Search by Keyword

Sign Up Below for our MONTHLY BEATLES TRIVIA QUIZ!

|

“RUN FOR YOUR LIFE”

(John Lennon – Paul McCartney)

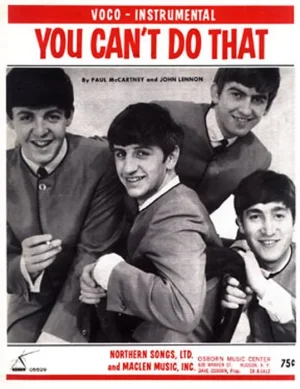

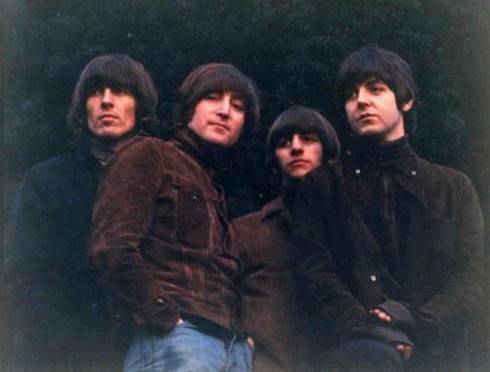

Jealousy was not a subject that was foreign to compositions of John Lennon during The Beatles years. In 1964’s “You Can’t Do That,” for instance, John threatens that if his girl is caught talking to another man he’s ‘gonna let her down and leave her flat.’ If that sounds harsh, John takes it much further in 1965’s “Run For Your Life.” This time, the singer sneers that “he’s determined” to do something much more drastic if his woman is caught “with another man.” “I’d rather see you dead” John reveals, and not by any other hand than his own. Jealousy was not a subject that was foreign to compositions of John Lennon during The Beatles years. In 1964’s “You Can’t Do That,” for instance, John threatens that if his girl is caught talking to another man he’s ‘gonna let her down and leave her flat.’ If that sounds harsh, John takes it much further in 1965’s “Run For Your Life.” This time, the singer sneers that “he’s determined” to do something much more drastic if his woman is caught “with another man.” “I’d rather see you dead” John reveals, and not by any other hand than his own.

These murderous lyrics went mostly unnoticed when the song was first released, the focus being on the clever harmonies and the recurring use of the phrase “little girl.” Most viewed it as a fun-loving sing-along with a catchy melody line. Many artists, such as Gary Lewis and The Playboys and Nancy Sinatra, were quick to record cover versions. It was only later that, when analyzed, it dawned on authors, commentators and fans alike that Lennon was actually threatening to kill his lover. These murderous lyrics went mostly unnoticed when the song was first released, the focus being on the clever harmonies and the recurring use of the phrase “little girl.” Most viewed it as a fun-loving sing-along with a catchy melody line. Many artists, such as Gary Lewis and The Playboys and Nancy Sinatra, were quick to record cover versions. It was only later that, when analyzed, it dawned on authors, commentators and fans alike that Lennon was actually threatening to kill his lover.

Songwriting History

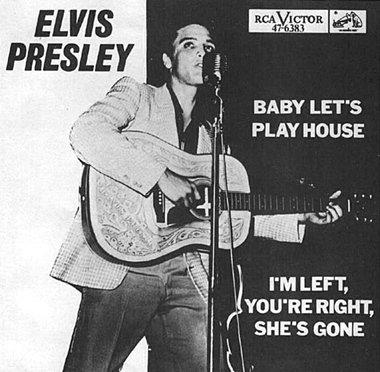

Although they swore off recording cover songs after the British “Help!” album was complete, a decision they stuck to throughout the rest of their recording career (except for the 30 second snippet of “Maggie Mae” on the “Let It Be” album), The Beatles still saw fit to pay tribute to their rock’n’roll roots in other ways. Concerning “Run For Your Life,” John explains: “It was inspired from ‘Baby, Let’s Play House.’ There was a line in it, I used to like specific lines from songs, ‘I’d rather see you dead, little girl, than to be with another man.’ I wrote it around that...a line from an old blues song that Presley did” Although they swore off recording cover songs after the British “Help!” album was complete, a decision they stuck to throughout the rest of their recording career (except for the 30 second snippet of “Maggie Mae” on the “Let It Be” album), The Beatles still saw fit to pay tribute to their rock’n’roll roots in other ways. Concerning “Run For Your Life,” John explains: “It was inspired from ‘Baby, Let’s Play House.’ There was a line in it, I used to like specific lines from songs, ‘I’d rather see you dead, little girl, than to be with another man.’ I wrote it around that...a line from an old blues song that Presley did”

“Baby, Let’s Play House” was the fourth single that Elvis Presley released on Sun Records in 1955. While it never became a national pop hit for the king, it was the first song he released that made a national chart, peaking at #5 on the Billboard Country Singles chart in July of 1955. Although Lennon referred to its origins as “an old blues song,” it actually only goes back a few months before Elvis recorded it on February 5th, 1955. The song was written by Arthur Gunter who recorded and released it himself on Excello Records in late 1954. It wasn’t successful enough to chart, but Elvis heard it and liked it enough to record it himself. “Baby, Let’s Play House” was the fourth single that Elvis Presley released on Sun Records in 1955. While it never became a national pop hit for the king, it was the first song he released that made a national chart, peaking at #5 on the Billboard Country Singles chart in July of 1955. Although Lennon referred to its origins as “an old blues song,” it actually only goes back a few months before Elvis recorded it on February 5th, 1955. The song was written by Arthur Gunter who recorded and released it himself on Excello Records in late 1954. It wasn’t successful enough to chart, but Elvis heard it and liked it enough to record it himself.

