Search by Keyword

Sign Up Below for our MONTHLY BEATLES TRIVIA QUIZ!

|

“WITHIN YOU WITHOUT YOU”

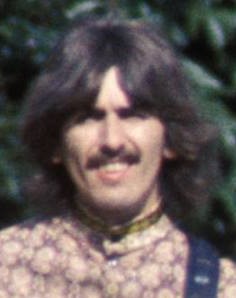

(George Harrison)

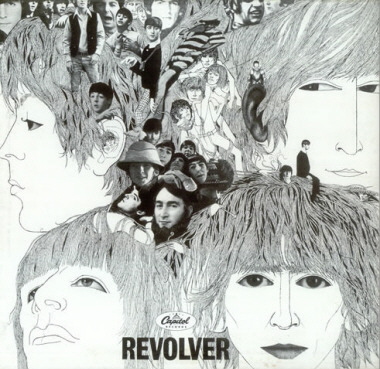

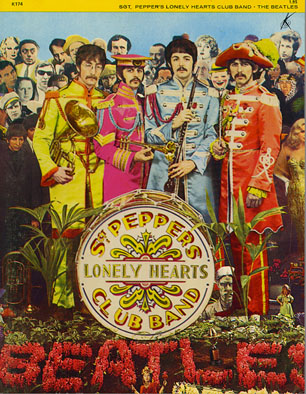

Having secured three coveted songwriting positions on their previous album “Revolver,” George Harrison was poised to provide at least one contribution to The Beatles landmark 1967 album “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” The only problem appeared to be that he just wasn't up for the task. Having secured three coveted songwriting positions on their previous album “Revolver,” George Harrison was poised to provide at least one contribution to The Beatles landmark 1967 album “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” The only problem appeared to be that he just wasn't up for the task.

“I went to India in September, 1966,” stated Harrison. “It was becoming difficult for me, because I wasn’t really that into it…I’d just got back from India, and my heart was still out there. After what had happened in 1966, everything else seemed like hard work. It was a job, like doing something I didn’t really want to do, and I was losing interest in being ‘fab’ at that point.”

Two-and-a-half months into the recording of the album, George did muster up a song as his contribution to “Sgt. Pepper.” “Only A Northern Song” was then partially recorded with some halfhearted cooperation from both Ringo and Paul, but the overall consensus was that this composition was not even close to the caliber of the rest of the album, a collection that they already knew would be a milestone of their career. The lyrics bemoaned the opinion that “it doesn’t really matter what chords I play, what words I say…because it’s only a Northern Song.” “Northern Songs” was the name of the publishing company that George was a contracted songwriter for, but the lyrics may also be a sly reference to how his focus was more in an Eastern direction at that point as opposed to Northern. Two-and-a-half months into the recording of the album, George did muster up a song as his contribution to “Sgt. Pepper.” “Only A Northern Song” was then partially recorded with some halfhearted cooperation from both Ringo and Paul, but the overall consensus was that this composition was not even close to the caliber of the rest of the album, a collection that they already knew would be a milestone of their career. The lyrics bemoaned the opinion that “it doesn’t really matter what chords I play, what words I say…because it’s only a Northern Song.” “Northern Songs” was the name of the publishing company that George was a contracted songwriter for, but the lyrics may also be a sly reference to how his focus was more in an Eastern direction at that point as opposed to Northern.

“Before then everything I’d known had been in the West, and so the trips to India had really opened me up. I was into the whole thing, the music, the culture, the smells. I’d been let out of the confines of the group, and it was hard for me to come back into the sessions. In a way, it felt like going backwards. Everybody else thought that 'Sgt. Pepper' was a revolutionary record – but for me it was not that enjoyable…I was growing out of that kind of thing.” “Before then everything I’d known had been in the West, and so the trips to India had really opened me up. I was into the whole thing, the music, the culture, the smells. I’d been let out of the confines of the group, and it was hard for me to come back into the sessions. In a way, it felt like going backwards. Everybody else thought that 'Sgt. Pepper' was a revolutionary record – but for me it was not that enjoyable…I was growing out of that kind of thing.”

A month later, to everyone’s relief, Harrison popped in to the sessions with another song that fit in perfectly with where his enthusiasm was right then. This composition fit in perfectly with the kaleidoscope of musical genres on display within this album, depicting a euphoric atmosphere amazingly well suited to the “summer of love” mentality that year. The song was titled "Within You Without You." A month later, to everyone’s relief, Harrison popped in to the sessions with another song that fit in perfectly with where his enthusiasm was right then. This composition fit in perfectly with the kaleidoscope of musical genres on display within this album, depicting a euphoric atmosphere amazingly well suited to the “summer of love” mentality that year. The song was titled "Within You Without You."

But was the song accepted by the rest of the group? But was the song accepted by the rest of the group?

John Lennon in Playboy (1981): “I think that is one of George’s best songs, one of my favorites of his. I like the arrangement, the sound and the words. He is clear on that song. You can hear that his mind is clear and his music is clear. It’s his innate talent that comes through on the song, that brought that song together. George is responsible for Indian music getting over here. That song is a very good example.”

Ringo Starr: “’Within You Without You’ is brilliant. I Love It!”

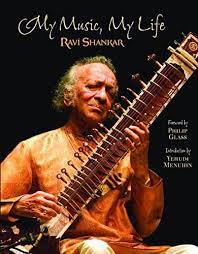

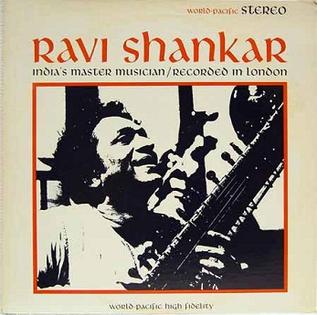

Songwriting History

Explaining the origins of “Within You Without You” simply can't be accomplished without first describing the profound effect that the introduction to Eastern religion had on George Harrison. Under the name of Sam Wells, George and his wife Pattie, vacationed in Bombay, India for an entire six weeks, beginning on September 20th, 1966. At the suggestion of popular sitarist Ravi Shankar, from whom he was going to take sitar lessons while in Bombay, Harrison grew a mustache as a subtle disguise so as to ward off Indian "Beatlemaniacs" that could have been present. "I had George practice all of the correct positions of sitting and some basic exercises," the late Ravi Shankar wrote in his 1969 autobiography, "My Music, My Life." "This was the most anybody could do in six weeks, considering that a disciple usually spends years learning these basics." Explaining the origins of “Within You Without You” simply can't be accomplished without first describing the profound effect that the introduction to Eastern religion had on George Harrison. Under the name of Sam Wells, George and his wife Pattie, vacationed in Bombay, India for an entire six weeks, beginning on September 20th, 1966. At the suggestion of popular sitarist Ravi Shankar, from whom he was going to take sitar lessons while in Bombay, Harrison grew a mustache as a subtle disguise so as to ward off Indian "Beatlemaniacs" that could have been present. "I had George practice all of the correct positions of sitting and some basic exercises," the late Ravi Shankar wrote in his 1969 autobiography, "My Music, My Life." "This was the most anybody could do in six weeks, considering that a disciple usually spends years learning these basics."

While there, George became very enamored with the culture and, especially, the religion. “I believe much more in the religions of India than in anything I ever learned from Christianity,” he was quoted as saying during a BBC interview on the very day he arrived in Bombay, India. “The difference over here is that their religion is every second and every minute of their lives and it is them, how they act and how they conduct themselves and how they think.” In May of 1967, Harrison elaborated further: “I’ve taken the time to learn about the many religions. Religion is a day-to-day experience. You find it all around. You live it. Religion is here and now. Not just something that just comes on Sundays!” While there, George became very enamored with the culture and, especially, the religion. “I believe much more in the religions of India than in anything I ever learned from Christianity,” he was quoted as saying during a BBC interview on the very day he arrived in Bombay, India. “The difference over here is that their religion is every second and every minute of their lives and it is them, how they act and how they conduct themselves and how they think.” In May of 1967, Harrison elaborated further: “I’ve taken the time to learn about the many religions. Religion is a day-to-day experience. You find it all around. You live it. Religion is here and now. Not just something that just comes on Sundays!”

George, in the book “Beatles Anthology,” goes into even further detail by recounting: “For me, travelling to India and reading somebody stating, ‘No, you can not believe anything until you have direct perception of it,’ which was obvious, really, made me think, ‘Wow! Fantastic! At last I’ve found somebody who makes some sense.’ So I wanted to go deeper and deeper into that. That’s how it affected me. I read into books by various holy men and swamis and mystics and then went around and looked for them and tried to meet some.” George, in the book “Beatles Anthology,” goes into even further detail by recounting: “For me, travelling to India and reading somebody stating, ‘No, you can not believe anything until you have direct perception of it,’ which was obvious, really, made me think, ‘Wow! Fantastic! At last I’ve found somebody who makes some sense.’ So I wanted to go deeper and deeper into that. That’s how it affected me. I read into books by various holy men and swamis and mystics and then went around and looked for them and tried to meet some.”

