onnnnnnn…’ bit, I used cellos and violas. I had them playing those two notes that echo John’s voice. However, instead of fingering their instruments, which would produce crisp notes, I got them to slide their fingers up and down the frets, building in intensity until the start of the orchestral climax.”

"That climax was something else again. What I did there was to write, at the beginning of the twenty-four bars, the lowest possible note for each of the instruments in the orchestra. At the end of the twenty-four bars, I wrote the highest note each instrument could reach that was near a chord of E major. Then I put a squiggly line right through the twenty-four bars, with reference points to tell them roughly what note they should have reached during each bar…I marked the music ‘pianissimo’ at the beginning and ‘fortissimo’ at the end. Everyone was to start as quietly as possible, almost inaudibly, and end in a (metaphorically) lung-bursting tumult."

"That climax was something else again. What I did there was to write, at the beginning of the twenty-four bars, the lowest possible note for each of the instruments in the orchestra. At the end of the twenty-four bars, I wrote the highest note each instrument could reach that was near a chord of E major. Then I put a squiggly line right through the twenty-four bars, with reference points to tell them roughly what note they should have reached during each bar…I marked the music ‘pianissimo’ at the beginning and ‘fortissimo’ at the end. Everyone was to start as quietly as possible, almost inaudibly, and end in a (metaphorically) lung-bursting tumult."

There was one more section that needed a score written out for, Paul apparently having had a part in this. He explains: “We wrote out the music for the part where the orchestra had proper chords to do: after ‘somebody spoke and I went into a dream…’ big pure chords come in.”

Additional preparation was needed and arranged for proceeding with the day’s session. “We all felt a sense of occasion, since it was the largest orchestra we ever used on a Beatles recording,” George Martin continues. “So I wasn’t all that surprised when Paul rang up and said, ‘Look, do you mind coming in evening dress?’ ‘Why? What’s the idea?’ ‘We thought we’d have fun. We’ve never had a big orchestra before, so we thought we’d have fun on the night. So will you come in evening dress? And I’d like all the orchestra to come in evening dress, too.’ ‘Well, that may cost a bit extra, but we’ll do it,’ I said. ‘What are you going to wear?’ ‘Oh, our usual freak-outs’ – by which he meant their gaudy hippie clothes, floral coats and all.”

Additional preparation was needed and arranged for proceeding with the day’s session. “We all felt a sense of occasion, since it was the largest orchestra we ever used on a Beatles recording,” George Martin continues. “So I wasn’t all that surprised when Paul rang up and said, ‘Look, do you mind coming in evening dress?’ ‘Why? What’s the idea?’ ‘We thought we’d have fun. We’ve never had a big orchestra before, so we thought we’d have fun on the night. So will you come in evening dress? And I’d like all the orchestra to come in evening dress, too.’ ‘Well, that may cost a bit extra, but we’ll do it,’ I said. ‘What are you going to wear?’ ‘Oh, our usual freak-outs’ – by which he meant their gaudy hippie clothes, floral coats and all.”

Barry Miles, friend and co-author of Paul’s “Many Years From Now” book, describes the scene in the studio that day, February 10th, 1967, starting at 8 pm. “The studio was filled with balloons, and flower children in tattered lace and faded velvet tripped around the room blowing rainbow bubbles. Three Rolling Stones – Brian Jones, Keith Richards and Mick Jagger – accompanied by Marianne Faithfull paraded in King’s Road psychedelic finery, with flowing scarves, crushed velvet and satin trousers and multicolored boots. In the Mal Evans biography "Living The Beatles Legend," author Kenneth Womack reveals that Mal's diary entry for this day was "LIGHTS! CAMERAS! ACTION! BALLOONS?"