Paul’s book “Many Years From Now” says the song was written at John’s Kenwood home and “was largely John’s.” Since John described it as “just a song I knocked off,” it undoubtedly was written shortly before it was recorded. With their second US tour complete on August 31st, 1965, the group spent the next month-and-a-half writing new material for their next album which was to be released before the end of the year. This would put the writing of “Run For Your Life” within September and early October of 1965. Paul’s book “Many Years From Now” says the song was written at John’s Kenwood home and “was largely John’s.” Since John described it as “just a song I knocked off,” it undoubtedly was written shortly before it was recorded. With their second US tour complete on August 31st, 1965, the group spent the next month-and-a-half writing new material for their next album which was to be released before the end of the year. This would put the writing of “Run For Your Life” within September and early October of 1965.

While the intent of the lyric from “Baby, Let’s Play House” was to show the depth of the singer’s feelings for his girl, John decided to take that line literally as if it was a threat. The results are witty but chilling if read as poetry although, when sung against a country and western twang and three-part harmonies, it comes across as just another fun piece of Beatlemania. While the intent of the lyric from “Baby, Let’s Play House” was to show the depth of the singer’s feelings for his girl, John decided to take that line literally as if it was a threat. The results are witty but chilling if read as poetry although, when sung against a country and western twang and three-part harmonies, it comes across as just another fun piece of Beatlemania.

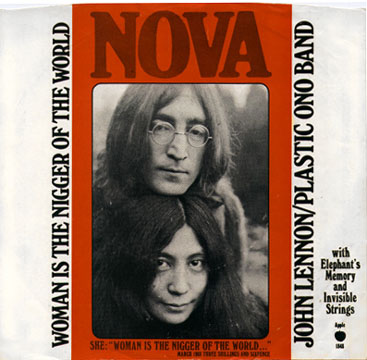

What is puzzling is that John always dismissed the song when asked about it. “Sort of a throwaway,” “I didn’t think it was that important,” “I never liked it,” “I always hated that one” and “it was phoney” were comments he made throughout the years. Since the lyrics could easily be viewed as sexist, his views on feminism in the seventies (evidenced in his song “Woman Is The N*gger Of The World”) may have tainted his view of the song "Run For Your Life" in retrospect. Nonetheless, Beatles fans worldwide do not share his negative view. In fact, many suggest it as one of the best on the album and as being a more-than-appropriate conclusion to “Rubber Soul.” What is puzzling is that John always dismissed the song when asked about it. “Sort of a throwaway,” “I didn’t think it was that important,” “I never liked it,” “I always hated that one” and “it was phoney” were comments he made throughout the years. Since the lyrics could easily be viewed as sexist, his views on feminism in the seventies (evidenced in his song “Woman Is The N*gger Of The World”) may have tainted his view of the song "Run For Your Life" in retrospect. Nonetheless, Beatles fans worldwide do not share his negative view. In fact, many suggest it as one of the best on the album and as being a more-than-appropriate conclusion to “Rubber Soul.”

Although Paul’s contribution as writer of the song is little if none, he does add a different spin on the meaning of the lyrics. “John was always on the run, running for his life,” McCartney stated. “He was married; whereas none of my songs would have “catch you with another man.” It was never a concern of mine, at all, because I had a girlfriend and I would go with other girls, it was a perfectly open relationship so I wasn’t as worried about that as John was. A bit of a macho song.” Although Paul’s contribution as writer of the song is little if none, he does add a different spin on the meaning of the lyrics. “John was always on the run, running for his life,” McCartney stated. “He was married; whereas none of my songs would have “catch you with another man.” It was never a concern of mine, at all, because I had a girlfriend and I would go with other girls, it was a perfectly open relationship so I wasn’t as worried about that as John was. A bit of a macho song.”

Another interesting comment that John made about “Run For Your Life” to Playboy Magazine in 1980 was that “it was a favor to George.” Although this wasn’t explained any further, George Harrison definitely played a big role in recording the song, playing no less than four guitar parts. The song may have deliberately been written in a style that suited George’s guitar playing and therefore warranted mention by John many years later. It was no wonder that, in 1970, John commented that the song "was always a favorite of George's." Another interesting comment that John made about “Run For Your Life” to Playboy Magazine in 1980 was that “it was a favor to George.” Although this wasn’t explained any further, George Harrison definitely played a big role in recording the song, playing no less than four guitar parts. The song may have deliberately been written in a style that suited George’s guitar playing and therefore warranted mention by John many years later. It was no wonder that, in 1970, John commented that the song "was always a favorite of George's."

