Search by Keyword

|

"MAXWELL'S SILVER HAMMER"

(John Lennon – Paul McCartney)

One of the reasons for the popularity of the music of The Beatles was their ability to appeal to such a wide range audience. Young and old alike, no matter what genre of music appealed to you, The Beatles had something you could relate to. To this day, The Beatles are heard on radio stations that cater to harder-edged Classic Rock, lighter Easy Listening, and pop-oriented Oldies formats. If you like country music, that is touched on at various times on their albums. Even songs that harken back to the 30's and 40's find a place within their catalog.

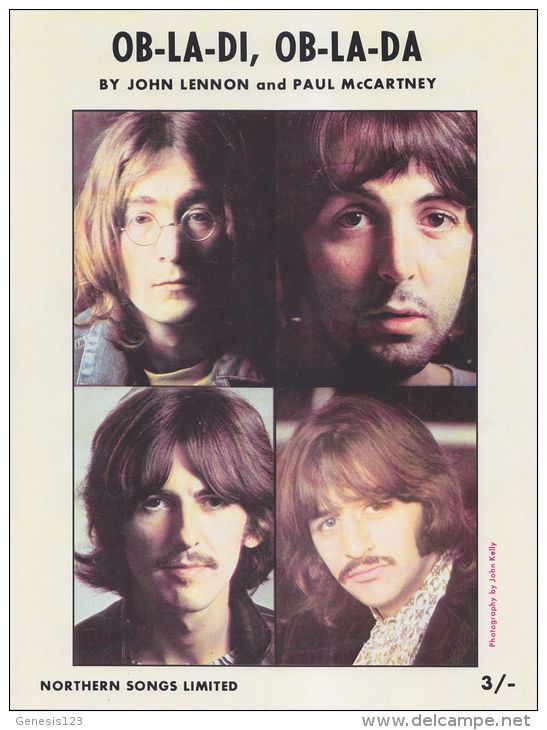

It was Paul's habit to keep the children in mind at times when composing songs for Beatles albums, resulting in songs like “Yellow Submarine” and “All Together Now” among others. Even “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” a song that became the primary focus of the "White Album" when it was initially released, had the sing-along quality that generally appeals to youth. It was Paul's habit to keep the children in mind at times when composing songs for Beatles albums, resulting in songs like “Yellow Submarine” and “All Together Now” among others. Even “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” a song that became the primary focus of the "White Album" when it was initially released, had the sing-along quality that generally appeals to youth.

John and George, however, were never too keen about including songs of this nature on their albums. When “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” was released in some countries as a single, for instance, and Paul expressed a desire to similarly release it that way officially worldwide, the others wouldn't have it. In 1969, for their album “Abbey Road,” Paul had the same intention for his similarly 'sing-songy' “Maxwell's Silver Hammer.” “He did everything to make it into a single and it never was and it never could've been,” John explained, “but he put guitar licks on it and he had somebody hitting iron pieces and we spent more money on that song than any of them in the whole album.” John and George, however, were never too keen about including songs of this nature on their albums. When “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” was released in some countries as a single, for instance, and Paul expressed a desire to similarly release it that way officially worldwide, the others wouldn't have it. In 1969, for their album “Abbey Road,” Paul had the same intention for his similarly 'sing-songy' “Maxwell's Silver Hammer.” “He did everything to make it into a single and it never was and it never could've been,” John explained, “but he put guitar licks on it and he had somebody hitting iron pieces and we spent more money on that song than any of them in the whole album.”

But the song's appeal was universal...at least at first. “'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' is something of Paul's which we'd spend a hell of a lot of time on and it is one of those instant whistle type of tunes which, I suppose, some people will hate and some people will really love,” George said just after "Abbey Road" was released. The song may not have been released as a single as Paul intended, but it definitely struck a chord with the youth despite the rather gruesome subject matter of the lyrics which parents, if any had been paying attention at the time, would probably have forbidden their kids to listen to. But the song's appeal was universal...at least at first. “'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' is something of Paul's which we'd spend a hell of a lot of time on and it is one of those instant whistle type of tunes which, I suppose, some people will hate and some people will really love,” George said just after "Abbey Road" was released. The song may not have been released as a single as Paul intended, but it definitely struck a chord with the youth despite the rather gruesome subject matter of the lyrics which parents, if any had been paying attention at the time, would probably have forbidden their kids to listen to.

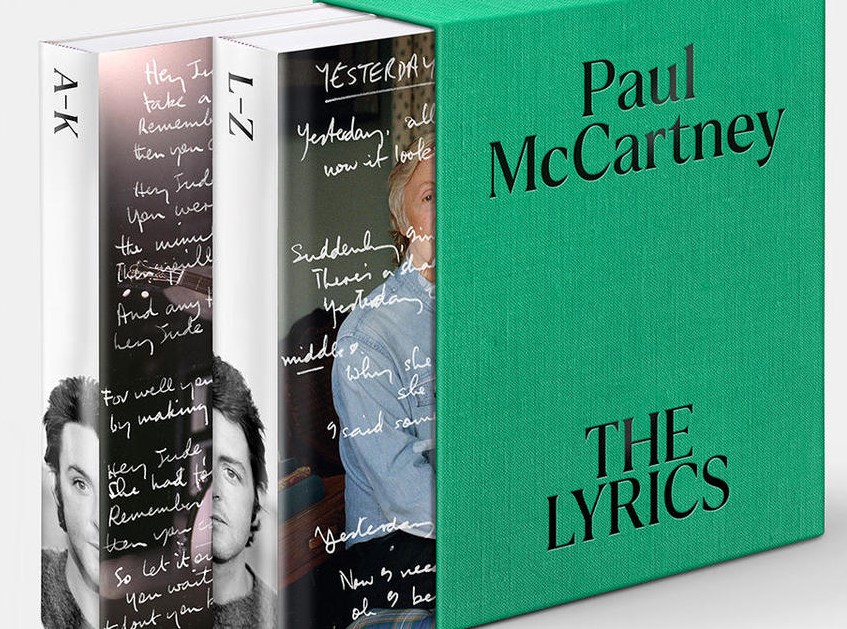

Songwriting History

"'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' was my analogy for when something goes wrong out of the blue, as it so often does, as I was beginning to find out at that time in my life," Paul writes in his book "Many Years From Now." He continues: "I wanted something symbolic of that, so to me it was some fictitious character called Maxwell with a silver hammer. I don't know why it was silver, it just sounded better than 'Maxwell's Hammer.' It was needed for scanning. We still use that expression even now when something unexpected happens." In his 2021 book "The Lyrics," Paul adds: "The thing about Maxwell is that he's a serial killer, and his hammer isn't an ordinary household hammer but, as I envision it, one that doctors use to hit your knee. Not made of rubber, though. Silver...This song is also an analogy for when something goes wrong out of the blue, as I was beginning to find happening around this time in our business dealings." "'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' was my analogy for when something goes wrong out of the blue, as it so often does, as I was beginning to find out at that time in my life," Paul writes in his book "Many Years From Now." He continues: "I wanted something symbolic of that, so to me it was some fictitious character called Maxwell with a silver hammer. I don't know why it was silver, it just sounded better than 'Maxwell's Hammer.' It was needed for scanning. We still use that expression even now when something unexpected happens." In his 2021 book "The Lyrics," Paul adds: "The thing about Maxwell is that he's a serial killer, and his hammer isn't an ordinary household hammer but, as I envision it, one that doctors use to hit your knee. Not made of rubber, though. Silver...This song is also an analogy for when something goes wrong out of the blue, as I was beginning to find happening around this time in our business dealings."

Former Apple employee Tony King expands on the song's meaning a little further in Steve Turner's book “A Hard Day's Write,” by relating a conversation he had with John Lennon concerning his song “Instant Karma.” “John told me that 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' was about the law of karma. We were talking one day about 'Instant Karma' because something had happened where he's been clobbered and he'd said that this was an example of instant karma. I asked him whether he believed that theory. He said that he did and that 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' was the first song that they'd made about that. He said that the idea behind the song was that the minute you do something that's not right, Maxwell's silver hammer will come down on your head.” Former Apple employee Tony King expands on the song's meaning a little further in Steve Turner's book “A Hard Day's Write,” by relating a conversation he had with John Lennon concerning his song “Instant Karma.” “John told me that 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' was about the law of karma. We were talking one day about 'Instant Karma' because something had happened where he's been clobbered and he'd said that this was an example of instant karma. I asked him whether he believed that theory. He said that he did and that 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' was the first song that they'd made about that. He said that the idea behind the song was that the minute you do something that's not right, Maxwell's silver hammer will come down on your head.”

