Search by Keyword

|

"YOU NEVER GIVE ME YOUR MONEY"

(John Lennon – Paul McCartney)

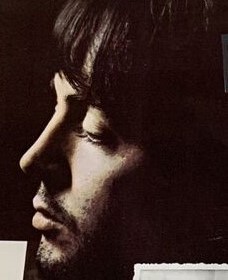

Paul McCartney was not normally in the habit of composing songs that describe specific personal details or actual events occuring in his life. While it can be claimed that the inspirations for various love songs he composed could easily be attributed to whoever was his significant other at that time, these were generally universal in lyrical content, fashioned after the work of popular writers that he admired, such as Gerry Goffin & Carole King and Smokey Robinson. When he was challenged in 1966 to write about something other than romance and/or relationships, Paul tended to construct stories with characters that were created purely out of his imagination. This gave rise to "Paperback Writer," "Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da" and "Rocky Raccoon" among many others. Paul McCartney was not normally in the habit of composing songs that describe specific personal details or actual events occuring in his life. While it can be claimed that the inspirations for various love songs he composed could easily be attributed to whoever was his significant other at that time, these were generally universal in lyrical content, fashioned after the work of popular writers that he admired, such as Gerry Goffin & Carole King and Smokey Robinson. When he was challenged in 1966 to write about something other than romance and/or relationships, Paul tended to construct stories with characters that were created purely out of his imagination. This gave rise to "Paperback Writer," "Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da" and "Rocky Raccoon" among many others.

As for Lennon's output in the later Beatle years, he naturally gravitated to writing about either personal experiences (“I'm So Tired” and “Sexy Sadie”) or tangible motivating factors (“Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite!” and “A Day In The Life”). George Harrison, being immersed in Eastern religion and spirituality in the later '60s, usually made a determined effort to infuse his newly found beliefs into his songs, either literally (like in “Within You Without You” and “The Inner Light”) or masked within the lyrics (“Long, Long, Long” and “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”). As for Lennon's output in the later Beatle years, he naturally gravitated to writing about either personal experiences (“I'm So Tired” and “Sexy Sadie”) or tangible motivating factors (“Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite!” and “A Day In The Life”). George Harrison, being immersed in Eastern religion and spirituality in the later '60s, usually made a determined effort to infuse his newly found beliefs into his songs, either literally (like in “Within You Without You” and “The Inner Light”) or masked within the lyrics (“Long, Long, Long” and “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”).

However, Paul's output in later Beatle years tended to deal more with fantasy. As he relates in the “Beatles Anthology” book: “I remember George once saying to me, 'I couldn't write songs like that.' He writes more from personal experience. John's style was to show the naked truth. If I had been a painter, I would probably mask things a little bit more than some people.” However, Paul's output in later Beatle years tended to deal more with fantasy. As he relates in the “Beatles Anthology” book: “I remember George once saying to me, 'I couldn't write songs like that.' He writes more from personal experience. John's style was to show the naked truth. If I had been a painter, I would probably mask things a little bit more than some people.”

That being said, with the business turmoil The Beatles were going through around the time of April 1969, Paul decided to take a lesson or two from his band-mates and compose a song that at least touched on the specifics of their current state of affairs. The result was “You Never Give Me Your Money.” And while the lyrics are displaying their financial troubles, Paul does proceed to “mask things a little bit.” Just not nearly as much as he usually did. That being said, with the business turmoil The Beatles were going through around the time of April 1969, Paul decided to take a lesson or two from his band-mates and compose a song that at least touched on the specifics of their current state of affairs. The result was “You Never Give Me Your Money.” And while the lyrics are displaying their financial troubles, Paul does proceed to “mask things a little bit.” Just not nearly as much as he usually did.

Songwriting History

"It was written when they were together in New York," states Barry Miles in Paul's biography "Many Years From Now." This undoubtedly refers to the time period of March 19th through April 9th, 1969, Paul spending these three weeks in New York with his new bride Linda, whom he married on March 12th. This would give him time to become more fully acquainted with his new in-laws, as well as to write "You Never Give Me Your Money."

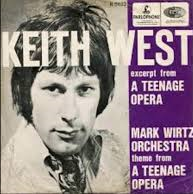

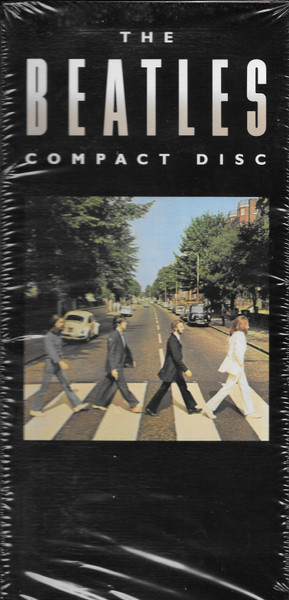

The unique structure of this song, which meanders from one unrelated subject to another without any repeated verses, choruses or refrains (not unlike John's “Happiness Is A Warm Gun”), was different from anything Paul had ever written before, and for good reason. McCartney had quite liked the idea of stringing together different songs into one long medley, Keith West's 1968 release “Excerpt From A Teenage Opera” being cited as a key example. Therefore, with George Martin and the other Beatles eventually on board, Paul started off this project with “You Never Give Me Your Money,” which is actually three different songs connected by appropriate segues. The unique structure of this song, which meanders from one unrelated subject to another without any repeated verses, choruses or refrains (not unlike John's “Happiness Is A Warm Gun”), was different from anything Paul had ever written before, and for good reason. McCartney had quite liked the idea of stringing together different songs into one long medley, Keith West's 1968 release “Excerpt From A Teenage Opera” being cited as a key example. Therefore, with George Martin and the other Beatles eventually on board, Paul started off this project with “You Never Give Me Your Money,” which is actually three different songs connected by appropriate segues.

"I think it was my idea to put all the spare bits together, but I'm a bit wary of claiming these things," Paul explains in the "Beatles Anthology" book. "I'm happy for it to be everyone's idea. Anyway, in the end, we hit upon the idea of medleying them all and giving the second side a sort of operatic structure – which was great because it used ten or twelve unfinished songs in a good way." "I think it was my idea to put all the spare bits together, but I'm a bit wary of claiming these things," Paul explains in the "Beatles Anthology" book. "I'm happy for it to be everyone's idea. Anyway, in the end, we hit upon the idea of medleying them all and giving the second side a sort of operatic structure – which was great because it used ten or twelve unfinished songs in a good way."

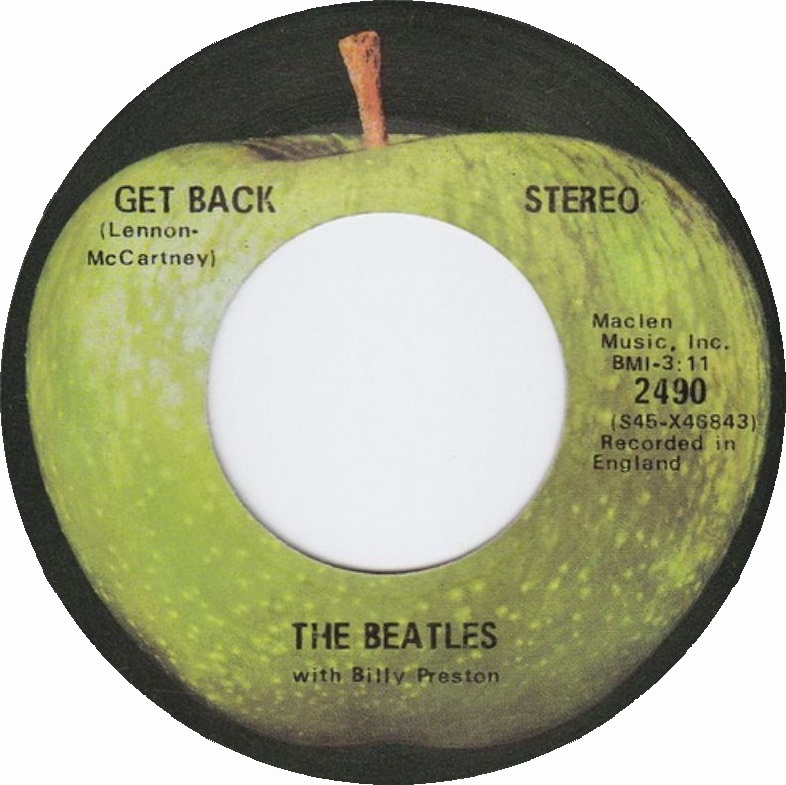

John at first was apparently keen to be a part of this, evidence being a May 1969 interview published in New Musical Express. With the “Get Back” single just released in mid April, John spread the news about the accompanying album, which at this stage was also going to be called "Get Back." “The next Great Beatle Event will be the next LP, in about eight weeks," he explained. "A lot of the tracks will be like 'Get Back,' and a lot of that we did in one take. We've done about twelve tracks; some of them are still to be re-mixed. Also, Paul and I are now working on a kind of song montage that we might do as one piece on one side. We've got two weeks to finish the whole thing, so we're really working at it.” John at first was apparently keen to be a part of this, evidence being a May 1969 interview published in New Musical Express. With the “Get Back” single just released in mid April, John spread the news about the accompanying album, which at this stage was also going to be called "Get Back." “The next Great Beatle Event will be the next LP, in about eight weeks," he explained. "A lot of the tracks will be like 'Get Back,' and a lot of that we did in one take. We've done about twelve tracks; some of them are still to be re-mixed. Also, Paul and I are now working on a kind of song montage that we might do as one piece on one side. We've got two weeks to finish the whole thing, so we're really working at it.”