Recording History

With the pressure of time constraints to record a new album by the end of the year, The Beatles entered EMI Studio Two on October 12th, 1965 for what was to be the first recording session for “Rubber Soul.” This four-and-a-half hour recording session, running from 2:30 to 7 pm, was devoted entirely to recording the new composition “Run For Your Life.” This session was all that was needed to complete the song in its entirety, overdubs and all. Another new song, “Norwegian Wood,” was also ready to record, but that began to be taped immediately afterward on the second session of the day. With the pressure of time constraints to record a new album by the end of the year, The Beatles entered EMI Studio Two on October 12th, 1965 for what was to be the first recording session for “Rubber Soul.” This four-and-a-half hour recording session, running from 2:30 to 7 pm, was devoted entirely to recording the new composition “Run For Your Life.” This session was all that was needed to complete the song in its entirety, overdubs and all. Another new song, “Norwegian Wood,” was also ready to record, but that began to be taped immediately afterward on the second session of the day.

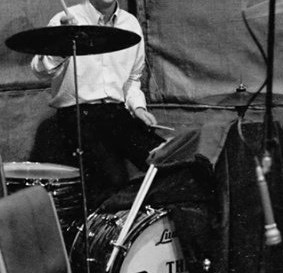

The rhythm track was the first to be tackled, which comprised John on acoustic guitar and guide vocals, Paul on bass, George on electric rhythm guitar and Ringo on his brand new set of Ludwig drums. They tried five takes of the rhythm track, although "take five" was the only one that made it all the way through to the end, the first four all breaking down at some point. The rhythm track was the first to be tackled, which comprised John on acoustic guitar and guide vocals, Paul on bass, George on electric rhythm guitar and Ringo on his brand new set of Ludwig drums. They tried five takes of the rhythm track, although "take five" was the only one that made it all the way through to the end, the first four all breaking down at some point.

John’s vocal on the rhythm track was performed with much bravado and enthusiasm, possibly with the intention of it being used in the finished product. It was even recorded with a reverb effect to give it some depth. However, possibly because he repeated the second verse where the third verse should have been, this was later scrapped in favor of a new overdubbed vocal. Luckily, the guide vocal was recorded on a separate track so it could be mixed out or recorded over with little or no bleed-through on the rhythm track.

Although, as previously noted, John Lennon was later very insistent about his dislike for the song, this guide vocal reveals that he was very much into the spirit of the recording and was wholehearted about his performance. The same can be said about his overdubbed vocals on the finished master tape. Obviously, his distaste for the song came later. Although, as previously noted, John Lennon was later very insistent about his dislike for the song, this guide vocal reveals that he was very much into the spirit of the recording and was wholehearted about his performance. The same can be said about his overdubbed vocals on the finished master tape. Obviously, his distaste for the song came later.

Onto "take five," they immediately began the overdubbing process. With the guide vocals still in place, Ringo laid down a tambourine part and George got busy laying down multiple lead guitar passages, including the solo. His other parts included the distinctive riff heard in the introduction as well as throughout the song, these all being double-tracked to make them sound full. He also overdubbed chord "slides" that are accomplished by pulling the chord position on his left hand up into D major as heard repeatedly throughout the song. During strategic places, there are actually four Georges being heard at the same time! Onto "take five," they immediately began the overdubbing process. With the guide vocals still in place, Ringo laid down a tambourine part and George got busy laying down multiple lead guitar passages, including the solo. His other parts included the distinctive riff heard in the introduction as well as throughout the song, these all being double-tracked to make them sound full. He also overdubbed chord "slides" that are accomplished by pulling the chord position on his left hand up into D major as heard repeatedly throughout the song. During strategic places, there are actually four Georges being heard at the same time!

At some point during this overdubbing process, John voiced a slight complaint. “You know, as soon as the backing came in the rhythm went all soft,” he informed the EMI staff. His concern was that the overdubs were going to be mixed louder than the original rhythm track. He continued, “By the time we put something else on there’ll be no ‘Jumbo’ Gibson at all,” referring to his acoustic guitar as played on the rhythm track. At some point during this overdubbing process, John voiced a slight complaint. “You know, as soon as the backing came in the rhythm went all soft,” he informed the EMI staff. His concern was that the overdubs were going to be mixed louder than the original rhythm track. He continued, “By the time we put something else on there’ll be no ‘Jumbo’ Gibson at all,” referring to his acoustic guitar as played on the rhythm track.

With that settled, John’s lead vocal track, as well as Paul and George’s higher harmony vocals on the choruses, were added. The three of them then double-tracked their vocals but only during the choruses, strategically omitting the final “little girl” as heard at the end of each chorus. After this was done, the song was complete.

The first date that any mixes were done for the “Rubber Soul” album was October 25th, 1965, nearly two weeks after the completion of “Run For Your Life.” Curiously, this song did not get mixed at this time. Six other completed songs did received a mono mix on this day and other songs that were recorded but not considered complete at this point were understandably left for later. Why wouldn’t they create a mix for “Run For Your Life” at this point? Could they have viewed the song as incomplete as well? Or was it just forgotten at this stage? The first date that any mixes were done for the “Rubber Soul” album was October 25th, 1965, nearly two weeks after the completion of “Run For Your Life.” Curiously, this song did not get mixed at this time. Six other completed songs did received a mono mix on this day and other songs that were recorded but not considered complete at this point were understandably left for later. Why wouldn’t they create a mix for “Run For Your Life” at this point? Could they have viewed the song as incomplete as well? Or was it just forgotten at this stage?