“The song epitomizes the downfalls of life,” Paul explains in the “Beatles Anthology” book. "Just when everything is going smoothly – 'Bang! Bang!' - down comes Maxwell's silver hammer and ruins everything."

In order to incorporate the instant karma theme, Paul needed to concoct a story for the song. “Some of my songs are based on personal experience, but my style is to veil it,” Paul continues in the “Anthology” book. “A lot of them are made up, like 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' which is the kind of song I like to write. It's just a silly story about all these people I'd never met. It's just like writing a play: you don't have to know the people, you just make them up. I remember George once saying to me, 'I couldn't write songs like that.' He writes more from personal experience. John's style was to show the naked truth. If I was painter, I'd probably mask things a little bit more than some people.” In order to incorporate the instant karma theme, Paul needed to concoct a story for the song. “Some of my songs are based on personal experience, but my style is to veil it,” Paul continues in the “Anthology” book. “A lot of them are made up, like 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' which is the kind of song I like to write. It's just a silly story about all these people I'd never met. It's just like writing a play: you don't have to know the people, you just make them up. I remember George once saying to me, 'I couldn't write songs like that.' He writes more from personal experience. John's style was to show the naked truth. If I was painter, I'd probably mask things a little bit more than some people.”

A good example of masking, or veiling, contained within the premise of “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” is found within its very first line, a reference to “Pataphisics.” This was a word invented by French dramatist Alfred Jarry, the French pioneer of absurd theater from the turn of the century, to describe a branch of metaphysics. Paul became interested in the works of Alfred Jarry on January 10th, 1966 when, while driving from London to Liverpool, he heard a re-broadcast on BBC Radio 3 of one of his plays, “Ubu Cocu,” on BBC radio. "Zooming up the motorway from London to Liverpool in (my) Aston Martin, I fiddled around on the radio for something and happened on a BBC Radio 3 production of 'Ubu Cocu,'" Paul remembers in his 2021 book "The Lyrics." “It was the best radio play I had ever heard in my life,” Paul relates in “Many Years From Now,” “and the best production, and Ubu was so brilliantly played. It was just a sensation. That was one of the big things of the period for me.” (As a sidenote, Paul incorporated the name of this play to a 90's radio show of his own which he called “Oobu Joobu.”) A good example of masking, or veiling, contained within the premise of “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” is found within its very first line, a reference to “Pataphisics.” This was a word invented by French dramatist Alfred Jarry, the French pioneer of absurd theater from the turn of the century, to describe a branch of metaphysics. Paul became interested in the works of Alfred Jarry on January 10th, 1966 when, while driving from London to Liverpool, he heard a re-broadcast on BBC Radio 3 of one of his plays, “Ubu Cocu,” on BBC radio. "Zooming up the motorway from London to Liverpool in (my) Aston Martin, I fiddled around on the radio for something and happened on a BBC Radio 3 production of 'Ubu Cocu,'" Paul remembers in his 2021 book "The Lyrics." “It was the best radio play I had ever heard in my life,” Paul relates in “Many Years From Now,” “and the best production, and Ubu was so brilliantly played. It was just a sensation. That was one of the big things of the period for me.” (As a sidenote, Paul incorporated the name of this play to a 90's radio show of his own which he called “Oobu Joobu.”)

Then a few months later, in July of 1966, the Royal Court Theatre in London put on a production of a related Alfred Jarry play entitled “Ubu Roi,” which Paul attended. This was the better-known play by Alfred Jarry, subtitled "a pataphysical extravaganza," "'Pataphysical' (being) a nonsense word Jarry made up to poke fun at toffee-nosed academics," Paul explained in "The Lyrics." The lead actor cast for this play was Max Wall, a veteran vaudevillian whom Jane Asher, Paul's girlfriend, particularly liked in this role. Paul continued to immerse himself in the writings of Alfred Jarry, especially the “science” created by him that Jarry termed “pataphysics,” which some describe as the science of imaginary solutions. Then a few months later, in July of 1966, the Royal Court Theatre in London put on a production of a related Alfred Jarry play entitled “Ubu Roi,” which Paul attended. This was the better-known play by Alfred Jarry, subtitled "a pataphysical extravaganza," "'Pataphysical' (being) a nonsense word Jarry made up to poke fun at toffee-nosed academics," Paul explained in "The Lyrics." The lead actor cast for this play was Max Wall, a veteran vaudevillian whom Jane Asher, Paul's girlfriend, particularly liked in this role. Paul continued to immerse himself in the writings of Alfred Jarry, especially the “science” created by him that Jarry termed “pataphysics,” which some describe as the science of imaginary solutions.

“I put that in one of the Beatles songs,” Paul continues, referring to “Maxwell's Silver Hammer.” “'Joan was quizzical, studied 'pataphysical science in the home...' Nobody knows what it means; I only explained it to Linda just the other day. That's the lovely thing about it. I am the only person who ever put the name of 'pataphysics' into the record charts, c'mon! It was great. I love those surreal little touches. That was the big difference between me and John: whereas John shouted it from the rooftops, I often just whispered it in the drawing room, thinking that was enough." In "The Lyrics," Paul adds: "I liked that people wouldn't necessarily know what 'pataphysical' was, so I was being a little bit obscure on purpose." “I put that in one of the Beatles songs,” Paul continues, referring to “Maxwell's Silver Hammer.” “'Joan was quizzical, studied 'pataphysical science in the home...' Nobody knows what it means; I only explained it to Linda just the other day. That's the lovely thing about it. I am the only person who ever put the name of 'pataphysics' into the record charts, c'mon! It was great. I love those surreal little touches. That was the big difference between me and John: whereas John shouted it from the rooftops, I often just whispered it in the drawing room, thinking that was enough." In "The Lyrics," Paul adds: "I liked that people wouldn't necessarily know what 'pataphysical' was, so I was being a little bit obscure on purpose."

One can easily speculate, given these circumstances, that Paul equated “Pataphysics,” or “the science of imaginary solutions,” with what John described as “Instant Karma”: the moment you think things are going perfectly for you, that you feel invincible, a sudden disaster is the “solution” of bringing you back down to earth, a blow to the ego as a reminder of your humanity. And as far as speculation goes, could actor Max Wall playing the lead role of King Ubu in the Alfred Jarry play that Paul attended in July of 1966 influenced the main character in his song being named “Maxwell,” even if only subconsciously? In his book "The Lyrics," Paul speculates differently: "Maxwell is possibly a descendant of James Clerk Maxwell, who was a pioneer of electromagnetism. Edision is obviously related to Thomas Edison. They're two inventor types." Ah, the wonderful fun of speculation! One can easily speculate, given these circumstances, that Paul equated “Pataphysics,” or “the science of imaginary solutions,” with what John described as “Instant Karma”: the moment you think things are going perfectly for you, that you feel invincible, a sudden disaster is the “solution” of bringing you back down to earth, a blow to the ego as a reminder of your humanity. And as far as speculation goes, could actor Max Wall playing the lead role of King Ubu in the Alfred Jarry play that Paul attended in July of 1966 influenced the main character in his song being named “Maxwell,” even if only subconsciously? In his book "The Lyrics," Paul speculates differently: "Maxwell is possibly a descendant of James Clerk Maxwell, who was a pioneer of electromagnetism. Edision is obviously related to Thomas Edison. They're two inventor types." Ah, the wonderful fun of speculation!

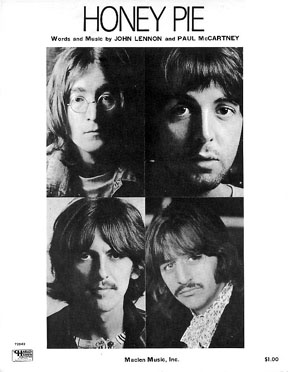

Nonetheless, the dark comedy contained in the lyrics is obvious. George, when describing the song shortly after its release, calls our attention to this: “It's a 'Honey Pie' sort of fun thing, but this is pretty sick, because the guy keeps killing everybody...It's kind of a drag because Maxwell keeps destroying everyone, like his girlfriend, the school teacher, and then, finally, the judge.” George also described the song that year as "one of those instant, whistle-along tunes which some people hate and other people really like. It's a fun song, but it's kind of sick, because Maxwell keeps on killing everyone." During January 1969 rehearsals of the song at Twickenham Film Studios, Paul explained that Maxwell "would be very scholarly; just very straight in a striped tie and a blazer." Nonetheless, the dark comedy contained in the lyrics is obvious. George, when describing the song shortly after its release, calls our attention to this: “It's a 'Honey Pie' sort of fun thing, but this is pretty sick, because the guy keeps killing everybody...It's kind of a drag because Maxwell keeps destroying everyone, like his girlfriend, the school teacher, and then, finally, the judge.” George also described the song that year as "one of those instant, whistle-along tunes which some people hate and other people really like. It's a fun song, but it's kind of sick, because Maxwell keeps on killing everyone." During January 1969 rehearsals of the song at Twickenham Film Studios, Paul explained that Maxwell "would be very scholarly; just very straight in a striped tie and a blazer."