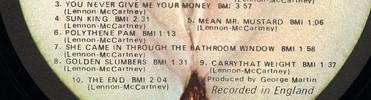

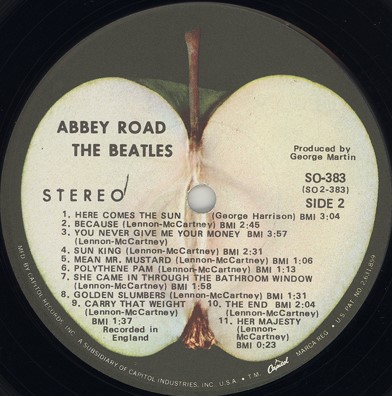

This response suggests that the “song montage” was being considered for what eventually became the “Let It Be” album, which they were hoping to have completed in two weeks from the time of John's statement above, or roughly sometime in June of 1969. Producer Glyn Johns did put together a "Get Back" album on May 28th, 1969 with intentions for a summer release that year, although the "song montage" idea was not included on this proposed album, which never saw a summer 1969 release anyway. Paul had written “You Never Give Me Your Money” for the "song montage" by this time, John having written “Mean Mr. Mustard” and “Polythene Pam” the previous year, but a June deadline for this "montage" was just not feasible. In the meantime, it was in June 1969 that a decision was made to write and record another album, the result becoming “Abbey Road.” This gave the band more time to perfect the “song montage” idea while putting the “Let It Be” sessions on hold for the time being. Sometime later it was decided that they would refurbish the unreleased "Get Back" album mentioned above and release it as a soundtrack album to coincide with the “Let It Be” movie when it premiered in theaters. This response suggests that the “song montage” was being considered for what eventually became the “Let It Be” album, which they were hoping to have completed in two weeks from the time of John's statement above, or roughly sometime in June of 1969. Producer Glyn Johns did put together a "Get Back" album on May 28th, 1969 with intentions for a summer release that year, although the "song montage" idea was not included on this proposed album, which never saw a summer 1969 release anyway. Paul had written “You Never Give Me Your Money” for the "song montage" by this time, John having written “Mean Mr. Mustard” and “Polythene Pam” the previous year, but a June deadline for this "montage" was just not feasible. In the meantime, it was in June 1969 that a decision was made to write and record another album, the result becoming “Abbey Road.” This gave the band more time to perfect the “song montage” idea while putting the “Let It Be” sessions on hold for the time being. Sometime later it was decided that they would refurbish the unreleased "Get Back" album mentioned above and release it as a soundtrack album to coincide with the “Let It Be” movie when it premiered in theaters.

At any rate, Paul's intended purpose for the track “You Never Give Me Your Money” was to begin this long medley. He had a few song ideas (three, in fact) that he hadn't completed as individual songs and strategically strung them together. Regarding the entire “song montage,” Paul explained: “We did it this way because John and I had a number of songs, which were great as they were, but we'd finished them. It often happens that you write the first verse of a song and then you've said it all, and can't be bothered to write a second verse, repeating or giving a variation. So, I said to John, 'Have you got any bits and pieces, which we can make into one long track?' And he had, and we made a piece that makes sense all the way through.” Paul got the ball rolling, so to speak, by himself, stringing together three unfinished songs. At any rate, Paul's intended purpose for the track “You Never Give Me Your Money” was to begin this long medley. He had a few song ideas (three, in fact) that he hadn't completed as individual songs and strategically strung them together. Regarding the entire “song montage,” Paul explained: “We did it this way because John and I had a number of songs, which were great as they were, but we'd finished them. It often happens that you write the first verse of a song and then you've said it all, and can't be bothered to write a second verse, repeating or giving a variation. So, I said to John, 'Have you got any bits and pieces, which we can make into one long track?' And he had, and we made a piece that makes sense all the way through.” Paul got the ball rolling, so to speak, by himself, stringing together three unfinished songs.

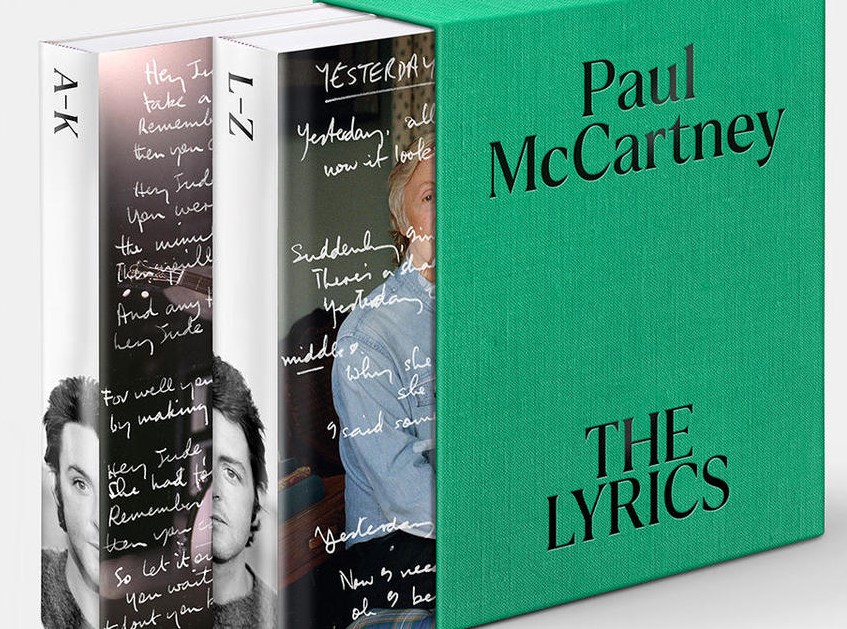

The first unfinished song that is heard is the soft ballad-like piano segment that features the song's title. “This was me directly lambasting Allen Klein's attitude to us,” Paul explains in his book “Many Years From Now,” "no money, just funny paper, all promises and it never works out. It's basically a song about no faith in the person, that found its way into the medley on 'Abbey Road.' John saw the humor in it." In Paul's 2021 book "The Lyrics," Paul relates: "This whole idea of 'funny money' was very much on our minds. Contracts were written on 'funny paper.' Lying behind the song is the idea of the contract as a relationship between two people. The negotiations are at once business negotions and romantic negotiations; I'm thinking of the lines 'And in the middle of negotiations / You break down.' The breakdown in negotiations is also a kind of nervous breakdown." The first unfinished song that is heard is the soft ballad-like piano segment that features the song's title. “This was me directly lambasting Allen Klein's attitude to us,” Paul explains in his book “Many Years From Now,” "no money, just funny paper, all promises and it never works out. It's basically a song about no faith in the person, that found its way into the medley on 'Abbey Road.' John saw the humor in it." In Paul's 2021 book "The Lyrics," Paul relates: "This whole idea of 'funny money' was very much on our minds. Contracts were written on 'funny paper.' Lying behind the song is the idea of the contract as a relationship between two people. The negotiations are at once business negotions and romantic negotiations; I'm thinking of the lines 'And in the middle of negotiations / You break down.' The breakdown in negotiations is also a kind of nervous breakdown."

“That's what we get,” George Harrison concurred at the time. “We get bits of paper, saying how much is earned and what this and that is, but we never actually get it in pounds, shillings and pence. We've all got a big house and a car and an office, but to actually get the money we've earned seems impossible." In an October 1969 interview, George explained: "Whatever you're involved with rubs off and influences you, 'You Never Give Me Your Money' is, I think, all these business meetings that we had to go through to sort out the past...it came out in Paul's song." In his book "The Lyrics," Paul writes: "Allen Klein and Dick James, who sold our publishing in Northern Songs without giving us a chance to buy the company, were both hanging around in the background of this song. All the people who had screwed us or were still trying to screw us. It's fascinating how directly we acknowledged this in the song. We'd cottoned on to them, and they must have cottoned on to the fact that we'd cottoned on. We couldn't have been more direct about it." “That's what we get,” George Harrison concurred at the time. “We get bits of paper, saying how much is earned and what this and that is, but we never actually get it in pounds, shillings and pence. We've all got a big house and a car and an office, but to actually get the money we've earned seems impossible." In an October 1969 interview, George explained: "Whatever you're involved with rubs off and influences you, 'You Never Give Me Your Money' is, I think, all these business meetings that we had to go through to sort out the past...it came out in Paul's song." In his book "The Lyrics," Paul writes: "Allen Klein and Dick James, who sold our publishing in Northern Songs without giving us a chance to buy the company, were both hanging around in the background of this song. All the people who had screwed us or were still trying to screw us. It's fascinating how directly we acknowledged this in the song. We'd cottoned on to them, and they must have cottoned on to the fact that we'd cottoned on. We couldn't have been more direct about it."