Either way, they did include it in the mono mixing session held on November 9th, 1965 in Room 65 at EMI Studios. The song got its official mono mix at this time, which was created by George Martin and engineers Norman Smith and Jerry Boys. Interestingly, as a surviving acetate pressing shows, "Run For Your Life" was originally slated as the closing track of side one on the British "Rubber Soul" album after "Michelle," a decision being made shortly after to have the song close out side two instead. Either way, they did include it in the mono mixing session held on November 9th, 1965 in Room 65 at EMI Studios. The song got its official mono mix at this time, which was created by George Martin and engineers Norman Smith and Jerry Boys. Interestingly, as a surviving acetate pressing shows, "Run For Your Life" was originally slated as the closing track of side one on the British "Rubber Soul" album after "Michelle," a decision being made shortly after to have the song close out side two instead.

The stereo mix of "Run For Your Life" was made the next day, November 10th, 1965, also in Room 65 at EMI Studios by the same engineering team. The entire rhythm track was isolated in the left channel as was the tambourine overdub, the second set of harmonized vocals in the chorus, and one of George's overdubbed guitar riff tracks. The lead vocal track, which included the first set of harmonized vocals from Paul and George, are isolated in the right track, as are George’s "slide" chords, the other guitar riff track, and the guitar solo. Separating the guitar riffs in separate channels adds a very effective fullness to the finished recording. The stereo mix of "Run For Your Life" was made the next day, November 10th, 1965, also in Room 65 at EMI Studios by the same engineering team. The entire rhythm track was isolated in the left channel as was the tambourine overdub, the second set of harmonized vocals in the chorus, and one of George's overdubbed guitar riff tracks. The lead vocal track, which included the first set of harmonized vocals from Paul and George, are isolated in the right track, as are George’s "slide" chords, the other guitar riff track, and the guitar solo. Separating the guitar riffs in separate channels adds a very effective fullness to the finished recording.

A few anomalies in this mix include a loud popping sound heard during the eighth measure of the guitar solo, possibly from someone accidentally hitting a microphone or guitar pick-up. The second curiosity is that, during the introduction, all of George’s guitar overdubs are heard only in the left channel, while some of these elements are heard in the right channel for the rest of the song. This being the case, the first four measures of the song are heard entirely in the left channel of the stereo mix, while on the fifth measure we hear a little of the rhythm track, overdubs and all, fade up in the right channel just before John’s vocals begin. This occurred because of the instrumental backing being played in the studio and it being picked up by John’s vocal microphone during that overdub session. A few anomalies in this mix include a loud popping sound heard during the eighth measure of the guitar solo, possibly from someone accidentally hitting a microphone or guitar pick-up. The second curiosity is that, during the introduction, all of George’s guitar overdubs are heard only in the left channel, while some of these elements are heard in the right channel for the rest of the song. This being the case, the first four measures of the song are heard entirely in the left channel of the stereo mix, while on the fifth measure we hear a little of the rhythm track, overdubs and all, fade up in the right channel just before John’s vocals begin. This occurred because of the instrumental backing being played in the studio and it being picked up by John’s vocal microphone during that overdub session.

A second stereo mix was made by George Martin in 1986 in preparation for the compact disc release of “Rubber Soul” in 1987. The elements were essentially placed in the exact same locations with the exception of the lead vocals which were panned slightly more toward the center. George Martin took the opportunity at this point to fix the loud popping sound in the guitar solo, which may have been originally present due to an unused track being up in the original mix. A second stereo mix was made by George Martin in 1986 in preparation for the compact disc release of “Rubber Soul” in 1987. The elements were essentially placed in the exact same locations with the exception of the lead vocals which were panned slightly more toward the center. George Martin took the opportunity at this point to fix the loud popping sound in the guitar solo, which may have been originally present due to an unused track being up in the original mix.

There were a couple more recordings made of the song late in The Beatles career. On January 21st, 1969, during the “Get Back / Let It Be” sessions at Apple Studios on Savile Row in London, an impromptu 30 second run-through of “Run For Your Life” occurred and was captured on tape. John started singing the first verse while playing acoustic guitar, being joined by the rest of The Beatles with Paul singing harmony. It obviously didn’t make it onto the resulting album, but it adorns bootlegs to this day. Something similar occured again at Apple Studios on January 31st of that year, this rendition appearing in the 2021 Peter Jackson "Get Back" series. There were a couple more recordings made of the song late in The Beatles career. On January 21st, 1969, during the “Get Back / Let It Be” sessions at Apple Studios on Savile Row in London, an impromptu 30 second run-through of “Run For Your Life” occurred and was captured on tape. John started singing the first verse while playing acoustic guitar, being joined by the rest of The Beatles with Paul singing harmony. It obviously didn’t make it onto the resulting album, but it adorns bootlegs to this day. Something similar occured again at Apple Studios on January 31st of that year, this rendition appearing in the 2021 Peter Jackson "Get Back" series.