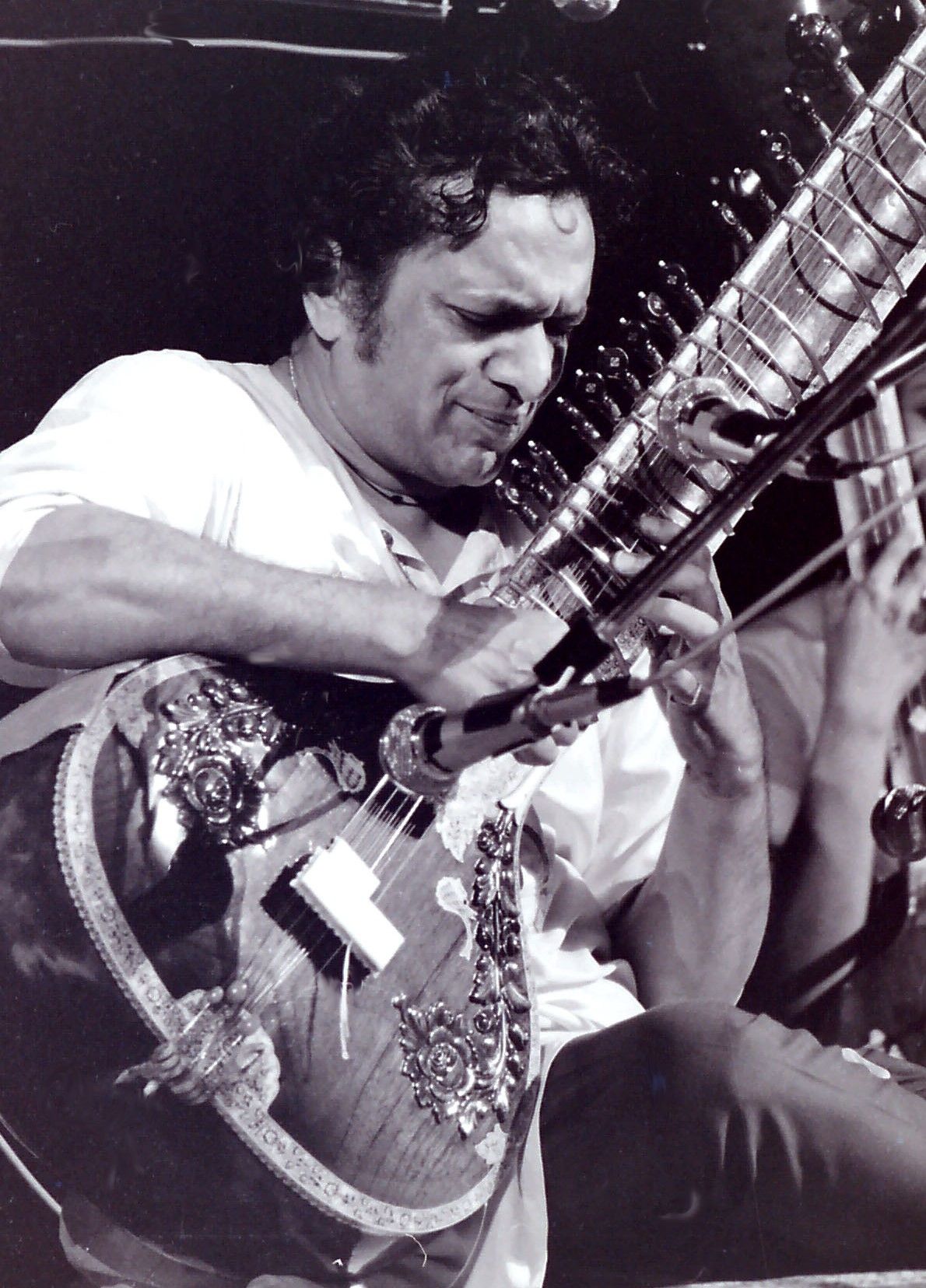

As quoted in Andy Babiuk’s book “Beatles Gear,” Ravi Shankar speaks of Harrison’s “tremendous interest in Indian philosophy, religion and so on. It was so strong. I gave him a very famous book, ‘Autobiography Of A Yogi.’ That really altered his whole life and mind. That influenced his writing of beautiful songs like ‘Within You Without You’ and many others.” As quoted in Andy Babiuk’s book “Beatles Gear,” Ravi Shankar speaks of Harrison’s “tremendous interest in Indian philosophy, religion and so on. It was so strong. I gave him a very famous book, ‘Autobiography Of A Yogi.’ That really altered his whole life and mind. That influenced his writing of beautiful songs like ‘Within You Without You’ and many others.”

George’s research led to his firm belief that “we’re all one” – this meaning that all creation, including our individual selves, are made of the same energy field (or life force) and are therefore all invisibly connected to each other. Most of general mankind view themselves as individual beings and, thereby, separate from everyone and everything else – this referred to by various mystics and teachers as the “ego.” Not realizing their inter-connectedness, they thereby in essence “hide themselves behind a wall of illusion.” Obtaining this true realization during their lifetime is the ultimate goal because “it’s far too late when they pass away.” The more people that would realize the power that they do possess, the more they could harness this collective energy through various means, such as through meditation, to spread love throughout the world. As George sings, “With our love we could save the world – if they only knew.” George’s research led to his firm belief that “we’re all one” – this meaning that all creation, including our individual selves, are made of the same energy field (or life force) and are therefore all invisibly connected to each other. Most of general mankind view themselves as individual beings and, thereby, separate from everyone and everything else – this referred to by various mystics and teachers as the “ego.” Not realizing their inter-connectedness, they thereby in essence “hide themselves behind a wall of illusion.” Obtaining this true realization during their lifetime is the ultimate goal because “it’s far too late when they pass away.” The more people that would realize the power that they do possess, the more they could harness this collective energy through various means, such as through meditation, to spread love throughout the world. As George sings, “With our love we could save the world – if they only knew.”

Regarding the new beliefs that he specifically wrote about in the song, George remembered: “There are so many people who don’t understand the sentiments of ‘Within You Without You.’ They can not see outside of themselves. They are too self-important and can not see how small we all are. We’re all one. The realization of human love reciprocated is such a gas. It is a good vibration which makes you feel good. These vibrations that you acheive through yoga, cosmic chants and things like that. It has nothing to do with pills. It is just in your own head, the realization. It is such a buzz. It buzzes you right into the astral plane.” Regarding the new beliefs that he specifically wrote about in the song, George remembered: “There are so many people who don’t understand the sentiments of ‘Within You Without You.’ They can not see outside of themselves. They are too self-important and can not see how small we all are. We’re all one. The realization of human love reciprocated is such a gas. It is a good vibration which makes you feel good. These vibrations that you acheive through yoga, cosmic chants and things like that. It has nothing to do with pills. It is just in your own head, the realization. It is such a buzz. It buzzes you right into the astral plane.”

Sometime after his return from India, most likely around early March of 1967, George and Pattie were invited to a dinner party at the Hampstead, London residence of close friend Klaus Voormann. Tony King, who had known The Beatles since 1963 and would work with them at Apple Corps shortly afterwards, was also present at this party. Describing the atmosphere at this event in Steve Turner’s book “A Hard Day’s Write,” Tony King remembers: “We were all on about the 'wall of illusion' and about the love that flowed between us but none of us knew what we were talking about. We all developed these groovy voices. It was a bit ridiculous really. It was as if we all were sages all of a sudden. We all felt as if we had glimpsed the meaning of the universe.” Sometime after his return from India, most likely around early March of 1967, George and Pattie were invited to a dinner party at the Hampstead, London residence of close friend Klaus Voormann. Tony King, who had known The Beatles since 1963 and would work with them at Apple Corps shortly afterwards, was also present at this party. Describing the atmosphere at this event in Steve Turner’s book “A Hard Day’s Write,” Tony King remembers: “We were all on about the 'wall of illusion' and about the love that flowed between us but none of us knew what we were talking about. We all developed these groovy voices. It was a bit ridiculous really. It was as if we all were sages all of a sudden. We all felt as if we had glimpsed the meaning of the universe.”