Paul continues: "The thing is that we'd grown up as kids with pocket money. Someone gave you a little money at the end of the week, and that's how life worked. We were still a bit like that. When we first got some real money, we were talking to accountants, and they asked us what we were going to do with it. We said we'd put it in the bank. Those were still the days when you could actually make money on the interest on a savings account. But they said, 'No, no, no. That's not what you do. You've got to invest it.' I didn't want to do that, because I considered investment too risky. We knew that property would throw off some money one day, but we didn't really get it." Paul continues: "The thing is that we'd grown up as kids with pocket money. Someone gave you a little money at the end of the week, and that's how life worked. We were still a bit like that. When we first got some real money, we were talking to accountants, and they asked us what we were going to do with it. We said we'd put it in the bank. Those were still the days when you could actually make money on the interest on a savings account. But they said, 'No, no, no. That's not what you do. You've got to invest it.' I didn't want to do that, because I considered investment too risky. We knew that property would throw off some money one day, but we didn't really get it."

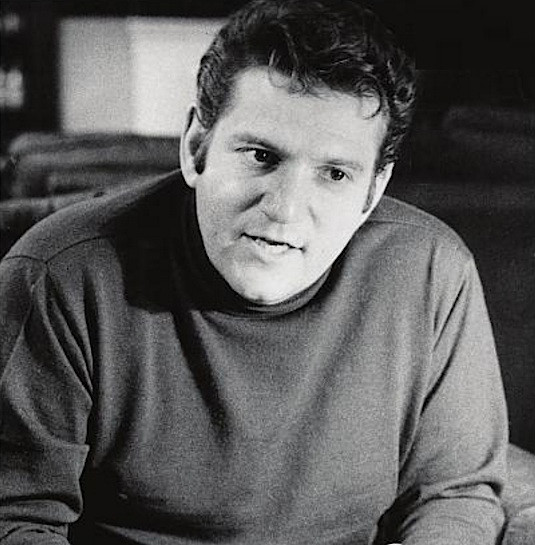

Allen Klein, the celebrated and notorious business manager who had worked with Sam Cooke, The Rolling Stones and many others, was brought in by John to sort out the legal and financial problems facing the group. Paul was resisting getting on board with Allen Klein, his preference for sorting out the group's affairs being his new father-in-law, attorney Lee Eastman. Paul's interaction with Allen Klein during the writing of this section of the song was minimal and/or nonexistent, however McCartney undoubtedly heard claims of what miracles he would be able to do for the group from his band-mates during this time period. "He was a New York spiv who had come over to London," Paul relates in his 2021 book "The Lyrics." "I smelled a rat abut the other chaps didn't, so we had a fight over it and I got voted down. I was trying to be Mr. Rational and Mr. Sensible, and it all went haywire." Allen Klein, the celebrated and notorious business manager who had worked with Sam Cooke, The Rolling Stones and many others, was brought in by John to sort out the legal and financial problems facing the group. Paul was resisting getting on board with Allen Klein, his preference for sorting out the group's affairs being his new father-in-law, attorney Lee Eastman. Paul's interaction with Allen Klein during the writing of this section of the song was minimal and/or nonexistent, however McCartney undoubtedly heard claims of what miracles he would be able to do for the group from his band-mates during this time period. "He was a New York spiv who had come over to London," Paul relates in his 2021 book "The Lyrics." "I smelled a rat abut the other chaps didn't, so we had a fight over it and I got voted down. I was trying to be Mr. Rational and Mr. Sensible, and it all went haywire."

Paul busied himself with other matters at hand, such as recording and mixing sessions, in order to avoid confrontation with Klein. Nonetheless, at a mixing session at Olympic Sound Studios on May 9th, 1969 for the aborted "Get Back" album, three days after the first recording session for “You Never Give Me Your Money,” Klein showed up with an ultimatum on behalf of his company ABKCO taking over the Beatles affairs. Paul refused to comply, which resulted in a major argument and the other three Beatles angrily leaving the session. Therefore, the first section of the song, which had already been written and partially recorded three days before this outburst occurred, must have been directed at what Paul felt would be the results of Allen Klein's taking over the financial affairs of the band, since this hadn't yet occurred. This being the case, Paul's many retrospective quotes about the lryical meaning of this portion of the song being about his many meetings with Allen Klein and the other Beatles are clearly inaccurate. Paul busied himself with other matters at hand, such as recording and mixing sessions, in order to avoid confrontation with Klein. Nonetheless, at a mixing session at Olympic Sound Studios on May 9th, 1969 for the aborted "Get Back" album, three days after the first recording session for “You Never Give Me Your Money,” Klein showed up with an ultimatum on behalf of his company ABKCO taking over the Beatles affairs. Paul refused to comply, which resulted in a major argument and the other three Beatles angrily leaving the session. Therefore, the first section of the song, which had already been written and partially recorded three days before this outburst occurred, must have been directed at what Paul felt would be the results of Allen Klein's taking over the financial affairs of the band, since this hadn't yet occurred. This being the case, Paul's many retrospective quotes about the lryical meaning of this portion of the song being about his many meetings with Allen Klein and the other Beatles are clearly inaccurate.

The second of Paul's unfinished songs, referred to by Paul as "Out Of College...." in a 1969 notebook outlining all of the individual segments of the long medley, is said to be in reference to the exciting uncertainty of the experience The Beatles went through in their formative years. They decided to forgo their education and/or possible careers to throw themselves head-first into what they loved to do, being in a potentially successful 'beat group.' Having “got the sack,” or getting fired, from ordinary jobs they detested anyway, and with almost nothing monetarily to show for themselves, they enveloped themselves in “that magic feeling” of finally acheiving success. The second of Paul's unfinished songs, referred to by Paul as "Out Of College...." in a 1969 notebook outlining all of the individual segments of the long medley, is said to be in reference to the exciting uncertainty of the experience The Beatles went through in their formative years. They decided to forgo their education and/or possible careers to throw themselves head-first into what they loved to do, being in a potentially successful 'beat group.' Having “got the sack,” or getting fired, from ordinary jobs they detested anyway, and with almost nothing monetarily to show for themselves, they enveloped themselves in “that magic feeling” of finally acheiving success.

Interestingly, Paul's original lyric sheet for this segment of the medley ends with the phrase "knowhere to go" with the "k" crossed out. This can easily be assumed to indicate the double meaning of the phrase; it could appear to outsiders that The Beatles had "nowhere to go" after abandoning conventional means of making a living, but they optimistically did "know where to go," which resulted in fame and fortune. Interestingly, Paul's original lyric sheet for this segment of the medley ends with the phrase "knowhere to go" with the "k" crossed out. This can easily be assumed to indicate the double meaning of the phrase; it could appear to outsiders that The Beatles had "nowhere to go" after abandoning conventional means of making a living, but they optimistically did "know where to go," which resulted in fame and fortune.

After a dramatic instrumental segue, we arrive at Paul's third unfinished song, referred to in Paul's above-mentioned notebook as "One Sweet Dream." Barry Miles, in Paul's book “Many Years From Now,” explains this segment as being “a reference to Paul and Linda's trips to purposely get lost in the country.” Paul remembers: "We used to like to escape London, and we'd just drive, going nowhere. We would try to get lost." In Steve Turner's book “A Hard Day's Write,” Linda explains: “As a kid I loved getting lost. I would say to my father, 'Let's get lost.'...Then, when I moved to England to be with Paul (in the Autumn of 1968), we would put Martha in the back of the car and drive out of London. As soon as we were on the open road I'd say, 'Let's get lost,' and we'd keep driving without looking at any signs.” Hence the lyrics, “soon we'll be away from here / step on the gas and wipe that tear away.” Paul also wrote the song “Two Of Us” about these driving experiences with Linda, this song eventually appearing in the “Let It Be” film and soundtrack album. After a dramatic instrumental segue, we arrive at Paul's third unfinished song, referred to in Paul's above-mentioned notebook as "One Sweet Dream." Barry Miles, in Paul's book “Many Years From Now,” explains this segment as being “a reference to Paul and Linda's trips to purposely get lost in the country.” Paul remembers: "We used to like to escape London, and we'd just drive, going nowhere. We would try to get lost." In Steve Turner's book “A Hard Day's Write,” Linda explains: “As a kid I loved getting lost. I would say to my father, 'Let's get lost.'...Then, when I moved to England to be with Paul (in the Autumn of 1968), we would put Martha in the back of the car and drive out of London. As soon as we were on the open road I'd say, 'Let's get lost,' and we'd keep driving without looking at any signs.” Hence the lyrics, “soon we'll be away from here / step on the gas and wipe that tear away.” Paul also wrote the song “Two Of Us” about these driving experiences with Linda, this song eventually appearing in the “Let It Be” film and soundtrack album.

"Paul is always keen to accentuate the positive," author Kevin Howlett explains in his "Track By Track" section of the 50th Anniversary "Abbey Road" liner notes. "Following the despondent opening verses of 'You Never Give Me Your Money,' he had quickly shifted through the gears to reach the elation derived from the exciting possibilities of the open road ahead." In his book "The Lyrics," Paul adds: "There was an upside, however. I'd got married to Linda, and our relationship offered some respite from the dreary infighting and the financial stuff. The lines 'One sweet dream / Pick up the bags, get in the limousine' were a reference to how Linda and I were still able to disappear for a weekend in the country. That saved me." "Paul is always keen to accentuate the positive," author Kevin Howlett explains in his "Track By Track" section of the 50th Anniversary "Abbey Road" liner notes. "Following the despondent opening verses of 'You Never Give Me Your Money,' he had quickly shifted through the gears to reach the elation derived from the exciting possibilities of the open road ahead." In his book "The Lyrics," Paul adds: "There was an upside, however. I'd got married to Linda, and our relationship offered some respite from the dreary infighting and the financial stuff. The lines 'One sweet dream / Pick up the bags, get in the limousine' were a reference to how Linda and I were still able to disappear for a weekend in the country. That saved me."