Song Structure and Style

Here is yet another example of The Beatles use of a chorus, “Rubber Soul” utilizing this element more than any other of their albums up to this point. The structure contained in “Run For Your Life” consists of ‘verse/ chorus/ verse/ chorus/ instrumental/ verse/ chorus/ verse/ chorus’ (or ababcabab). The format also includes a brief introduction and a similar but fading conclusion. Here is yet another example of The Beatles use of a chorus, “Rubber Soul” utilizing this element more than any other of their albums up to this point. The structure contained in “Run For Your Life” consists of ‘verse/ chorus/ verse/ chorus/ instrumental/ verse/ chorus/ verse/ chorus’ (or ababcabab). The format also includes a brief introduction and a similar but fading conclusion.

A six-measure introduction is heard first, which starts off with a two-measure acoustic guitar intro from John in the folksy rhythmic style that we’ll hear throughout the entire song. He actually starts playing just before the downbeat, but when the rest of the band kicks in at the beginning of the third measure, we then know for sure where the true one-beat is located. The entire introduction stays planted in the home key of D major while George premiers the catchy guitar riff that will continue to be used as a transition between the chorus and following verse in most instances throughout the song.

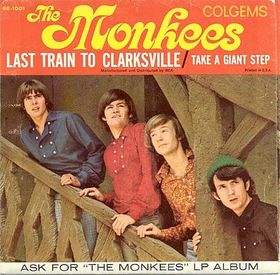

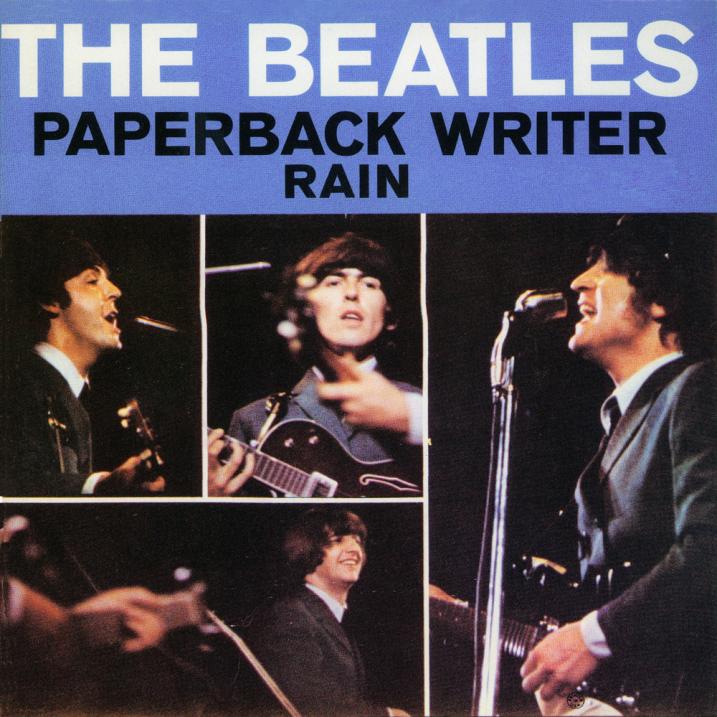

This guitar riff takes on the familiar two-measure repeating form that The Beatles utilized many times previously and will again in the later years. While it may not be as inventive as that heard in “You Can’t Do That” and “I Feel Fine” from the previous year, nor as identifiable as “Day Tripper” and “Paperback Writer” which it preceded, it still works nicely as a foundation to build the song upon. Its descending structure may very well have been a template for Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart to work into “Last Train To Clarksville” the following year, since The Beatles’ influence on that song has already been verified to come from “Paperback Writer.” This guitar riff takes on the familiar two-measure repeating form that The Beatles utilized many times previously and will again in the later years. While it may not be as inventive as that heard in “You Can’t Do That” and “I Feel Fine” from the previous year, nor as identifiable as “Day Tripper” and “Paperback Writer” which it preceded, it still works nicely as a foundation to build the song upon. Its descending structure may very well have been a template for Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart to work into “Last Train To Clarksville” the following year, since The Beatles’ influence on that song has already been verified to come from “Paperback Writer.”

The remainder of the instrumentation, this consisting of bass guitar, drums, tambourine and lead guitars, all appear simultaneously in the third measure of the introduction. With the exception of the recurring lead guitar parts, they all continue in full force throughout the entire song without a break. The remainder of the instrumentation, this consisting of bass guitar, drums, tambourine and lead guitars, all appear simultaneously in the third measure of the introduction. With the exception of the recurring lead guitar parts, they all continue in full force throughout the entire song without a break.

The first eight-measure verse then begins with John’s single-tracked vocals coming in slightly before the downbeat with the words “Well, I’d / rather see you dead…” All three of George’s lead guitar overdubs disappear from sight during the verse, as with all of the verses, although his rhythm playing from the rhythm track is very prominent. Also noteworthy is John flubbing the lyrics at the end of the sixth measure, singing “you better keep your head, little girl, or I won’t know where I am” instead of “or you won’t know” which makes more sense. He sings the lyrics correctly when the verse is repeated later.

