Search by Keyword

Sign Up Below for our MONTHLY BEATLES TRIVIA QUIZ!

|

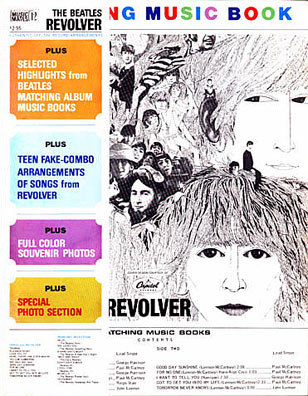

“TOMORROW NEVER KNOWS”

(John Lennon – Paul McCartney)

A deserved five month break from the studio for a popular recording group is usually a refreshing experience used to reassess their artistic direction. An example that is a little more recent is Coldplay, who have habitually taken huge amounts of time away from the studio and have released albums with three year gaps in between. This has actually become a quite standard practice as time has progressed. For the music industry of the '60s, however, five months was an eternity. The "powers that be" surrounding The Beatles made sure they knew that. A deserved five month break from the studio for a popular recording group is usually a refreshing experience used to reassess their artistic direction. An example that is a little more recent is Coldplay, who have habitually taken huge amounts of time away from the studio and have released albums with three year gaps in between. This has actually become a quite standard practice as time has progressed. For the music industry of the '60s, however, five months was an eternity. The "powers that be" surrounding The Beatles made sure they knew that.

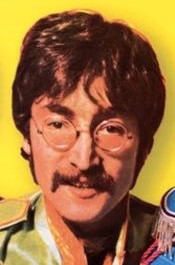

The thirteen hour marathon session of November 11th, 1965 yielded two amazingly melodic pop standards and the finishing touches to two others, all of which graced the masterpiece album “Rubber Soul.” John Lennon’s main contribution on this day, this being the beautiful song “Girl,” exhibited a lyrical maturity that appeared to pave the way for many further innovations from its composer. Lennon's creativity at this point was admittedly being fueled by his frequent use of softer drugs such as marijuana, but John's obsession with LSD in 1966 was to change his songwriting output drastically. The thirteen hour marathon session of November 11th, 1965 yielded two amazingly melodic pop standards and the finishing touches to two others, all of which graced the masterpiece album “Rubber Soul.” John Lennon’s main contribution on this day, this being the beautiful song “Girl,” exhibited a lyrical maturity that appeared to pave the way for many further innovations from its composer. Lennon's creativity at this point was admittedly being fueled by his frequent use of softer drugs such as marijuana, but John's obsession with LSD in 1966 was to change his songwriting output drastically.

I can’t imagine anyone accurately predicting what came next from the pen of Mr. Lennon nearly five months later. It seems that even his fellow band-mates were equally flabbergasted, but they were eager to blaze this new trail. Probably never before in pop music history could a five month break result in such an imaginative new direction as did the unveiling of “Tomorrow Never Knows.” I can’t imagine anyone accurately predicting what came next from the pen of Mr. Lennon nearly five months later. It seems that even his fellow band-mates were equally flabbergasted, but they were eager to blaze this new trail. Probably never before in pop music history could a five month break result in such an imaginative new direction as did the unveiling of “Tomorrow Never Knows.”

Songwriting History

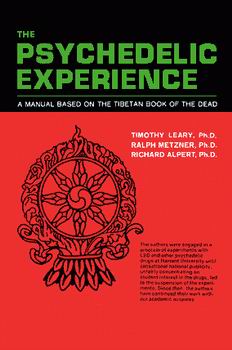

The inspiration for the song came from a book called “The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based On The Tibetan Book Of The Dead.” This book was published in August of 1964 by Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner and Richard Alpert (also known as Ram Dass, author of the classic 1971 book “Be Here Now”). The inspiration for the song came from a book called “The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based On The Tibetan Book Of The Dead.” This book was published in August of 1964 by Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner and Richard Alpert (also known as Ram Dass, author of the classic 1971 book “Be Here Now”).

In his 1994 book "A Hard Day's Write," author Steve Turner explains that Timothy Leary “had spent seven months in the Himalayas studying Tibetan Buddhism under Lama Govinda. (The book) was a direct result of this period of study.” Leary himself explains: “’Book Of The Dead’ really means ‘Book Of The Dying’ but it’s your ego rather than your body which is dying. The book is a classic. It’s the Bible of Tibetan Buddhism. The concept of Buddhism is of the void and of reaching the void.” Timothy Leary admittedly intended his book "The Psychedelic Experience" to be enjoyed along with experiencing psychedelic drugs (the final chapter entitled “Instructions For Use During a Psychedelic Session” being a dead giveaway) which were then starting to become quite popular.

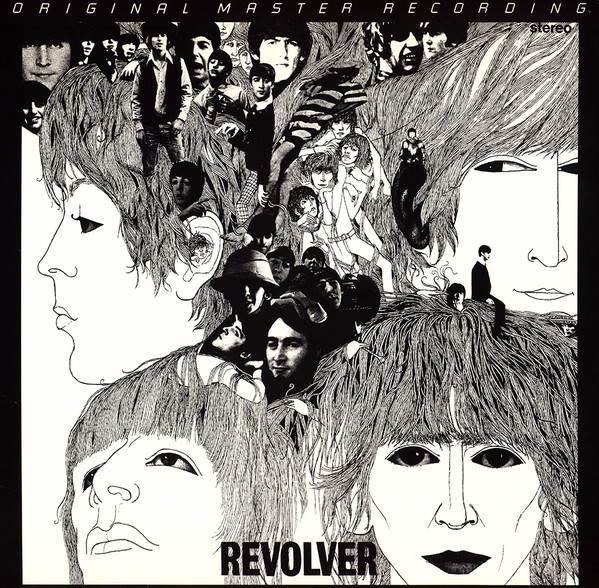

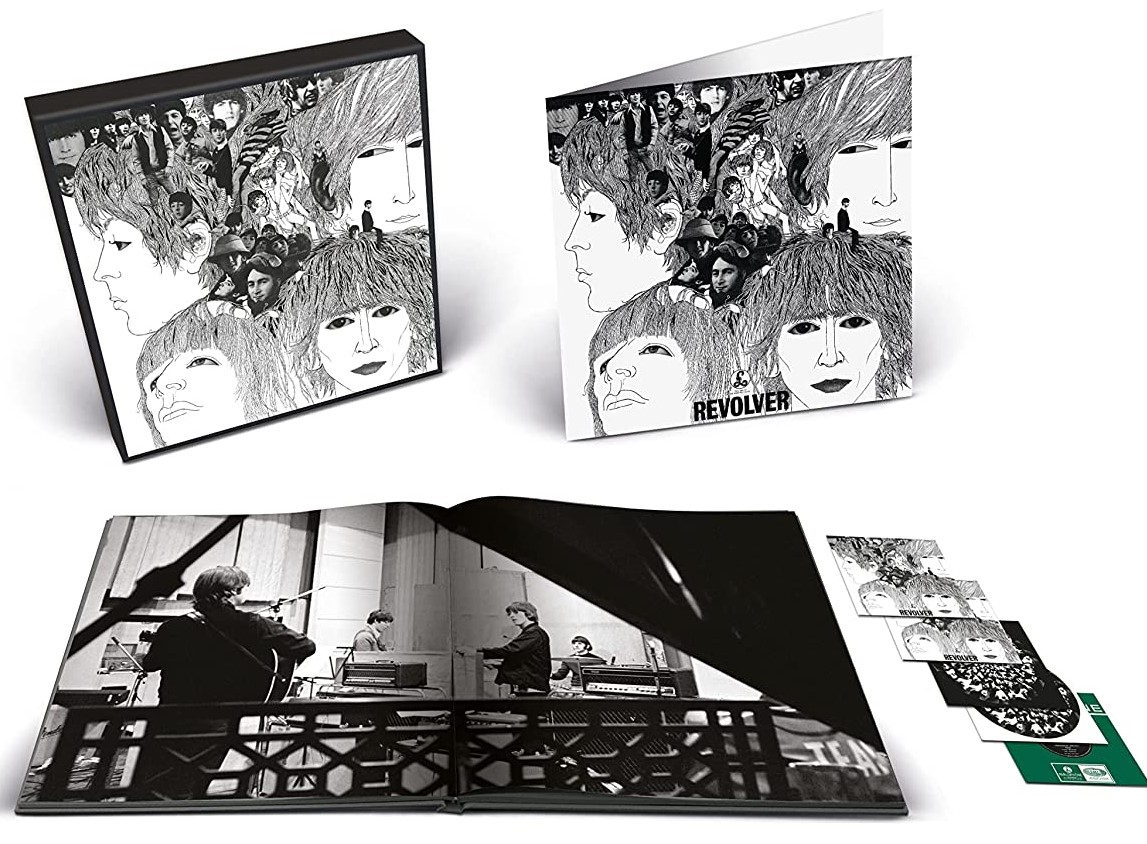

Barry Miles, who was a close friend of The Beatles, ran Indica Books in London and, as requested by the group, sent them significant pieces of literature concerning the counter-culture when he obtained them. As detailed by Kevin Howlett in the 2022 "Revolver" Deluxe editions, "Barry Miles, the co-owner of Indica, remembered John visiting with Paul in search of something by German philosopher Fredrich Nietsche. Having handed him 'The Portable Nietsche,' Miles showed John a book that had just arrived - 'The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based On The Tibetan Book Of The Dead.'...'John was delighted,' Miles remembered, 'and curled up with the book on the old settee we had in the middle of the shop.'" Barry Miles, who was a close friend of The Beatles, ran Indica Books in London and, as requested by the group, sent them significant pieces of literature concerning the counter-culture when he obtained them. As detailed by Kevin Howlett in the 2022 "Revolver" Deluxe editions, "Barry Miles, the co-owner of Indica, remembered John visiting with Paul in search of something by German philosopher Fredrich Nietsche. Having handed him 'The Portable Nietsche,' Miles showed John a book that had just arrived - 'The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based On The Tibetan Book Of The Dead.'...'John was delighted,' Miles remembered, 'and curled up with the book on the old settee we had in the middle of the shop.'"