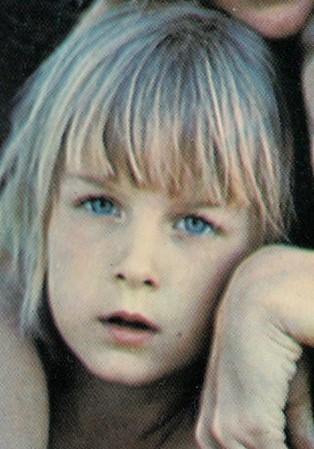

The phrase "one, two, three, four, five, six, seven / all good children go to heaven," which is heard various times during the conclusion of the song, comes from a popular children's jump rope rhyme. The Beatles may have been familiar with this rhyme during their upbringing, or possibly Paul picked it up from Linda's young daughter Heather whom he had recently been in the frequent company of. The entire jump rope rhyme is reportedly as follows: The phrase "one, two, three, four, five, six, seven / all good children go to heaven," which is heard various times during the conclusion of the song, comes from a popular children's jump rope rhyme. The Beatles may have been familiar with this rhyme during their upbringing, or possibly Paul picked it up from Linda's young daughter Heather whom he had recently been in the frequent company of. The entire jump rope rhyme is reportedly as follows:

"One, two, three, four, five, six, seven. All good children go to heaven.

When you get there God will say, 'Where's that book you stole away?'

If you say, 'I don't know,' he will send you down below.

Where everything is red hot peppers!

One, two, three, four five, six, seven. All good children go to heaven.

When you get there, angels say, '(schoolname) children, right this way."

Speaking of his soon-to-be step daughter Heather, Paul also composed a song entitled "Heather," which was contained on a handwritten song list of contenders for the "Abbey Road" album (along with "Get On The Right Thing," which didn't get released until his 1973's "Red Rose Speedway" album). An improvosational version of the song "Heather" was recorded by McCartney and Donovan on November 22nd, 1968 during sessions for Mary Hopkins' album "Postcard." Speaking of his soon-to-be step daughter Heather, Paul also composed a song entitled "Heather," which was contained on a handwritten song list of contenders for the "Abbey Road" album (along with "Get On The Right Thing," which didn't get released until his 1973's "Red Rose Speedway" album). An improvosational version of the song "Heather" was recorded by McCartney and Donovan on November 22nd, 1968 during sessions for Mary Hopkins' album "Postcard."

Olympic Sound Studios, London

Recording History

As mentioned above, Paul brought “You Never Give Me Your Money” into the recording studio for the first time on May 6th, 1969. This was at London's Olympic Sound Studios, undoubtedly because EMI Studios were unavailable, the sessions beginning at 3 pm. George Martin was recruited as producer of the session with Glyn Johns, who had been overseeing the January "Get Back" sessions, as engineer. Documentation shows the song being called "You Never Give Me Your Money - Part I" at this point, undoubtedly because of it already being considered as the opening segment of the proposed "song montage." This was, in fact, the very first recording session for the "Abbey Road" side two medley.

A total of 36 takes of the song were recorded on this day, a good amount of time being taken for Paul to aquaint the other Beatles with the framework of all three sections of the song and in working out the arrangement. The instrumentation of these takes consisted of Paul on guide vocal (track one) and piano (track two), Ringo's drums (track three), John on distorted electric guitar (track five) and George on "bassy guitar," as the Olympic tape box called it (track six). The lower-toned notes George played during the opening section of the song were indeed "bassy," his guitar work being developed as the takes progressed. "I'm playing a harmony of what you're doing," he informed Paul after "take 17." A total of 36 takes of the song were recorded on this day, a good amount of time being taken for Paul to aquaint the other Beatles with the framework of all three sections of the song and in working out the arrangement. The instrumentation of these takes consisted of Paul on guide vocal (track one) and piano (track two), Ringo's drums (track three), John on distorted electric guitar (track five) and George on "bassy guitar," as the Olympic tape box called it (track six). The lower-toned notes George played during the opening section of the song were indeed "bassy," his guitar work being developed as the takes progressed. "I'm playing a harmony of what you're doing," he informed Paul after "take 17."

Interestingly, Paul's piano was fed through a rotating Leslie speaker from the point in the song where the lyrics "Oh, that magic feeling" occur, Glyn Johns apparently in charge of activating the speaker at that time to run through to the end of the song. Before beginning several of the takes recorded on this day, Paul had to remind Glyn, "Leslie off, please." The original idea of ending the song was abrupt, as evidenced in many of the early takes concluding just before where the "one, two, three, four, five, six, seven" vocals would eventually be added. As the evening progressed, however, a decision was made to mess about at the end of the takes, the band concluding that it would be faded out or edited off as a segue into a further feature of the medley. Interestingly, Paul's piano was fed through a rotating Leslie speaker from the point in the song where the lyrics "Oh, that magic feeling" occur, Glyn Johns apparently in charge of activating the speaker at that time to run through to the end of the song. Before beginning several of the takes recorded on this day, Paul had to remind Glyn, "Leslie off, please." The original idea of ending the song was abrupt, as evidenced in many of the early takes concluding just before where the "one, two, three, four, five, six, seven" vocals would eventually be added. As the evening progressed, however, a decision was made to mess about at the end of the takes, the band concluding that it would be faded out or edited off as a segue into a further feature of the medley.

The final take of the night, "take 36," is featured in various 50th Anniversary "Abbey Road" releases. Before the take begins, Paul, George and John rehearse their parts while Paul states in the microphone, eventually adopting a low voice in imitation of a smarmy lounge singer, "OK, alright, you win, I'm in love with you...OK, you win, I'm in love with you, well alright, OK-yay." He then clears his throat, sings the song's title in a falsetto voice, and then mumbles in a low voice "Walnetto sandwich" in imitation of the late Arte Johnson's character "Tyrone F. Horneigh" from the then-popular television show "Rowan & Martin's Laugh In." The final take of the night, "take 36," is featured in various 50th Anniversary "Abbey Road" releases. Before the take begins, Paul, George and John rehearse their parts while Paul states in the microphone, eventually adopting a low voice in imitation of a smarmy lounge singer, "OK, alright, you win, I'm in love with you...OK, you win, I'm in love with you, well alright, OK-yay." He then clears his throat, sings the song's title in a falsetto voice, and then mumbles in a low voice "Walnetto sandwich" in imitation of the late Arte Johnson's character "Tyrone F. Horneigh" from the then-popular television show "Rowan & Martin's Laugh In."

After Paul humorously sings, "You never give me your coffee," he rallies his bandmates together by rattling off, "OK, come on lads, here it is boys, here it is, come on boys." He tests out his piano to see that the Leslie effect is still on, which promps George to yell out "Leslie off" off microphone, and prompts Paul to also instruct Glyn Johns "Leslie off, please." Paul then indicates the need to get the perfect take accomplished by saying, "It's exactly half-past two and it's '36' and here we go!" After George Martin repeats "36" and a short pause ensues, the final complete take then begins. This excellent complete take concluded with some extended jamming which was faded off on the mix included on the above mentioned "Abbey Road" releases. After Paul humorously sings, "You never give me your coffee," he rallies his bandmates together by rattling off, "OK, come on lads, here it is boys, here it is, come on boys." He tests out his piano to see that the Leslie effect is still on, which promps George to yell out "Leslie off" off microphone, and prompts Paul to also instruct Glyn Johns "Leslie off, please." Paul then indicates the need to get the perfect take accomplished by saying, "It's exactly half-past two and it's '36' and here we go!" After George Martin repeats "36" and a short pause ensues, the final complete take then begins. This excellent complete take concluded with some extended jamming which was faded off on the mix included on the above mentioned "Abbey Road" releases.

In the end, however, "take 30" was decided to be the keeper, this including Paul exclaiming "bloody hell" as the song was winding down as faintly heard in the released version (at the 3:52 mark of the song). This take also included extended jamming which eventually brought the song into double-time on the drums with John playing a standard 12-bar rhythm on electric guitar before it finally ground to a halt, this being evidenced in bootleg recordings. This, of course, would be faded out in the mixing stage, which meant that they had to come up with another way of bringing in the next feature of the medley. This would be worked out later. A quick stereo mix of the song as it was so far was created at the end of the session by producer George Martin and engineers Glyn Johns and Steve Vaughan. Without doubt, this stereo mix was taken away by Paul to decide what was next needed to complete this section of the medley. By 4 am the following morning, The Beatles retired for the night. In the end, however, "take 30" was decided to be the keeper, this including Paul exclaiming "bloody hell" as the song was winding down as faintly heard in the released version (at the 3:52 mark of the song). This take also included extended jamming which eventually brought the song into double-time on the drums with John playing a standard 12-bar rhythm on electric guitar before it finally ground to a halt, this being evidenced in bootleg recordings. This, of course, would be faded out in the mixing stage, which meant that they had to come up with another way of bringing in the next feature of the medley. This would be worked out later. A quick stereo mix of the song as it was so far was created at the end of the session by producer George Martin and engineers Glyn Johns and Steve Vaughan. Without doubt, this stereo mix was taken away by Paul to decide what was next needed to complete this section of the medley. By 4 am the following morning, The Beatles retired for the night.