The eight-measure chorus is heard next, which surprisingly begins with the last chord of the verse, changing the key to B minor at this point instead of D major as heard from the song’s beginning. John’s vocals are now double-tracked as are the background vocals from Paul and George which occur for the first time at the beginning of this chorus. These background vocals follow John’s emphasis to the tee, especially evident in the seventh measure on the line “that’s the end-ah.” The lead guitar is still nowhere to be found except for the eighth measure (just after the delayed lyrics “little girl”) when it begins a climb to segue into a four-measure version of the introduction which immediately follows the chorus. This repeat of the introduction returns us to sure footing by bringing back the home key of D major. The catchy-but-familiar guitar riff is then repeated, double-tracking spanned between both channels this time around. The eight-measure chorus is heard next, which surprisingly begins with the last chord of the verse, changing the key to B minor at this point instead of D major as heard from the song’s beginning. John’s vocals are now double-tracked as are the background vocals from Paul and George which occur for the first time at the beginning of this chorus. These background vocals follow John’s emphasis to the tee, especially evident in the seventh measure on the line “that’s the end-ah.” The lead guitar is still nowhere to be found except for the eighth measure (just after the delayed lyrics “little girl”) when it begins a climb to segue into a four-measure version of the introduction which immediately follows the chorus. This repeat of the introduction returns us to sure footing by bringing back the home key of D major. The catchy-but-familiar guitar riff is then repeated, double-tracking spanned between both channels this time around.

A second verse and chorus then occurs which repeats the same instrumentation with the exception of the omission of the climbing lead guitar in the final measure of the chorus. Instead of moving into another repeat of the introduction, we’re brought back to the home key of D major for an instrumental break. This appears in a full nearly-standard twelve-bar-blues format, the only time it’s heard in the entire song. The only thing that isn’t ‘standard’ is the tenth measure where they stay on the A major chord instead of moving back to G as expected. A second verse and chorus then occurs which repeats the same instrumentation with the exception of the omission of the climbing lead guitar in the final measure of the chorus. Instead of moving into another repeat of the introduction, we’re brought back to the home key of D major for an instrumental break. This appears in a full nearly-standard twelve-bar-blues format, the only time it’s heard in the entire song. The only thing that isn’t ‘standard’ is the tenth measure where they stay on the A major chord instead of moving back to G as expected.

A third verse follows immediately afterward which features Lennon’s single-tracked and slightly menacing vocal delivery, especially the emphasized final line “I’d rather see you dead-ah.” An identical repeat of the chorus follows with another occurrence of the introduction coming immediately afterward. Then the first verse is repeated, John this time getting the words right. The fourth and final chorus is then heard with a stray lead guitar note from George appearing in the eighth measure. A third verse follows immediately afterward which features Lennon’s single-tracked and slightly menacing vocal delivery, especially the emphasized final line “I’d rather see you dead-ah.” An identical repeat of the chorus follows with another occurrence of the introduction coming immediately afterward. Then the first verse is repeated, John this time getting the words right. The fourth and final chorus is then heard with a stray lead guitar note from George appearing in the eighth measure.

The introduction now becomes the conclusion and fade-out of the song as the descending guitar riff repeats endlessly while John emphasizes the end of the song with his “nah, nah, nah” scat vocal lines. With this, the song “Run For Your Life,” as well as the “Rubber Soul” album experience, comes to a fitting conclusion. The introduction now becomes the conclusion and fade-out of the song as the descending guitar riff repeats endlessly while John emphasizes the end of the song with his “nah, nah, nah” scat vocal lines. With this, the song “Run For Your Life,” as well as the “Rubber Soul” album experience, comes to a fitting conclusion.

From listening to the song there is no doubt in anyone’s mind that John Lennon is truly at the helm; he is definitely steering this ship. Playing the role of folk singer/songwriter, acoustic guitar in hand, he has a definite and clear message to convey and commands our attention with his deliberate and intentional vocal delivery. Paul plays a supporting character through echoing and accentuating John’s thoughts in harmony as well as with his tasteful bass work. Ringo, while barely noticed on the drum kit, makes his presence felt through his relentless tambourine which is much higher in the mix. From listening to the song there is no doubt in anyone’s mind that John Lennon is truly at the helm; he is definitely steering this ship. Playing the role of folk singer/songwriter, acoustic guitar in hand, he has a definite and clear message to convey and commands our attention with his deliberate and intentional vocal delivery. Paul plays a supporting character through echoing and accentuating John’s thoughts in harmony as well as with his tasteful bass work. Ringo, while barely noticed on the drum kit, makes his presence felt through his relentless tambourine which is much higher in the mix.

George is instrumentally the major player in the song, sounding as if he is in his comfort zone from beginning to end. While his input in some “Rubber Soul” songs appears to be minor (such as in “In My Life” and “I’m Looking Through You”), his presence is definitely felt here, adding three guitar overdubs as well as an excellently executed guitar solo. George is instrumentally the major player in the song, sounding as if he is in his comfort zone from beginning to end. While his input in some “Rubber Soul” songs appears to be minor (such as in “In My Life” and “I’m Looking Through You”), his presence is definitely felt here, adding three guitar overdubs as well as an excellently executed guitar solo.

As stated earlier, John is now writing lyrics without any pretense of keeping within an established pop mentality. If he wants to write autobiographically (“In My Life”), he does. If he wants to write about an affair (“Norwegian Wood”), he does. If he wants to sing about his revelations reached during drug use (“The Word”), he does. And, if he wants to write about his murderous and jealous rage, no one, not even Brian Epstein, can tell him at this point that he can’t. As stated earlier, John is now writing lyrics without any pretense of keeping within an established pop mentality. If he wants to write autobiographically (“In My Life”), he does. If he wants to write about an affair (“Norwegian Wood”), he does. If he wants to sing about his revelations reached during drug use (“The Word”), he does. And, if he wants to write about his murderous and jealous rage, no one, not even Brian Epstein, can tell him at this point that he can’t.