The actual "Tibetan Book Of The Dead" was a 1927 translation of an ancient Buddhist text entitled "Bardo Thodol." For those who were newly enamored with LSD in the '60s as John was, a thirst for deeper meaning was desired in order to make sense of, or try to explain, the sensory images and unpredictable effects that were commonly experienced when taking the drug, which was legal in 1966. This is where Timothy Leary's interpretation of the "Tibetan Book Of The Dead" came in handy. The actual "Tibetan Book Of The Dead" was a 1927 translation of an ancient Buddhist text entitled "Bardo Thodol." For those who were newly enamored with LSD in the '60s as John was, a thirst for deeper meaning was desired in order to make sense of, or try to explain, the sensory images and unpredictable effects that were commonly experienced when taking the drug, which was legal in 1966. This is where Timothy Leary's interpretation of the "Tibetan Book Of The Dead" came in handy.

Having received this publication from Barry Miles, John Lennon took it with him on his vacation to Trinidad back in January of 1966. Before his flight, he recorded a spoken word cassette in the attic studio of his new Kenwood home which was to be used for his purpose of personally delving deeper into the LSD experience. In "The Psychedelic Experience," Timothy Leary suggests making such a tape to play back to yourself during an acid trip the moment you sense you're moving into a dangerous course, which was John's experience in past trips. One such occasion was in August of 1965 during the group's stay in Benedict Canyon as related in the song "She Said She Said." With the final chapter of Leary's book in front of him, Lennon recorded the following message to himself: Having received this publication from Barry Miles, John Lennon took it with him on his vacation to Trinidad back in January of 1966. Before his flight, he recorded a spoken word cassette in the attic studio of his new Kenwood home which was to be used for his purpose of personally delving deeper into the LSD experience. In "The Psychedelic Experience," Timothy Leary suggests making such a tape to play back to yourself during an acid trip the moment you sense you're moving into a dangerous course, which was John's experience in past trips. One such occasion was in August of 1965 during the group's stay in Benedict Canyon as related in the song "She Said She Said." With the final chapter of Leary's book in front of him, Lennon recorded the following message to himself:

"O John Lennon - The time has come for you to seek new levels of reality. Your ego and the rock and roll game are about to cease. You are about to set face to face with the Clear Light...That which is called ego-death is coming to you. This is now the hour of death and rebirth...Do not fear it. Surrender to it. Join it. It is part of you. You are part of it...Remember also: Beyond the restless flowing electricity of life is the ultimate reality - The Void."

According to Rolling Stone’s “The Beatles: 100 Greatest Songs” 2010 issue, "Lennon ran a tape recorder and read passages from (the book) as he was flying (to Trinidad). He was soon writing a song using some of the actual lines from Leary, including his description of the state of grace beyond reality. Lennon even used it as a working title: ‘The Void.’" Neil Aspinall, as quoted in a 1966 edition of "The Beatles Book Monthly" fan magazine, informed their readers that the original title of the song was "The Void." As stated in Albert Goldman's book "The Lives Of John Lennon," "The Void" was "the term employed by translators of the 'Tibetan Book Of The Dead' for the region in which the soul finds itself after death." According to Rolling Stone’s “The Beatles: 100 Greatest Songs” 2010 issue, "Lennon ran a tape recorder and read passages from (the book) as he was flying (to Trinidad). He was soon writing a song using some of the actual lines from Leary, including his description of the state of grace beyond reality. Lennon even used it as a working title: ‘The Void.’" Neil Aspinall, as quoted in a 1966 edition of "The Beatles Book Monthly" fan magazine, informed their readers that the original title of the song was "The Void." As stated in Albert Goldman's book "The Lives Of John Lennon," "The Void" was "the term employed by translators of the 'Tibetan Book Of The Dead' for the region in which the soul finds itself after death."

Having taken at least two LSD trips by this time (and undoubtedly taking his third while reading from the book on the plane), Lennon was definitely curious about how to acquire the best experience possible. “Round about this time,” Paul recalls, “people were starting to experiment with drugs, including LSD. John had got hold of Timothy Leary’s adaptation of ‘The Tibetan Book Of The Dead,’ which is a pretty interesting book. For the first time we got the idea that, as with ancient Egyptian practice, when you die you lie in state for a few days, and then some of your handmaidens come and prepare you for a huge voyage. Rather than the British version, in which you just pop your clogs. With LSD, this theme was all the more interesting.” Having taken at least two LSD trips by this time (and undoubtedly taking his third while reading from the book on the plane), Lennon was definitely curious about how to acquire the best experience possible. “Round about this time,” Paul recalls, “people were starting to experiment with drugs, including LSD. John had got hold of Timothy Leary’s adaptation of ‘The Tibetan Book Of The Dead,’ which is a pretty interesting book. For the first time we got the idea that, as with ancient Egyptian practice, when you die you lie in state for a few days, and then some of your handmaidens come and prepare you for a huge voyage. Rather than the British version, in which you just pop your clogs. With LSD, this theme was all the more interesting.”

“Leary was the one going round saying, ‘take it, take it, take it,’” Lennon remembered in 1980, "and we followed his instructions in his ‘how to take a trip’ book. I did it just like he said in the book, and then I wrote ‘Tomorrow Never Knows,’ which was almost the first acid song: ‘Lay down all thought, surrender to the void,’ and all that sh*t which Leary had pinched from ‘The Book Of The Dead.’" As also related in Albert Goldman's book "The Lives Of John Lennon," "Virtually every word and idea in this song...was derived directly from Leary's book, starting with the famous first line, taken verbatim from the instruction for dealing with panic on an acid trip: 'Whenever in doubt, turn off your mind, relax, float downstream.'" “Leary was the one going round saying, ‘take it, take it, take it,’” Lennon remembered in 1980, "and we followed his instructions in his ‘how to take a trip’ book. I did it just like he said in the book, and then I wrote ‘Tomorrow Never Knows,’ which was almost the first acid song: ‘Lay down all thought, surrender to the void,’ and all that sh*t which Leary had pinched from ‘The Book Of The Dead.’" As also related in Albert Goldman's book "The Lives Of John Lennon," "Virtually every word and idea in this song...was derived directly from Leary's book, starting with the famous first line, taken verbatim from the instruction for dealing with panic on an acid trip: 'Whenever in doubt, turn off your mind, relax, float downstream.'"

John's original lyric sheet for the song contains additional lines that were later omitted. These included "And all the colors of the earth you'll hear, it's not thinking, it's not thinking" and "Put down all thought, await the shining void, it is gleaning."

In 1980, Lennon stated: “I read George Martin was saying that John was into ‘The Book Of The Dead.’ I’d never seen it in my life. I just saw Leary’s psychedelic handout. It was very nice in them days.” In actuality, it appears that The Beatles themselves were promoting the song in this way. “The words are from ‘The Tibetan Book Of The Dead,’ so there,” Paul said in an August, 1966 interview. They may have wanted keep the Timothy Leary/drug connections under wraps for the time being this early in their career. In 1980, Lennon stated: “I read George Martin was saying that John was into ‘The Book Of The Dead.’ I’d never seen it in my life. I just saw Leary’s psychedelic handout. It was very nice in them days.” In actuality, it appears that The Beatles themselves were promoting the song in this way. “The words are from ‘The Tibetan Book Of The Dead,’ so there,” Paul said in an August, 1966 interview. They may have wanted keep the Timothy Leary/drug connections under wraps for the time being this early in their career.

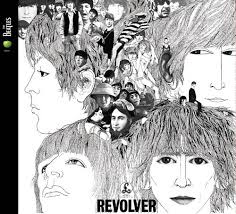

Paul relinquishes any doubt as to who was the entire composer of this track by saying: “The final track on ‘Revolver,’ ‘Tomorrow Never Knows,’ was definitely John’s.” He does, however, remember the song’s first display for all to hear. In his book “Many Years From Now,” Paul states: “I remember John coming to Brian Epstein’s house at 24 Chapel Street, in Belgravia. We got back together after a break, and we were there for a meeting. George Martin was there so it may have been to show George some new songs or talk about the new album. John got his guitar out and started doing ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ and it was all on one chord. This was because of our interest in Indian music. We would be sitting around and at the end of an Indian album we’d go, ‘Did anyone realize they didn’t change chords?’ It would be like ‘Sh*t, it was all in E! Wow, man, that is pretty far out.’ So we began to sponge up a few of these nice ideas.” Paul relinquishes any doubt as to who was the entire composer of this track by saying: “The final track on ‘Revolver,’ ‘Tomorrow Never Knows,’ was definitely John’s.” He does, however, remember the song’s first display for all to hear. In his book “Many Years From Now,” Paul states: “I remember John coming to Brian Epstein’s house at 24 Chapel Street, in Belgravia. We got back together after a break, and we were there for a meeting. George Martin was there so it may have been to show George some new songs or talk about the new album. John got his guitar out and started doing ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ and it was all on one chord. This was because of our interest in Indian music. We would be sitting around and at the end of an Indian album we’d go, ‘Did anyone realize they didn’t change chords?’ It would be like ‘Sh*t, it was all in E! Wow, man, that is pretty far out.’ So we began to sponge up a few of these nice ideas.”