Barry Miles, friend and co-author of Paul’s “Many Years From Now” book, describes the scene in the studio that day, February 10th, 1967, starting at 8 pm. “The studio was filled with balloons, and flower children in tattered lace and faded velvet tripped around the room blowing rainbow bubbles. Three Rolling Stones – Brian Jones, Keith Richards and Mick Jagger – accompanied by Marianne Faithfull paraded in King’s Road psychedelic finery, with flowing scarves, crushed velvet and satin trousers and multicolored boots. In the Mal Evans biography "Living The Beatles Legend," author Kenneth Womack reveals that Mal's diary entry for this day was "LIGHTS! CAMERAS! ACTION! BALLOONS?"

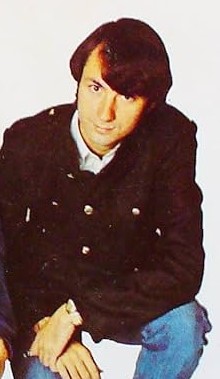

Donovan, the cosmic troubadour, Graham Nash, the only psychedelic member of The Hollies, the Monkee Mike Nesmith, Patti Harrison (George’s wife) and dozens of other friends milled around the edge of the room. The four Dutch designers known as The Fool arrived dressed as characters from the Tarot, carrying tambourines and bells, while the mighty Abbey Road air conditioners worked hard to control the rich fragrance of joss sticks and marijuana.” Interestingly, the tambourine playing of Marijke Koger of The Fool was caught on tape during this session and actually appears on the released recording.

Donovan, the cosmic troubadour, Graham Nash, the only psychedelic member of The Hollies, the Monkee Mike Nesmith, Patti Harrison (George’s wife) and dozens of other friends milled around the edge of the room. The four Dutch designers known as The Fool arrived dressed as characters from the Tarot, carrying tambourines and bells, while the mighty Abbey Road air conditioners worked hard to control the rich fragrance of joss sticks and marijuana.” Interestingly, the tambourine playing of Marijke Koger of The Fool was caught on tape during this session and actually appears on the released recording.

During the recording sessions of the previous week, discussions ensued between John, Paul and the engineering staff as to what would transpire on this orchestral session. During these discussions, John came up with an idea intended to get the orchestra musicians to cooperate. Geoff Emerick relates the details about one of these conversations: “John seemed lost in thought for a moment, and then brightened up. ‘Well, if we put them in silly party hats and rubber noses, maybe then they’ll understand what it is we want. That will loosen up those tight-asses!’ I thought it was a brilliant idea. The idea was to get them into the spirit of things, to create a party atmosphere, a sense of camaraderie. John was not seeking to necessarily embarrass them or make them look silly – he was actually trying to tear down the barrier that had existed between classical and pop musicians for years…To gales of laughter from the others, Lennon began reeling off a list of what he wanted Mal (Evans) to purchase at the novelty store: silly hats, rubber noses, clown wigs, bald head pates, gorilla paws…and lots of clip-on nipples.”

During the recording sessions of the previous week, discussions ensued between John, Paul and the engineering staff as to what would transpire on this orchestral session. During these discussions, John came up with an idea intended to get the orchestra musicians to cooperate. Geoff Emerick relates the details about one of these conversations: “John seemed lost in thought for a moment, and then brightened up. ‘Well, if we put them in silly party hats and rubber noses, maybe then they’ll understand what it is we want. That will loosen up those tight-asses!’ I thought it was a brilliant idea. The idea was to get them into the spirit of things, to create a party atmosphere, a sense of camaraderie. John was not seeking to necessarily embarrass them or make them look silly – he was actually trying to tear down the barrier that had existed between classical and pop musicians for years…To gales of laughter from the others, Lennon began reeling off a list of what he wanted Mal (Evans) to purchase at the novelty store: silly hats, rubber noses, clown wigs, bald head pates, gorilla paws…and lots of clip-on nipples.”

“As everyone began tuning up, Mal (Evans) started circulating among the musicians, handing out pary favors. ‘Here you go, mate, have one of these,’ he would say amiably in his working-class Liverpool accent, rubber nose or fake boob in hand…Most of them ended up donning hats, gorilla paws, and the like, though I suspect they probably would have been a little more resistant if it wasn’t for the fact that Mal was six foot four and weighed well over two hundred pounds.”

