Search by Keyword

Sign Up Below for our MONTHLY BEATLES TRIVIA QUIZ!

|

“I WANT TO TELL YOU”

(George Harrison)

“All I needed to do was keep on writing and maybe eventually I would write something good,” George Harrison once stated. “It’s relativity. It did, however, provide me with an occupation.”

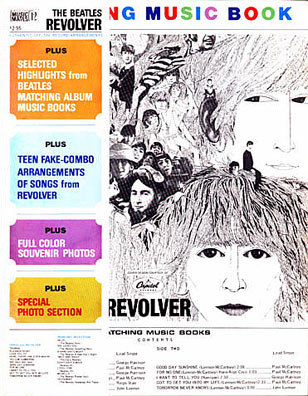

His occupation as a songwriter blossomed in 1966. Three George Harrison compositions on a single Beatles album was unheard of, that years’ “Revolver” being the only time this occurred (except for the double disc “White Album” which contained four). While many writers have taken notice that George’s total surrender to all things Eastern occured by that time in his career, his three songs on “Revolver” show the diversity of styles on his pallet. His occupation as a songwriter blossomed in 1966. Three George Harrison compositions on a single Beatles album was unheard of, that years’ “Revolver” being the only time this occurred (except for the double disc “White Album” which contained four). While many writers have taken notice that George’s total surrender to all things Eastern occured by that time in his career, his three songs on “Revolver” show the diversity of styles on his pallet.