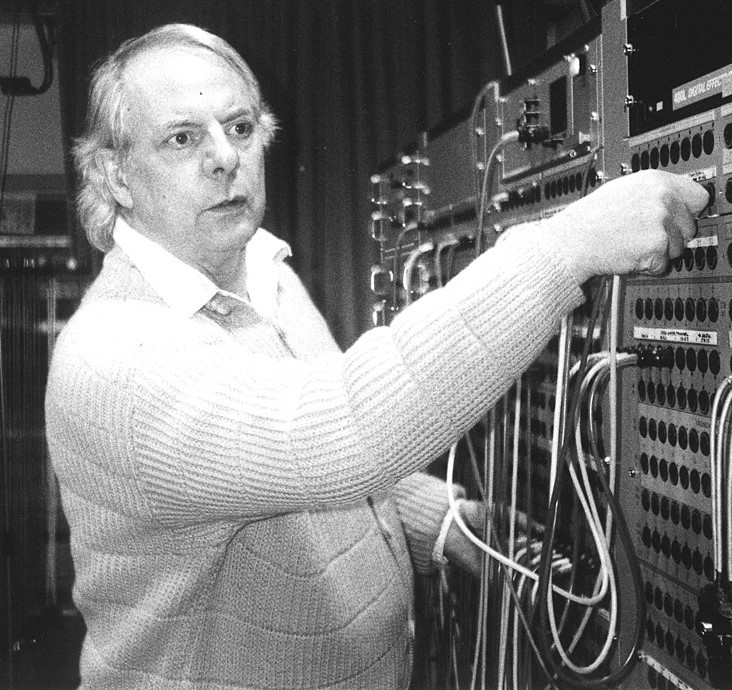

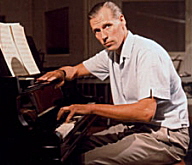

In the book accompanying the 2022 Deluxe editions of "Revolver," Paul McCartney adds: "Normally we'd say to George Martin, 'Here, George, there's this song.' There'd be a few chords, a few lyrics; a few bits of things you could understand: a hook, a riff. But this one was all on C. It never changed off C." In "Many Years From Now," Paul continues: "This is one thing I always gave George Martin great credit for. He was a slightly older man and we were pretty far out, but he didn’t flinch at all when John played it to him, he just said, ‘Hmmm, I see, yes. Hmm hmm.’ He could have said, ‘Bloody hell, it’s terrible!’ I think George was always intrigued to see what direction we’d gone in, probably in his mind thinking, ‘How can I make this into a record?’ But by that point he was starting to trust that we must know vaguely what we were doing, but the material was really outside of his realm.” In the book accompanying the 2022 Deluxe editions of "Revolver," Paul McCartney adds: "Normally we'd say to George Martin, 'Here, George, there's this song.' There'd be a few chords, a few lyrics; a few bits of things you could understand: a hook, a riff. But this one was all on C. It never changed off C." In "Many Years From Now," Paul continues: "This is one thing I always gave George Martin great credit for. He was a slightly older man and we were pretty far out, but he didn’t flinch at all when John played it to him, he just said, ‘Hmmm, I see, yes. Hmm hmm.’ He could have said, ‘Bloody hell, it’s terrible!’ I think George was always intrigued to see what direction we’d gone in, probably in his mind thinking, ‘How can I make this into a record?’ But by that point he was starting to trust that we must know vaguely what we were doing, but the material was really outside of his realm.”

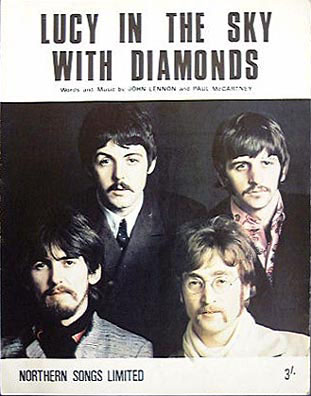

Claiming it as “my first psychedelic song” in 1972, Lennon created the first Beatles track with obvious LSD overtones, contrary to what most people would think. “That was an LSD song,” said McCartney in 1984, adding, “Probably the only one. People always thought ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’ was but it actually wasn’t meant to say LSD.” Claiming it as “my first psychedelic song” in 1972, Lennon created the first Beatles track with obvious LSD overtones, contrary to what most people would think. “That was an LSD song,” said McCartney in 1984, adding, “Probably the only one. People always thought ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’ was but it actually wasn’t meant to say LSD.”

“The Void” was apparently a little too deep of a title for the song, so John looked elsewhere to name his masterpiece. “I took one of Ringo’s malapropisms as the title,” he explains, “to take the edge off the heavy philosophical lyrics.” George stated: “Ringo would always say grammatically incorrect phrases and we’d all laugh.” Ringo explained: “I used to, while I was saying one thing, have another thing come into my brain and then move down fast. 'Tomorrow Never Knows' was something I said. God knows where it came from. John used to like them most. He always used to write them down. I seem to be better now.”

An interview by David Coleman of BBC TV on February 22nd, 1964 does well in shedding some light on when Ringo first used the phrase. When asked to relate the circumstances at the Embassy Ball at the British Embassy in Washington, DC, where someone reportedly snipped off some of his hair with a pair of scissors, Ringo responded: “I was just talking, having an interview…and I looked ‘round, and there were about 400 people just smiling. So, y'know, what can you say?” John: “What Can You Say?” Ringo: "Tomorrow never knows." An interview by David Coleman of BBC TV on February 22nd, 1964 does well in shedding some light on when Ringo first used the phrase. When asked to relate the circumstances at the Embassy Ball at the British Embassy in Washington, DC, where someone reportedly snipped off some of his hair with a pair of scissors, Ringo responded: “I was just talking, having an interview…and I looked ‘round, and there were about 400 people just smiling. So, y'know, what can you say?” John: “What Can You Say?” Ringo: "Tomorrow never knows."

Regarding the life The Beatles were experiencing in 1966, Paul stated, "I think what happened was that we came down from the North, experienced London where quite experimental things were happening and we always thought the people back home would love to know this. So we felt like we were the megaphone. If it was happening to us and we like it, we should let them know, because they're not here hanging out with the artists. It would be good to pass on the good news. I think that was one of the great values of what we did, we showed what we were going through to the world." Regarding the life The Beatles were experiencing in 1966, Paul stated, "I think what happened was that we came down from the North, experienced London where quite experimental things were happening and we always thought the people back home would love to know this. So we felt like we were the megaphone. If it was happening to us and we like it, we should let them know, because they're not here hanging out with the artists. It would be good to pass on the good news. I think that was one of the great values of what we did, we showed what we were going through to the world."

Recording History

As was usually the case in The Beatles recording history, the first song to be tackled for a new album was a Lennon creation. April 6th, 1966 was that first session for what became the “Revolver” album, the session beginning at 8 pm in EMI Studio Three. Interestingly, the date written on the tape box of this first "Revolver" session was March 6th, 1966, although all other documentation stipulates April 6th as when this recording took place.

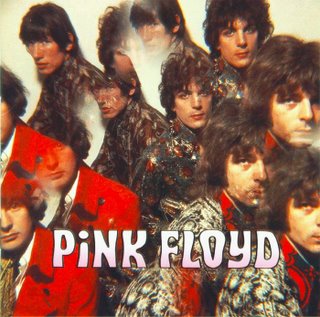

One noteworthy new development in Beatles history that occurred on this day was the employ of 20-year-old Geoff Emerick as primary engineer. Norman Smith had been The Beatles engineer for the vast majority of their sessions up to this point but, because of his promotion to producer (new band Pink Floyd being one of his first artists), advantage was taken to get some "young blood" in the studio to help satisfy The Beatles’ cravings for innovations in the recording process. Having worked with them on various occasions in the past as second engineer, the group was somewhat familiar with him personally. His new role as primary engineer would test his creativity and ultimately win them over as one who could fulfill their quest for expanding the sonic landscape. One noteworthy new development in Beatles history that occurred on this day was the employ of 20-year-old Geoff Emerick as primary engineer. Norman Smith had been The Beatles engineer for the vast majority of their sessions up to this point but, because of his promotion to producer (new band Pink Floyd being one of his first artists), advantage was taken to get some "young blood" in the studio to help satisfy The Beatles’ cravings for innovations in the recording process. Having worked with them on various occasions in the past as second engineer, the group was somewhat familiar with him personally. His new role as primary engineer would test his creativity and ultimately win them over as one who could fulfill their quest for expanding the sonic landscape.