“As everyone began tuning up, Mal (Evans) started circulating among the musicians, handing out pary favors. ‘Here you go, mate, have one of these,’ he would say amiably in his working-class Liverpool accent, rubber nose or fake boob in hand…Most of them ended up donning hats, gorilla paws, and the like, though I suspect they probably would have been a little more resistant if it wasn’t for the fact that Mal was six foot four and weighed well over two hundred pounds.”

George Martin remembers: “After one of the rehearsals I went into the control room to consult Geoff Emerick. When I went back into the studio the sight was unbelievable. The orchestra leader, David McCallum, who used to be the leader of the Royal Philharmonic, was sitting there in a bright red false nose. He looked up at me through paper glasses. Erich Gruenberg, now a soloist and once leader of the BBC Symphony Orchestra, was playing happily away, his left hand perfectly normal on the strings of his violin, but his bow held in a giant gorilla’s paw. Every member of the orchestra had a funny hat on above the evening dress, and the total effect was completely weird.”

George Martin remembers: “After one of the rehearsals I went into the control room to consult Geoff Emerick. When I went back into the studio the sight was unbelievable. The orchestra leader, David McCallum, who used to be the leader of the Royal Philharmonic, was sitting there in a bright red false nose. He looked up at me through paper glasses. Erich Gruenberg, now a soloist and once leader of the BBC Symphony Orchestra, was playing happily away, his left hand perfectly normal on the strings of his violin, but his bow held in a giant gorilla’s paw. Every member of the orchestra had a funny hat on above the evening dress, and the total effect was completely weird.”

Personal attention needed to be made to each musician, something Paul personally helped George Martin to do. “So we had to go round and talk to them all,” Paul explained, “seeing them all separate: ‘Wot’s all this, Paul? What exactly d’you…’ ‘In your own speed…’ ‘What do you mean, any way I want?’ ‘Yeah.’ The trumpets got the idea rather easily. ‘You can do it all in one spurt if you like. But you can’t go back. You’ve got to end at your top note, or have done your top note.’…All the strings went together like sheep, all looked at each other to see who was going up…Trumpets had no such reservations whatsoever, trumpets are notoriously the guys who go to the pub because you need to wet your whistle, you need plenty of spittle. So they were very free.”

Personal attention needed to be made to each musician, something Paul personally helped George Martin to do. “So we had to go round and talk to them all,” Paul explained, “seeing them all separate: ‘Wot’s all this, Paul? What exactly d’you…’ ‘In your own speed…’ ‘What do you mean, any way I want?’ ‘Yeah.’ The trumpets got the idea rather easily. ‘You can do it all in one spurt if you like. But you can’t go back. You’ve got to end at your top note, or have done your top note.’…All the strings went together like sheep, all looked at each other to see who was going up…Trumpets had no such reservations whatsoever, trumpets are notoriously the guys who go to the pub because you need to wet your whistle, you need plenty of spittle. So they were very free.”

“The musicians also had instructions to slide as gracefully as possible between one note and the next,” remembers George Martin. “In the case of the stringed instruments, that was a matter of sliding their fingers up the strings. With keyed instruments, like clarinet and oboe, they obviously had to move their fingers from key to key as they went up, but they were asked to ‘lip’ the changes as much as possible too… And in addition to this extraordinary piece of musical gymnastics, I told them that they were to disobey the most fundamental rule of the orchestra. They were not to listen to their neighbors. A well-schooled orchestra plays, ideally, like one man, following the leader. I emphasized that this was exactly what they must not do. I told them, ‘I want everyone to be individual. It’s every man for himself. Don’t listen to the fellow next to you. If he’s a third away from you, and you think he’s going to fast, let him go. Just do your own slide up, your own way.’ Needless to say, they were amazed. They had certainly never been told that before.”