This may have been the reason why Norman Smith, who had been their primary engineer up to this point, decided to abandon The Beatles project after these sessions were complete. “’Rubber Soul’ wasn’t really my bag at all,” he was quoted as saying, “so I decided that I’d better get off The Beatles’ train. I told George (Martin) and George told Eppy (Brian Epstein) and the next thing I received a lovely gold carriage clock inscribed ‘To Norman. Thanks. John, Paul, George and Ringo.’” This may have been the reason why Norman Smith, who had been their primary engineer up to this point, decided to abandon The Beatles project after these sessions were complete. “’Rubber Soul’ wasn’t really my bag at all,” he was quoted as saying, “so I decided that I’d better get off The Beatles’ train. I told George (Martin) and George told Eppy (Brian Epstein) and the next thing I received a lovely gold carriage clock inscribed ‘To Norman. Thanks. John, Paul, George and Ringo.’”

While admitting that he is “a wicked guy” with “a jealous mind,” John justifies his irrational intent by saying that he’s not going to spend his “whole life” trying to get her to “toe the line.” Taking the Arthur Gunter line “I’d rather see you dead” to a literal degree, he warns her to “run for your life” and “hide your head in the sand” saying “that’s the end” for her if she is unfaithful. To show he’s not kidding one iota, he reiterates that the lyrics to this song are to be as his “sermon” to her, emphasizing that he’s “determined” to see her “dead.” While admitting that he is “a wicked guy” with “a jealous mind,” John justifies his irrational intent by saying that he’s not going to spend his “whole life” trying to get her to “toe the line.” Taking the Arthur Gunter line “I’d rather see you dead” to a literal degree, he warns her to “run for your life” and “hide your head in the sand” saying “that’s the end” for her if she is unfaithful. To show he’s not kidding one iota, he reiterates that the lyrics to this song are to be as his “sermon” to her, emphasizing that he’s “determined” to see her “dead.”

The seriousness of the lyrical content is diluted, however, by a silly play-on-words in the first and final verse. “You better keep your head, little girl, or you won’t know where I am,” he playfully repeats. After all, if she doesn’t have a literal head, she wouldn’t be able to see where he is.

American Releases

America got to enjoy the song immediately after Britain did as Capitol included it as the final track to the American version of “Rubber Soul,” which was released on December 6th, 1965. Because of this exposure, the Beatles Cartoon series made sure to include it extensively in animated features despite having homicidal lyrics. This US version of "Rubber Soul" was released on an individual compact disc on January 21, 2014, both the mono and stereo versions of the album being contained on a single CD. America got to enjoy the song immediately after Britain did as Capitol included it as the final track to the American version of “Rubber Soul,” which was released on December 6th, 1965. Because of this exposure, the Beatles Cartoon series made sure to include it extensively in animated features despite having homicidal lyrics. This US version of "Rubber Soul" was released on an individual compact disc on January 21, 2014, both the mono and stereo versions of the album being contained on a single CD.

Sometime in 1967, Capitol released Beatles music on a brand new but short-lived format called "Playtapes." These tape cartridges did not have the capability to include entire albums, so two truncated four-song versions of "Rubber Soul" were released in this portable format, "Run For Your Life" being on one of them. These "Playtapes" are highly collectable today. Sometime in 1967, Capitol released Beatles music on a brand new but short-lived format called "Playtapes." These tape cartridges did not have the capability to include entire albums, so two truncated four-song versions of "Rubber Soul" were released in this portable format, "Run For Your Life" being on one of them. These "Playtapes" are highly collectable today.

The first time the original British "Rubber Soul” album was made available in the US was the "Original Master Recording" vinyl edition released through Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab in June of 1984. This album included "Run For Your Life" and was prepared utilizing half-speed mastering technology from the original master tape on loan from EMI. This version of the album was only available for a short time and is quite collectible today. The first time the original British "Rubber Soul” album was made available in the US was the "Original Master Recording" vinyl edition released through Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab in June of 1984. This album included "Run For Your Life" and was prepared utilizing half-speed mastering technology from the original master tape on loan from EMI. This version of the album was only available for a short time and is quite collectible today.

On April 30th, 1987, the first compact disc version of “Rubber Soul” was released, which included the 1986 George Martin stereo mix of “Run For Your Life.” This fourteen-track version of the album was also released on vinyl on July 21st, 1987. This new George Martin mix was also used when the CD was remastered and re-released on September 9th, 2009, a remastered vinyl edition coming out on November 13th, 2012. Extensive measures were taken on this remastered version to remove the popping on John Lennon’s vocal track, such as when he sang “to be with another man…you better keep your head…” for instance. On April 30th, 1987, the first compact disc version of “Rubber Soul” was released, which included the 1986 George Martin stereo mix of “Run For Your Life.” This fourteen-track version of the album was also released on vinyl on July 21st, 1987. This new George Martin mix was also used when the CD was remastered and re-released on September 9th, 2009, a remastered vinyl edition coming out on November 13th, 2012. Extensive measures were taken on this remastered version to remove the popping on John Lennon’s vocal track, such as when he sang “to be with another man…you better keep your head…” for instance.