Ian MacDonald, in his book “Revolution In The Head,” describes the song as “the cheery tale of a homicidal maniac,” adding that it “represents by far (Paul's) worst lapse of taste under the auspices of The Beatles.” Then again, if you like the dark British humor of, say, “Monty Python's Flying Circus,” whose very first episode aired simultaneously with the release of the “Abbey Road” album in Britain, the fact that the unlikely hero in Paul's song is a murderer while the music lends itself to a children's song fits in nicely with what was deemed funny at the time. Ian MacDonald, in his book “Revolution In The Head,” describes the song as “the cheery tale of a homicidal maniac,” adding that it “represents by far (Paul's) worst lapse of taste under the auspices of The Beatles.” Then again, if you like the dark British humor of, say, “Monty Python's Flying Circus,” whose very first episode aired simultaneously with the release of the “Abbey Road” album in Britain, the fact that the unlikely hero in Paul's song is a murderer while the music lends itself to a children's song fits in nicely with what was deemed funny at the time.

In "The Lyrics," Paul writes: "Also invoked is the world of the children's nursery thyme, where people are always getting their heads chopped off - and of course, there's also the 'Queen Of Hearts' from 'Alice's Adventures In Wonderland,' who's always saying, 'Off with their heads!' Ian Brady and Myra Hindley, the Moors murderers, had been jailed for life in 1966 for committing serial mruders. That case was quite likely in my mind, as it was front page news in the UK." In "The Lyrics," Paul writes: "Also invoked is the world of the children's nursery thyme, where people are always getting their heads chopped off - and of course, there's also the 'Queen Of Hearts' from 'Alice's Adventures In Wonderland,' who's always saying, 'Off with their heads!' Ian Brady and Myra Hindley, the Moors murderers, had been jailed for life in 1966 for committing serial mruders. That case was quite likely in my mind, as it was front page news in the UK."

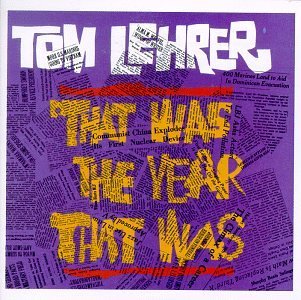

In fact, regarding inappropriate humor, during the rehearsals of "Maxwell's Silver Hammer" at Twickenham Studios in January of 1969, Paul described the song by saying, "It's like Tom Lehrer, that one." Satirist and Harvard lecturer Tom Lehrer, most noted for his popular 1965 album "That Was The Year That Was," specialized in topical and sometimes dark subject matter within the framework of older music styles. For example, one of his earlier compositions, "Poisoning Pigeons In The Park," contains lyrics that refer to a method used by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service of killing pigeons in Boston by feeding them strychrine-treated corn. With this as a reference, lyrically as well as musically, murdering people with a silver hammer is not too far removed! In fact, regarding inappropriate humor, during the rehearsals of "Maxwell's Silver Hammer" at Twickenham Studios in January of 1969, Paul described the song by saying, "It's like Tom Lehrer, that one." Satirist and Harvard lecturer Tom Lehrer, most noted for his popular 1965 album "That Was The Year That Was," specialized in topical and sometimes dark subject matter within the framework of older music styles. For example, one of his earlier compositions, "Poisoning Pigeons In The Park," contains lyrics that refer to a method used by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service of killing pigeons in Boston by feeding them strychrine-treated corn. With this as a reference, lyrically as well as musically, murdering people with a silver hammer is not too far removed!

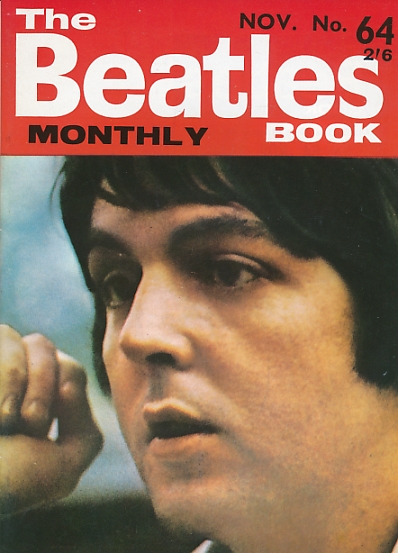

As to the time of writing, the November 1968 issue of “The Beatles Book” magazine reported that “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” was an existing song that had not been recorded in time for inclusion on the “White Album,” which was released that month. To be more precise, Paul included the first verse of this song, up to and including the lyric "Let me take you out to the pictures Jo-o-o-oan," in a notebook he had taken to India during their trip there to study Transendental Meditation with the Maharishi. On an opening page of the notebook he wrote, "Spring Songs, Rishikesh 1968," which would indicate that he began writing the song during his stay in India, this being between March and May of that year. When Paul introduced the song to The Beatles in January of 1969 during the “Get Back / Let It Be” sessions, he had written a little more of the song by then, the chorus and a verse-and-a-half being heard during these rehearsals. We do know, however, that all the lyrics were in place when Paul recorded the lead vocals for the song on July 10th, 1969. As to the time of writing, the November 1968 issue of “The Beatles Book” magazine reported that “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” was an existing song that had not been recorded in time for inclusion on the “White Album,” which was released that month. To be more precise, Paul included the first verse of this song, up to and including the lyric "Let me take you out to the pictures Jo-o-o-oan," in a notebook he had taken to India during their trip there to study Transendental Meditation with the Maharishi. On an opening page of the notebook he wrote, "Spring Songs, Rishikesh 1968," which would indicate that he began writing the song during his stay in India, this being between March and May of that year. When Paul introduced the song to The Beatles in January of 1969 during the “Get Back / Let It Be” sessions, he had written a little more of the song by then, the chorus and a verse-and-a-half being heard during these rehearsals. We do know, however, that all the lyrics were in place when Paul recorded the lead vocals for the song on July 10th, 1969.

His notebook also includes the more detailed composition of the lyrics for this song, as seen above. Since many of these lyrics weren't included in the filmed Twickenham sessions of early January 1969, the writings in his notebook must have been added to in the following months, a glued insert even being added to the notebook at some point. Interestingly, changes were also made afterward, this notebook conting lyrics such as a crossed out "how can she avoid him a third time" and then "how can she avoid an unpleasant scene" instead of the finished "wishing to avoid an unpleasant scene." Another crossed out phrase was "and as she turns her back to the board" being replaced by "but when she turns her back on the boy." His notebook also includes the more detailed composition of the lyrics for this song, as seen above. Since many of these lyrics weren't included in the filmed Twickenham sessions of early January 1969, the writings in his notebook must have been added to in the following months, a glued insert even being added to the notebook at some point. Interestingly, changes were also made afterward, this notebook conting lyrics such as a crossed out "how can she avoid him a third time" and then "how can she avoid an unpleasant scene" instead of the finished "wishing to avoid an unpleasant scene." Another crossed out phrase was "and as she turns her back to the board" being replaced by "but when she turns her back on the boy."

When asked by Playboy magazine in 1980 if he had any part in writing the song, John replied, “That's Paul. I hate it,” another time calling it “a typical McCartney single, or whatever,” and yet another time “more of Paul's granny music.” So I guess it's safe to say that this is entirely a McCartney composition, wouldn't you think? When asked by Playboy magazine in 1980 if he had any part in writing the song, John replied, “That's Paul. I hate it,” another time calling it “a typical McCartney single, or whatever,” and yet another time “more of Paul's granny music.” So I guess it's safe to say that this is entirely a McCartney composition, wouldn't you think?

Recording History

The first time "Maxwell's Silver Hammer" was recorded was on January 3rd, 1969, in Twickenham Film Studios during their filmed rehearsals for what became the "Let It Be" album and movie.