“The musicians also had instructions to slide as gracefully as possible between one note and the next,” remembers George Martin. “In the case of the stringed instruments, that was a matter of sliding their fingers up the strings. With keyed instruments, like clarinet and oboe, they obviously had to move their fingers from key to key as they went up, but they were asked to ‘lip’ the changes as much as possible too… And in addition to this extraordinary piece of musical gymnastics, I told them that they were to disobey the most fundamental rule of the orchestra. They were not to listen to their neighbors. A well-schooled orchestra plays, ideally, like one man, following the leader. I emphasized that this was exactly what they must not do. I told them, ‘I want everyone to be individual. It’s every man for himself. Don’t listen to the fellow next to you. If he’s a third away from you, and you think he’s going to fast, let him go. Just do your own slide up, your own way.’ Needless to say, they were amazed. They had certainly never been told that before.”

George Martin began to get quite frustrated explaining what was needed from the musicians.“’Do what?? What the bloody hell…?’” was heard by Geoff Emerick as he eavesdropped on a conversation between George Martin and Erich Gruenberg, which resulted in the reassurance “’Just trust me. Please. Just Trust Me’” as balloons kept popping in the background.

Actually recording the performance was a big challenge as well. "Three of the four tracks of the multitrack master were already filled with overdubs," Geoff Emerick adds, "and I knew we’d be having the orchestra play at least twice all the way through, so the one remaining track clearly wouldn’t be sufficient. One option was doing a mono premix, but that meant taking the recording down another generation, and we’d already done several reductions, so I really didn’t want to do that. Another option was to utilize a second four-track machine for recording the orchestra, using the original tape for playback only. That would give us four additional tracks to record on, but the problem there was synchronization; we needed to find a way to lock the two machines together so that they ran at exactly the same speed – something that had never been done before, at least not at EMI."

Actually recording the performance was a big challenge as well. "Three of the four tracks of the multitrack master were already filled with overdubs," Geoff Emerick adds, "and I knew we’d be having the orchestra play at least twice all the way through, so the one remaining track clearly wouldn’t be sufficient. One option was doing a mono premix, but that meant taking the recording down another generation, and we’d already done several reductions, so I really didn’t want to do that. Another option was to utilize a second four-track machine for recording the orchestra, using the original tape for playback only. That would give us four additional tracks to record on, but the problem there was synchronization; we needed to find a way to lock the two machines together so that they ran at exactly the same speed – something that had never been done before, at least not at EMI."

In the book “The Beatles Recording Sessions,” engineer Ken Townsend relates: “George Martin came up to me that morning and said to me, ‘Oh Ken, I’ve got a poser for you. I want to run two four-track tape machines together this evening. I know it’s never been done before, can you do it?’ So I went away and came up with a method whereby we fed a 50 cycle tone from the track of one machine then raised its voltage to drive the capstan motor of the second, thus running the two in sync. Like all these things, the ideas either work first time or not at all. This one worked first time. At the session we ran the Beatles’ rhythm track on one machine, put an orchestral track on the second machine, ran it back did it again, and again, and again until we had four orchestra recordings.”

In the book “The Beatles Recording Sessions,” engineer Ken Townsend relates: “George Martin came up to me that morning and said to me, ‘Oh Ken, I’ve got a poser for you. I want to run two four-track tape machines together this evening. I know it’s never been done before, can you do it?’ So I went away and came up with a method whereby we fed a 50 cycle tone from the track of one machine then raised its voltage to drive the capstan motor of the second, thus running the two in sync. Like all these things, the ideas either work first time or not at all. This one worked first time. At the session we ran the Beatles’ rhythm track on one machine, put an orchestral track on the second machine, ran it back did it again, and again, and again until we had four orchestra recordings.”