Being such a landmark day in his early career, Geoff Emerick recalls the events of this day with exceptional clarity, his book “Here, There And Everywhere” giving amazing detail and is a must read to get a full picture, highlights of which I’ll include here. Engineer Geoff Emerick explains: “John was deep in discussion with George Martin, clearly the first song we were going to be working on was one of his. He had no title for it at the time, so the tape box was simply labeled 'Mark I.'” He apparently later had misgivings about using the title “The Void” as roadie Neil Aspinall leaked to the world through the group’s monthly fan magazine. Being such a landmark day in his early career, Geoff Emerick recalls the events of this day with exceptional clarity, his book “Here, There And Everywhere” giving amazing detail and is a must read to get a full picture, highlights of which I’ll include here. Engineer Geoff Emerick explains: “John was deep in discussion with George Martin, clearly the first song we were going to be working on was one of his. He had no title for it at the time, so the tape box was simply labeled 'Mark I.'” He apparently later had misgivings about using the title “The Void” as roadie Neil Aspinall leaked to the world through the group’s monthly fan magazine.

Geoff Emerick continues: “'This one’s completely different than anything we’ve ever done before,' John was saying to George Martin. ‘It’s only got the one chord, and the whole thing is meant to be like a drone.’ My ears perked up when I heard John’s final direction to George: ‘and I want my voice to sound like the Dalai Lama chanting from a mountaintop, miles away.’” Lennon explained in 1967: “I’d imagined, in my head, that in the background you could hear thousands of monks chanting. That was impractical, of course, and we did something different. I should have tried to get near my original idea, the monks singing. I realize now that was what I wanted.” Geoff Emerick continues: “'This one’s completely different than anything we’ve ever done before,' John was saying to George Martin. ‘It’s only got the one chord, and the whole thing is meant to be like a drone.’ My ears perked up when I heard John’s final direction to George: ‘and I want my voice to sound like the Dalai Lama chanting from a mountaintop, miles away.’” Lennon explained in 1967: “I’d imagined, in my head, that in the background you could hear thousands of monks chanting. That was impractical, of course, and we did something different. I should have tried to get near my original idea, the monks singing. I realize now that was what I wanted.”

George Martin relates: “So, I thought, ‘I wonder what time the next plane is to Tibet.’ But, I thought, that was one way of doing it.” Geoff Emerick continues, "George Martin looked over at me with a nod and he reassured John. ‘Got it. I’m sure Geoff and I will come up with something.’ Which meant, of course, that he was sure Geoff would come up with something. I looked around the room in a panic. I thought I had a vague idea of what John wanted, but I had no clear sense of how to achieve it." George Martin relates: “So, I thought, ‘I wonder what time the next plane is to Tibet.’ But, I thought, that was one way of doing it.” Geoff Emerick continues, "George Martin looked over at me with a nod and he reassured John. ‘Got it. I’m sure Geoff and I will come up with something.’ Which meant, of course, that he was sure Geoff would come up with something. I looked around the room in a panic. I thought I had a vague idea of what John wanted, but I had no clear sense of how to achieve it."

As detailed in the book contained in the 2022 Deluxe editions of "Revolver," George Martin remembers: "I knew that ordinary echo or reverb wouldn't work, because it would just be a very distant voice. We needed to have something a bit weird and metallic. I've never been to Tibet, but when I thought of Dalai Lama, I thought of Alpen horns and I imagined what the voice would sound like coming out of one of those long horns." In the meantime, John wanted to make a tape loop of himself on guitar and Ringo on drums, an innovation that fortunately George Martin was familiar with, especially with his 1962 Ray Cathode release entitled "Time Beat." "I used to do a lot of experimenting with musique concrete, speeding up tapes, making funny noises and plucking piano strings, that kind of thing." "Paul and I are very keen on this electronic music," John said in March of 1966 after Paul had been introduced to the manipulation and editing of tape recordings by Luciano Berio the previous month. Lennon continued: "You make it clinking a couple of glasses together or bleeps from the radio, then you loop the tape to repeat the noises at intervals. Some people build up whole symphonies from it." As detailed in the book contained in the 2022 Deluxe editions of "Revolver," George Martin remembers: "I knew that ordinary echo or reverb wouldn't work, because it would just be a very distant voice. We needed to have something a bit weird and metallic. I've never been to Tibet, but when I thought of Dalai Lama, I thought of Alpen horns and I imagined what the voice would sound like coming out of one of those long horns." In the meantime, John wanted to make a tape loop of himself on guitar and Ringo on drums, an innovation that fortunately George Martin was familiar with, especially with his 1962 Ray Cathode release entitled "Time Beat." "I used to do a lot of experimenting with musique concrete, speeding up tapes, making funny noises and plucking piano strings, that kind of thing." "Paul and I are very keen on this electronic music," John said in March of 1966 after Paul had been introduced to the manipulation and editing of tape recordings by Luciano Berio the previous month. Lennon continued: "You make it clinking a couple of glasses together or bleeps from the radio, then you loop the tape to repeat the noises at intervals. Some people build up whole symphonies from it."

With this new innovation in mind, Lennon pushed to start the recording of his new composition. Geoff Emerick continues: "Fortunately, I had a little time to think about it, because John decided to start the recording process by having me make a (tape) loop of him playing a simple guitar figure, with Ringo accompanying him on drums. Because Lennon wanted a thunderous sound, the decision was made to play the part at a fast tempo and then slow the tape down on playback. This would serve not only to return the tempo to the desired speed but also to make the guitar and drums, and the reverb they were drenched in, sound otherworldly." When this original recording was played back to The Beatles in 1995 during the making of their Anthology series, George Harrison remarked, "What's that underwater sound?" The guitarist obviously forgot how the sound was made nearly three decades earlier. Paul also experimented with playing some piano on the song which got caught on tape, although it was decided not to be appropriate for the song…at least at this point. With this new innovation in mind, Lennon pushed to start the recording of his new composition. Geoff Emerick continues: "Fortunately, I had a little time to think about it, because John decided to start the recording process by having me make a (tape) loop of him playing a simple guitar figure, with Ringo accompanying him on drums. Because Lennon wanted a thunderous sound, the decision was made to play the part at a fast tempo and then slow the tape down on playback. This would serve not only to return the tempo to the desired speed but also to make the guitar and drums, and the reverb they were drenched in, sound otherworldly." When this original recording was played back to The Beatles in 1995 during the making of their Anthology series, George Harrison remarked, "What's that underwater sound?" The guitarist obviously forgot how the sound was made nearly three decades earlier. Paul also experimented with playing some piano on the song which got caught on tape, although it was decided not to be appropriate for the song…at least at this point.

To create the proposed tape loop, Lennon recorded a rhythm guitar part through a Leslie speaker, Ringo played drums, and even George Harrison got in on the act by playing a fuzz tone electric guitar riff, all of this being performed at a very fast tempo with the intention of it later being slowed down when a two-measure loop was procured from this recording. Once an appropriate two-measure section was isolated and cut out for a loop to be made, this section was played back at half speed and recorded onto track one of another four-track tape with Ringo providing another drum pattern on top of it, "like doing a rhumba" as George and Ringo described it in 1995 during the filming of their "Anthology" series. To create the proposed tape loop, Lennon recorded a rhythm guitar part through a Leslie speaker, Ringo played drums, and even George Harrison got in on the act by playing a fuzz tone electric guitar riff, all of this being performed at a very fast tempo with the intention of it later being slowed down when a two-measure loop was procured from this recording. Once an appropriate two-measure section was isolated and cut out for a loop to be made, this section was played back at half speed and recorded onto track one of another four-track tape with Ringo providing another drum pattern on top of it, "like doing a rhumba" as George and Ringo described it in 1995 during the filming of their "Anthology" series.

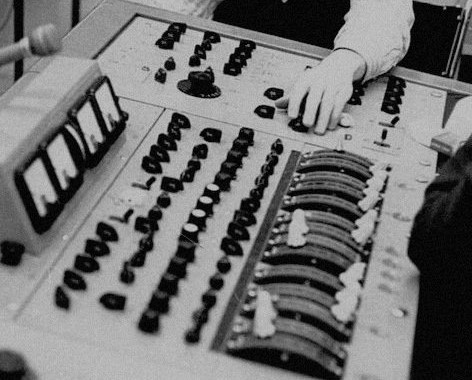

Simultaneous to Ringo playing the basic "rhumba" drum pattern on track one along with the tape loop was John overdubbing lead vocals onto track four of the tape, but using an innovative new effect. Geoff Emerick explains further: "The studio’s Hammond organ was hooked up to a system called a Leslie, which was a large wooden box that contained an amp and two sets of revolving speakers, one that carried low bass frequencies and the other that carried high treble frequencies...Nobody had ever put a vocal through it...’I think I have an idea about what to do for John’s voice,’ I announced to George in the control room as we finished editing the loop. Excitedly, I explained my concept to him. Though his brows furrowed for a moment, he nodded his assent. Then he went out into the studio and told the four Beatles, who were standing around impatiently waiting for the loop to be constructed, to take a tea break while ‘Geoff sorts out something for the vocal.’” Simultaneous to Ringo playing the basic "rhumba" drum pattern on track one along with the tape loop was John overdubbing lead vocals onto track four of the tape, but using an innovative new effect. Geoff Emerick explains further: "The studio’s Hammond organ was hooked up to a system called a Leslie, which was a large wooden box that contained an amp and two sets of revolving speakers, one that carried low bass frequencies and the other that carried high treble frequencies...Nobody had ever put a vocal through it...’I think I have an idea about what to do for John’s voice,’ I announced to George in the control room as we finished editing the loop. Excitedly, I explained my concept to him. Though his brows furrowed for a moment, he nodded his assent. Then he went out into the studio and told the four Beatles, who were standing around impatiently waiting for the loop to be constructed, to take a tea break while ‘Geoff sorts out something for the vocal.’”