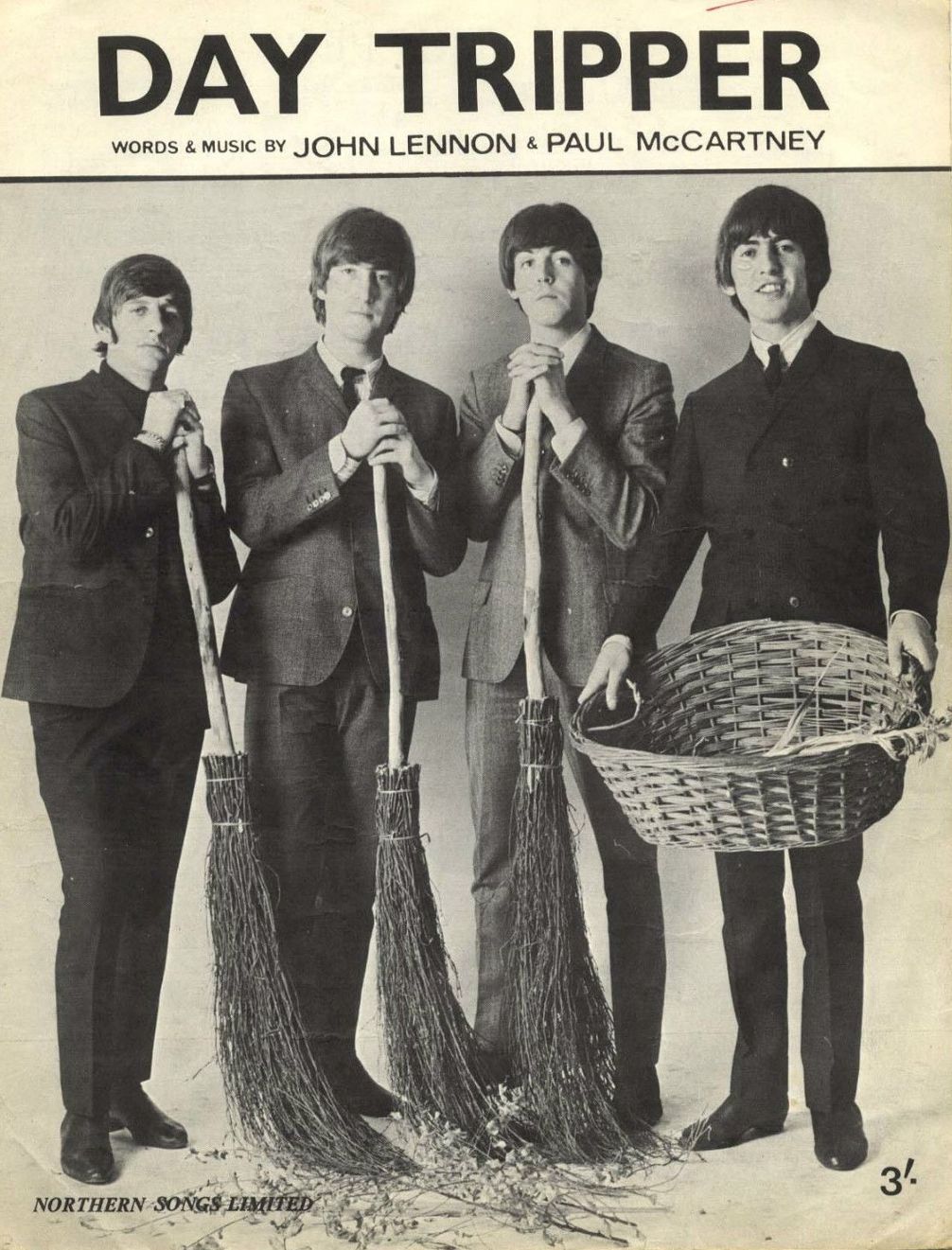

“Love You To” may have indeed delved into Indian instrumentation and structure full force, but his other two offerings for the album revealed different facets altogether. The hard-driving rock 'n' roll of “Taxman” contained both a blistering sound and message, while his third composition, the underrated “I Want To Tell You,” brings unique elements all its own. Back again is the classic two-measure guitar riff they were lately utilizing to great effect (witness “Day Tripper” and “Paperback Writer”) while the lyrics show George confessing his difficulties with intimacy while struggling to wrap his mind around some of his newly found Eastern philosophies. He may have had his insecurities as a composer at this point, hoping someday to “write something good,” but with a little attention from his bandmates and recording staff, it comes across quite nicely. “Love You To” may have indeed delved into Indian instrumentation and structure full force, but his other two offerings for the album revealed different facets altogether. The hard-driving rock 'n' roll of “Taxman” contained both a blistering sound and message, while his third composition, the underrated “I Want To Tell You,” brings unique elements all its own. Back again is the classic two-measure guitar riff they were lately utilizing to great effect (witness “Day Tripper” and “Paperback Writer”) while the lyrics show George confessing his difficulties with intimacy while struggling to wrap his mind around some of his newly found Eastern philosophies. He may have had his insecurities as a composer at this point, hoping someday to “write something good,” but with a little attention from his bandmates and recording staff, it comes across quite nicely.

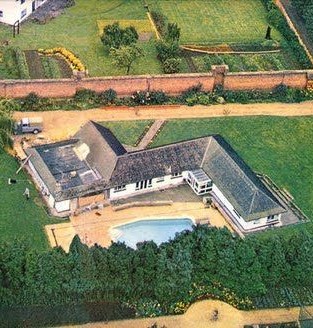

"Kinfauns" home of George and Pattie Harrison

Songwriting History

To help us understand the dynamic within The Beatles in 1966 that led to George obtaining three songs on the album "Revolver," Paul and John explained in an August interview that year how difficult it was to write new material. "When we've got an LP or a film coming up," Paul explained, "we've got to actually force ourselves to write. In fact, the last LP ("Revolver"): Wow! We took weeks just trying to get one written to get back into the swing of it." Lennon agreed, adding: "This last time was very impossible; Holiday spirit," quite possibly referring to quickly writing and recording the "Rubber Soul" album for its projected Christmas sales deadline. To help us understand the dynamic within The Beatles in 1966 that led to George obtaining three songs on the album "Revolver," Paul and John explained in an August interview that year how difficult it was to write new material. "When we've got an LP or a film coming up," Paul explained, "we've got to actually force ourselves to write. In fact, the last LP ("Revolver"): Wow! We took weeks just trying to get one written to get back into the swing of it." Lennon agreed, adding: "This last time was very impossible; Holiday spirit," quite possibly referring to quickly writing and recording the "Rubber Soul" album for its projected Christmas sales deadline.