Geoff Emerick continues: “Finally a rehearsal was called – or so the musicians thought. We had made a decision beforehand that we would roll tape for every attempt at playing the twenty-four-bar climb, whether it was a proper take or just a rehearsal. This was partially because of the technical challenges – we knew that the two machines would not run in sync every time we attempted it, so we wanted to maximize our chances – and partially because we were doing something naughty. Ever conscious of cost, George Martin had warned Richard and me not to let the musicians know we would be recording them multiple times on separate tracks, because doing so would result in massive extra charges. Instead, we were under strict instructions to make them think that each time around we were wiping the previous take and recording over it. But, of course, we weren’t; over the remaining two and a half hours of the session, we actually recorded them playing that passage eight separate times, on two clean sections of four-track tape.”

Geoff Emerick continues: “Finally a rehearsal was called – or so the musicians thought. We had made a decision beforehand that we would roll tape for every attempt at playing the twenty-four-bar climb, whether it was a proper take or just a rehearsal. This was partially because of the technical challenges – we knew that the two machines would not run in sync every time we attempted it, so we wanted to maximize our chances – and partially because we were doing something naughty. Ever conscious of cost, George Martin had warned Richard and me not to let the musicians know we would be recording them multiple times on separate tracks, because doing so would result in massive extra charges. Instead, we were under strict instructions to make them think that each time around we were wiping the previous take and recording over it. But, of course, we weren’t; over the remaining two and a half hours of the session, we actually recorded them playing that passage eight separate times, on two clean sections of four-track tape.”

Friend Pete Shotton, who was also in attendance on the day, recounts another element of the session: “The twist was added during the taping of the cosmic crescendo on ‘A Day In The Life,’ for which Paul has assumed, with obvious relish, the role of conductor.” Paul remembers: “I felt initially embarrassed facing that sea of sessioners. So, I decided to treat them like human beings and not professional musicians. I tried to give myself to them.”

Friend Pete Shotton, who was also in attendance on the day, recounts another element of the session: “The twist was added during the taping of the cosmic crescendo on ‘A Day In The Life,’ for which Paul has assumed, with obvious relish, the role of conductor.” Paul remembers: “I felt initially embarrassed facing that sea of sessioners. So, I decided to treat them like human beings and not professional musicians. I tried to give myself to them.”

Geoff Emerick gives some more detail: “As the evening wore on, Paul decided to have a go at conducting, too, and despite his inexperience he did quite a good job. They took slightly different approaches: George (Martin) imparted a little more instruction than Paul did, giving the musicians little signposts along the way, while Paul urged them to play more free-form. The combination and contrast between the two different styles made for an interesting sonic experience when we finally listened back to the tracks – well after the musicians had packed up and left for the night.”

Geoff Emerick gives some more detail: “As the evening wore on, Paul decided to have a go at conducting, too, and despite his inexperience he did quite a good job. They took slightly different approaches: George (Martin) imparted a little more instruction than Paul did, giving the musicians little signposts along the way, while Paul urged them to play more free-form. The combination and contrast between the two different styles made for an interesting sonic experience when we finally listened back to the tracks – well after the musicians had packed up and left for the night.”

As for the activities of the other Beatles, Geoff Emerick adds: “Through all the hubbub, a mellowed-out John was just wandering around in a daze. He, Paul, and George Martin popped into the control room to hear the first playback or two; other than that, they spent the entire evening in the studio along with George Harrison, Ringo, and their guests.”

And finally, the orchestral overdub was complete. Geoff Emerick states, “As George Martin put down his baton and said, ‘Thank you, gentlemen, that’s a wrap,’ everyone in the entire studio – orchestra members, Beatles, and Beatles friends alike – broke into spontaneous applause. It was a hell of a moment, and the perfect ending to a remarkable session." This isolated orchestra overdub can be heard, along with The Beatles recording thus far playing quietly through the studio monitors, on the "Super Deluxe Edition" box set of the 50th Anniversary release of the "Sgt. Pepper" album.

And finally, the orchestral overdub was complete. Geoff Emerick states, “As George Martin put down his baton and said, ‘Thank you, gentlemen, that’s a wrap,’ everyone in the entire studio – orchestra members, Beatles, and Beatles friends alike – broke into spontaneous applause. It was a hell of a moment, and the perfect ending to a remarkable session." This isolated orchestra overdub can be heard, along with The Beatles recording thus far playing quietly through the studio monitors, on the "Super Deluxe Edition" box set of the 50th Anniversary release of the "Sgt. Pepper" album.