After the required wiring was put in place, two microphones were positioned near the speakers and tests were run. The Beatles were then informed that they were ready to give it a try. "John settled behind the mic and Ringo behind his kit, ready to overdub vocals and drums on top of the recorded loop,” Geoff Emerick continues. “Paul and George Harrison headed up to the control room. Once everyone was in place and ready to go, George Martin got on the talkback mic: ‘Stand by…here it comes.’ Then Phil (McDonald) started the loop playing back. Ringo began playing along, hitting the drums with a fury, and John began singing, eyes closed, head back." As stated above, John's vocals were recorded onto track four of the four-track tape, while Ringo's drums were recorded onto track one while the tape loop, which was also allocated to track one, was being played back at half speed. "Famous organists like Ethal Smith used (the Leslie effect) as part of their technique," George Martin explained, "varying the vibrato of it by altering the speed. Putting John's voice through that...gave a kind of vibrato intermittent effect." After the required wiring was put in place, two microphones were positioned near the speakers and tests were run. The Beatles were then informed that they were ready to give it a try. "John settled behind the mic and Ringo behind his kit, ready to overdub vocals and drums on top of the recorded loop,” Geoff Emerick continues. “Paul and George Harrison headed up to the control room. Once everyone was in place and ready to go, George Martin got on the talkback mic: ‘Stand by…here it comes.’ Then Phil (McDonald) started the loop playing back. Ringo began playing along, hitting the drums with a fury, and John began singing, eyes closed, head back." As stated above, John's vocals were recorded onto track four of the four-track tape, while Ringo's drums were recorded onto track one while the tape loop, which was also allocated to track one, was being played back at half speed. "Famous organists like Ethal Smith used (the Leslie effect) as part of their technique," George Martin explained, "varying the vibrato of it by altering the speed. Putting John's voice through that...gave a kind of vibrato intermittent effect."

“'Turn off your mind, relax and float downstream' Lennon’s voice sounded like it never had before, eerily disconnected, distant yet compelling. The effect seemed to perfectly complement the esoteric lyrics he was chanting. Everyone in the control room looked stunned. Through the glass we could see John begin smiling. At the end of the first verse, Lennon gave an exuberant thumbs-up and McCartney and Harrison began slapping each other on the back. ‘It’s the Dalai Lennon!’ Paul shouted…’That is bloody marvelous,’ (John) kept saying over and over again." “'Turn off your mind, relax and float downstream' Lennon’s voice sounded like it never had before, eerily disconnected, distant yet compelling. The effect seemed to perfectly complement the esoteric lyrics he was chanting. Everyone in the control room looked stunned. Through the glass we could see John begin smiling. At the end of the first verse, Lennon gave an exuberant thumbs-up and McCartney and Harrison began slapping each other on the back. ‘It’s the Dalai Lennon!’ Paul shouted…’That is bloody marvelous,’ (John) kept saying over and over again."

“John was so impressed by the sound of a Leslie that he hit upon the reverse idea,” Geoff Emerick recalls in the book “The Beatles Recording Sessions.” “He suggested we suspend him from a rope in the middle of the studio ceiling, put a mike in the middle of the floor, give him a push and he’d sing as he went around and around. That was one idea that didn’t come off although they were always said to be ‘looking into it’!” Mark Lewisohn described this recording in "The Beatles Recording Sessions" as “a sensational, apocalyptic version…a heavy metal recording of enormous proportion, with thundering echo and booming, quivering, ocean-bed vibrations.” "Now, that's alternative! That's cool!", Paul explaimed while listening to a playback of this early version of the song during his 2021 Hulu series "McCartney 3,2,1." "Pretty stoned, if you ask me! As time went on we had much more freedom. We had much longer to do things. But it actually spurred us on to do some new stuff, so the drum sound on this is, I love it! It's a really great Ringo sound." “John was so impressed by the sound of a Leslie that he hit upon the reverse idea,” Geoff Emerick recalls in the book “The Beatles Recording Sessions.” “He suggested we suspend him from a rope in the middle of the studio ceiling, put a mike in the middle of the floor, give him a push and he’d sing as he went around and around. That was one idea that didn’t come off although they were always said to be ‘looking into it’!” Mark Lewisohn described this recording in "The Beatles Recording Sessions" as “a sensational, apocalyptic version…a heavy metal recording of enormous proportion, with thundering echo and booming, quivering, ocean-bed vibrations.” "Now, that's alternative! That's cool!", Paul explaimed while listening to a playback of this early version of the song during his 2021 Hulu series "McCartney 3,2,1." "Pretty stoned, if you ask me! As time went on we had much more freedom. We had much longer to do things. But it actually spurred us on to do some new stuff, so the drum sound on this is, I love it! It's a really great Ringo sound."

However, as evidenced by this recording being included on both "Anthology 2" and Deluxe editions of "Revolver," Ringo's drums and John's vocals increasingly got off tempo with the tape loop, untimately deeming this take unusable for the finished product. A decision was quickly made to start the song from scratch. They, of course, were anxious to reinstitute the Leslie vocal effect for the finished product. More ideas were flowing at this point. "While they were listening to the first playback, John and George Harrison had been excitedly discussing ideas for guitar parts," continues Geoff Emerick. "Harrison eagerly suggested that a tamboura – one of his new collection of Indian instruments – be added. ‘It’s perfect for this track, John,’ he was explaining in his deadpan monotone. ‘It’s just kind of a droning sound and I think it will make the whole thing quite Eastern.’ Lennon was nodding his head. You could tell he liked the idea." However, as evidenced by this recording being included on both "Anthology 2" and Deluxe editions of "Revolver," Ringo's drums and John's vocals increasingly got off tempo with the tape loop, untimately deeming this take unusable for the finished product. A decision was quickly made to start the song from scratch. They, of course, were anxious to reinstitute the Leslie vocal effect for the finished product. More ideas were flowing at this point. "While they were listening to the first playback, John and George Harrison had been excitedly discussing ideas for guitar parts," continues Geoff Emerick. "Harrison eagerly suggested that a tamboura – one of his new collection of Indian instruments – be added. ‘It’s perfect for this track, John,’ he was explaining in his deadpan monotone. ‘It’s just kind of a droning sound and I think it will make the whole thing quite Eastern.’ Lennon was nodding his head. You could tell he liked the idea."

"But my attention was drawn to Paul and Ringo, who were huddled together talking about the drumming," relates Geoff Emerick." "Paul was suggesting that ‘Ring’ (as we usually called him) add a little skip to the basic beat he was playing. The pattern he was tapping out on the mixing console was somewhat reminiscent of the one Ringo had played on their recent hit single ‘Ticket To Ride.’ Ringo said little, but listened intently. He was used to taking direction from the others." "But my attention was drawn to Paul and Ringo, who were huddled together talking about the drumming," relates Geoff Emerick." "Paul was suggesting that ‘Ring’ (as we usually called him) add a little skip to the basic beat he was playing. The pattern he was tapping out on the mixing console was somewhat reminiscent of the one Ringo had played on their recent hit single ‘Ticket To Ride.’ Ringo said little, but listened intently. He was used to taking direction from the others."

With the determination to create a new sound for Beatles recordings, following the earlier admonition from John about the song being “completely different than anything we’ve ever done before,” Geoff Emerick decided to break standard EMI procedures and mic Ringo's drums differently. “Without saying a word, I quietly slipped out to the studio and moved both the snare drum mic and the single overhead mic in close. But before I also moved the microphone that was aimed at Ringo’s bass drum, there was something else I wanted to try, because I felt that the bass drum was ringing too much…Sitting atop one of the instrument cases was an old woolen sweater – one which had been specially knitted with eight arms to promote the group’s recent film, which was originally called ‘Eight Arms To Hold You’…I removed the bass drum’s front skin – the one with the famous ‘dropped-T’ Beatles logo on it – and stuffed the sweater inside so that it was flush against the rear beater skin. Then I replaced the front skin and positioned the bass drum mic directly in front of it, angled down slightly but so close that it was almost touching.” With the determination to create a new sound for Beatles recordings, following the earlier admonition from John about the song being “completely different than anything we’ve ever done before,” Geoff Emerick decided to break standard EMI procedures and mic Ringo's drums differently. “Without saying a word, I quietly slipped out to the studio and moved both the snare drum mic and the single overhead mic in close. But before I also moved the microphone that was aimed at Ringo’s bass drum, there was something else I wanted to try, because I felt that the bass drum was ringing too much…Sitting atop one of the instrument cases was an old woolen sweater – one which had been specially knitted with eight arms to promote the group’s recent film, which was originally called ‘Eight Arms To Hold You’…I removed the bass drum’s front skin – the one with the famous ‘dropped-T’ Beatles logo on it – and stuffed the sweater inside so that it was flush against the rear beater skin. Then I replaced the front skin and positioned the bass drum mic directly in front of it, angled down slightly but so close that it was almost touching.”