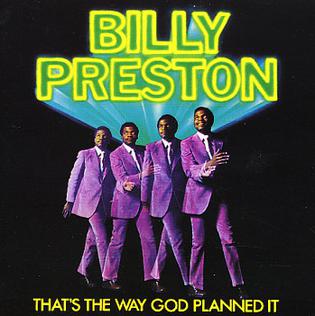

Contrary to what John excitedly revealed to New Musical Express in early May about their working quickly to release their new album by mid 1969, a change in plans occurred. On May 15th, Paul informed BBC Radio in an interview: "We've got nothing on for the next month and we've had a lot on for the past couple of months, as you might have heard from a couple of newspapers, it's been high finance. But it seems to be going OK now, so I'm just taking a break to get away from it all." During the break, John and Yoko staged a Bed-In for Peace in Montreal, Canada, George produced the Billy Preston album "That's The Way God Planned It," and Paul and Ringo both took time out for vacations. They did, however, book extensive sessions at EMI Studios throughout most of July and August to reconvene for recording a newly imagined album to be released later in the year. They all just needed a break to clear their heads. Contrary to what John excitedly revealed to New Musical Express in early May about their working quickly to release their new album by mid 1969, a change in plans occurred. On May 15th, Paul informed BBC Radio in an interview: "We've got nothing on for the next month and we've had a lot on for the past couple of months, as you might have heard from a couple of newspapers, it's been high finance. But it seems to be going OK now, so I'm just taking a break to get away from it all." During the break, John and Yoko staged a Bed-In for Peace in Montreal, Canada, George produced the Billy Preston album "That's The Way God Planned It," and Paul and Ringo both took time out for vacations. They did, however, book extensive sessions at EMI Studios throughout most of July and August to reconvene for recording a newly imagined album to be released later in the year. They all just needed a break to clear their heads.

Once they reconvened to record this new album, which was on July 1st, 1969 at EMI Studio Two at 3 pm, the first thing on the agenda was continuing work on the medley, “You Never Give Me Your Money” being the only song of the medley they had worked on thus far. With John hospitalized at the time because of a recent automobile accident in Scotland, it appears that it was Paul alone that arrived at EMI Studio Two on this day to add new lead vocals onto track one of 'take 30' of the song, recording over his guide vocals in the process. With this accomplished to Paul's satisfaction, the session ended at around 7:30 pm. Once they reconvened to record this new album, which was on July 1st, 1969 at EMI Studio Two at 3 pm, the first thing on the agenda was continuing work on the medley, “You Never Give Me Your Money” being the only song of the medley they had worked on thus far. With John hospitalized at the time because of a recent automobile accident in Scotland, it appears that it was Paul alone that arrived at EMI Studio Two on this day to add new lead vocals onto track one of 'take 30' of the song, recording over his guide vocals in the process. With this accomplished to Paul's satisfaction, the session ended at around 7:30 pm.

The Beatles blocked out studio time in EMI Studios for nearly every day of July and August of 1969 for serious work on their final album, which eventually would be titled “Abbey Road.” With many other songs being started within the following nine days, including more songs for the long medley, work resumed on “You Never Give Me Your Money” on July 11th, 1969. The Beatles arrived in EMI Studio Two at 2:30 pm on this day and, after working on “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” and “Something,” Paul added a bass guitar overdub onto track seven of “You Never Give Me Your Money.” This session concluded at midnight. The Beatles blocked out studio time in EMI Studios for nearly every day of July and August of 1969 for serious work on their final album, which eventually would be titled “Abbey Road.” With many other songs being started within the following nine days, including more songs for the long medley, work resumed on “You Never Give Me Your Money” on July 11th, 1969. The Beatles arrived in EMI Studio Two at 2:30 pm on this day and, after working on “Maxwell's Silver Hammer” and “Something,” Paul added a bass guitar overdub onto track seven of “You Never Give Me Your Money.” This session concluded at midnight.

After the weekend, The Beatles resumed work on the song in EMI Studio Three on July 15th, 1969, the session beginning at 2:30 pm. By 6 pm, Paul double-tracked his vocals in certain areas of the song, and also played tubular bells (as also heard during the "fireman" references in "Penny Lane"), which were designated on the recording sheet as "Studio Chimes Used." These chimes were played to augment John's guitar arpeggios during the instrumental section that closes the song, all of this recorded onto track four of the tape. It may also be on this day that George double-tracked his extensive lead guitar passage in the elaborate seque between the "Out Of College" and "One Sweet Dream" sections of the song. From 6 to 11 pm, George Martin and engineers Phil McDonald and Alan Parsons worked at creating yet another stereo mix of the song, as it was so far, for Paul to review. Six attempts at this mix were made, only three of them making their way to the end of the song. The session then ended at around 11 pm. After the weekend, The Beatles resumed work on the song in EMI Studio Three on July 15th, 1969, the session beginning at 2:30 pm. By 6 pm, Paul double-tracked his vocals in certain areas of the song, and also played tubular bells (as also heard during the "fireman" references in "Penny Lane"), which were designated on the recording sheet as "Studio Chimes Used." These chimes were played to augment John's guitar arpeggios during the instrumental section that closes the song, all of this recorded onto track four of the tape. It may also be on this day that George double-tracked his extensive lead guitar passage in the elaborate seque between the "Out Of College" and "One Sweet Dream" sections of the song. From 6 to 11 pm, George Martin and engineers Phil McDonald and Alan Parsons worked at creating yet another stereo mix of the song, as it was so far, for Paul to review. Six attempts at this mix were made, only three of them making their way to the end of the song. The session then ended at around 11 pm.

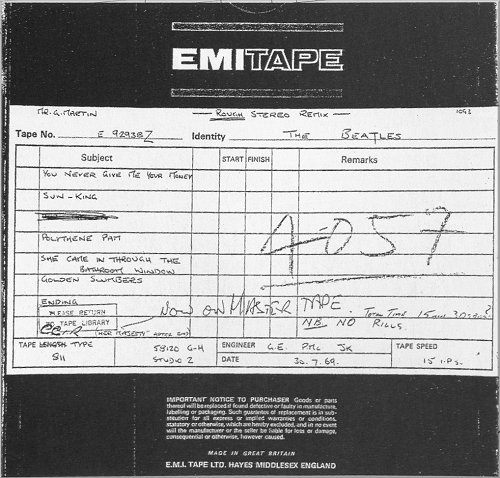

The song was then set aside for two weeks while work on various other “Abbey Road” tracks was being focused on, including the remaining segments of the medley. Then, on July 30th, 1969, it was decided to do a trial run at piecing together all of the medley songs into one cohesive unit. Some of the songs to be used in the medley weren't completely finished - no vocals had been recorded yet for the song “The End,” for example - but they wanted to experiment on how it could be accomplished. The song was then set aside for two weeks while work on various other “Abbey Road” tracks was being focused on, including the remaining segments of the medley. Then, on July 30th, 1969, it was decided to do a trial run at piecing together all of the medley songs into one cohesive unit. Some of the songs to be used in the medley weren't completely finished - no vocals had been recorded yet for the song “The End,” for example - but they wanted to experiment on how it could be accomplished.

The Beatles entered the control room of EMI Studio Two at 2 pm on this day, the first order of business being the first song in this medley, namely “You Never Give Me Your Money.” First on the agenda was making a tape reduction of the song, six attempts being made thereof ("take 37" through "take 42"), "take 40" being deemed best. After this was complete at 3:30 pm, they moved over to EMI Studio Three to record some needed elements for some of the medley songs. Onto track eight of what was then called "take 40" of “You Never Give Me Your Money,” backing vocals were overdubbed by John, Paul and George in various parts of the song, including the "one, two, three, four, five, six, seven..." harmonies during its conclusion, accentuated by Ringo with a tambourine at the end of each vocal phrase. After overdubs were also recorded onto other medley songs, they moved back into the control room of EMI Studio Two at 10:30 pm to actually try to assemble the medley. The Beatles entered the control room of EMI Studio Two at 2 pm on this day, the first order of business being the first song in this medley, namely “You Never Give Me Your Money.” First on the agenda was making a tape reduction of the song, six attempts being made thereof ("take 37" through "take 42"), "take 40" being deemed best. After this was complete at 3:30 pm, they moved over to EMI Studio Three to record some needed elements for some of the medley songs. Onto track eight of what was then called "take 40" of “You Never Give Me Your Money,” backing vocals were overdubbed by John, Paul and George in various parts of the song, including the "one, two, three, four, five, six, seven..." harmonies during its conclusion, accentuated by Ringo with a tambourine at the end of each vocal phrase. After overdubs were also recorded onto other medley songs, they moved back into the control room of EMI Studio Two at 10:30 pm to actually try to assemble the medley.

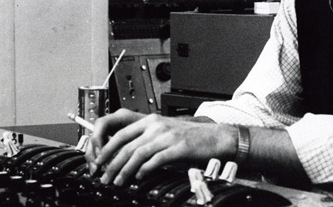

Before this could be done, however, preliminary stereo mixes of all the songs that were to become part of the medley needed to be created. These stereo mixes were created by George Martin and engineers Geoff Emerick, Phil McDonald and John Kurlander. With all this accomplished, the editing, crossfading and tape compilation of all of these songs began. Photographic evidence from this time period shows Paul working the faders on the control panel, indicating that he played an intrinsic part in editing this medley together. Before this could be done, however, preliminary stereo mixes of all the songs that were to become part of the medley needed to be created. These stereo mixes were created by George Martin and engineers Geoff Emerick, Phil McDonald and John Kurlander. With all this accomplished, the editing, crossfading and tape compilation of all of these songs began. Photographic evidence from this time period shows Paul working the faders on the control panel, indicating that he played an intrinsic part in editing this medley together.