“Klaus (Voormann) had a harmonium in his house, which I hadn't played before,” George remembers about that day as related in Hunter Davies' 1968 biography "The Beatles." George adds: "I was doodling on it, playing to amuse myself, when (the song) ‘Within You’ started to come. The tune came first and then I got the first sentence. It came out of what we'd been doing that evening, 'We were talking.' That's as far as I got that night. I finished the rest of the words later at home. The words are always a bit of a hangup for me. I'm not very poetic so my lyrics are poor, really. But I don't take any of it seriously. It's just a joke. A personal joke. It's great if someone else likes it, but I don't take it too seriously myself.” “Klaus (Voormann) had a harmonium in his house, which I hadn't played before,” George remembers about that day as related in Hunter Davies' 1968 biography "The Beatles." George adds: "I was doodling on it, playing to amuse myself, when (the song) ‘Within You’ started to come. The tune came first and then I got the first sentence. It came out of what we'd been doing that evening, 'We were talking.' That's as far as I got that night. I finished the rest of the words later at home. The words are always a bit of a hangup for me. I'm not very poetic so my lyrics are poor, really. But I don't take any of it seriously. It's just a joke. A personal joke. It's great if someone else likes it, but I don't take it too seriously myself.”

Tony King adds more detail to the event: “Klaus (Voormann) had this pedal harmonium and George went into an adjoining room and starting fiddling around on it. It made these terrible groaning noises and, by the end of the evening, he’d worked something out and was starting to sing snatches of it to us. It’s interesting that the eventual recording of ‘Within You Without You’ had the very same groaning sound that I had heard on the harmonium because Lennon once told me that the instrument that you compose a song on determines the tone of a song.” Tony King adds more detail to the event: “Klaus (Voormann) had this pedal harmonium and George went into an adjoining room and starting fiddling around on it. It made these terrible groaning noises and, by the end of the evening, he’d worked something out and was starting to sing snatches of it to us. It’s interesting that the eventual recording of ‘Within You Without You’ had the very same groaning sound that I had heard on the harmonium because Lennon once told me that the instrument that you compose a song on determines the tone of a song.”

George apparently worked out the remainder of the song when alone at his Kinfauns home in Surrey, England, in the next few days. Regarding the song's melody and structure, Harrison stated that it "was a song that I wrote based on a piece of music of Ravi's that he'd recorded for All-India Radio. It was a very long piece - maybe thirty or forty minutes - and was written in different parts, with a progression in each. I wrote a mini version of it, using sounds quite similar to those I'd discovered in his piece." George apparently worked out the remainder of the song when alone at his Kinfauns home in Surrey, England, in the next few days. Regarding the song's melody and structure, Harrison stated that it "was a song that I wrote based on a piece of music of Ravi's that he'd recorded for All-India Radio. It was a very long piece - maybe thirty or forty minutes - and was written in different parts, with a progression in each. I wrote a mini version of it, using sounds quite similar to those I'd discovered in his piece."

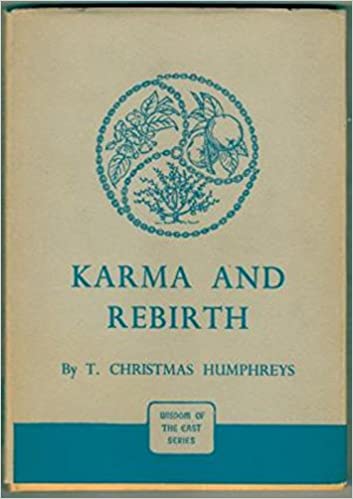

In regards to the song's title, Pattie's sister Jenny Boyd, in her 2020 book "Jennifer Juniper," remembers: "I picked up a book called 'Karma And Rebirth' by author Christmas Humphries. I began reading it until I came across a passage that said, 'Life goes on within you and without you.' I read it again and then again, marveling at the double meaning. It was so clever and so true. My first inclination was to call up Pattie and George. George answered the phone. 'Listen to this,' I insisted, and then I repeated the sentence. It inspired him to compose 'Within You Without You,' which he later recorded for The Beatles." In regards to the song's title, Pattie's sister Jenny Boyd, in her 2020 book "Jennifer Juniper," remembers: "I picked up a book called 'Karma And Rebirth' by author Christmas Humphries. I began reading it until I came across a passage that said, 'Life goes on within you and without you.' I read it again and then again, marveling at the double meaning. It was so clever and so true. My first inclination was to call up Pattie and George. George answered the phone. 'Listen to this,' I insisted, and then I repeated the sentence. It inspired him to compose 'Within You Without You,' which he later recorded for The Beatles."

Recording History

March 15th, 1967 was the first recording session to focus attention on George's recently written song “Within You Without You,” although, as usual, he had not decided on the song’s title as of this day, the tape box identifying the track as “Untitled.” Engineer Geoff Emerick, in his book “Here, There And Everywhere,” relates the experience of getting acquainted with the song: “After the debacle of ‘Only A Northern Song,’ nobody was really expecting too much of George Harrison, and, quite frankly, when he came in at around this time and previewed ‘Within You Without You’ for us, nobody was overwhelmed. Personally, I thought it was just tedious. Of course, just hearing him run it down on acoustic guitar presented very little idea of the beautiful song that it was to turn into once all the overdubs were completed, but at that time it caused a lot of eye-rolling among the other Beatles and George Martin.” March 15th, 1967 was the first recording session to focus attention on George's recently written song “Within You Without You,” although, as usual, he had not decided on the song’s title as of this day, the tape box identifying the track as “Untitled.” Engineer Geoff Emerick, in his book “Here, There And Everywhere,” relates the experience of getting acquainted with the song: “After the debacle of ‘Only A Northern Song,’ nobody was really expecting too much of George Harrison, and, quite frankly, when he came in at around this time and previewed ‘Within You Without You’ for us, nobody was overwhelmed. Personally, I thought it was just tedious. Of course, just hearing him run it down on acoustic guitar presented very little idea of the beautiful song that it was to turn into once all the overdubs were completed, but at that time it caused a lot of eye-rolling among the other Beatles and George Martin.”

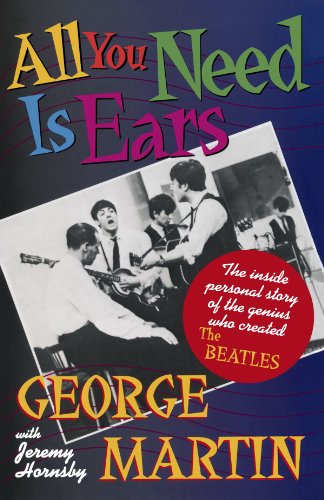

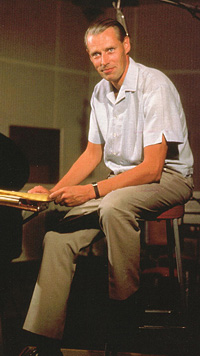

The session, scheduled as usual to begin at 7 pm, took place in EMI Studio Two and was attended by some special guests. “He brought in friends from the Indian Music Association to play some special instruments,” George Martin explains in his book “All You Need Is Ears.” Mark Lewisohn’s book “The Beatles Recording Sessions” describes the Indian musicians as coming “from the Asian Music Circle in Fitzalan Road, Finchley, north London.” “There are some Indian musicians who worked on ‘Pepper’ who still have not been paid simply because George does not know their names,” George Martin stated in interview shortly after the release of the album. The session, scheduled as usual to begin at 7 pm, took place in EMI Studio Two and was attended by some special guests. “He brought in friends from the Indian Music Association to play some special instruments,” George Martin explains in his book “All You Need Is Ears.” Mark Lewisohn’s book “The Beatles Recording Sessions” describes the Indian musicians as coming “from the Asian Music Circle in Fitzalan Road, Finchley, north London.” “There are some Indian musicians who worked on ‘Pepper’ who still have not been paid simply because George does not know their names,” George Martin stated in interview shortly after the release of the album.

Hunter Davies, in his "The Beatles" biography, explains that "George has great difficulty getting the right sort of trained Indian musicians for studio sessions in London. For 'Within You Without You'...he spent weeks finding and auditioning musicians who play Indian instruments. There were no full-time professionals in England playing the instruments he wanted." Hunter Davies, in his "The Beatles" biography, explains that "George has great difficulty getting the right sort of trained Indian musicians for studio sessions in London. For 'Within You Without You'...he spent weeks finding and auditioning musicians who play Indian instruments. There were no full-time professionals in England playing the instruments he wanted."

"They have jobs like bus driving during the day and only perform in the evening," Harrison explained, "so some of them just weren't good enough, but we still had to use them. They were much better than any Western musician could do, because this at least was their natural style, but this made things very difficult. We spent hours just rehearsing and rehearsing."

Since Harrison was “a detached, reluctant participant” during the recording of a good portion of the "Sgt Pepper" album, as Geoff Emerick described him, “George Martin must have known that he felt that way, which would explain why he was prepared to put so much time and effort into recording this song. My theory was that, while George Harrison may well have felt trapped by The Beatles' fame and notoriety, he did not want to let the side down, either. That’s why there was such a sense of relief among everyone when the track turned out so well.” Since Harrison was “a detached, reluctant participant” during the recording of a good portion of the "Sgt Pepper" album, as Geoff Emerick described him, “George Martin must have known that he felt that way, which would explain why he was prepared to put so much time and effort into recording this song. My theory was that, while George Harrison may well have felt trapped by The Beatles' fame and notoriety, he did not want to let the side down, either. That’s why there was such a sense of relief among everyone when the track turned out so well.”