Shortly afterwards, "take two" began, this rhythm track consisting of Paul on his Rickenbacker bass and Ringo on drums allocated to track one while Lennon's vocals and Harrison on tambourine were recorded onto track four. “'Ready John?' asked (George) Martin. A nod from Lennon signaled that he was about to begin his count-in, so I instructed (2nd engineer) Phil McDonald to roll tape. ‘…two, three, four,’ intoned John, and then Ringo entered with a furious cymbal crash and bass drum hit. It sounded magnificent! Thirty seconds in, though, someone in the band made a mistake and they all stopped...I quickly announced 'take three' on the talkback mic and the group began playing the song again, perfectly this time around. 'I think we’ve got it,' John announced excitedly after the last note dies away. George Martin waved everyone into the control room to hear the playback…’What on earth did you do to my drums?’ Ringo was asking me. ‘They sound fantastic!’ Paul and John began whooping it up, and even the normally dour Harrison was smiling broadly. ‘That’s the one, boys,’ George Martin agreed, nodding in my direction.” Shortly afterwards, "take two" began, this rhythm track consisting of Paul on his Rickenbacker bass and Ringo on drums allocated to track one while Lennon's vocals and Harrison on tambourine were recorded onto track four. “'Ready John?' asked (George) Martin. A nod from Lennon signaled that he was about to begin his count-in, so I instructed (2nd engineer) Phil McDonald to roll tape. ‘…two, three, four,’ intoned John, and then Ringo entered with a furious cymbal crash and bass drum hit. It sounded magnificent! Thirty seconds in, though, someone in the band made a mistake and they all stopped...I quickly announced 'take three' on the talkback mic and the group began playing the song again, perfectly this time around. 'I think we’ve got it,' John announced excitedly after the last note dies away. George Martin waved everyone into the control room to hear the playback…’What on earth did you do to my drums?’ Ringo was asking me. ‘They sound fantastic!’ Paul and John began whooping it up, and even the normally dour Harrison was smiling broadly. ‘That’s the one, boys,’ George Martin agreed, nodding in my direction.”

So ended the recording session for the eveing, the rhythm track being completed with Lennon's vocals being performed in the conventional single-tracked manner for the first three lyrical phrases of the song and then through the rotating Leslie speaker for the remainder. All overdubs were left over for the following session on the next day. However, before this session ended at 1:15 am, an assignment of sorts was given to each of the group to prepare for the next day's recording session. So ended the recording session for the eveing, the rhythm track being completed with Lennon's vocals being performed in the conventional single-tracked manner for the first three lyrical phrases of the song and then through the rotating Leslie speaker for the remainder. All overdubs were left over for the following session on the next day. However, before this session ended at 1:15 am, an assignment of sorts was given to each of the group to prepare for the next day's recording session.

“Everybody went home and made up a spool, a loop,” explains George Harrison. "'OK, class, now I want you all to go home and come back in the morning with your own loop.' We were touching on the Stockhausen kind of ‘avant garde a clue’ music." “Everybody went home and made up a spool, a loop,” explains George Harrison. "'OK, class, now I want you all to go home and come back in the morning with your own loop.' We were touching on the Stockhausen kind of ‘avant garde a clue’ music."

"You know that you could talk to George (Martin) about these things," McCartney explained in his 2021 Hulu documentary. "'George, what if we played it backwards and then what if we did that?' 'Well...' and he'd sort of would go along with it. Because a lot of other producers at EMI, I'm sure they would have just said, 'Another time, let's get the record done,' y'know, and wouldn't have been interested in backwards noises or tape loops. I had an old tape recorder that you could put, make a loop instead of the two reels of tape. You could (make) a little loop that would go round and round and round. There's a little button that says, 'superimpose.' It keeps recording forever and ever and ever and ever. Now, once you've gone 'round, what was there is still there but it's now going in the background a bit. It's a bit of an art because you've got to know when to stop...you gotta sort of stop soon because you're gonna wipe out those original ideas."”

“It was Paul, actually, who experimented with his tape machine at home,” remembers George Martin, “taking the erase-head off and putting on loops, saturating the tape with weird sounds. He explained to the boys how he had done this and Ringo and George would do the same and bring me different loops of sounds. I probably had about 40 or 50 tapes they brought in to me. I listened to each one at different speeds and backwards. Some were absolute rubish, no good at all, some were very interesting. So we selected the ones we thought were good.” “It was Paul, actually, who experimented with his tape machine at home,” remembers George Martin, “taking the erase-head off and putting on loops, saturating the tape with weird sounds. He explained to the boys how he had done this and Ringo and George would do the same and bring me different loops of sounds. I probably had about 40 or 50 tapes they brought in to me. I listened to each one at different speeds and backwards. Some were absolute rubish, no good at all, some were very interesting. So we selected the ones we thought were good.”

“I was into tape loops at the time,” explains McCartney. “I had two Brennell machines and I could create tape loops with them...I used to get a lot of seagulls in my loops; a speeded-up shout, hah ha, goes squawk squawk. And I always get pictures of seasides, of Torquay, The Torbay Inn, fishing boats and puffins and deep purple mountains. Those were the slowed-down ones.” “I was into tape loops at the time,” explains McCartney. “I had two Brennell machines and I could create tape loops with them...I used to get a lot of seagulls in my loops; a speeded-up shout, hah ha, goes squawk squawk. And I always get pictures of seasides, of Torquay, The Torbay Inn, fishing boats and puffins and deep purple mountains. Those were the slowed-down ones.”

“So we made up our little loops and brought them to the studio,” George Harrison recalls. “Those ‘seagulls’ were just weird noises. I don’t exactly recall what was on my loop. I think it was a grandfather clock, but at a different speed. You could do it with anything: pick a little piece and then edit it, connect it up to itself and play it at a different speed.” “So we made up our little loops and brought them to the studio,” George Harrison recalls. “Those ‘seagulls’ were just weird noises. I don’t exactly recall what was on my loop. I think it was a grandfather clock, but at a different speed. You could do it with anything: pick a little piece and then edit it, connect it up to itself and play it at a different speed.”

Even Ringo put in some effort. “I had my own little set-up to record them. As George says, we were ‘drinking a lot of tea’ in those days, and on all my tapes you can hear, ‘Oh, I hope I’ve switched it on.’ I’d get so deranged from strong tea. I’d sit there for hours making those noises.” Even Ringo put in some effort. “I had my own little set-up to record them. As George says, we were ‘drinking a lot of tea’ in those days, and on all my tapes you can hear, ‘Oh, I hope I’ve switched it on.’ I’d get so deranged from strong tea. I’d sit there for hours making those noises.”

Geoff Emerick explains the process of making these tape loops in even more detail: “Paul…had discovered that the erase head could be removed, which allowed new sounds to be added to the existing ones each time the tape passed over the record head. Because of the primitive technology of the time, the tape quickly became saturated with sound and distorted, but it was an effect that appealed to the four of them as they conducted sonic experiments in their respective homes.” Geoff Emerick explains the process of making these tape loops in even more detail: “Paul…had discovered that the erase head could be removed, which allowed new sounds to be added to the existing ones each time the tape passed over the record head. Because of the primitive technology of the time, the tape quickly became saturated with sound and distorted, but it was an effect that appealed to the four of them as they conducted sonic experiments in their respective homes.”

At 2:30 pm on the following day, April 7th, 1966, The Beatles convened in EMI Studio Three once again armed and ready to add numerous overdubs to the previous day's rhythm track. “Paul had gone home and sat up all night creating a whole series of short tape loops specifically for the song,” says Geoff Emerick, “which he dutifully presented to me in a little plastic bag when he returned for the next day’s session. We began the second evening’s work by having Phil McDonald carefully thread each loop onto the tape machine, one at a time, so that we could audition them. Paul had assembled an extraordinary collection of bizarre sounds, which included his playing distorted guitar and bass, as well as wineglasses ringing and other indecipherable noises. We played them every conceivable way: proper speed, sped up, slowed down, backwards, forwards. Every now and then, one of The Beatles would shout, ‘That’s a good one,’ as we played through the lot. Eventually five of the loops were selected to be added to the basic backing track.” At 2:30 pm on the following day, April 7th, 1966, The Beatles convened in EMI Studio Three once again armed and ready to add numerous overdubs to the previous day's rhythm track. “Paul had gone home and sat up all night creating a whole series of short tape loops specifically for the song,” says Geoff Emerick, “which he dutifully presented to me in a little plastic bag when he returned for the next day’s session. We began the second evening’s work by having Phil McDonald carefully thread each loop onto the tape machine, one at a time, so that we could audition them. Paul had assembled an extraordinary collection of bizarre sounds, which included his playing distorted guitar and bass, as well as wineglasses ringing and other indecipherable noises. We played them every conceivable way: proper speed, sped up, slowed down, backwards, forwards. Every now and then, one of The Beatles would shout, ‘That’s a good one,’ as we played through the lot. Eventually five of the loops were selected to be added to the basic backing track.”