Engineer Geoff Emerick, in his book “Here, There And Everywhere,” relates the events of this evening: “The medley was now nearly complete, and it was decided to do a test edit to see how all the various components fit together. That session was a long one – for the first time since the 'White Album' days, we worked late into the night – but everyone was really upbeat and quite pleased with the results. There was only one little bit of contention, and it had to do with the cross-fade between 'You Never Give Me Your Money' and '...Sun King.' John didn't like the idea of there being such a long gap between the two songs, but Paul felt strongly that the mood needed to be set for the listener before 'Sun King' started. In the end, Paul got his way – John merely shrugged his shoulders and feigned disinterest. At first, a single held organ note was used for the crossfade.” Engineer Geoff Emerick, in his book “Here, There And Everywhere,” relates the events of this evening: “The medley was now nearly complete, and it was decided to do a test edit to see how all the various components fit together. That session was a long one – for the first time since the 'White Album' days, we worked late into the night – but everyone was really upbeat and quite pleased with the results. There was only one little bit of contention, and it had to do with the cross-fade between 'You Never Give Me Your Money' and '...Sun King.' John didn't like the idea of there being such a long gap between the two songs, but Paul felt strongly that the mood needed to be set for the listener before 'Sun King' started. In the end, Paul got his way – John merely shrugged his shoulders and feigned disinterest. At first, a single held organ note was used for the crossfade.”

This trial run at editing together all of the segments of the medley, as accomplished on July 30th, 1969, is included in various 50th Anniversary editions of "Abbey Road" under the title "The Long One (Trial Edit & Mix - 30 July 1969)." Interesing differences heard on this mix of "You Never Give Me Your Money," which was taken directly from "take 40," include the presence of Paul's Leslie piano in the later half of the song, which was faded down in the released version, and backing harmonies from John, Paul and George during the "Out Of College" segment. The song fades down somewhat earlier than we're used to hearing, and we hear the organ chord (not a "single held organ note" as Geoff Emerick stated) used as a segue between the songs, this being an E major organ chord to transition from A major of the first song to E major of "Sun King." Everyone was pleased with how the trial edit came out, with the exception of the inclusion of "Her Majesty," which was omited when the final edit was created. This brought the session to a close at 2:30 am the following morning. This trial run at editing together all of the segments of the medley, as accomplished on July 30th, 1969, is included in various 50th Anniversary editions of "Abbey Road" under the title "The Long One (Trial Edit & Mix - 30 July 1969)." Interesing differences heard on this mix of "You Never Give Me Your Money," which was taken directly from "take 40," include the presence of Paul's Leslie piano in the later half of the song, which was faded down in the released version, and backing harmonies from John, Paul and George during the "Out Of College" segment. The song fades down somewhat earlier than we're used to hearing, and we hear the organ chord (not a "single held organ note" as Geoff Emerick stated) used as a segue between the songs, this being an E major organ chord to transition from A major of the first song to E major of "Sun King." Everyone was pleased with how the trial edit came out, with the exception of the inclusion of "Her Majesty," which was omited when the final edit was created. This brought the session to a close at 2:30 am the following morning.

The next day, July 31st, 1969, saw The Beatles continue work on “You Never Give Me Your Money.” They entered EMI Studio Two at 2:30 pm with Paul having definite ideas for additional overdubs for the song. After Paul heard "take 40" of the song, which was the most recent mix made the day before during the experimental medley editing session, he deemed the reduction mix that was done on that day unnecessary. This meant that the backing vocal overdubs that were done after that reduction mix would either need to be re-recorded or eliminated altogether. The overdubs he now wanted to perform on this day would be recorded onto the original edited "take 30." The next day, July 31st, 1969, saw The Beatles continue work on “You Never Give Me Your Money.” They entered EMI Studio Two at 2:30 pm with Paul having definite ideas for additional overdubs for the song. After Paul heard "take 40" of the song, which was the most recent mix made the day before during the experimental medley editing session, he deemed the reduction mix that was done on that day unnecessary. This meant that the backing vocal overdubs that were done after that reduction mix would either need to be re-recorded or eliminated altogether. The overdubs he now wanted to perform on this day would be recorded onto the original edited "take 30."

Onto track seven of "take 30," Paul re-recorded his bass part on top of his previous attempt from July 15th, figuring he could do a better job. With this done, Paul also felt the song needed more piano work, not being entirely happy with the effect of his piano being run through a Leslie speaker in the second half of the original rhythm track. Instead, starting from the "Out Of College" segment of the song, he recorded what was documented as "jangle piano," which Paul played on piano at half-speed to give a "honky-tonk" effect when played at the correct speed. The backing harmonies of John, Paul and George were also re-recorded during the opening segment of the song as well as during the conclusion of the "Out Of College" segment after the final lyric "know where to go." With all of this complete, they focused on adding more overdubs to the “Golden Slumbers / Carry That Weight” portion of the medley, which then brought the session to a conclusion at 1:15 am the following morning. Onto track seven of "take 30," Paul re-recorded his bass part on top of his previous attempt from July 15th, figuring he could do a better job. With this done, Paul also felt the song needed more piano work, not being entirely happy with the effect of his piano being run through a Leslie speaker in the second half of the original rhythm track. Instead, starting from the "Out Of College" segment of the song, he recorded what was documented as "jangle piano," which Paul played on piano at half-speed to give a "honky-tonk" effect when played at the correct speed. The backing harmonies of John, Paul and George were also re-recorded during the opening segment of the song as well as during the conclusion of the "Out Of College" segment after the final lyric "know where to go." With all of this complete, they focused on adding more overdubs to the “Golden Slumbers / Carry That Weight” portion of the medley, which then brought the session to a conclusion at 1:15 am the following morning.

Still, the dilemma of how to segue “You Never Give Me Your Money” into “Sun King” weighed on Paul's mind. Then, he came up with a solution. Mark Lewisohn, in his book “The Beatles Recording Sessions,” relates: “Paul McCartney, in particular, would still spend spare time in the sound equipment room of his St. John's Wood house, making tape loops (with his Brennell tape machine). On this day, 5 August 1969, Paul took a plastic bag containing a dozen loose strands of mono tape into (EMI Studios), where – together with the production staff – he spent the afternoon in the studio three control room transferring the best of these onto professional four-track tape. The effects – sounding like bells, birds, bubbles and crickets chirping – allowed for a perfect crossfade in the medley.” Geoff Emerick concurs: “Paul arrived with a plastic bag of tape loops (just as he had done when we worked on 'Tomorrow Never Knows' years before) and we used several of them.” Still, the dilemma of how to segue “You Never Give Me Your Money” into “Sun King” weighed on Paul's mind. Then, he came up with a solution. Mark Lewisohn, in his book “The Beatles Recording Sessions,” relates: “Paul McCartney, in particular, would still spend spare time in the sound equipment room of his St. John's Wood house, making tape loops (with his Brennell tape machine). On this day, 5 August 1969, Paul took a plastic bag containing a dozen loose strands of mono tape into (EMI Studios), where – together with the production staff – he spent the afternoon in the studio three control room transferring the best of these onto professional four-track tape. The effects – sounding like bells, birds, bubbles and crickets chirping – allowed for a perfect crossfade in the medley.” Geoff Emerick concurs: “Paul arrived with a plastic bag of tape loops (just as he had done when we worked on 'Tomorrow Never Knows' years before) and we used several of them.”

This occurred on August 5th, 1969 in the control room of EMI Studio Three, the composite sound effects tape being assembled between 2:30 and 6:30 pm. The tape box documentation shows that Paul's loops were recorded onto a four-track machine, consisting of all the loops recorded together on track one, sped up backwards electric guitars on track two, moans and various voices on track three, and voices, bells and crickets from an EMI sound effects tape on track four. Five 'takes' of compiling these sound effects were made, a 1:23 section of "take five" (between 6:28 and 7:51) being deemed suitable for using as a segue between the two songs. It appears, however, that the bells and crickets were the only effects making the grade for the finished record. This occurred on August 5th, 1969 in the control room of EMI Studio Three, the composite sound effects tape being assembled between 2:30 and 6:30 pm. The tape box documentation shows that Paul's loops were recorded onto a four-track machine, consisting of all the loops recorded together on track one, sped up backwards electric guitars on track two, moans and various voices on track three, and voices, bells and crickets from an EMI sound effects tape on track four. Five 'takes' of compiling these sound effects were made, a 1:23 section of "take five" (between 6:28 and 7:51) being deemed suitable for using as a segue between the two songs. It appears, however, that the bells and crickets were the only effects making the grade for the finished record.