At this point, however, the song ended with the orchestra reaching the high E major chord. Paul had another idea brewing in his head on this day. “Paul asked the other Beatles and their guests to stick around,” Geoff Emerick remembers, “and try out an idea he had just gotten for an ending, something he wanted to overdub on after the final orchestral climax. Everyone was weary – the studio was starting to smell suspiciously of pot, and there was lots of wine floating around – but they were keen to have a go. Paul’s concept was to have everyone hum the same note in unison; it was the kind of avant-garde thinking he was doing a lot of in those days. It was absurd, really – the biggest gathering of pop stars in the world, gathered around a microphone, humming, with Paul conducting the choir…It was a fun way to cap off a fine party.”

At this point, however, the song ended with the orchestra reaching the high E major chord. Paul had another idea brewing in his head on this day. “Paul asked the other Beatles and their guests to stick around,” Geoff Emerick remembers, “and try out an idea he had just gotten for an ending, something he wanted to overdub on after the final orchestral climax. Everyone was weary – the studio was starting to smell suspiciously of pot, and there was lots of wine floating around – but they were keen to have a go. Paul’s concept was to have everyone hum the same note in unison; it was the kind of avant-garde thinking he was doing a lot of in those days. It was absurd, really – the biggest gathering of pop stars in the world, gathered around a microphone, humming, with Paul conducting the choir…It was a fun way to cap off a fine party.”

Mark Lewisohn got a listen to these humming takes in the making of his book “The Beatles Recording Sessions.” He writes: “The Beatles and various friends (at least one female voice is evident) gathered around the studio microphone and attempted to record the song’s coda…which at this stage was going to be a long ‘hummmmmmm.’ ‘Eight beats, remember’ says Paul, leading them into the first take of this edit piece. This and two others (numbered eight to ten) dissolved, understandably, into laughter. But 'take 11' was good so onto this the ensemble recorded three overdubs, filling the four-track tape. It was undoubtedly a fine idea, and it was to remain the best solution to ending the song until the famous piano chord was recorded.”

Mark Lewisohn got a listen to these humming takes in the making of his book “The Beatles Recording Sessions.” He writes: “The Beatles and various friends (at least one female voice is evident) gathered around the studio microphone and attempted to record the song’s coda…which at this stage was going to be a long ‘hummmmmmm.’ ‘Eight beats, remember’ says Paul, leading them into the first take of this edit piece. This and two others (numbered eight to ten) dissolved, understandably, into laughter. But 'take 11' was good so onto this the ensemble recorded three overdubs, filling the four-track tape. It was undoubtedly a fine idea, and it was to remain the best solution to ending the song until the famous piano chord was recorded.”

In a sequence that was cut from the “Anthology” documentary, George Martin explains the “hum” overdub a little differently: “We still needed a finisher, though, and it had to be something that wasn’t orchestral – we had already done that. And this was one of those bright ideas that just didn’t work. We thought of all the ideas of Buddhist monks chanting. We thought it’d be a great idea to have everybody messed in the studio doing “Ommmm,” hanging onto it, and multiply it many times. And the result was – pathetic!” These 'takes' of the hummed last chord can be heard on various editions of the 50th Anniversary releases of the "Sgt. Pepper" album. Upon hearing them, we can’t help but notice the similarity between this and what The Moody Blues performed the following year in their song “Om” from the album “In Search Of The Lost Chord.”

In a sequence that was cut from the “Anthology” documentary, George Martin explains the “hum” overdub a little differently: “We still needed a finisher, though, and it had to be something that wasn’t orchestral – we had already done that. And this was one of those bright ideas that just didn’t work. We thought of all the ideas of Buddhist monks chanting. We thought it’d be a great idea to have everybody messed in the studio doing “Ommmm,” hanging onto it, and multiply it many times. And the result was – pathetic!” These 'takes' of the hummed last chord can be heard on various editions of the 50th Anniversary releases of the "Sgt. Pepper" album. Upon hearing them, we can’t help but notice the similarity between this and what The Moody Blues performed the following year in their song “Om” from the album “In Search Of The Lost Chord.”