This was their second day of rehearsals at Twickenham Film Studios and, with John late in arriving, Paul ran through a number of work-in-progress songs on piano for the others to hear, “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” being one of them. Lyrically, Paul only had the first verse, the chorus, and the first half of the second verse written at this time, and the arrangement still needed refining. Later that day, after John arrived, Paul led them through a total of ten rehearsals of the song, which he was referring to as “the corny one.” A small segment of one of these rehearsals, with Paul on bass and calling out the chords for John and George, made it into the released “Let It Be” movie. Paul then switched to piano at George's suggestion and, with George on a Fender Bass VI, they rehearsed a little more before leaving it for another day. During these rehearsals, Paul suggests, "Originally, I was trying to get a hammer, which we might get Mal (Evans) to do. A hammer, like on an anvil. A big hammer on an anvil - you can't make it with anything else. Bang, bang!" This was their second day of rehearsals at Twickenham Film Studios and, with John late in arriving, Paul ran through a number of work-in-progress songs on piano for the others to hear, “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” being one of them. Lyrically, Paul only had the first verse, the chorus, and the first half of the second verse written at this time, and the arrangement still needed refining. Later that day, after John arrived, Paul led them through a total of ten rehearsals of the song, which he was referring to as “the corny one.” A small segment of one of these rehearsals, with Paul on bass and calling out the chords for John and George, made it into the released “Let It Be” movie. Paul then switched to piano at George's suggestion and, with George on a Fender Bass VI, they rehearsed a little more before leaving it for another day. During these rehearsals, Paul suggests, "Originally, I was trying to get a hammer, which we might get Mal (Evans) to do. A hammer, like on an anvil. A big hammer on an anvil - you can't make it with anything else. Bang, bang!"

The next day they worked on the song was January 7th, 1969. "Mal, we should get a hammer," Paul instructed their assistant, "and an anvil." According to Kenneth Womack's book "Living The Beatles Legend: The Untold Story Of Mal Evans," "For a moment, Mal seemed perplexed by the unusual request. Not bothering to ask any questions, though, he simply shrugged and went about the business of fulfilling Paul's wishes during their upcoming break. By the time the boys returned from lunch, Mal had rounded up an anvil from a West End outfit that specialized in theatrical props. With the anvil in place, he soon learned that Paul expected him to bang the rented hunk of steel during the chorus of 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer.'" They went through the song eighteen times, working on the arrangement as they went along. They came up with an idea to whistle during certain segments of the song, such as just before the verses, and George worked out a vocal harmony for the choruses. Another idea, as witnessed in the 2021 Peter Jackson "Get Back" series, was to end the song in the old fashioned stereotypical style heard on the 1955 classic "(We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock," Mal adding in two more strategic anvil hits for good measure. A portion of one of these rehearsals, with Mal struggling to hit the anvil on the proper beats, appears in the “Let It Be” movie as well. The next day they worked on the song was January 7th, 1969. "Mal, we should get a hammer," Paul instructed their assistant, "and an anvil." According to Kenneth Womack's book "Living The Beatles Legend: The Untold Story Of Mal Evans," "For a moment, Mal seemed perplexed by the unusual request. Not bothering to ask any questions, though, he simply shrugged and went about the business of fulfilling Paul's wishes during their upcoming break. By the time the boys returned from lunch, Mal had rounded up an anvil from a West End outfit that specialized in theatrical props. With the anvil in place, he soon learned that Paul expected him to bang the rented hunk of steel during the chorus of 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer.'" They went through the song eighteen times, working on the arrangement as they went along. They came up with an idea to whistle during certain segments of the song, such as just before the verses, and George worked out a vocal harmony for the choruses. Another idea, as witnessed in the 2021 Peter Jackson "Get Back" series, was to end the song in the old fashioned stereotypical style heard on the 1955 classic "(We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock," Mal adding in two more strategic anvil hits for good measure. A portion of one of these rehearsals, with Mal struggling to hit the anvil on the proper beats, appears in the “Let It Be” movie as well.

The next day, January 8th, 1969, The Beatles were generally in good spirits and, among many other things, went through thirteen rehearsals of “Maxwell's Silver Hammer.” John joined George in singing harmony during these rehearsals as Mal Evans transcribed the song's evolving lyrics onto Apple Corps letterhead and jotted down performance notes to guide his efforts on the anvil. Paul here began adlibbing lyrics in the third verse about a judge and courtroom scene, although he had yet to take the time to formally write these lyrics. The next day, January 8th, 1969, The Beatles were generally in good spirits and, among many other things, went through thirteen rehearsals of “Maxwell's Silver Hammer.” John joined George in singing harmony during these rehearsals as Mal Evans transcribed the song's evolving lyrics onto Apple Corps letterhead and jotted down performance notes to guide his efforts on the anvil. Paul here began adlibbing lyrics in the third verse about a judge and courtroom scene, although he had yet to take the time to formally write these lyrics.

The atmosphere became much more tense the next day they rehearsed the song, which was on January 10th, 1969. After a disagreement between Paul and George in the earlier part of the day, George decided to quit the group during their lunch break, exclaiming “See you 'round the clubs” just before he walked out the door. The other three, with Yoko sitting in George's spot, let off some steam with some incoherent jamming along with Yoko wailing into George's microphone. Determined to get back to business, they then went through some of the songs they had previously been working on, “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” being one of them. They ran through portions of the song four times, Paul singing one rendition as if he were drunk and John humorously singing lead on another with an exaggerated German accent, which appeared to display his distaste for the song. And with that, the song was dropped for consideration for the “Let It Be” project. The atmosphere became much more tense the next day they rehearsed the song, which was on January 10th, 1969. After a disagreement between Paul and George in the earlier part of the day, George decided to quit the group during their lunch break, exclaiming “See you 'round the clubs” just before he walked out the door. The other three, with Yoko sitting in George's spot, let off some steam with some incoherent jamming along with Yoko wailing into George's microphone. Determined to get back to business, they then went through some of the songs they had previously been working on, “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” being one of them. They ran through portions of the song four times, Paul singing one rendition as if he were drunk and John humorously singing lead on another with an exaggerated German accent, which appeared to display his distaste for the song. And with that, the song was dropped for consideration for the “Let It Be” project.

Nearly six months later, on July 9th, 1969, the song was resurrected by Paul for inclusion on what was to be their final recorded album “Abbey Road.” They met in EMI Studio Two at 2:30 pm to start work on officially recording the song for the first time, this day going down in Beatles history as a somewhat historic day.

Eight days earlier, on July1st, 1969, John and Yoko had been in a serious automobile accident while on vacation in North Scotland. They both ended up in the hospital, John receiving seventeen stitches and Yoko being monitored more closely because she was pregnant at the time. The Beatles had been busy in the recording studio without him working on the album, but this day, July 9th, was the first day that John joined them after the accident. Yoko, while in a fragile condition, was present as well. Eight days earlier, on July1st, 1969, John and Yoko had been in a serious automobile accident while on vacation in North Scotland. They both ended up in the hospital, John receiving seventeen stitches and Yoko being monitored more closely because she was pregnant at the time. The Beatles had been busy in the recording studio without him working on the album, but this day, July 9th, was the first day that John joined them after the accident. Yoko, while in a fragile condition, was present as well.

Phil McDonald, engineer on this session, recalls: “We were all waiting for him and Yoko to arrive. Paul, George, Ringo downstairs (on the studio floor) and us upstairs (in the control room). They didn't know what state he would be in. There was a definite 'vibe'; they were almost afraid of Lennon before he arrived, because they didn't know what he would be like. I got the feeling that the three of them were a little bit scared of him. When he did come in it was a relief and they got together fairly well. John was a powerful figure, especially with Yoko – a double strength.” Phil McDonald, engineer on this session, recalls: “We were all waiting for him and Yoko to arrive. Paul, George, Ringo downstairs (on the studio floor) and us upstairs (in the control room). They didn't know what state he would be in. There was a definite 'vibe'; they were almost afraid of Lennon before he arrived, because they didn't know what he would be like. I got the feeling that the three of them were a little bit scared of him. When he did come in it was a relief and they got together fairly well. John was a powerful figure, especially with Yoko – a double strength.”

Engineer Geoff Emerick, who claims to be present on this day although not engineering this session, explains what occurred just after John and Yoko's arrival. “The door burst open again and four men in brown coats began wheeling in a large, heavy object,” Emerick relates in his book “Here, There And Everywhere.” “For a moment, I thought it was a piano coming in from one of the other studios, but it soon dawned on me that these were proper deliverymen: the brown coats they were wearing had the word 'Harrods' inscribed on the back. The object being delivered was, in fact, a bed. Jaws dropping, we all watched as it was brought into the studio and carefully positioned by the stairs, across from the tea-and-toast setup. More brown coats appeared with sheets and pillows and somberly made the bed up.” Engineer Geoff Emerick, who claims to be present on this day although not engineering this session, explains what occurred just after John and Yoko's arrival. “The door burst open again and four men in brown coats began wheeling in a large, heavy object,” Emerick relates in his book “Here, There And Everywhere.” “For a moment, I thought it was a piano coming in from one of the other studios, but it soon dawned on me that these were proper deliverymen: the brown coats they were wearing had the word 'Harrods' inscribed on the back. The object being delivered was, in fact, a bed. Jaws dropping, we all watched as it was brought into the studio and carefully positioned by the stairs, across from the tea-and-toast setup. More brown coats appeared with sheets and pillows and somberly made the bed up.”