Then, with the above-mentioned overdubs onto "take 30" of the song accomplished, more attempts at creating a stereo mix were made on August 13th, 1969 in the control room of EMI Studio Two between 2:30 and 9:15 pm. It was decided, however, that this final stereo mix would be an edit of "take 30" of the original master tape with the ending of the "take 40" tape reduction made on July 30th, this including the "one, two, three, four, five, six, seven" harmony phrases. George Martin and engineers Geoff Emerick, Phil McDonald and Alan Parsons made eight attempts at this edit and stereo mix, numbered 20 through 27, working hard to mix out certain awkward lead guitar runs in the final moments of the song played by George Harrison on the original rhythm track, as well as a couple unneeded vocalizations from Paul and the first occurance of the "one, two, three, four, five" harmony phrase, which was now deemed undesirable. The edit occurs directly after Paul's vocalization "came true today, yes it did" and just before his ad libbed "ah, ah, ah..." line. In the end, remix 23 was considered the best. Then, with the above-mentioned overdubs onto "take 30" of the song accomplished, more attempts at creating a stereo mix were made on August 13th, 1969 in the control room of EMI Studio Two between 2:30 and 9:15 pm. It was decided, however, that this final stereo mix would be an edit of "take 30" of the original master tape with the ending of the "take 40" tape reduction made on July 30th, this including the "one, two, three, four, five, six, seven" harmony phrases. George Martin and engineers Geoff Emerick, Phil McDonald and Alan Parsons made eight attempts at this edit and stereo mix, numbered 20 through 27, working hard to mix out certain awkward lead guitar runs in the final moments of the song played by George Harrison on the original rhythm track, as well as a couple unneeded vocalizations from Paul and the first occurance of the "one, two, three, four, five" harmony phrase, which was now deemed undesirable. The edit occurs directly after Paul's vocalization "came true today, yes it did" and just before his ad libbed "ah, ah, ah..." line. In the end, remix 23 was considered the best.

The following day, August 14th, 1969, saw the same engineering staff, with The Beatles input no doubt, remixing, crossfading and editing the now finished songs for the medley. This twelve-hour session occurred in the EMI Studio Two control room from 2:30 pm to 2:30 am the following morning. Eleven attempts were made at crossfading “You Never Give Me Your Money” with “Sun King” utilizing Paul's sound effects tape. They thought they had achieved the perfect crossfade by the end of the session. The following day, August 14th, 1969, saw the same engineering staff, with The Beatles input no doubt, remixing, crossfading and editing the now finished songs for the medley. This twelve-hour session occurred in the EMI Studio Two control room from 2:30 pm to 2:30 am the following morning. Eleven attempts were made at crossfading “You Never Give Me Your Money” with “Sun King” utilizing Paul's sound effects tape. They thought they had achieved the perfect crossfade by the end of the session.

But they were not quite satisfied. On August 21st, 1969, in the control room of EMI Studio Two, one final attempt was made of creating the perfect crossfade between the two songs with Paul's sound effects tape. The session began at 2:30 pm and, lo and behold, they finally got it to everyone's satisfaction, including Paul and George Martin. The finished master for the “Abbey Road” album was made the day before, so this new stereo mix needed to be inserted into the finished master, along with a new remix of the song “The End” which was also made on this day. By midnight, this session was complete. But they were not quite satisfied. On August 21st, 1969, in the control room of EMI Studio Two, one final attempt was made of creating the perfect crossfade between the two songs with Paul's sound effects tape. The session began at 2:30 pm and, lo and behold, they finally got it to everyone's satisfaction, including Paul and George Martin. The finished master for the “Abbey Road” album was made the day before, so this new stereo mix needed to be inserted into the finished master, along with a new remix of the song “The End” which was also made on this day. By midnight, this session was complete.

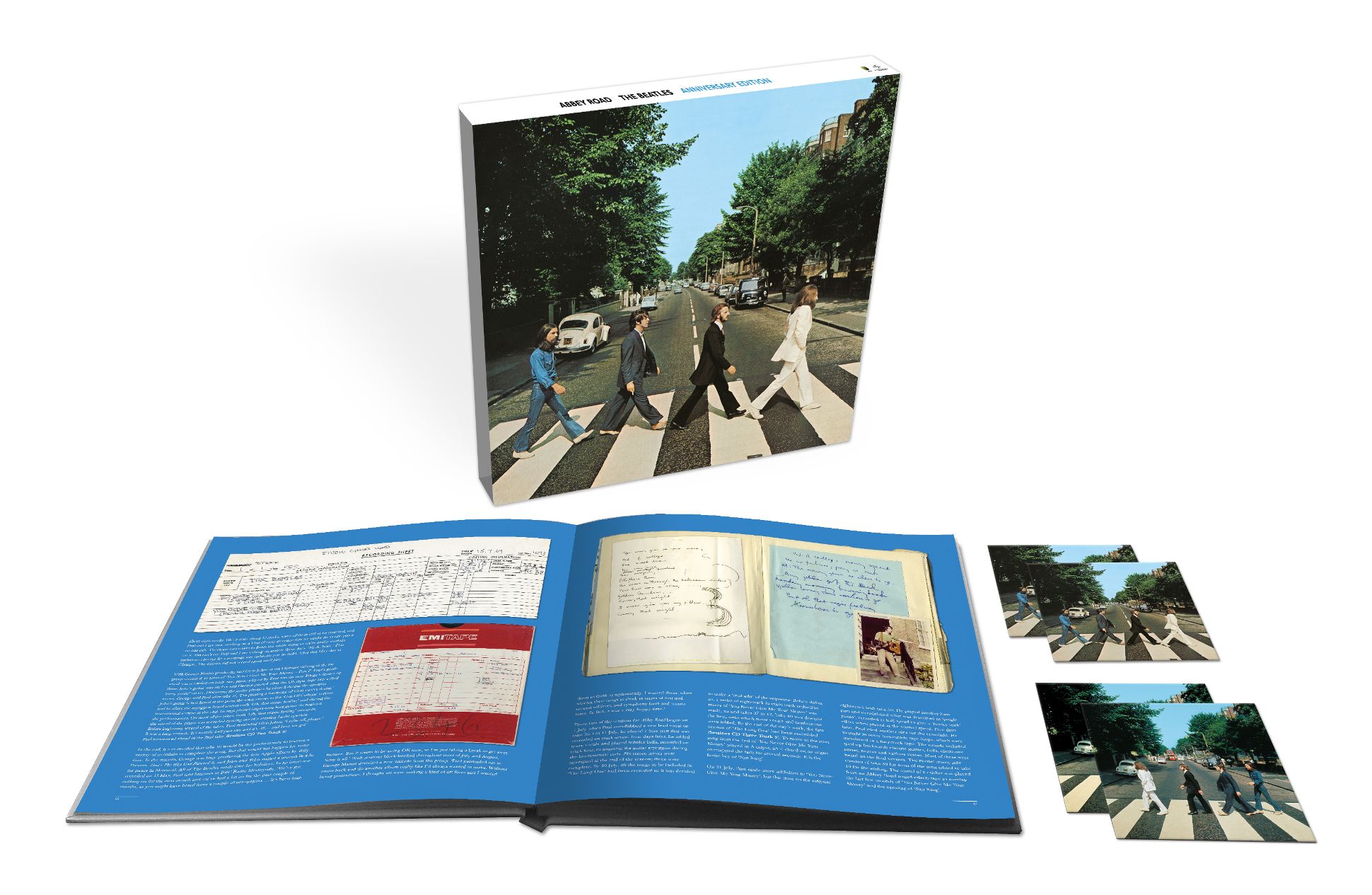

Sometime in 2019, George Martin's son Giles Martin, along with Sam Okell, returned to the master tapes of "You Never Give Me Your Money" to create a new stereo mix for inclusion in the multiple editions of the "Abbey Road" album to commemorate its 50th Anniversary. Subtle differences here include George Harrison's awkward guitar phrases in the song's conclusion not being faded down in the mix, and the bells and crickets in the final moments of the track sounding clearer, revealing that they are indeed tape loops. While they were at it, the engineering team also created stereo mixes of "take 36" of the original rhythm track from May 6th, 1969, and the trial edit of the entire medley as originally compiled on July 30th of that year. Sometime in 2019, George Martin's son Giles Martin, along with Sam Okell, returned to the master tapes of "You Never Give Me Your Money" to create a new stereo mix for inclusion in the multiple editions of the "Abbey Road" album to commemorate its 50th Anniversary. Subtle differences here include George Harrison's awkward guitar phrases in the song's conclusion not being faded down in the mix, and the bells and crickets in the final moments of the track sounding clearer, revealing that they are indeed tape loops. While they were at it, the engineering team also created stereo mixes of "take 36" of the original rhythm track from May 6th, 1969, and the trial edit of the entire medley as originally compiled on July 30th of that year.

A further recording of “You Never Give Me Your Money” as a medley with another “Abbey Road” song “Carry That Weight” (a couple of segments of the first song being heard in the second song on the original album, incidentally) was made during Paul's “Driving USA” tour of Spring 2002. It was an entirely solo performance by Paul on piano with no accompaniment from his band, the recording made on May 15th, 2002 at the Ice Palace in Tampa, Florida. This recording was included on both the American release “Back In The US” and the album “Back In The World” which was released in various other countries. A further recording of “You Never Give Me Your Money” as a medley with another “Abbey Road” song “Carry That Weight” (a couple of segments of the first song being heard in the second song on the original album, incidentally) was made during Paul's “Driving USA” tour of Spring 2002. It was an entirely solo performance by Paul on piano with no accompaniment from his band, the recording made on May 15th, 2002 at the Ice Palace in Tampa, Florida. This recording was included on both the American release “Back In The US” and the album “Back In The World” which was released in various other countries.