"Studio Two had a hardwood floor, so in order to dampen the sound, I normally put down carpeting underneath Ringo’s drums and in the area where Beatles vocals were recorded," continued Geoff Emerick. "But this time Richard and I got out a bunch of throwrugs and spread them all around the floor for the musicians to sit on, all in an effort to make them more comfortable and to make the studio a bit more homey. Mind you, the Abbey Road throwrugs were completely moth-eaten and dilapidated…but it was the thought that counted." "Studio Two had a hardwood floor, so in order to dampen the sound, I normally put down carpeting underneath Ringo’s drums and in the area where Beatles vocals were recorded," continued Geoff Emerick. "But this time Richard and I got out a bunch of throwrugs and spread them all around the floor for the musicians to sit on, all in an effort to make them more comfortable and to make the studio a bit more homey. Mind you, the Abbey Road throwrugs were completely moth-eaten and dilapidated…but it was the thought that counted."

Geoff Emerick also adds: “All four Beatles were there when the basic track was recorded, along with famed illustrator Peter Blake, who was there to talk about the ‘Sgt. Pepper’ album cover. He mostly huddled with Paul and John while George was busy instructing the musicians as to the parts he wanted them to play. Ringo, as usual, was lost in a game of chess off in a corner with Neil (Aspinall).” Geoff Emerick also adds: “All four Beatles were there when the basic track was recorded, along with famed illustrator Peter Blake, who was there to talk about the ‘Sgt. Pepper’ album cover. He mostly huddled with Paul and John while George was busy instructing the musicians as to the parts he wanted them to play. Ringo, as usual, was lost in a game of chess off in a corner with Neil (Aspinall).”

Regarding the atmosphere in the recording studio during the above mentioned rehearsals for “Within You Without You,” artist Peter Blake remembered: “George was there with some Indian musicians and they had a carpet on the floor and there was incense burning. George was very sweet - he has always been very kind and sweet - and he got up and welcomed us in and offered us tea. We just sat and watched them for a couple of hours. It was a fascinating, historical time.” Geoff Emerick agrees: “It was very calm and peaceful in the studio that evening. Harrison was surrounded by his new friends, the Indian Musicians, and he was gracious and welcoming when Peter Blake arrived; for perhaps the first time during the ‘Sgt Pepper’ sessions, I could see that George was completely relaxed." Regarding the atmosphere in the recording studio during the above mentioned rehearsals for “Within You Without You,” artist Peter Blake remembered: “George was there with some Indian musicians and they had a carpet on the floor and there was incense burning. George was very sweet - he has always been very kind and sweet - and he got up and welcomed us in and offered us tea. We just sat and watched them for a couple of hours. It was a fascinating, historical time.” Geoff Emerick agrees: “It was very calm and peaceful in the studio that evening. Harrison was surrounded by his new friends, the Indian Musicians, and he was gracious and welcoming when Peter Blake arrived; for perhaps the first time during the ‘Sgt Pepper’ sessions, I could see that George was completely relaxed."

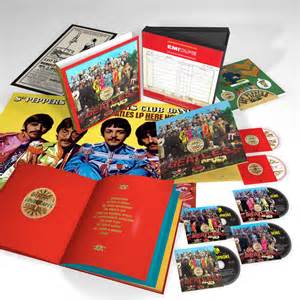

As featured on a bonus track in the 50th Anniversary Edition of "Sgt. Pepper," Harrison takes a relaxed but concerted effort in going through the arrangement of his song with the musicians, directing them verbally as to how the melody line should be performed. Harrison taught himself to write down his music in Indian script so that the Indian musicians could play them easily. As featured on a bonus track in the 50th Anniversary Edition of "Sgt. Pepper," Harrison takes a relaxed but concerted effort in going through the arrangement of his song with the musicians, directing them verbally as to how the melody line should be performed. Harrison taught himself to write down his music in Indian script so that the Indian musicians could play them easily.

"Instead of quavers and dots written across lines," George explains in Hunter Davies' 1968 biography "The Beatles," "Indian music is written down very simply like our tonic sol-fa. Instead of Do, Re, Mi, and so on, they sing Sa, Re, Ga, Ma, Pa, Dha, Ni, Sa. Often they don't have words for songs, but just sing those notes. You indicate how high or low, or how long each one is, by putting little marks under each note. The first notes of 'Within You' to go with the words 'We were talking' would go Ga, Ma, Pa, Ni. You just need to write the first letter; that's enough. Now I can go to the Indian musicians, give them the music and play it through to let them all listen to it, and they can do it themselves." As caught on tape during these rehearsals, George verbally goes through "Within You Without You" in this way and then directs proceedings by saying, "Ok, should we try it from the beginning?," adding instructions to Geoff Emerick, "Just tape it, Geoff, just in case." "Instead of quavers and dots written across lines," George explains in Hunter Davies' 1968 biography "The Beatles," "Indian music is written down very simply like our tonic sol-fa. Instead of Do, Re, Mi, and so on, they sing Sa, Re, Ga, Ma, Pa, Dha, Ni, Sa. Often they don't have words for songs, but just sing those notes. You indicate how high or low, or how long each one is, by putting little marks under each note. The first notes of 'Within You' to go with the words 'We were talking' would go Ga, Ma, Pa, Ni. You just need to write the first letter; that's enough. Now I can go to the Indian musicians, give them the music and play it through to let them all listen to it, and they can do it themselves." As caught on tape during these rehearsals, George verbally goes through "Within You Without You" in this way and then directs proceedings by saying, "Ok, should we try it from the beginning?," adding instructions to Geoff Emerick, "Just tape it, Geoff, just in case."

As to McCartney and Lennon’s activities during these rehearsals, Geoff Emerick continues: “Paul was somewhat interested in the goings-on and in how the various Indian instruments were played - eventually he even bought a sitar himself - but Lennon seemed quite bored, wandering around the studio aimlessly, not knowing what to contribute.” “George has done a great Indian one,” stated McCartney in 1967. “We all came along one night and he had about 400 Indian fellas playing there, and it was a great swinging evening, as they say.” As to McCartney and Lennon’s activities during these rehearsals, Geoff Emerick continues: “Paul was somewhat interested in the goings-on and in how the various Indian instruments were played - eventually he even bought a sitar himself - but Lennon seemed quite bored, wandering around the studio aimlessly, not knowing what to contribute.” “George has done a great Indian one,” stated McCartney in 1967. “We all came along one night and he had about 400 Indian fellas playing there, and it was a great swinging evening, as they say.”

Geoff Emerick adds: "As the other instruments began to be layered on top of the drone, the structure of the song started to make a little more sense. I quite liked the sound of the tabla, and, as I had done on George’s ‘Revolver’ track ‘Love You To,’ I once again decided to close-mic them and add signal processing to make things a bit more exciting sonically." After the arrangement was worked out and all the instrumentalists were warmed up, it was then time for the tapes to roll. “Eventually the recording commenced,” remembered Geoff Emerick. “It was decided to first lay down a drone, with three of the four musicians playing one note continuously; even Neil Aspinall was recruited to assist Harrison in playing tamboura. Geoff Emerick adds: "As the other instruments began to be layered on top of the drone, the structure of the song started to make a little more sense. I quite liked the sound of the tabla, and, as I had done on George’s ‘Revolver’ track ‘Love You To,’ I once again decided to close-mic them and add signal processing to make things a bit more exciting sonically." After the arrangement was worked out and all the instrumentalists were warmed up, it was then time for the tapes to roll. “Eventually the recording commenced,” remembered Geoff Emerick. “It was decided to first lay down a drone, with three of the four musicians playing one note continuously; even Neil Aspinall was recruited to assist Harrison in playing tamboura.

In Mark Lewisohn's 1988 “The Beatles Recording Sessions” book, Geoff Emerick states: “Everyone was amazed when they first heard a tabla recorded that close and with the texture and the lovely low resonances.” Other Indian instruments recorded on this day were surmandal, a multi-stringed board zither, and a dilruba, this being described by Geoff Emerick as “a bowed instrument similar to a sitar, but smaller." In Mark Lewisohn's 1988 “The Beatles Recording Sessions” book, Geoff Emerick states: “Everyone was amazed when they first heard a tabla recorded that close and with the texture and the lovely low resonances.” Other Indian instruments recorded on this day were surmandal, a multi-stringed board zither, and a dilruba, this being described by Geoff Emerick as “a bowed instrument similar to a sitar, but smaller."