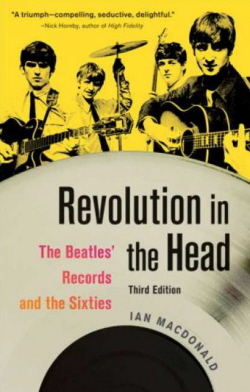

According to Ian MacDonald’s book “Revolution In The Head,” the five loops, numbered according to their first appearance in the song, can be identified as follows: “(1) a ‘seagull’/’Red Indian’ effect (actually McCartney laughing - "Ah, ah, ah, ah") made, like most of the other loops, by superimposition and acceleration (0:07); (2) an orchestral chord (from a record) of B flat major (0:19); (3) a Mellotron played on its flute setting (0:22); (4) another Mellotron oscillating in 6/8 from B flat to C on its string setting (0:38) and (5) a rising scalar phrase on a sitar, recorded with heavy saturation and acceleration (played backwards) (0:56).” Since the fifth of these loops was made on a sitar, we can rightfully assume that this was the creation of George Harrison, debunking the credit from Geoff Emerick that Paul supplied all of the loops used on the song. Or, as some claim, this sitar-like phrase may have been played on the guitar and could possibly have also been recorded and supplied by Paul. However, neither the “wineglasses” loop nor the "grandfather clock" loop were deemed good enough to make the final cut. According to Ian MacDonald’s book “Revolution In The Head,” the five loops, numbered according to their first appearance in the song, can be identified as follows: “(1) a ‘seagull’/’Red Indian’ effect (actually McCartney laughing - "Ah, ah, ah, ah") made, like most of the other loops, by superimposition and acceleration (0:07); (2) an orchestral chord (from a record) of B flat major (0:19); (3) a Mellotron played on its flute setting (0:22); (4) another Mellotron oscillating in 6/8 from B flat to C on its string setting (0:38) and (5) a rising scalar phrase on a sitar, recorded with heavy saturation and acceleration (played backwards) (0:56).” Since the fifth of these loops was made on a sitar, we can rightfully assume that this was the creation of George Harrison, debunking the credit from Geoff Emerick that Paul supplied all of the loops used on the song. Or, as some claim, this sitar-like phrase may have been played on the guitar and could possibly have also been recorded and supplied by Paul. However, neither the “wineglasses” loop nor the "grandfather clock" loop were deemed good enough to make the final cut.

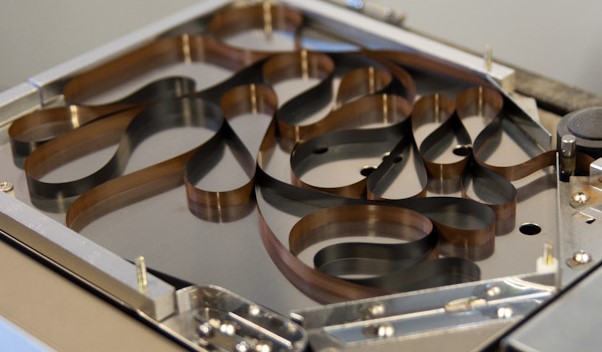

Then came the dilemma of inserting these loops into the recording. "We had six fellows with pencils holding them on, on six machines," explained John back in 1966. "Very desirable, the whole effect, I thought.” Paul adds: "We got machines from all the other studios, and with pencils and the aid of glasses got all the loops to run. We might have had twelve recording machines where we normally only needed one to make a record. We were running with those loops all fed through the recording desk." Beatles road managers Mal Evans and Neil Aspinall were among those in attendance that day holding pencils or glasses to run the tape loops into the tape machines, as was Beatles chauffeur Alf Bicknell. "It was a great laugh," Alf Bicknell writes in his book "Baby, You Can Drive My Car!," adding, "and we were all falling about. John was being just as silly, and wanted to pile the furniture up, so he could stand at the top, and pretend he was singing from the mountains, along with his monks." Then came the dilemma of inserting these loops into the recording. "We had six fellows with pencils holding them on, on six machines," explained John back in 1966. "Very desirable, the whole effect, I thought.” Paul adds: "We got machines from all the other studios, and with pencils and the aid of glasses got all the loops to run. We might have had twelve recording machines where we normally only needed one to make a record. We were running with those loops all fed through the recording desk." Beatles road managers Mal Evans and Neil Aspinall were among those in attendance that day holding pencils or glasses to run the tape loops into the tape machines, as was Beatles chauffeur Alf Bicknell. "It was a great laugh," Alf Bicknell writes in his book "Baby, You Can Drive My Car!," adding, "and we were all falling about. John was being just as silly, and wanted to pile the furniture up, so he could stand at the top, and pretend he was singing from the mountains, along with his monks."

“Fortunately, there were plenty of other machines in the Abbey Road complex,” Geoff Emerick relates, “all interconnected via wiring in the walls, and all the other studios just happened to be empty that afternoon. What followed next was a scene that could have come out a science fiction movie – or a Monty Python sketch. Every tape machine in every studio was commandeered and every available EMI employee was given the task of holding a pencil or drinking glass to give the tape loops the proper tensioning. In many instances, this meant they had to be standing out in the hallway, looking quite sheepish. Most of those people didn’t have a clue what we were doing; they probably thought we were daft…add in the fact that all of the technical staff were required to wear white lab coats, and the whole thing became totally surreal.” “Fortunately, there were plenty of other machines in the Abbey Road complex,” Geoff Emerick relates, “all interconnected via wiring in the walls, and all the other studios just happened to be empty that afternoon. What followed next was a scene that could have come out a science fiction movie – or a Monty Python sketch. Every tape machine in every studio was commandeered and every available EMI employee was given the task of holding a pencil or drinking glass to give the tape loops the proper tensioning. In many instances, this meant they had to be standing out in the hallway, looking quite sheepish. Most of those people didn’t have a clue what we were doing; they probably thought we were daft…add in the fact that all of the technical staff were required to wear white lab coats, and the whole thing became totally surreal.”

"Meanwhile, back in the control room, George Martin and I huddled over the console, raising and lowering faders to the shouted instructions from John, Paul, George and Ringo. (‘Let’s have that seagull sound now!’...) With each fader carrying a different loop, the mixing desk acted like a synthesizer, and we played it like a musical instrument, too, carefully overdubbing textures to the prerecorded backing track. Finally we completed the task to the band’s satisfaction, the white-coated technicians were freed from their labors, and (the) loops were retured back to the plastic bag, never to be played again." "Meanwhile, back in the control room, George Martin and I huddled over the console, raising and lowering faders to the shouted instructions from John, Paul, George and Ringo. (‘Let’s have that seagull sound now!’...) With each fader carrying a different loop, the mixing desk acted like a synthesizer, and we played it like a musical instrument, too, carefully overdubbing textures to the prerecorded backing track. Finally we completed the task to the band’s satisfaction, the white-coated technicians were freed from their labors, and (the) loops were retured back to the plastic bag, never to be played again."

George Martin elaborates yet further: "We fed the sounds down from those tape machines into the faders so they were constant. All you had to do to listen to them was raise a fader - so it was like an organ really. Then by running the four-track machine with the drums and voice (tracks one and four respectively), you could combine those effects wherever you wanted them. I got everybody doing this; the boys bringing the faders in and out. Geoff Emerick masterminded it." George Martin elaborates yet further: "We fed the sounds down from those tape machines into the faders so they were constant. All you had to do to listen to them was raise a fader - so it was like an organ really. Then by running the four-track machine with the drums and voice (tracks one and four respectively), you could combine those effects wherever you wanted them. I got everybody doing this; the boys bringing the faders in and out. Geoff Emerick masterminded it."

This being only his second day as The Beatles' primary engineer, 20 year old Geoff Emerick was astounded by what an imaginative and unexpected role he was asked to oversee. "We had no sense of the momentousness of what we were doing," Geoff Emerick recalls in his book "Here, There And Everywhere." "It all just seemed like a bit of fun in a good cause at the time - but what we created that afternoon was actually the forerunner of today's beat-and-loop-driven music." The mix of these tape loops were all recorded as an overdub onto track two of the four-track tape, effort being made not to overstep the spaces allotted for John's lead vocal lines. This being only his second day as The Beatles' primary engineer, 20 year old Geoff Emerick was astounded by what an imaginative and unexpected role he was asked to oversee. "We had no sense of the momentousness of what we were doing," Geoff Emerick recalls in his book "Here, There And Everywhere." "It all just seemed like a bit of fun in a good cause at the time - but what we created that afternoon was actually the forerunner of today's beat-and-loop-driven music." The mix of these tape loops were all recorded as an overdub onto track two of the four-track tape, effort being made not to overstep the spaces allotted for John's lead vocal lines.