This live version consists of the first two sections of “You Never Give Me Your Money,” and then segues into the latter half of “Carry That Weight” that contains the same melody as the former song before reprising the first verse of “You Never Give My Your Money” to conclude this rendition nicely. Interestingly, Paul never took the time to learn the second lyric line from the second section of the song, instead singing, “And this is the bit where I don't know the words, but I don't think I'm even going to bother to try and learn them before the end of the tour.” This live version consists of the first two sections of “You Never Give Me Your Money,” and then segues into the latter half of “Carry That Weight” that contains the same melody as the former song before reprising the first verse of “You Never Give My Your Money” to conclude this rendition nicely. Interestingly, Paul never took the time to learn the second lyric line from the second section of the song, instead singing, “And this is the bit where I don't know the words, but I don't think I'm even going to bother to try and learn them before the end of the tour.”

Song Structure and Style

Because of the intended rambling nature of his composite song, going from one section to another in succession, “You Never Give Me Your Money” is similar only to John's “Happiness Is A Warm Gun,” which also meanders in the same way. Apart from the first section comprising a thrice-repeated eight-measure melody line, and some repeated melodic phrases in the second section, the song invariably just moves along in a haphazard fashion, like a conversation with a friend that keeps changing subjects. Because of the intended rambling nature of his composite song, going from one section to another in succession, “You Never Give Me Your Money” is similar only to John's “Happiness Is A Warm Gun,” which also meanders in the same way. Apart from the first section comprising a thrice-repeated eight-measure melody line, and some repeated melodic phrases in the second section, the song invariably just moves along in a haphazard fashion, like a conversation with a friend that keeps changing subjects.

The song begins with the first installment, considered the main thrust of the song given that the entire piece is named after the first words heard in this section. Paul plays a delicate eight-measure introduction on piano, George interjecting some melodic "bassy" guitar lines in measures four, seven and eight. The same eight measures are then repeated with Paul singing lead vocals which are single-tracked until the words “funny paper,” these vocals then being double-tracked for the remainder of this section of the song. George's guitar phrases are much more intricate in the eighth measure this time around, its last note being heard on top of Paul's lower bass note that comes in on the down-beat of the measure that follows it. The song begins with the first installment, considered the main thrust of the song given that the entire piece is named after the first words heard in this section. Paul plays a delicate eight-measure introduction on piano, George interjecting some melodic "bassy" guitar lines in measures four, seven and eight. The same eight measures are then repeated with Paul singing lead vocals which are single-tracked until the words “funny paper,” these vocals then being double-tracked for the remainder of this section of the song. George's guitar phrases are much more intricate in the eighth measure this time around, its last note being heard on top of Paul's lower bass note that comes in on the down-beat of the measure that follows it.

This section is then repeated again with different lyrics and some added elements. First off, John and George come in with delicate harmonies which are heard throughout these eight measures. Ringo is also heard lightly tapping cymbals while George's guitar and Paul's bass continue to be heard throughout. This eighth measure, however, deviates with Ringo adding a drum fill to go along with Paul's piano and bass work. This measure creates an appropriate segue into the "Out Of College" section of the song. This section is then repeated again with different lyrics and some added elements. First off, John and George come in with delicate harmonies which are heard throughout these eight measures. Ringo is also heard lightly tapping cymbals while George's guitar and Paul's bass continue to be heard throughout. This eighth measure, however, deviates with Ringo adding a drum fill to go along with Paul's piano and bass work. This measure creates an appropriate segue into the "Out Of College" section of the song.

This section can also be broken down into three smaller sections. The first, which is eight measures long, features two repeats of a four-measure passage and melody line beginning with the lyric “out of college, money spent.” The instrumentation consists of Paul playing two pianos (a simple pattern from the rhythm track and then a "jangle piano" overdub), Paul playing an impressive overdubbed walking bass part, John and George both playing rhythm guitar from the original rhythm track, and Ringo playing drums. Paul sings in his single-tracked Fats Domino style vocal throughout this section, not unlike the one deployed on “Lady Madonna.” Ringo plays an upbeat 4/4 swing beat with open hi-hat accents on the two- and four-beats, displaying a drum fill in both measures four and eight. This section can also be broken down into three smaller sections. The first, which is eight measures long, features two repeats of a four-measure passage and melody line beginning with the lyric “out of college, money spent.” The instrumentation consists of Paul playing two pianos (a simple pattern from the rhythm track and then a "jangle piano" overdub), Paul playing an impressive overdubbed walking bass part, John and George both playing rhythm guitar from the original rhythm track, and Ringo playing drums. Paul sings in his single-tracked Fats Domino style vocal throughout this section, not unlike the one deployed on “Lady Madonna.” Ringo plays an upbeat 4/4 swing beat with open hi-hat accents on the two- and four-beats, displaying a drum fill in both measures four and eight.

The second part of the "Out Of College" section, which starts with the lyric “but, oh that magic feeling,” is fourteen measures long. Ringo keeps the same time signature but shifts to a much more steady 4/4 rock feel for this section, tapping along nicely on the ride cymbal. This section actually consists of five repeats of a three-chord pattern, the final chord being cut off because of it transitioning into the first chord of the third part of the "Out Of College" section...You might want to write this down. Lol. The second part of the "Out Of College" section, which starts with the lyric “but, oh that magic feeling,” is fourteen measures long. Ringo keeps the same time signature but shifts to a much more steady 4/4 rock feel for this section, tapping along nicely on the ride cymbal. This section actually consists of five repeats of a three-chord pattern, the final chord being cut off because of it transitioning into the first chord of the third part of the "Out Of College" section...You might want to write this down. Lol.

The other elements of this section consist of the following: John repeats a simple electric guitar arpeggio that alters between the three chords in measures one through six, and then incorporates a more elaborate rendition of the same riffs in measures seven through fourteen. Paul plays simple piano on from the rhythm track, but also plays a simple overdubbed bass part in the background. George takes center stage with an impressive lead guitar part that winds throughout the final three repeats of the three chord pattern. John, Paul and George provide “aah” harmonies in measures seven through fourteen, Paul's awkward extended “whoooohhhhhh” after his final “nowhere to go” line in measure six being faded down in the mixing stage to be replaced by the aforementioned three-part harmonies. The other elements of this section consist of the following: John repeats a simple electric guitar arpeggio that alters between the three chords in measures one through six, and then incorporates a more elaborate rendition of the same riffs in measures seven through fourteen. Paul plays simple piano on from the rhythm track, but also plays a simple overdubbed bass part in the background. George takes center stage with an impressive lead guitar part that winds throughout the final three repeats of the three chord pattern. John, Paul and George provide “aah” harmonies in measures seven through fourteen, Paul's awkward extended “whoooohhhhhh” after his final “nowhere to go” line in measure six being faded down in the mixing stage to be replaced by the aforementioned three-part harmonies.

The third part of the "Out Of College" section is an elaborate seven-measure segue that takes us from the key of C, where the song currently is, back to the key of A where the song began. The primary focal point of the song is George's lead guitar work from the rhythm track which was double-tracked at a later session. John's rhythm guitar disappears during this section as does any trace of the original piano with the Leslie effect. Ringo's drums and Paul's bass propel the song through various elaborate chord changes and accents while the lead guitar keeps ascending to greater and greater heights until it lands firmly at his highest register on the downbeat of the third section of the song, referred to as "One Sweet Dream." The third part of the "Out Of College" section is an elaborate seven-measure segue that takes us from the key of C, where the song currently is, back to the key of A where the song began. The primary focal point of the song is George's lead guitar work from the rhythm track which was double-tracked at a later session. John's rhythm guitar disappears during this section as does any trace of the original piano with the Leslie effect. Ringo's drums and Paul's bass propel the song through various elaborate chord changes and accents while the lead guitar keeps ascending to greater and greater heights until it lands firmly at his highest register on the downbeat of the third section of the song, referred to as "One Sweet Dream."

This final section of the song is, including the extended fade, thirty six measures long. Ringo immediately reverts back to his 4/4 swing-style beat with open hi-hat accents on the two- and four-beats. John comes back in with rhythm chords on guitar while George fills in open gaps between lyrics with melodic phrases as he is known to do. Paul sings lead in measures one through fifteen while his bass overdub is heard throughout. A change in atmosphere momentarily occurs in measures five and six, John playing open chord strums during the lyrics “soon we'll be away from here / step on the gas and wipe that tear away,” Paul adding a quick bass flourish high up on the neck at the end of measure five. Also of interest is measure eight, between the lyric “one sweet dream / came true,” which is the only measure of the song that is in 2/4 time instead of 4/4. This final section of the song is, including the extended fade, thirty six measures long. Ringo immediately reverts back to his 4/4 swing-style beat with open hi-hat accents on the two- and four-beats. John comes back in with rhythm chords on guitar while George fills in open gaps between lyrics with melodic phrases as he is known to do. Paul sings lead in measures one through fifteen while his bass overdub is heard throughout. A change in atmosphere momentarily occurs in measures five and six, John playing open chord strums during the lyrics “soon we'll be away from here / step on the gas and wipe that tear away,” Paul adding a quick bass flourish high up on the neck at the end of measure five. Also of interest is measure eight, between the lyric “one sweet dream / came true,” which is the only measure of the song that is in 2/4 time instead of 4/4.