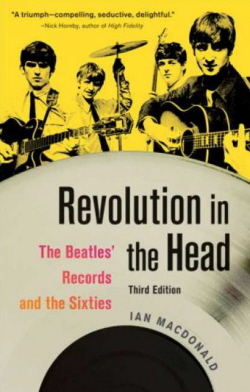

Using the above-mentioned Ravi Shankar composition as inspiration, the recording was done in three sections: the first comprising the first two verses and the refrain, the second being the elaborate 5/4 instrumental section of the song, and the third being the return to the original tempo and comprising the final verse and refrain. However, as heard on a bonus track contained on the 2017 released 50th Anniversary Edition of "Sgt. Pepper," both of the slower tempo sections of the song were recorded first, interrupted by George Harrison's direction "Ok, uh just go...," which then evolves into the elaborate 5/4 section afterwards. As explained in the book "Revolution In The Head," these were made “in three edit-sections which he then pieced together,” this piecing being done at the mixing stage. The book “The Beatles Recording Sessions” indicates the song “lasting 6:25” at this point, meaning that since the finished product was 5:03, editing had to be done during the mixing stage. Using the above-mentioned Ravi Shankar composition as inspiration, the recording was done in three sections: the first comprising the first two verses and the refrain, the second being the elaborate 5/4 instrumental section of the song, and the third being the return to the original tempo and comprising the final verse and refrain. However, as heard on a bonus track contained on the 2017 released 50th Anniversary Edition of "Sgt. Pepper," both of the slower tempo sections of the song were recorded first, interrupted by George Harrison's direction "Ok, uh just go...," which then evolves into the elaborate 5/4 section afterwards. As explained in the book "Revolution In The Head," these were made “in three edit-sections which he then pieced together,” this piecing being done at the mixing stage. The book “The Beatles Recording Sessions” indicates the song “lasting 6:25” at this point, meaning that since the finished product was 5:03, editing had to be done during the mixing stage.

“Because the song was unusually long,” added Geoff Emerick, “there were quite a few glances between John and Paul when the rhythm track was being recorded, and I could tell that they were a bit dubious. ‘Yes, it’s all very nice,’ I could imagine they were thinking, ‘it’s all very well performed, but it is not Beatles, is it?’ My guess is they went along with it for the sake of group unity.” “Because the song was unusually long,” added Geoff Emerick, “there were quite a few glances between John and Paul when the rhythm track was being recorded, and I could tell that they were a bit dubious. ‘Yes, it’s all very nice,’ I could imagine they were thinking, ‘it’s all very well performed, but it is not Beatles, is it?’ My guess is they went along with it for the sake of group unity.”

“We all knew George liked Indian music,” said George Martin in “The Making Of Sgt. Pepper.” “There was a kind of toleration, if you like, but it was a welcome one, because we actually liked these sounds. The joss sticks were even OK – they covered the smell of pot.” “We all knew George liked Indian music,” said George Martin in “The Making Of Sgt. Pepper.” “There was a kind of toleration, if you like, but it was a welcome one, because we actually liked these sounds. The joss sticks were even OK – they covered the smell of pot.”

All of the Indian instrumentation recorded on this day filled up tracks one, two and four of the four track tape. So, by 1:30 am the following morning, this landmark session was now complete, all of the unnamed Indian musicians going home while the throwrugs were rolled up for the night.

A week later, on March 22nd, 1967, their work continued on “Within You Without You” in EMI Studio Two, this session also earmarked to begin at 7 pm. Geoff Emerick describes the atmosphere in the studio on this day: “A refreshed and rejuvenated George Harrison came back to the studio and oversaw the overdubbing of a couple of additional dilruba parts.” A week later, on March 22nd, 1967, their work continued on “Within You Without You” in EMI Studio Two, this session also earmarked to begin at 7 pm. Geoff Emerick describes the atmosphere in the studio on this day: “A refreshed and rejuvenated George Harrison came back to the studio and oversaw the overdubbing of a couple of additional dilruba parts.”

George Martin recalls: “I was introduced to the dilruba, an Indian violin, in which a lot of sliding techniques are used.” These dilrubas were played by another unnamed musician, undoubtedly overdubbing himself (or herself), the result being the sliding melody lines heard throughout the song. The tape speed was increased to 52 1/2 cycles per second in order for it to sound slowed down when the tape was played back at the proper speed. George Martin recalls: “I was introduced to the dilruba, an Indian violin, in which a lot of sliding techniques are used.” These dilrubas were played by another unnamed musician, undoubtedly overdubbing himself (or herself), the result being the sliding melody lines heard throughout the song. The tape speed was increased to 52 1/2 cycles per second in order for it to sound slowed down when the tape was played back at the proper speed.

Geoff Emerick adds: “The other three Beatles were present at the session, but boredom set in quickly, so arrangements were made to have them listen to other works in progress in another control room. Deep in concentration, George (Harrison) had barely even noticed that the others had departed; he may have even welcomed them leaving him to work on his own.” This listening session is described in the book “The Beatles Recording Sessions” in this way: “In the control room of Studio One, between 11 pm and 12:30 am, tape operator Graham Kirkby oversaw a playback of the LP songs completed to date for any Beatle interested in listening." Geoff Emerick adds: “The other three Beatles were present at the session, but boredom set in quickly, so arrangements were made to have them listen to other works in progress in another control room. Deep in concentration, George (Harrison) had barely even noticed that the others had departed; he may have even welcomed them leaving him to work on his own.” This listening session is described in the book “The Beatles Recording Sessions” in this way: “In the control room of Studio One, between 11 pm and 12:30 am, tape operator Graham Kirkby oversaw a playback of the LP songs completed to date for any Beatle interested in listening."

However, it appears that at some point during this recording session, one or all of the other Beatles did pop down into the recording studio to contribute to the song musically. Engineer Richard Lush, in an Australian 2017 interview celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the "Sgt. Pepper" album, explains: "If you listen very carefully at the end of the sessions, there's a little bit of tambourine. Somebody walked into the studio while we were doing whatever it was, grabbed a tambourine and just played along. And if that's the only bit of - an exclusive here - that's the only piece of somebody else other than George or his Indian friends. It was either John or Paul or Ringo. So, they walked in downstairs and we couldn't see, you know, who did it. 'Well, there's a tambourine playing along; who's doing that?'" The tambourine can easily be heard in the final measures of the faster instrumental section of the song, which was actually the last section recorded on this day. However, it appears that at some point during this recording session, one or all of the other Beatles did pop down into the recording studio to contribute to the song musically. Engineer Richard Lush, in an Australian 2017 interview celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the "Sgt. Pepper" album, explains: "If you listen very carefully at the end of the sessions, there's a little bit of tambourine. Somebody walked into the studio while we were doing whatever it was, grabbed a tambourine and just played along. And if that's the only bit of - an exclusive here - that's the only piece of somebody else other than George or his Indian friends. It was either John or Paul or Ringo. So, they walked in downstairs and we couldn't see, you know, who did it. 'Well, there's a tambourine playing along; who's doing that?'" The tambourine can easily be heard in the final measures of the faster instrumental section of the song, which was actually the last section recorded on this day.

The dilrubas recorded at this session went onto track three of the four track tape and, since the tape was now full, a reduction mix was created which turned "take one" into "take two." Afterward, a demo mono mix was made in order for an acetate recording to be created for anyone who was interested to hear what the song sounded like thus far. By 2:15 am the following morning, the session was complete. The dilrubas recorded at this session went onto track three of the four track tape and, since the tape was now full, a reduction mix was created which turned "take one" into "take two." Afterward, a demo mono mix was made in order for an acetate recording to be created for anyone who was interested to hear what the song sounded like thus far. By 2:15 am the following morning, the session was complete.

One final day was determined to be required for completing George's "Within You Without You," this extensive session taking place on April 3rd, 1967 starting at 7 pm. EMI Studio One was chosen for this session because of it being a suitable size for orchestral recordings, this being the major element recorded on this day. This session is also noteworthy because, apart from the “Inner Groove” that was quickly recorded for the run-out groove of the British album, this was the final recording session for the entire “Sgt. Pepper” album. George Harrison may have been the only Beatle present on this day “with Paul somewhere over the Atlantic, winging his way to America” as Geoff Emerick put it, but it was a landmark day nonetheless. “As was becoming a habit,” Geoff Emerick added, “it was a marathon session, running until dawn the next day, but the results were nothing short of magical.” One final day was determined to be required for completing George's "Within You Without You," this extensive session taking place on April 3rd, 1967 starting at 7 pm. EMI Studio One was chosen for this session because of it being a suitable size for orchestral recordings, this being the major element recorded on this day. This session is also noteworthy because, apart from the “Inner Groove” that was quickly recorded for the run-out groove of the British album, this was the final recording session for the entire “Sgt. Pepper” album. George Harrison may have been the only Beatle present on this day “with Paul somewhere over the Atlantic, winging his way to America” as Geoff Emerick put it, but it was a landmark day nonetheless. “As was becoming a habit,” Geoff Emerick added, “it was a marathon session, running until dawn the next day, but the results were nothing short of magical.”