Although John didn’t get his chanting monks, he did get something else he wanted on this day. “We were always asking George Martin, ‘Please give us double tracking without having to track it – save time,’” recalls Lennon. “And then one of the engineers who was working with us came in the next day with this machine. We’d got ADT – and that was beautiful.” Ken Townsend was that maintenance engineer, who then later explained: “They often liked to double-track their vocals but it’s quite a laborious process and they soon got fed up with it. So after one particularly trying night-time session doing just that, I was driving home and I suddenly had an idea…” Although John didn’t get his chanting monks, he did get something else he wanted on this day. “We were always asking George Martin, ‘Please give us double tracking without having to track it – save time,’” recalls Lennon. “And then one of the engineers who was working with us came in the next day with this machine. We’d got ADT – and that was beautiful.” Ken Townsend was that maintenance engineer, who then later explained: “They often liked to double-track their vocals but it’s quite a laborious process and they soon got fed up with it. So after one particularly trying night-time session doing just that, I was driving home and I suddenly had an idea…”

His idea was “Artificial Double Tracking” (or ADT for short). Mark Lewisohn's 1987 book “The Beatles Recording Sessions” explains: “ADT is a process whereby a recording signal is taken from the playback head of a tape machine, is recorded onto a separate machine which has a variable oscillator (enabling the speed to be altered) and then fed back into the first machine to be combined with the original signal…One voice laid perfectly on top of another produces one image. But move the second voice by just a few milli-seconds and two separate images emerge.” Almost all of the tracks on “Revolver” utilized ADT, “Tomorrow Never Knows” being one of them. John’s conventionally recorded vocal in the first half of the song, as recorded the previous day, had ADT applied to it, this being the first time it was used in recording history. His idea was “Artificial Double Tracking” (or ADT for short). Mark Lewisohn's 1987 book “The Beatles Recording Sessions” explains: “ADT is a process whereby a recording signal is taken from the playback head of a tape machine, is recorded onto a separate machine which has a variable oscillator (enabling the speed to be altered) and then fed back into the first machine to be combined with the original signal…One voice laid perfectly on top of another produces one image. But move the second voice by just a few milli-seconds and two separate images emerge.” Almost all of the tracks on “Revolver” utilized ADT, “Tomorrow Never Knows” being one of them. John’s conventionally recorded vocal in the first half of the song, as recorded the previous day, had ADT applied to it, this being the first time it was used in recording history.

With all of the sound effect loops now being in place, this session ended at 7:15 pm, the group then taking an hour break and then reconvening to begin recording a brand new song, this being "Got To Get You Into My Life," leaving off finishing "Tomorrow Never Knows" for another day. With all of the sound effect loops now being in place, this session ended at 7:15 pm, the group then taking an hour break and then reconvening to begin recording a brand new song, this being "Got To Get You Into My Life," leaving off finishing "Tomorrow Never Knows" for another day.

The group decided to finalize "Tomorrow Never Knows" (or "Mark I" as it was still titled at this time) on April 22nd, 1966 in EMI Studio Two, the session beginning with work on George's song "Taxman" at 2:30 pm. They resumed work on "Mark I" at approximately 4:30 pm, the first order of business being to replace John's vocal (and George's tambourine) on track four with one more suitable for the finished recording. In this case, John performed his lead vocal again with ADT and through a rotation Leslie speaker for the final verse, but along with another George Harrison element on the same track instead of his tambourine as before. The group decided to finalize "Tomorrow Never Knows" (or "Mark I" as it was still titled at this time) on April 22nd, 1966 in EMI Studio Two, the session beginning with work on George's song "Taxman" at 2:30 pm. They resumed work on "Mark I" at approximately 4:30 pm, the first order of business being to replace John's vocal (and George's tambourine) on track four with one more suitable for the finished recording. In this case, John performed his lead vocal again with ADT and through a rotation Leslie speaker for the final verse, but along with another George Harrison element on the same track instead of his tambourine as before.

“George Harrison showed up with the tamboura he had so eagerly talked of during the first night’s session,” recalls Geoff Emerick. “Actually, he’d been talking about it almost nonstop since then, so everyone was really curious to see the thing. He staggered into the studio under its weight, it’s a huge instrument and the case was the size of a small coffin, and brought it out with a grand gesture, displaying it proudly as we gathered around.” “George Harrison showed up with the tamboura he had so eagerly talked of during the first night’s session,” recalls Geoff Emerick. “Actually, he’d been talking about it almost nonstop since then, so everyone was really curious to see the thing. He staggered into the studio under its weight, it’s a huge instrument and the case was the size of a small coffin, and brought it out with a grand gesture, displaying it proudly as we gathered around.”

"'What do you think to that, then' he asked everyone in sight. Not willing to trust his precious cargo to either of the two roadies, he had actually stuffed the tamboura case in the backseat of one of his Porsches, which he parked right in front of the main entrance so he could carry the instrument by hand up the steps…Having seen how well Paul’s loops had worked, George wanted to contribute one of his own, so I recorded him playing a single note on the huge instrument – again using a close-miking technique – and turned it into a loop. It ended up becoming the sound that opens the track." This tape loop, which was apparently prepared on another four-track machine, was then recorded onto track four of the main tape while Lennon sang the above-mentioned new lead vocal onto the same track. "'What do you think to that, then' he asked everyone in sight. Not willing to trust his precious cargo to either of the two roadies, he had actually stuffed the tamboura case in the backseat of one of his Porsches, which he parked right in front of the main entrance so he could carry the instrument by hand up the steps…Having seen how well Paul’s loops had worked, George wanted to contribute one of his own, so I recorded him playing a single note on the huge instrument – again using a close-miking technique – and turned it into a loop. It ended up becoming the sound that opens the track." This tape loop, which was apparently prepared on another four-track machine, was then recorded onto track four of the main tape while Lennon sang the above-mentioned new lead vocal onto the same track.

This left only track three available on the original four-track tape, John taking it upon himself to double-track his lead vocals on this track along with Ringo overdubbing a tambourine performance superior to what Harrison had performed two weeks earlier. Interestingly, simultaneous to double-tracking his vocals, Lennon recorded organ in strategic places of the song. George Harrison explains the purpose of the organ overdub: “Indian music doesn’t modulate, it just stays. You pick what key you’re in, and it stays in that key. I think ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ was the first one that stayed there, the whole song was on one chord. But there is a chord that is superimposed on top that does change: if it was in C, it changes down to B flat. That was like an overdub, but the basic sound all hangs on the one drone.” This left only track three available on the original four-track tape, John taking it upon himself to double-track his lead vocals on this track along with Ringo overdubbing a tambourine performance superior to what Harrison had performed two weeks earlier. Interestingly, simultaneous to double-tracking his vocals, Lennon recorded organ in strategic places of the song. George Harrison explains the purpose of the organ overdub: “Indian music doesn’t modulate, it just stays. You pick what key you’re in, and it stays in that key. I think ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ was the first one that stayed there, the whole song was on one chord. But there is a chord that is superimposed on top that does change: if it was in C, it changes down to B flat. That was like an overdub, but the basic sound all hangs on the one drone.”

The overdubbed organ plays this B flat chord in the fifth and sixth measures of most verses (for instance, during the lyrics “It is not dyinnnng…”) and then it plays a C chord during the seventh and (sometimes) eighth measures to return to the droning home key of the song. This organ is added to the dissonant wail of the “orchestral chord” loop that also appears during the sixth and seventh measure of most verses. The simultaneous coupling of these two distinct elements produces the desired effect, something similar also being added to George’s song “Love You To” a few days later. The overdubbed organ plays this B flat chord in the fifth and sixth measures of most verses (for instance, during the lyrics “It is not dyinnnng…”) and then it plays a C chord during the seventh and (sometimes) eighth measures to return to the droning home key of the song. This organ is added to the dissonant wail of the “orchestral chord” loop that also appears during the sixth and seventh measure of most verses. The simultaneous coupling of these two distinct elements produces the desired effect, something similar also being added to George’s song “Love You To” a few days later.

Another overdub was also recorded onto track three of the four-track tape on this day. During the open spaces left in the instrumental section of the song, which only contained the sound-effect tape loops at this point, a decision was made to spruce up this section with a little backwards guitar played by George Harrison. The book “Revolution In The Head” claims that this element was actually "parts of McCartney’s guitar solo for ‘Taxman’ slowed down a tone, cut up, and run backwards, reversed and transposed down to C." However, when listened to carefully, along with verification from the 2022 Deluxe editions of "Revolver," this has been found to be false, George Harrison actually recording a new lead guitar section that begins with feedback that is heard in the released stereo mix at the beginning of the final verse during the lyric "that love is all, that love is everyone." Another overdub was also recorded onto track three of the four-track tape on this day. During the open spaces left in the instrumental section of the song, which only contained the sound-effect tape loops at this point, a decision was made to spruce up this section with a little backwards guitar played by George Harrison. The book “Revolution In The Head” claims that this element was actually "parts of McCartney’s guitar solo for ‘Taxman’ slowed down a tone, cut up, and run backwards, reversed and transposed down to C." However, when listened to carefully, along with verification from the 2022 Deluxe editions of "Revolver," this has been found to be false, George Harrison actually recording a new lead guitar section that begins with feedback that is heard in the released stereo mix at the beginning of the final verse during the lyric "that love is all, that love is everyone."

There was one final touch added to complete the song, this being tacked onto the end of track three of the four-track tape. “Another sonic component,” Geoff Emerick explains, “the little bit of tack piano at the end was a fluke. It actually came from a trial we did on the first take, when the group were just putting ideas down, but Paul heard it during one of the playbacks and suggested that we fly it into the fadeout, and it worked perfectly.” Paul's suggestion was completed by 11:30 pm and the song was deemed acceptable to all and was destined for mixing in the near future. There was one final touch added to complete the song, this being tacked onto the end of track three of the four-track tape. “Another sonic component,” Geoff Emerick explains, “the little bit of tack piano at the end was a fluke. It actually came from a trial we did on the first take, when the group were just putting ideas down, but Paul heard it during one of the playbacks and suggested that we fly it into the fadeout, and it worked perfectly.” Paul's suggestion was completed by 11:30 pm and the song was deemed acceptable to all and was destined for mixing in the near future.