Technician Martin Benge relates: “We were setting up the microphones for the session and this huge double-bed arrived. An ambulance brought Yoko in and she was lowered down onto the bed, we set up a microphone over her in case she wanted to participate and then we all carried on as before! We were saying, 'Now we've seen it all, folks!'” Technician Martin Benge relates: “We were setting up the microphones for the session and this huge double-bed arrived. An ambulance brought Yoko in and she was lowered down onto the bed, we set up a microphone over her in case she wanted to participate and then we all carried on as before! We were saying, 'Now we've seen it all, folks!'”

Geoff Emerick continues about the events of that day and the next few weeks: “It wasn't as if Yoko was just lying in that bed resting quietly, either – there was a long line of visitors there by her bedside paying supplication, almost all the time. Various Beatles would be recording in one end of the room, and she would be lying there at the other end, chatting with friends, making her presence all the more obvious – and aggravating – to the rest of the band. George Martin had returned on the premise that it was going to be like the good old days, but we had never had a Beatle wife in bed in the studio with us in the old days. That probably explained why he seemed so depressed and frustrated during those weeks.” Producer Ron Richards explains, regarding the activities during that period, that “the bed was wheeled around between studios two and three, depending on where John was working.” Geoff Emerick continues about the events of that day and the next few weeks: “It wasn't as if Yoko was just lying in that bed resting quietly, either – there was a long line of visitors there by her bedside paying supplication, almost all the time. Various Beatles would be recording in one end of the room, and she would be lying there at the other end, chatting with friends, making her presence all the more obvious – and aggravating – to the rest of the band. George Martin had returned on the premise that it was going to be like the good old days, but we had never had a Beatle wife in bed in the studio with us in the old days. That probably explained why he seemed so depressed and frustrated during those weeks.” Producer Ron Richards explains, regarding the activities during that period, that “the bed was wheeled around between studios two and three, depending on where John was working.”

“I was ill after the accident when they did most of that track,” John explained in interview about "Maxwell's Silver Hammer," “and it really ground George and Ringo into the ground recording it, you know. I wasn't on 'Maxwell.'” Geoff Emerick continues: “There was a distinct change in the atmosphere after John and Yoko arrived, although personally I felt it had more to do with Lennon being there than his bedridden wife. He was grouchy and moody, and he flatly refused to participate at all in the making of 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer,' which he derisively dismissed as 'just more of Paul's granny music.'” “I was ill after the accident when they did most of that track,” John explained in interview about "Maxwell's Silver Hammer," “and it really ground George and Ringo into the ground recording it, you know. I wasn't on 'Maxwell.'” Geoff Emerick continues: “There was a distinct change in the atmosphere after John and Yoko arrived, although personally I felt it had more to do with Lennon being there than his bedridden wife. He was grouchy and moody, and he flatly refused to participate at all in the making of 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer,' which he derisively dismissed as 'just more of Paul's granny music.'”

The first order of business was recording a basic rhythm track using the studio's eight-track equipment, this consisting of George on his Fender Jazz Bass (track one), Ringo on drums (track two), Paul on piano (track three) and Paul's lead vocal (track eight). Sixteen takes were captured on tape, these being numbered 1 through 5 and then 11 through 21. Takes 6 through 10 were either spooled back and recorded over, or the engineer accidentally lost track of his track counting. The first order of business was recording a basic rhythm track using the studio's eight-track equipment, this consisting of George on his Fender Jazz Bass (track one), Ringo on drums (track two), Paul on piano (track three) and Paul's lead vocal (track eight). Sixteen takes were captured on tape, these being numbered 1 through 5 and then 11 through 21. Takes 6 through 10 were either spooled back and recorded over, or the engineer accidentally lost track of his track counting.

The first complete take of the day, "take 5," is included in its entirety on the 1996 released “Anthology 3” album, which shows George playing very proficient bass work. We also witness Paul vocalizing what the future solos might sound like, this sounding quite similar to what singer Harry Nilsson demonstrates vocally on "Pandemonium Shadow Show," this album being deemed a favorite of both McCartney and Lennon. Paul also bluffs his way through some of the lyrics in the third verse, since these hadn't been quite decided upon yet. As this rhythm track concludes on the "Anthology 3" album, we hear a bit of Paul's statments about "nice bits" from the end of "take 12," as detailed below. The first complete take of the day, "take 5," is included in its entirety on the 1996 released “Anthology 3” album, which shows George playing very proficient bass work. We also witness Paul vocalizing what the future solos might sound like, this sounding quite similar to what singer Harry Nilsson demonstrates vocally on "Pandemonium Shadow Show," this album being deemed a favorite of both McCartney and Lennon. Paul also bluffs his way through some of the lyrics in the third verse, since these hadn't been quite decided upon yet. As this rhythm track concludes on the "Anthology 3" album, we hear a bit of Paul's statments about "nice bits" from the end of "take 12," as detailed below.

The complete "take 12," as included on various editions of the "Abbey Road" 50th Anniversary releases, begins with Paul instructing his band-mates about how they should play the song's introduction, although this intro was edited out of the released recording. "Tell you what," Paul tells Ringo, "Do more, sort of a, 'dum dum pa dum a de dum,' you know, a bit..." After Ringo gives it a try, Paul acknowledges, "Yeah, it's just something a bit more, 'cause it does sound a bit dead when you hear it as just an intro." After Ringo demonstrates again, Paul is satisfied, but then moves on to George on bass. He instructs him on the notes he wants his guitarist to play and, after George shows him he has it down, "take 12" begins. This take is nearly identical to "take five" described above, The Beatles doodling around on their instruments after its conclusion. This prompts George Martin to ask from the control room, "How do you feel about it?" The complete "take 12," as included on various editions of the "Abbey Road" 50th Anniversary releases, begins with Paul instructing his band-mates about how they should play the song's introduction, although this intro was edited out of the released recording. "Tell you what," Paul tells Ringo, "Do more, sort of a, 'dum dum pa dum a de dum,' you know, a bit..." After Ringo gives it a try, Paul acknowledges, "Yeah, it's just something a bit more, 'cause it does sound a bit dead when you hear it as just an intro." After Ringo demonstrates again, Paul is satisfied, but then moves on to George on bass. He instructs him on the notes he wants his guitarist to play and, after George shows him he has it down, "take 12" begins. This take is nearly identical to "take five" described above, The Beatles doodling around on their instruments after its conclusion. This prompts George Martin to ask from the control room, "How do you feel about it?"

"One more," Paul answers. "It was good, you know, it had nice bits in it. It would be nice to have the nice bits and the other bits." "And the bad bits," George Harrison adds, prompting McCartney to concur, "And the bad bits, yeah." As George relaxes after these multiple takes, Ringo announces, "George Harrison is resting his arm," Paul adding with a royal decree, "Let it to be known unto the people..." After Ringo laughs, George yells out "KICK OUT THE JAMS..." in reference to the recently released controversial song by MC5. Instead of following this exclamation with "Motherf*ckers" as the original verion of the song includes, Ringo replies by yelling the radio friendly version "BROTHERS AND SISTERS" before performing a snare drum roll. "One more," Paul answers. "It was good, you know, it had nice bits in it. It would be nice to have the nice bits and the other bits." "And the bad bits," George Harrison adds, prompting McCartney to concur, "And the bad bits, yeah." As George relaxes after these multiple takes, Ringo announces, "George Harrison is resting his arm," Paul adding with a royal decree, "Let it to be known unto the people..." After Ringo laughs, George yells out "KICK OUT THE JAMS..." in reference to the recently released controversial song by MC5. Instead of following this exclamation with "Motherf*ckers" as the original verion of the song includes, Ringo replies by yelling the radio friendly version "BROTHERS AND SISTERS" before performing a snare drum roll.

"Take 21" ended up being the rhythm track that was deemed the best, this being set to tape by approximately 8 pm. The rest of the session being used for guitar passage overdubs onto tracks four and five of the eight-track tape, photographic evidence indicating these being played by both Paul and George simultaneously, possibly harmonizing the lead work as heard in various places of the song. By 10:15 pm, the session was closed as The Beatles and the bed-ridden Yoko left for the night. "Take 21" ended up being the rhythm track that was deemed the best, this being set to tape by approximately 8 pm. The rest of the session being used for guitar passage overdubs onto tracks four and five of the eight-track tape, photographic evidence indicating these being played by both Paul and George simultaneously, possibly harmonizing the lead work as heard in various places of the song. By 10:15 pm, the session was closed as The Beatles and the bed-ridden Yoko left for the night.