November 16th, 2004 was the next release date for the song on the box set “The Capitol Albums, Vol. 2.” Since the original 1965 stereo and mono mixes were used on this release, this is the only CD available that contains the loud popping sound in the eighth measure of the guitar solo, if it happens to be important for you to hear that on compact disc. For initial pressings of this set, Capitol mistakenly presented a "mono type-B" fold-down mono mix of the entire "Rubber Soul" album, which was a method of combining both the left and right channels of the stereo mix to create a mono mix. Therefore, the mono mix of "Run For Your Life" in this set was initially prepared in this way, the error being corrected on subsequent pressings. November 16th, 2004 was the next release date for the song on the box set “The Capitol Albums, Vol. 2.” Since the original 1965 stereo and mono mixes were used on this release, this is the only CD available that contains the loud popping sound in the eighth measure of the guitar solo, if it happens to be important for you to hear that on compact disc. For initial pressings of this set, Capitol mistakenly presented a "mono type-B" fold-down mono mix of the entire "Rubber Soul" album, which was a method of combining both the left and right channels of the stereo mix to create a mono mix. Therefore, the mono mix of "Run For Your Life" in this set was initially prepared in this way, the error being corrected on subsequent pressings.

September 9th, 2009 is also the date that the CD box set “The Beatles In Mono” was released, which also features the original 1965 mono and stereo mixes, although they have been cleaned up. The vinyl edition of this box set was first released on September 9th, 2014.

Live Performances

For those who are interested in fantasizing what it would have been like to hear The Beatles perform “Run For Your Life” live, check out “The Beatles: Rock Band.” They feature an animated Beatles rendition of the song from Shea Stadium. Otherwise, The Beatles never performed it live. For those who are interested in fantasizing what it would have been like to hear The Beatles perform “Run For Your Life” live, check out “The Beatles: Rock Band.” They feature an animated Beatles rendition of the song from Shea Stadium. Otherwise, The Beatles never performed it live.

Conclusion

With “Run For Your Life,” a new trend within The Beatles recording sessions began. “John could talk over most anyone if he wanted to,” states Geoff Emerick in his book “Here There and Everywhere,” continuing, “and he was never shy about jumping the queue; in fact, the first session for almost every Beatles album was devoted to recording one of his songs.” With “Run For Your Life,” a new trend within The Beatles recording sessions began. “John could talk over most anyone if he wanted to,” states Geoff Emerick in his book “Here There and Everywhere,” continuing, “and he was never shy about jumping the queue; in fact, the first session for almost every Beatles album was devoted to recording one of his songs.”

From this point forward, whenever they entered into the recording studio with the intention of recording another album, with the exception of “Magical Mystery Tour” (which wasn’t initially an album anyway), John Lennon asserted himself to record one of his songs first. This does seem to give evidence that he must have felt strongly about the song initially, even though he was eager to dismiss it as “a throwaway” in later years. In my humble opinion, as I’m sure most others would agree, “Run For Your Life” is hardly a throwaway track. Instead, it ends the groundbreaking “Rubber Soul” album in a fun yet biting way. Certainly from this point on, you just couldn’t predict what would be coming out of John Lennon’s compositional pen. From this point forward, whenever they entered into the recording studio with the intention of recording another album, with the exception of “Magical Mystery Tour” (which wasn’t initially an album anyway), John Lennon asserted himself to record one of his songs first. This does seem to give evidence that he must have felt strongly about the song initially, even though he was eager to dismiss it as “a throwaway” in later years. In my humble opinion, as I’m sure most others would agree, “Run For Your Life” is hardly a throwaway track. Instead, it ends the groundbreaking “Rubber Soul” album in a fun yet biting way. Certainly from this point on, you just couldn’t predict what would be coming out of John Lennon’s compositional pen.

Song Summary

“Run For Your Life”

Written by: John Lennon / Paul McCartney

-

Song Written: September/October, 1965

-

Song Recorded: October 12, 1965

-

First US Release Date: December 6, 1965

-

-

US Single Release: n/a

-

Highest Chart Position: n/a

-

British Album Release: Parlophone #PCS 3075 “Rubber Soul”

-

Length: 2:21

-

Producer: George Martin

-

Engineers: Norman Smith, Ken Scott, Phil McDonald

Instrumentation (most likely):

-

John Lennon - Lead Vocals, Rhythm Guitar (1964 Gibson J160E)

-

George Harrison – Lead and Rhythm Guitar (1963 Gretsch 6119 Tennessean and 1961 Sonic Blue Fender Stratocaster), Harmony Vocals

-

Paul McCartney - Bass Guitar (1963 Hofner 500/1), Harmony Vocals

-

Ringo Starr – Drums (1965 Ludwig Super Classic Black Oyster Pearl), tambourine

Written and compiled by Dave Rybaczewski

|

IF YOU WOULD LIKE TO MAKE A DONATION TO KEEP THIS WEBSITE UP AND RUNNING, PLEASE CLICK BELOW!

|