However, much preparatory work was needed from George Martin before this session could begin. The producer explained: “What was difficult was writing a score for the cellists and violinists that the English players would be able to play like the Indians. The dilruba player, for example, was doing all kinds of swoops and so I actually had to score that for strings and instruct the players to follow.” Concerning these “sliding techniques” as previously recorded by the Indian instrumentalists, George Martin stated: “This meant that in scoring for that track I had to make the string players play very much like Indian musicians, bending the notes, and with slurs between one note and the next.” Ian MacDonald explained in “Revolution In The Head,” “A less than enthusiastic (George) Martin did his best to catch the idiom, carefully marking in the microtonal slides that his London Symphony Orchestra players were required to imitate.” However, much preparatory work was needed from George Martin before this session could begin. The producer explained: “What was difficult was writing a score for the cellists and violinists that the English players would be able to play like the Indians. The dilruba player, for example, was doing all kinds of swoops and so I actually had to score that for strings and instruct the players to follow.” Concerning these “sliding techniques” as previously recorded by the Indian instrumentalists, George Martin stated: “This meant that in scoring for that track I had to make the string players play very much like Indian musicians, bending the notes, and with slurs between one note and the next.” Ian MacDonald explained in “Revolution In The Head,” “A less than enthusiastic (George) Martin did his best to catch the idiom, carefully marking in the microtonal slides that his London Symphony Orchestra players were required to imitate.”

Geoff Emerick explained the events of the day: "George Martin was conducting the same top-flight orchestral instrumentalists that worked on most of the rest of ‘Sgt Pepper,’ but despite their expertise, the musicians took a long time to get it right; I clearly remember the look of deep concentration on their faces as they struggled to master the complex score. It was painstaking, and it certainly was a challenge to the musicians, many of whom seemed to be getting a bit frustrated as the session wore on.” Geoff Emerick explained the events of the day: "George Martin was conducting the same top-flight orchestral instrumentalists that worked on most of the rest of ‘Sgt Pepper,’ but despite their expertise, the musicians took a long time to get it right; I clearly remember the look of deep concentration on their faces as they struggled to master the complex score. It was painstaking, and it certainly was a challenge to the musicians, many of whom seemed to be getting a bit frustrated as the session wore on.”

“The problem was that we all were trying to create a blend of East meets West – conventional orchestral instruments playing over nonconventional Indian instruments. There were no real bar lines in the Eastern music, just a bunch of sustained tones, most of which were playing in between the twelve notes used in Western music. That was a really hard session for George Martin – by the end of the night he was absolutely knackered. Thankfully he had the help of George Harrison, who acted as a bridge between the Indian tonalities and rhythms, which he understood quite well, and the Western sensibilities of George Martin and the classical musicians. I was never more impressed with both Georges than I was on that very special, almost spiritual night.” “The problem was that we all were trying to create a blend of East meets West – conventional orchestral instruments playing over nonconventional Indian instruments. There were no real bar lines in the Eastern music, just a bunch of sustained tones, most of which were playing in between the twelve notes used in Western music. That was a really hard session for George Martin – by the end of the night he was absolutely knackered. Thankfully he had the help of George Harrison, who acted as a bridge between the Indian tonalities and rhythms, which he understood quite well, and the Western sensibilities of George Martin and the classical musicians. I was never more impressed with both Georges than I was on that very special, almost spiritual night.”

While the recording of seasoned string players working off of a detailed score usually get it nearly perfect from their first try (witness “She’s Leaving Home” as a prime example), multiple attempts needed to be made this time around. Mark Lewisohn's book “The Beatles Recording Sessions” explained: “Each take of the strings overdub was recorded directly onto track three of the four-track tape, automatically wiping the previous attempt, and this procedure went on until everyone was satisfied that it could not be improved any further.” All of the session musicians were then dismissed for the evening at approximately 11 pm, leader Erich Gruenberg receiving pay of eleven pounds while the remainder of the players received the Musicians’ Union session rate of nine pounds. While the recording of seasoned string players working off of a detailed score usually get it nearly perfect from their first try (witness “She’s Leaving Home” as a prime example), multiple attempts needed to be made this time around. Mark Lewisohn's book “The Beatles Recording Sessions” explained: “Each take of the strings overdub was recorded directly onto track three of the four-track tape, automatically wiping the previous attempt, and this procedure went on until everyone was satisfied that it could not be improved any further.” All of the session musicians were then dismissed for the evening at approximately 11 pm, leader Erich Gruenberg receiving pay of eleven pounds while the remainder of the players received the Musicians’ Union session rate of nine pounds.

Geoff Emerick now describes the events of the rest of the session. “After the string overdubs were completed and the musicians had departed, we moved into Studio Two, where George Harrison began tuning his sitar, sitting cross-legged on a throw rug we had put down for him. George only had to overdub three or four licks in the instrumental section, but some of the drop-ins were a bit tricky and it took hours to do. None of us ever really appreciated how difficult the sitar was to play. Despite the fact that George Harrison was quite accomplished, it did always seem to take a lot of time to get his parts recorded whenever he picked the instrument up.” Geoff Emerick now describes the events of the rest of the session. “After the string overdubs were completed and the musicians had departed, we moved into Studio Two, where George Harrison began tuning his sitar, sitting cross-legged on a throw rug we had put down for him. George only had to overdub three or four licks in the instrumental section, but some of the drop-ins were a bit tricky and it took hours to do. None of us ever really appreciated how difficult the sitar was to play. Despite the fact that George Harrison was quite accomplished, it did always seem to take a lot of time to get his parts recorded whenever he picked the instrument up.”

As he usually did, George decided to fill the open spaces left in-between the melody lines played by the dilruba at this point in the song. (Witness “She Said She Said” and "I'm Looking Through You" for previous examples of George "filling in the gaps" of the melody lines.) Upon listening, there are actually eight sitar fills George added to the song's instrumental section on this day along with various vamping and mimicking of the dilruba melody line. Interestingly, it appears that an attempt was made to double-track George Harrison's sitar fills, the first one being double-tracked while the other riffs remained single tracked, undoubtedly realizing the difficulty they were having in getting this done and how much time they were taking. As he usually did, George decided to fill the open spaces left in-between the melody lines played by the dilruba at this point in the song. (Witness “She Said She Said” and "I'm Looking Through You" for previous examples of George "filling in the gaps" of the melody lines.) Upon listening, there are actually eight sitar fills George added to the song's instrumental section on this day along with various vamping and mimicking of the dilruba melody line. Interestingly, it appears that an attempt was made to double-track George Harrison's sitar fills, the first one being double-tracked while the other riffs remained single tracked, undoubtedly realizing the difficulty they were having in getting this done and how much time they were taking.

With the sitar work complete, they quickly went to the next task at hand. “Finally, with the lights down low and candles and incense burning,” Geoff Emerick continues, “George tackled the lead vocal, and he did a great job. Mind you, he does sound quite sleepy on it…hardly surprising since he’d been up all night working on the track! Fortunately, that lethargic quality seemed to perfectly complement the mood of the song.” It wasn’t only his lack of sleep that created the vocal feel needed for the song. The same finesse that the string musicians used had to also be perfected by George. As George Martin explains, he had to sing “the same tune as the dilruba in exactly the same way; the same kind of swoops that the dilruba does.” He worked at perfecting this art, recording each attempt directly onto track four of the tape, also wiping away any previous attempt in the process. The rhythm track he was recording his vocals onto was played back slightly faster as well, whiched changed the key of the song from C to C-sharp. With the sitar work complete, they quickly went to the next task at hand. “Finally, with the lights down low and candles and incense burning,” Geoff Emerick continues, “George tackled the lead vocal, and he did a great job. Mind you, he does sound quite sleepy on it…hardly surprising since he’d been up all night working on the track! Fortunately, that lethargic quality seemed to perfectly complement the mood of the song.” It wasn’t only his lack of sleep that created the vocal feel needed for the song. The same finesse that the string musicians used had to also be perfected by George. As George Martin explains, he had to sing “the same tune as the dilruba in exactly the same way; the same kind of swoops that the dilruba does.” He worked at perfecting this art, recording each attempt directly onto track four of the tape, also wiping away any previous attempt in the process. The rhythm track he was recording his vocals onto was played back slightly faster as well, whiched changed the key of the song from C to C-sharp.