On the following day, July 10th, 1969, major overdubs were performed on “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” in EMI Studio Two, everyone arriving, including John and Yoko, around 2:30 pm. Paul still wanted an anvil to be hit at strategic places in each chorus, this being recorded on this day on track six (the first chorus) and track seven (the second and third chorus). On the following day, July 10th, 1969, major overdubs were performed on “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” in EMI Studio Two, everyone arriving, including John and Yoko, around 2:30 pm. Paul still wanted an anvil to be hit at strategic places in each chorus, this being recorded on this day on track six (the first chorus) and track seven (the second and third chorus).

“There was no thought given to finding a way to approximate the effect,” Geoff Emerick explains. “Paul wanted the sound of an anvil being struck, so Mal (Evans) was dispatched to track one down...There was a proper blacksmith's anvil brought to the studio for Ringo to hit. They had it rented from a theatrical agency...I have a clear memory of him dragging it into the studio, struggling under its weight as the rest of us laughed our heads off. Both he and Ringo had a go at hitting it. Ringo simply didn't have the strength to lift the hammer, so Mal (Evans) ended up playing the part, but he didn't have a drummer's sense of timing, so it took a while to get a successful take." While Geoff Emerick claims that he was an eyewitness to the events of this day, evidence referred to by Kevin Howlett in his "Track By Track" section of the Super Deluxe edition of "Abbey Road" suggests that Mal Evans was on vacation at the time and thereby couldn't have played the anvil on the recording. Ringo, undoubtedly, performed this task with no problem. “There was no thought given to finding a way to approximate the effect,” Geoff Emerick explains. “Paul wanted the sound of an anvil being struck, so Mal (Evans) was dispatched to track one down...There was a proper blacksmith's anvil brought to the studio for Ringo to hit. They had it rented from a theatrical agency...I have a clear memory of him dragging it into the studio, struggling under its weight as the rest of us laughed our heads off. Both he and Ringo had a go at hitting it. Ringo simply didn't have the strength to lift the hammer, so Mal (Evans) ended up playing the part, but he didn't have a drummer's sense of timing, so it took a while to get a successful take." While Geoff Emerick claims that he was an eyewitness to the events of this day, evidence referred to by Kevin Howlett in his "Track By Track" section of the Super Deluxe edition of "Abbey Road" suggests that Mal Evans was on vacation at the time and thereby couldn't have played the anvil on the recording. Ringo, undoubtedly, performed this task with no problem.

As well as Ringo's anvil playing on the first chorus, overdubs to track six on this day include "Maxwell must go free" harmonies from Paul and George in the third verse as well as piano arpeggios just before the third verse begins. Mark Lewisohn's "The Beatles Recording Sessions" stipulates Paul as performing these piano arpeggios but, in his 2021 Hulu documentary series "McCartney 3,2,1," Paul begs to differ. "I was wondering about the arpeggios because that's a little bit flash for me. Makes me think that was George Martin because, y'know, I can play piano but not that good. If we wanted anything a little bit difficult, George Martin was like our teacher." Onto track seven, other than Ringo's anvil in the second and third chorus, was overdubbed George Martin on Hammond organ, vocal harmonies from Paul and, according to "The Beatles Recording Sessions," George Harrison on electric guitar run through a Leslie speaker. Onto track eight, Paul overdubbed his lead vocals for the third verse since he had just finalized what he wanted these to be, the original lead vocal from the rhythm track, this already being isolated on track eight, being used for the rest of the song. As well as Ringo's anvil playing on the first chorus, overdubs to track six on this day include "Maxwell must go free" harmonies from Paul and George in the third verse as well as piano arpeggios just before the third verse begins. Mark Lewisohn's "The Beatles Recording Sessions" stipulates Paul as performing these piano arpeggios but, in his 2021 Hulu documentary series "McCartney 3,2,1," Paul begs to differ. "I was wondering about the arpeggios because that's a little bit flash for me. Makes me think that was George Martin because, y'know, I can play piano but not that good. If we wanted anything a little bit difficult, George Martin was like our teacher." Onto track seven, other than Ringo's anvil in the second and third chorus, was overdubbed George Martin on Hammond organ, vocal harmonies from Paul and, according to "The Beatles Recording Sessions," George Harrison on electric guitar run through a Leslie speaker. Onto track eight, Paul overdubbed his lead vocals for the third verse since he had just finalized what he wanted these to be, the original lead vocal from the rhythm track, this already being isolated on track eight, being used for the rest of the song.

Another overdub recorded on this day was the "silver hammer man" choral singing by Paul, George and Ringo for the song's conclusion, the higher notes captured on track six, the lower notes on track seven, and a further combination of low and high notes on track eight. “The group were recording the backing vocals for the song,” Geoff Emerick relates about these particular overdubs, “with both George Harrison and Ringo joining Paul at the mic as an impassive John simply sat in the back of the studio and watched them. After a few uncomfortable moments, Paul strode over and invited his old friend and collaborator to join in. I thought it was a nice gesture, an olive branch. But an expressionless Lennon simply said, 'No, I don't think so.' A few minutes later, he and Yoko got up and went home. With nothing to contribute, John just didn't want to be there.” Another overdub recorded on this day was the "silver hammer man" choral singing by Paul, George and Ringo for the song's conclusion, the higher notes captured on track six, the lower notes on track seven, and a further combination of low and high notes on track eight. “The group were recording the backing vocals for the song,” Geoff Emerick relates about these particular overdubs, “with both George Harrison and Ringo joining Paul at the mic as an impassive John simply sat in the back of the studio and watched them. After a few uncomfortable moments, Paul strode over and invited his old friend and collaborator to join in. I thought it was a nice gesture, an olive branch. But an expressionless Lennon simply said, 'No, I don't think so.' A few minutes later, he and Yoko got up and went home. With nothing to contribute, John just didn't want to be there.”

Geoff Emerick continues: “During the first few days they were back, John and Yoko spent most of their time huddled in a corner whispering to each other, or they would go down the hall to the producer's office – the 'green room' – and make phone calls. It didn't come as a huge surprise to me; I just took it as par for the course. At one point George Martin said to me, 'I wish John would get more involved,' but to my knowledge he never did or said anything to try to get the recalcitrant Beatle to participate more. John was definitely very odd by this point, and his involvement in the 'Abbey Road' sessions would be sporadic. For the most part, if we weren't working on one of his songs, he just didn't seem interested.” Geoff Emerick continues: “During the first few days they were back, John and Yoko spent most of their time huddled in a corner whispering to each other, or they would go down the hall to the producer's office – the 'green room' – and make phone calls. It didn't come as a huge surprise to me; I just took it as par for the course. At one point George Martin said to me, 'I wish John would get more involved,' but to my knowledge he never did or said anything to try to get the recalcitrant Beatle to participate more. John was definitely very odd by this point, and his involvement in the 'Abbey Road' sessions would be sporadic. For the most part, if we weren't working on one of his songs, he just didn't seem interested.”

Geoff Emerick writes about Paul overdubbing himself playing bass onto track one, wiping out George's bass performance from the rhythm track in the process. Although documentation doesn't indicate Geoff Emerick's presence in the studio on this day, he relates the following: "There was a good deal of discussion about Paul wanting the Rickenbacker bass on 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' to sound like a tuba, to make the recording sound old-fashioned. We accomplished that by having him articulate the bass like a tuba by sliding into the notes instead of hitting them spot on. A fair amount of time was expended on getting that sound, but Ringo and George Harrison made a point of absenting themselves, so there was no one to raise an objection. At this late stage of the Beatles' career, it seemed that the best way for them to approach making a record - perhaps the only way - was for each band member to work on his own." Paul corroborates this in his "McCartney 3,2,1" documentary, stating: "I think I was trying to get that effect. You play it very short, y'know, don't let the bass ring on...the character of the song is a parody, y'know." Geoff Emerick writes about Paul overdubbing himself playing bass onto track one, wiping out George's bass performance from the rhythm track in the process. Although documentation doesn't indicate Geoff Emerick's presence in the studio on this day, he relates the following: "There was a good deal of discussion about Paul wanting the Rickenbacker bass on 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' to sound like a tuba, to make the recording sound old-fashioned. We accomplished that by having him articulate the bass like a tuba by sliding into the notes instead of hitting them spot on. A fair amount of time was expended on getting that sound, but Ringo and George Harrison made a point of absenting themselves, so there was no one to raise an objection. At this late stage of the Beatles' career, it seemed that the best way for them to approach making a record - perhaps the only way - was for each band member to work on his own." Paul corroborates this in his "McCartney 3,2,1" documentary, stating: "I think I was trying to get that effect. You play it very short, y'know, don't let the bass ring on...the character of the song is a parody, y'know."