As the time neared 1 am the following morning, everyone present was understandably curious as to how the day’s recording came out. Geoff Emerick relates: “Everyone crowded into the tiny control room for one last playback, the overflow of guests spilling out into the corridor, listening through the open door. Everyone, without exception, was totally and utterly blown away by what they were hearing; Ron Richards kept shaking his head, telling anyone who would listen, ‘That’s it, I think I’ll give up and retire now.’”

As the time neared 1 am the following morning, everyone present was understandably curious as to how the day’s recording came out. Geoff Emerick relates: “Everyone crowded into the tiny control room for one last playback, the overflow of guests spilling out into the corridor, listening through the open door. Everyone, without exception, was totally and utterly blown away by what they were hearing; Ron Richards kept shaking his head, telling anyone who would listen, ‘That’s it, I think I’ll give up and retire now.’”

After the weekend off, the group reassembled in EMI Studio Two the following Monday, February 13th, 1967, to start work on what was to be George Harrison’s contribution to the “Sgt. Pepper” album, namely “Only A Northern Song” (which, of course, didn’t make the cut). Before this began, however, they couldn’t help but try their hand at creating a mono mix for “A Day In The Life,” no doubt with the “hummmmmm” ending. Four attempts were made (indicated as remixes 2 through 5) by the engineering staff of George Martin, Geoff Emerick and Richard Lush with input from The Beatles undoubtedly, although these mono mixes have never seen the light of day.

After the weekend off, the group reassembled in EMI Studio Two the following Monday, February 13th, 1967, to start work on what was to be George Harrison’s contribution to the “Sgt. Pepper” album, namely “Only A Northern Song” (which, of course, didn’t make the cut). Before this began, however, they couldn’t help but try their hand at creating a mono mix for “A Day In The Life,” no doubt with the “hummmmmm” ending. Four attempts were made (indicated as remixes 2 through 5) by the engineering staff of George Martin, Geoff Emerick and Richard Lush with input from The Beatles undoubtedly, although these mono mixes have never seen the light of day.

Session Five: By February 22nd, 1967, it was decided that the “hummmmmm” ending wasn’t quite good enough to end the song, thereby ending the album. “The inspiration for what was finally used once again came from Paul,” Geoff Emerick relates, "with eager assent from John: a huge piano chord that would last ‘forever’…or at least as long as I could figure out how to get the sound to sustain…tape hiss and vinyl surface noise would obliterate any low-level signal all too soon. It seemed clear to me that the solution lay in keeping the sound at maximum volume for as long as possible, and I had two weapons that could accomplish this: a compressor, cranked up full, and the very faders themselves on the mixing console. Logically, if I set the gain of each input to maximum but started with the fader at its lowest point, I could then slowly raise the faders as the sound died away, thus compensating for the loss in volume: in effect, I could counteract the chord getting softer, at least to some degree."

Session Five: By February 22nd, 1967, it was decided that the “hummmmmm” ending wasn’t quite good enough to end the song, thereby ending the album. “The inspiration for what was finally used once again came from Paul,” Geoff Emerick relates, "with eager assent from John: a huge piano chord that would last ‘forever’…or at least as long as I could figure out how to get the sound to sustain…tape hiss and vinyl surface noise would obliterate any low-level signal all too soon. It seemed clear to me that the solution lay in keeping the sound at maximum volume for as long as possible, and I had two weapons that could accomplish this: a compressor, cranked up full, and the very faders themselves on the mixing console. Logically, if I set the gain of each input to maximum but started with the fader at its lowest point, I could then slowly raise the faders as the sound died away, thus compensating for the loss in volume: in effect, I could counteract the chord getting softer, at least to some degree."