Although it remains to be detected on the released version, “The Beatles Recording Sessions” indicates that George also recorded “a dash of acoustic guitar...just here and there” before the day's session was complete, all of George’s overdubs being preserved on track four of the master tape. With all of this accomplished, the production staff of George Martin, Geoff Emerick and 2nd engineer Richard Lush took the time to try their hand at creating a mono mix, making three attempts at mixing "part one" of the song and two tries at "part two and three" with the intention of editing them both together later. “The sun was rising as we staggered out of the studio the next morning,” said Geoff Emerick, “but I felt completely satisfied, proud of our accomplishment.” Although it remains to be detected on the released version, “The Beatles Recording Sessions” indicates that George also recorded “a dash of acoustic guitar...just here and there” before the day's session was complete, all of George’s overdubs being preserved on track four of the master tape. With all of this accomplished, the production staff of George Martin, Geoff Emerick and 2nd engineer Richard Lush took the time to try their hand at creating a mono mix, making three attempts at mixing "part one" of the song and two tries at "part two and three" with the intention of editing them both together later. “The sun was rising as we staggered out of the studio the next morning,” said Geoff Emerick, “but I felt completely satisfied, proud of our accomplishment.”

Later that day, April 4th, 1967, the same team of George Martin, Geoff Emerick and Richard Lush convened back in the EMI Studio Two control room at 7 pm to create both the mono and stereo mixes of the song for the released versions of the album. While remembering to increase the tape speed to match Harrison's vocals, they made six more attempts at ‘part one’ of the track (remix 6 through 11) and only one try at ‘parts two and three’ (remix 12) and then edited them together (remix 10 and 12) to get the final mono mix. Later that day, April 4th, 1967, the same team of George Martin, Geoff Emerick and Richard Lush convened back in the EMI Studio Two control room at 7 pm to create both the mono and stereo mixes of the song for the released versions of the album. While remembering to increase the tape speed to match Harrison's vocals, they made six more attempts at ‘part one’ of the track (remix 6 through 11) and only one try at ‘parts two and three’ (remix 12) and then edited them together (remix 10 and 12) to get the final mono mix.

However, at George Harrison’s request, they added a small bit of laughter at the end of the song as it faded away. “The laughs at the very end of the track was George Harrison,” George Martin explained. “He just thought it would be a good idea to put on it...I think he just wanted to relieve the tedium a bit. George was slightly embarrassed and defensive about his work. I was always conscious of that." In the Hunter Davies 1968 official biography "The Beatles," George himself explains: "Well, after all that long Indian stuff you want some light relief. It's a release after five minutes of sad music. You haven't got to take it all that seriously, you know. You were supposed to hear the audience anyway, as they listen to Sgt. Pepper's Show. That was the style of the album." However, at George Harrison’s request, they added a small bit of laughter at the end of the song as it faded away. “The laughs at the very end of the track was George Harrison,” George Martin explained. “He just thought it would be a good idea to put on it...I think he just wanted to relieve the tedium a bit. George was slightly embarrassed and defensive about his work. I was always conscious of that." In the Hunter Davies 1968 official biography "The Beatles," George himself explains: "Well, after all that long Indian stuff you want some light relief. It's a release after five minutes of sad music. You haven't got to take it all that seriously, you know. You were supposed to hear the audience anyway, as they listen to Sgt. Pepper's Show. That was the style of the album."

The production staff superimposed a bit of recorded laughter as they were editing together the two sections of the mono mix. According to “The Beatles Recording Sessions,” this laughter appeared “courtesy of the Abbey Road sound effects collection, ‘Volume 6: Applause and Laughter.’” But George Martin's 2008 book “Summer Of Love” explained this snippet as the group laughing after an undocumented take during the “Sgt. Pepper” sessions. In either case, the laughter enters quite abruptly and loudly in the final seconds of the mono mix. The production staff superimposed a bit of recorded laughter as they were editing together the two sections of the mono mix. According to “The Beatles Recording Sessions,” this laughter appeared “courtesy of the Abbey Road sound effects collection, ‘Volume 6: Applause and Laughter.’” But George Martin's 2008 book “Summer Of Love” explained this snippet as the group laughing after an undocumented take during the “Sgt. Pepper” sessions. In either case, the laughter enters quite abruptly and loudly in the final seconds of the mono mix.

The stereo mix was then tackled at the same increased tape speed, three mixes of "part one" (remixes 1 through 3) and two mixes of "parts two and three" (remixes 4 and 5), mixes 3 and 5 being selected to be joined together to form the completed stereo mix. During the editing of these two mixes, they once again superimposed a bit of laughter, taking a similar but noticeably different section of laughter than the one used for the mono mix. The initial tamboura drone, the tabla and also the introductory surmandal are heard in the left channel of the stereo mix, while the dilrubas are strictly in the right channel. The vocals, sitar and second surmandal appearance are centered in the mix while the acoustic guitar is apparently buried somewhere deep in the mix. The ending laughter is a little more subtle and is only heard in the right channel of the stereo mix. The stereo mix was then tackled at the same increased tape speed, three mixes of "part one" (remixes 1 through 3) and two mixes of "parts two and three" (remixes 4 and 5), mixes 3 and 5 being selected to be joined together to form the completed stereo mix. During the editing of these two mixes, they once again superimposed a bit of laughter, taking a similar but noticeably different section of laughter than the one used for the mono mix. The initial tamboura drone, the tabla and also the introductory surmandal are heard in the left channel of the stereo mix, while the dilrubas are strictly in the right channel. The vocals, sitar and second surmandal appearance are centered in the mix while the acoustic guitar is apparently buried somewhere deep in the mix. The ending laughter is a little more subtle and is only heard in the right channel of the stereo mix.

While George Martin described George's “Within You Without You” previously in 1979 as “a rather dreary song,” he changed his opinion as the years passed. "I actually think 'Within You Without You' would have benefitted a bit by being shorter, but this was a very interesting track," George Martin later said. "I find it more interesting now than I did then." This new opinion is also obvious by his choice to include a new mix of the recording on the 1996 compilation album “Anthology 2.” He was undoubtedly proud of the hard work he put into the string score and the performance he and George Harrison got out of the violinists and cellists. “From then on,” Geoff Emerick remembered, “many of George Martin’s orchestrations began exhibiting that same kind of Indian feel, with string sections doing slight pitch-bending. It actually put a stamp on his arrangements and gave them a unique sound.” The unique and vibrant mix of the song on “Anthology 2” has all of the elements of the released version, minus George’s lead vocals and the ending laughter. While George Martin described George's “Within You Without You” previously in 1979 as “a rather dreary song,” he changed his opinion as the years passed. "I actually think 'Within You Without You' would have benefitted a bit by being shorter, but this was a very interesting track," George Martin later said. "I find it more interesting now than I did then." This new opinion is also obvious by his choice to include a new mix of the recording on the 1996 compilation album “Anthology 2.” He was undoubtedly proud of the hard work he put into the string score and the performance he and George Harrison got out of the violinists and cellists. “From then on,” Geoff Emerick remembered, “many of George Martin’s orchestrations began exhibiting that same kind of Indian feel, with string sections doing slight pitch-bending. It actually put a stamp on his arrangements and gave them a unique sound.” The unique and vibrant mix of the song on “Anthology 2” has all of the elements of the released version, minus George’s lead vocals and the ending laughter.

Even more thrilling to hear was the new mix created by George Martin and his son Giles Martin for the Cirque du Soliel production and subsequent album “Love.” They worked tirelessly in order to combine rhythmic elements of “Tomorrow Never Knows” with George’s vocal track on “Within You Without You” to create what many view as the true crowning jewel of the album. This new mix, made sometime between 2004 and 2006, was constructed painstakingly to fit within the sometimes changing time signatures of the original recordings, this being accomplished through strategic editing and blending of certain elements of both songs. The second verse takes away the rhythms of “Tomorrow Never Knows” to reveal more of the tablas and dilrubas of “Within You Without You,” while the backward vocal lines heard in “Rain” are even thrown in at the close of the track. Very inventive indeed! Even more thrilling to hear was the new mix created by George Martin and his son Giles Martin for the Cirque du Soliel production and subsequent album “Love.” They worked tirelessly in order to combine rhythmic elements of “Tomorrow Never Knows” with George’s vocal track on “Within You Without You” to create what many view as the true crowning jewel of the album. This new mix, made sometime between 2004 and 2006, was constructed painstakingly to fit within the sometimes changing time signatures of the original recordings, this being accomplished through strategic editing and blending of certain elements of both songs. The second verse takes away the rhythms of “Tomorrow Never Knows” to reveal more of the tablas and dilrubas of “Within You Without You,” while the backward vocal lines heard in “Rain” are even thrown in at the close of the track. Very inventive indeed!

Sometime during 2016 or 2017, Giles Martin and engineer Sam Okell revisited the original tapes to create a new stereo mix of "Within You Without You" for inclusion on various editions of a 50th Anniversary release of "Sgt. Pepper." Also created during these sessions were two bonus tracks from the sessions for the song, one being the instrumental "take one" and the other being a track they called "George Coaching The Musicians" which was captured from rehearsals on that day in the studio. Sometime during 2016 or 2017, Giles Martin and engineer Sam Okell revisited the original tapes to create a new stereo mix of "Within You Without You" for inclusion on various editions of a 50th Anniversary release of "Sgt. Pepper." Also created during these sessions were two bonus tracks from the sessions for the song, one being the instrumental "take one" and the other being a track they called "George Coaching The Musicians" which was captured from rehearsals on that day in the studio.