After all of the overdubs recorded on this day were complete, George Martin, along with engineers Phil McDonald and John Kurlander, made thirteen attempts at creating a stereo mix of the song, as if they were done recording the song at this point. This was not to be the case, however. At 11:30 pm this session was over.

The next day, July 11th, 1969, The Beatles took to recording some further overdubs onto “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” in EMI Studio Two, the session beginning around 2:30 pm. Onto track six, Paul double-tracked his lead vocals during the second and third choruses while playing acoustic guitar, adding "do-do-do-do" harmonies with George along the way. Attention then went to other “Abbey Road” songs, “Something” and “You Never Give Me Your Money” being added to. This session ended around midnight. The next day, July 11th, 1969, The Beatles took to recording some further overdubs onto “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” in EMI Studio Two, the session beginning around 2:30 pm. Onto track six, Paul double-tracked his lead vocals during the second and third choruses while playing acoustic guitar, adding "do-do-do-do" harmonies with George along the way. Attention then went to other “Abbey Road” songs, “Something” and “You Never Give Me Your Money” being added to. This session ended around midnight.

However, with regards to the other band members, tensions started to mount regarding Paul's intense interest in perfecting “Maxwell's Silver Hammer.” "The worst session ever was 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer,'" Ringo complained to Rolling Stone Magazine in 2008, adding: "It was the worst track we ever had to record. It went on for f*cking weeks. I thought it was mad!" “We'd spend a hell of a lot of time on (it),” George complained, adding: “Paul would always help along when you had done his ten songs. Then, when he got 'round to doing one of my songs, he would help. It was silly. It was very selfish, actually. Sometimes, Paul would make us do these really fruity songs. I mean, my God, 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' was so fruity.” However, with regards to the other band members, tensions started to mount regarding Paul's intense interest in perfecting “Maxwell's Silver Hammer.” "The worst session ever was 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer,'" Ringo complained to Rolling Stone Magazine in 2008, adding: "It was the worst track we ever had to record. It went on for f*cking weeks. I thought it was mad!" “We'd spend a hell of a lot of time on (it),” George complained, adding: “Paul would always help along when you had done his ten songs. Then, when he got 'round to doing one of my songs, he would help. It was silly. It was very selfish, actually. Sometimes, Paul would make us do these really fruity songs. I mean, my God, 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' was so fruity.”

Geoff Emerick relates in his book that Paul "did spend a lot of time working on 'Maxwell,' which irritated George Harrison a bit. One afternoon, they got into a heated argument about it and I started to think, 'Uh-oh, here we go again.' But it died down relatively quickly." Regarding the “Abbey Road” album, Paul relates in the “Anthology” book: “We put together quite a nice album, and the only arguments were about things like me spending too long on a track: I spent three days on 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer.' I remember George saying, 'You've taken three days, it's only a song.' - 'Yeah, but I want to get it right. I've got some thoughts on this one.'...They got annoyed because 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' took three days to record. Big deal!” Geoff Emerick relates in his book that Paul "did spend a lot of time working on 'Maxwell,' which irritated George Harrison a bit. One afternoon, they got into a heated argument about it and I started to think, 'Uh-oh, here we go again.' But it died down relatively quickly." Regarding the “Abbey Road” album, Paul relates in the “Anthology” book: “We put together quite a nice album, and the only arguments were about things like me spending too long on a track: I spent three days on 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer.' I remember George saying, 'You've taken three days, it's only a song.' - 'Yeah, but I want to get it right. I've got some thoughts on this one.'...They got annoyed because 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' took three days to record. Big deal!”

Geoff Emerick, in the book “The Beatles Recording Sessions,” relates: “It's a question of having patience. Paul had it and John didn't. John was always a bit fidgety and restless, wanting to get on, 'yeah, that's good enough, a couple of takes, yeah, that's fine.' But Paul could hear certain refinements in his head which John couldn't." As John stated in 1969 about "Maxwell's Silver Hammer," "We spent more money on that song than any of them on the whole album, I think.” Geoff Emerick, in the book “The Beatles Recording Sessions,” relates: “It's a question of having patience. Paul had it and John didn't. John was always a bit fidgety and restless, wanting to get on, 'yeah, that's good enough, a couple of takes, yeah, that's fine.' But Paul could hear certain refinements in his head which John couldn't." As John stated in 1969 about "Maxwell's Silver Hammer," "We spent more money on that song than any of them on the whole album, I think.”

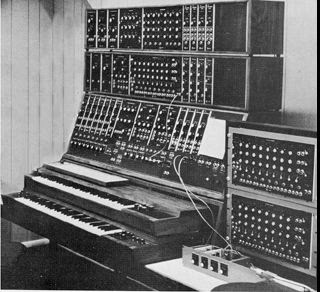

With this tension mounting, attention was given to various other “Abbey Road” songs for nearly a month, August 6th, 1969 being the final recording session to complete “Maxwell's Silver Hammer,” this session beginning at 2:30 and completing by 11 pm. George Harrison's newly acquired Moog synthesizer, a very large and complicated device for its time, was set up in Room 43 at the studios in Abbey Road. Moog synthesizer overdubs onto the song were performed on this day from this room, which were fed into EMI Studio Two. These overdubs were performed simultaneously with reduction mixes from "take 21," six reduction mixes being made with the synthesizer being played for each mix. As Kevin Howlett explains in the "Track by Track" section of the 50th Anniversary "Abbey Road" book, after all of the elements of track six were combined with what was recorded on track seven during the reduction mixes, "three Moog overdubs were played by Paul on tracks four, five and six of 'take 27,'" this being the final reduction mix. With this tension mounting, attention was given to various other “Abbey Road” songs for nearly a month, August 6th, 1969 being the final recording session to complete “Maxwell's Silver Hammer,” this session beginning at 2:30 and completing by 11 pm. George Harrison's newly acquired Moog synthesizer, a very large and complicated device for its time, was set up in Room 43 at the studios in Abbey Road. Moog synthesizer overdubs onto the song were performed on this day from this room, which were fed into EMI Studio Two. These overdubs were performed simultaneously with reduction mixes from "take 21," six reduction mixes being made with the synthesizer being played for each mix. As Kevin Howlett explains in the "Track by Track" section of the 50th Anniversary "Abbey Road" book, after all of the elements of track six were combined with what was recorded on track seven during the reduction mixes, "three Moog overdubs were played by Paul on tracks four, five and six of 'take 27,'" this being the final reduction mix.

In his book "The Lyrics," Paul recollects: "I was very keen on this song, but it took a bit long to record, and the rest of the guys were getting pissed with me. This recording period coincided with the visit to Abbey Road of Robert Moog, the inventor of the Moog synthesizer, and I was fascinated with what could be done with these new sounds. That's one reason why it took a little longer than our normal songs. Not crazy compared to today's standards - it was something like three days (actually four) - but a long time by the standards of the day...Recording sessions were always good because no matter what our personal troubles were, no matter what was happening on the business front, the minute we sat down to make a song we were in good shape. Right until the end there was always a great joy in working together in the studio." In his book "The Lyrics," Paul recollects: "I was very keen on this song, but it took a bit long to record, and the rest of the guys were getting pissed with me. This recording period coincided with the visit to Abbey Road of Robert Moog, the inventor of the Moog synthesizer, and I was fascinated with what could be done with these new sounds. That's one reason why it took a little longer than our normal songs. Not crazy compared to today's standards - it was something like three days (actually four) - but a long time by the standards of the day...Recording sessions were always good because no matter what our personal troubles were, no matter what was happening on the business front, the minute we sat down to make a song we were in good shape. Right until the end there was always a great joy in working together in the studio."

There is some discrepancy in interviews as to who actually played the synthesizer on "Maxwell's Silver Hammer." Describing this song, George related in interview: “It's good because I have this synthesizer and 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' was one of the things I used the synthesizer on, which is pretty effective.” However, engineer Alan Parsons, as interviewed in Andy Babiuk's book "Beatles Gear," especially remembers McCartney's work on the Moog Synthesizer from Room 43 for this song. Also, documentation reveals that, simultaneous to this synthesizer overdub, George was busy in EMI Studio Three overdubbing guitar onto his song "Something." George's statement above was undoubtedly an expression of his recently purchased instrument being used to good effect on this song. There is some discrepancy in interviews as to who actually played the synthesizer on "Maxwell's Silver Hammer." Describing this song, George related in interview: “It's good because I have this synthesizer and 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer' was one of the things I used the synthesizer on, which is pretty effective.” However, engineer Alan Parsons, as interviewed in Andy Babiuk's book "Beatles Gear," especially remembers McCartney's work on the Moog Synthesizer from Room 43 for this song. Also, documentation reveals that, simultaneous to this synthesizer overdub, George was busy in EMI Studio Three overdubbing guitar onto his song "Something." George's statement above was undoubtedly an expression of his recently purchased instrument being used to good effect on this song.

"Paul did 'Maxwell' using the ribbon," 2nd engineer Alan Parsons explains, which was a controller described in the book "Beatles Gear" as "a long strip which induces changes in the sound being played depending on where it is touched and how the player's finger is then moved." Alan Parsons then continues that Paul was "playing it like a violin and having to find every note - which is a credit to Paul's musical ability." In the book "The Beatles Recording Sessions," Alan Parsons also adds: "It's very difficult to find the right notes, rather like a violin, but Paul picked it up straight away. He can pick up anything musical in a couple of days." "Paul did 'Maxwell' using the ribbon," 2nd engineer Alan Parsons explains, which was a controller described in the book "Beatles Gear" as "a long strip which induces changes in the sound being played depending on where it is touched and how the player's finger is then moved." Alan Parsons then continues that Paul was "playing it like a violin and having to find every note - which is a credit to Paul's musical ability." In the book "The Beatles Recording Sessions," Alan Parsons also adds: "It's very difficult to find the right notes, rather like a violin, but Paul picked it up straight away. He can pick up anything musical in a couple of days."

This is especially interesting since, according to the book "Beatles Gear," "you could only sound one note at a time, which was a disadvantage." Upon listening to the Moog playing on "Maxwell's Silver Hammer," one easily notices that three notes are heard at the same time forming chords, such as during the interlude between the first chorus and second verse. Since only one note could be played at a time, this was accomplished during reduction mixes onto another tape, as explained above. This is especially interesting since, according to the book "Beatles Gear," "you could only sound one note at a time, which was a disadvantage." Upon listening to the Moog playing on "Maxwell's Silver Hammer," one easily notices that three notes are heard at the same time forming chords, such as during the interlude between the first chorus and second verse. Since only one note could be played at a time, this was accomplished during reduction mixes onto another tape, as explained above.

After the remixing and synthesizer performances were accomplished on this day, stereo mixes of the song were made in the control room of EMI Studio Two by George Martin and engineers Tony Clark, Phil McDonald and John Kurlander. Ten attempts were made at creating this stereo mix, numbered 14 through 26 (there were no mixes numbered 19 – 21), remix number 18 apparently being deemed the best at the time. “I got involved in the last three weeks of 'Abbey Road,' states engineer Tony Clark in the book “The Beatles Recording History.” “They kept two studios running and I would be asked to sit in studio two or three – usually three – just to be there at the Beatles' beck and call, whenever someone wanted to come in and do an overdub. At this stage of the album I don't think I saw the four of them together.”. After the remixing and synthesizer performances were accomplished on this day, stereo mixes of the song were made in the control room of EMI Studio Two by George Martin and engineers Tony Clark, Phil McDonald and John Kurlander. Ten attempts were made at creating this stereo mix, numbered 14 through 26 (there were no mixes numbered 19 – 21), remix number 18 apparently being deemed the best at the time. “I got involved in the last three weeks of 'Abbey Road,' states engineer Tony Clark in the book “The Beatles Recording History.” “They kept two studios running and I would be asked to sit in studio two or three – usually three – just to be there at the Beatles' beck and call, whenever someone wanted to come in and do an overdub. At this stage of the album I don't think I saw the four of them together.”.

On August 11th, 1969, a mono tape copy of “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” was made of stereo remix 18 for some reason, this being taken away by Mal Evans to be given to Malcolm Davies at Apple for cutting of acetate discs. Paul undoubtedly listened to this mix and deemed it unsuitable, another mix being needed. On August 11th, 1969, a mono tape copy of “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” was made of stereo remix 18 for some reason, this being taken away by Mal Evans to be given to Malcolm Davies at Apple for cutting of acetate discs. Paul undoubtedly listened to this mix and deemed it unsuitable, another mix being needed.

More attempts at a stereo mix of the song were made on August 12th, 1969 by George Martin, Geoff Emerick, Phil McDonald and John Kurlander in the control room of EMI Studio Two, this session beginning at 7 pm with Paul undoubtedly in attendance. Ten more attempts were made, numbered 27 through 36, Paul approving of "take 27" for now. After two other album tracks were stereo mixed as well, this session ended at approximately 2 am the following morning. More attempts at a stereo mix of the song were made on August 12th, 1969 by George Martin, Geoff Emerick, Phil McDonald and John Kurlander in the control room of EMI Studio Two, this session beginning at 7 pm with Paul undoubtedly in attendance. Ten more attempts were made, numbered 27 through 36, Paul approving of "take 27" for now. After two other album tracks were stereo mixed as well, this session ended at approximately 2 am the following morning.

Two days later, on August 14th, 1969, Paul oversaw yet another mixing session to finalize “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” once and for all. This session, which began at 2:30 pm in the control room of EMI Studio Two, consisted of adding an unknown edit piece to the song, which was incorporated from the previous best "take 27" into what was now deemed 'stereo remix 37.' After this was done, among other things, "take 34" from August 12th and "take 37" from this day were edited together to form the released version of the song as we know it. This session ended at 2:30 am the following morning, after many other tracks were worked on as well. Two days later, on August 14th, 1969, Paul oversaw yet another mixing session to finalize “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” once and for all. This session, which began at 2:30 pm in the control room of EMI Studio Two, consisted of adding an unknown edit piece to the song, which was incorporated from the previous best "take 27" into what was now deemed 'stereo remix 37.' After this was done, among other things, "take 34" from August 12th and "take 37" from this day were edited together to form the released version of the song as we know it. This session ended at 2:30 am the following morning, after many other tracks were worked on as well.

At this point, the song had a seven second instrumental introduction which, according to Paul, needed to be done away with. This was done on August 25th, 1969, in the control room of EMI Studio Two between 2:30 and 8 pm.“Maxwell's Silver Hammer” now began precisely when Paul started singing on the first verse. However, Paul had the idea of adding various sound effects to the beginning of the song, this recording being done on this day. In an interview with Rick Beato in August of 2024, Alan Parsons recalls: "We actually tried a backwards delay echo on the intro, which got shelved - didn't work. It was going to go, 'Jo-Jo-Jo-Jo-Jo-Jo-Joan was...,' but nobody liked it." These effects were decided against on this day as well, Paul apparently feeling this was unnecessary after all, the master of the entire album being tape copied and taken away by Geoff Emerick for cutting and release in Britain a month later. At this point, the song had a seven second instrumental introduction which, according to Paul, needed to be done away with. This was done on August 25th, 1969, in the control room of EMI Studio Two between 2:30 and 8 pm.“Maxwell's Silver Hammer” now began precisely when Paul started singing on the first verse. However, Paul had the idea of adding various sound effects to the beginning of the song, this recording being done on this day. In an interview with Rick Beato in August of 2024, Alan Parsons recalls: "We actually tried a backwards delay echo on the intro, which got shelved - didn't work. It was going to go, 'Jo-Jo-Jo-Jo-Jo-Jo-Joan was...,' but nobody liked it." These effects were decided against on this day as well, Paul apparently feeling this was unnecessary after all, the master of the entire album being tape copied and taken away by Geoff Emerick for cutting and release in Britain a month later.

As indicated above, the original "take five," as recorded on July 9th, 1969, was mixed sometime in 1996 by George Martin and Geoff Emerick for release on the compilation album “Anthology 3.” This charming rendition of the song gives a good indication of how it transformed into the released version as we know it. As indicated above, the original "take five," as recorded on July 9th, 1969, was mixed sometime in 1996 by George Martin and Geoff Emerick for release on the compilation album “Anthology 3.” This charming rendition of the song gives a good indication of how it transformed into the released version as we know it.

Sometime between 2004 and 2006, George Martin and his son Giles Martin returned to the master tapes of “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” to isolate Ringo's drums for inclusion in their newly created mash-up mix of “The Fool On The Hill.” This song was not included in the resulting album “Love,” which was created for use with the Cirque du Soleil production of the same name, but was released through iTunes as a bonus track for this collection. Sometime between 2004 and 2006, George Martin and his son Giles Martin returned to the master tapes of “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” to isolate Ringo's drums for inclusion in their newly created mash-up mix of “The Fool On The Hill.” This song was not included in the resulting album “Love,” which was created for use with the Cirque du Soleil production of the same name, but was released through iTunes as a bonus track for this collection.