Song Structure and Style

While many would agree that this song is one of the most unique Beatles tracks as far as structure is concerned, it does actually fall well within the “usual” range of formats within their catalog. The structure parses out to be ‘verse/ verse (altered)/ refrain/ instrumental/ verse (altered)/ refrain’ (or abcdbc). But, as usual for The Beatles, the arrangement takes many dives and jumps to make it anything but usual. This aside from the fact that George was trying, in a very simple way, to introduce traditional Eastern rhythms within a structure that would be more palatable to Western ears. While many would agree that this song is one of the most unique Beatles tracks as far as structure is concerned, it does actually fall well within the “usual” range of formats within their catalog. The structure parses out to be ‘verse/ verse (altered)/ refrain/ instrumental/ verse (altered)/ refrain’ (or abcdbc). But, as usual for The Beatles, the arrangement takes many dives and jumps to make it anything but usual. This aside from the fact that George was trying, in a very simple way, to introduce traditional Eastern rhythms within a structure that would be more palatable to Western ears.

Regarding playing the sitar, as well as understanding Eastern music, musician Ravi Shankar explained to Andy Babiuk in his 2001 book “Beatles Gear,” “It takes ten to fifteen years to reach a good standard, because it is not just the playing of it. You have to learn the whole musical system. So what George did, along with many others, was to take up the sitar and just start to play. They produced a sort of sound that to us sounded really ridiculous. It’s like if someone in Africa takes the violin and plays it and says, ‘How do you like this scratching sound?’ It takes a long time to produce the real sound and play the real music…When George showed his interest in sitar and said he would like to learn a little more, I told him very clearly that sitar is not like guitar where you can just learn it on your own. You have to undergo many years of study, like with the violin and cello or any of the Western classical instruments.” Regarding playing the sitar, as well as understanding Eastern music, musician Ravi Shankar explained to Andy Babiuk in his 2001 book “Beatles Gear,” “It takes ten to fifteen years to reach a good standard, because it is not just the playing of it. You have to learn the whole musical system. So what George did, along with many others, was to take up the sitar and just start to play. They produced a sort of sound that to us sounded really ridiculous. It’s like if someone in Africa takes the violin and plays it and says, ‘How do you like this scratching sound?’ It takes a long time to produce the real sound and play the real music…When George showed his interest in sitar and said he would like to learn a little more, I told him very clearly that sitar is not like guitar where you can just learn it on your own. You have to undergo many years of study, like with the violin and cello or any of the Western classical instruments.”

Even though it was only a matter of months after he received his initial intense study of the sitar and the music of India, what he and George Martin came up with was convincing enough for Western audiences - however “ridiculous” the raga masters in India may have felt that it was.

To start out the proceedings, we hear the tamboura drone fade in as a backdrop to the entire song, this appearing in the key of C# (vari-speeded up from the original key of C as evidenced on the album “Anthology 2”). Along with the tamboura drone is a dilruba, which shortly thereafter begins a melody line that is a variation of what we will hear later in the song, complete with triple swoops that definitely set the mood. The unnamed dilruba performer elevates the ‘Beatles Indian phase’ up to a much higher level than what they created with the somewhat "choppy" sitar introduction played by George himself on the previous years’ “Love You To.” Many first time listeners to “Within You Without You” may have said to themselves: “Oh boy, here we go again!,” but what they were truly experiencing was much closer to the real thing. To start out the proceedings, we hear the tamboura drone fade in as a backdrop to the entire song, this appearing in the key of C# (vari-speeded up from the original key of C as evidenced on the album “Anthology 2”). Along with the tamboura drone is a dilruba, which shortly thereafter begins a melody line that is a variation of what we will hear later in the song, complete with triple swoops that definitely set the mood. The unnamed dilruba performer elevates the ‘Beatles Indian phase’ up to a much higher level than what they created with the somewhat "choppy" sitar introduction played by George himself on the previous years’ “Love You To.” Many first time listeners to “Within You Without You” may have said to themselves: “Oh boy, here we go again!,” but what they were truly experiencing was much closer to the real thing.

This free-form intro continues with an upward glissando from the surmandal, which is the opposite direction featured in the downward run by the same instrument a couple of times on “Strawberry Fields Forever.” The 4/4 time signature then begins as the tabla enters immediately afterward, beating out a four measure introduction that is accompanied by the drone of the tambouras. This free-form intro continues with an upward glissando from the surmandal, which is the opposite direction featured in the downward run by the same instrument a couple of times on “Strawberry Fields Forever.” The 4/4 time signature then begins as the tabla enters immediately afterward, beating out a four measure introduction that is accompanied by the drone of the tambouras.

The first verse is a whopping twenty-two measures long, mostly in 4/4 time. George comes in singing the melody line (“we were talking…”) simultaneously with the now double-tracked dilruba which plays the identical melody line throughout the entire verse in traditional Indian style. Measure eighteen is the only measure to deviate from the 4/4 pattern, this adding another beat to make it a measure of 5/4 in order to fill out the lyric line “when they pass away.” The last two measures of the verse premier strings for the first time as the cellos play a swirly riff to act as as a segue into the verse that follows. The first verse is a whopping twenty-two measures long, mostly in 4/4 time. George comes in singing the melody line (“we were talking…”) simultaneously with the now double-tracked dilruba which plays the identical melody line throughout the entire verse in traditional Indian style. Measure eighteen is the only measure to deviate from the 4/4 pattern, this adding another beat to make it a measure of 5/4 in order to fill out the lyric line “when they pass away.” The last two measures of the verse premier strings for the first time as the cellos play a swirly riff to act as as a segue into the verse that follows.

The second verse is identical in format for the first twelve measures but then changes in scope thereafter, thereby consisting of eighteen measures, the sixteenth measure adding two additional beats so as to make this the only measure of 6/4 in an otherwise 4/4 verse. This is heard during the lyrics “if they only…,” the word “knew” extending into the seventeenth measure and thereby becoming the highest sung note in the entire song. Instrumentally, the string section kicks into full gear on this verse, playing subtle counter-melodies to command attention and add variance to the arrangement. The song then slips into neutral for a short time; the next seven seconds comprising a melodic riff played by dilruba and cello an octave apart without any time signature whatsoever. The second verse is identical in format for the first twelve measures but then changes in scope thereafter, thereby consisting of eighteen measures, the sixteenth measure adding two additional beats so as to make this the only measure of 6/4 in an otherwise 4/4 verse. This is heard during the lyrics “if they only…,” the word “knew” extending into the seventeenth measure and thereby becoming the highest sung note in the entire song. Instrumentally, the string section kicks into full gear on this verse, playing subtle counter-melodies to command attention and add variance to the arrangement. The song then slips into neutral for a short time; the next seven seconds comprising a melodic riff played by dilruba and cello an octave apart without any time signature whatsoever.

A "tabla fill" (this being equivalent to a "drum fill" as regularly performed by Ringo) brings in the 4/4 time signature once again to begin the refrain of the song. The refrain is twelve measures long, the only variance in time signature appearing this time in the third measure to allow for the lyric “-in yourself, no one,” one beat being added to comprise a measure of 5/4. The cellos appear to add to the drone of the tambouras creating a full bass effect on this part of the song, there being no need for bass guitar in this song after all. Another subtle melody line is played by the violins (featuring violinist Ralph Elman) to fill in the gap left after the line “no one else can make you change.” The violins also kick in to mimic the vocal and dilruba melody line during the key line “and life flows on within you and without you” while the cellos increase their volume to create the obvious conclusion that this phrase is the song's title. All voices and instruments (except for the drone) then drop out entirely for another stalled pause in the proceedings (where the edit is, by the way) to resume once again in the vibrant instrumental section that follows. A "tabla fill" (this being equivalent to a "drum fill" as regularly performed by Ringo) brings in the 4/4 time signature once again to begin the refrain of the song. The refrain is twelve measures long, the only variance in time signature appearing this time in the third measure to allow for the lyric “-in yourself, no one,” one beat being added to comprise a measure of 5/4. The cellos appear to add to the drone of the tambouras creating a full bass effect on this part of the song, there being no need for bass guitar in this song after all. Another subtle melody line is played by the violins (featuring violinist Ralph Elman) to fill in the gap left after the line “no one else can make you change.” The violins also kick in to mimic the vocal and dilruba melody line during the key line “and life flows on within you and without you” while the cellos increase their volume to create the obvious conclusion that this phrase is the song's title. All voices and instruments (except for the drone) then drop out entirely for another stalled pause in the proceedings (where the edit is, by the way) to resume once again in the vibrant instrumental section that follows.