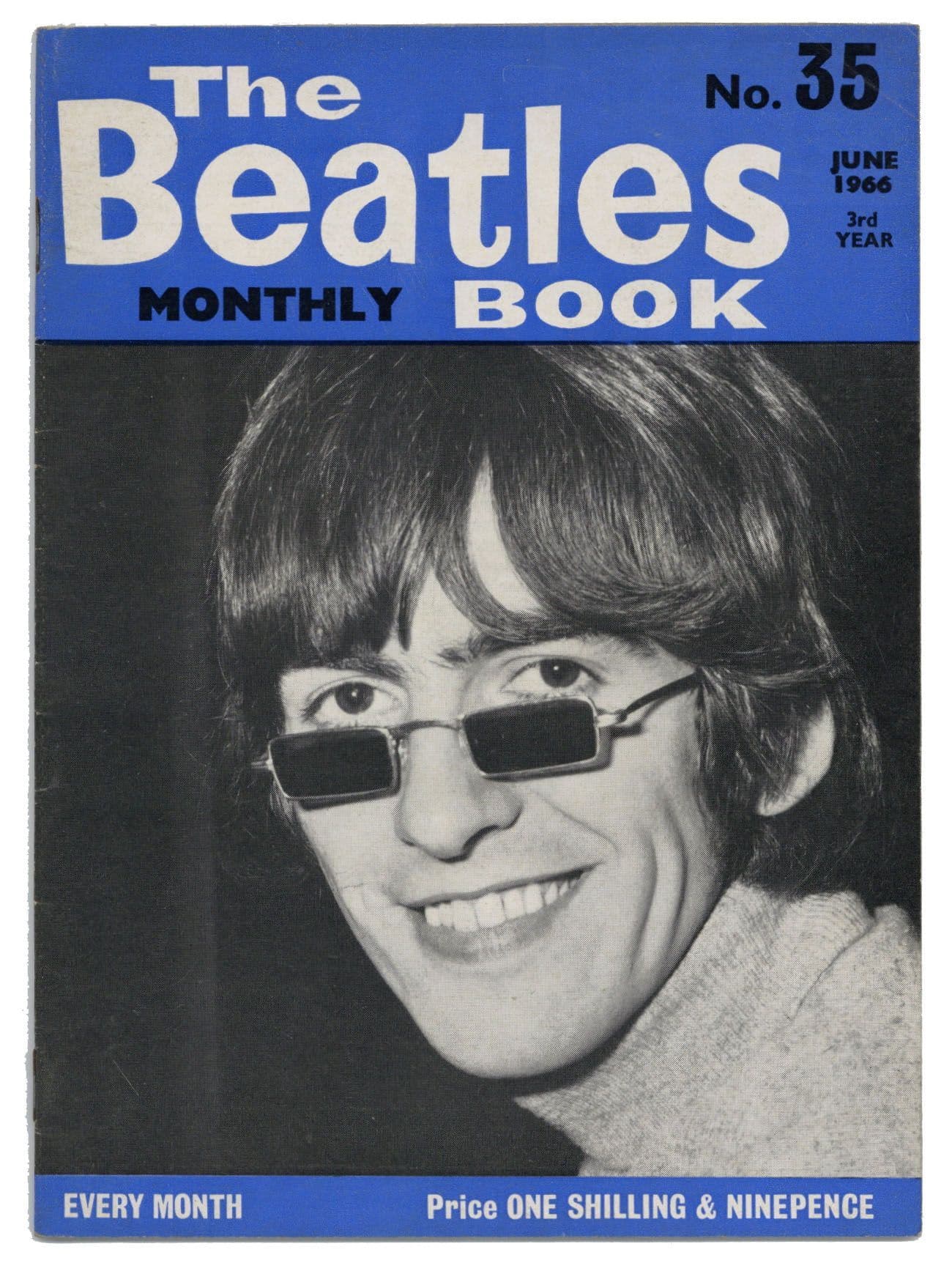

In one 1966 "Beatles Book Monthly" fan magazine, Harrison explained a small part that he played in easing some of the Lennon / McCartney songwriting pressure for that year. George states: "They gave me an awful lot of encouragement...Their reaction has been very good - if it hadn't, I think I would have crawled away. Now I know what it's all about, my songs have come more into perspective...my main trouble is the lyrics. I can't seem to write down what I want to say - it doesn't come over literally, so I compromise, usually far too much I suppose." In one 1966 "Beatles Book Monthly" fan magazine, Harrison explained a small part that he played in easing some of the Lennon / McCartney songwriting pressure for that year. George states: "They gave me an awful lot of encouragement...Their reaction has been very good - if it hadn't, I think I would have crawled away. Now I know what it's all about, my songs have come more into perspective...my main trouble is the lyrics. I can't seem to write down what I want to say - it doesn't come over literally, so I compromise, usually far too much I suppose."

Upon analysis, it appears that George is expressing in this song the awkwardness of dating, possibly having in mind his past struggles of getting intimate with his then wife Pattie Boyd, whom he married on January 21st, 1966. "My head is filled with things to say," he explains, but then "when you're here, all those words they seem to slip away." He may have rehearsed in his mind how he would perfectly express his feelings for her, but when the time came, his words just didn't come out like he thought they would. Upon analysis, it appears that George is expressing in this song the awkwardness of dating, possibly having in mind his past struggles of getting intimate with his then wife Pattie Boyd, whom he married on January 21st, 1966. "My head is filled with things to say," he explains, but then "when you're here, all those words they seem to slip away." He may have rehearsed in his mind how he would perfectly express his feelings for her, but when the time came, his words just didn't come out like he thought they would.

It appears that George had expectations of having sex with her on that given day but, when got "near" her, he realized that there are relationship "games" that need to be played that 'drag him down' to the realization that he's not goint to get laid that day. But "it's alright, I'll make you maybe next time around." 'Making' a girl is interpreted as having sex with her, as The Rolling Stones depicted in there song "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction" in the lyric "I'm tryin' to make some girl." George appears here to be resigning himself to the fact that sex is not going to happen on this occasion but will undoubtedly happen sometime soon. Interestingly, on the original lyric sheet (as seen below), he crossed out the line "I'll get through" and replaced it with "I'll make you." It appears that George had expectations of having sex with her on that given day but, when got "near" her, he realized that there are relationship "games" that need to be played that 'drag him down' to the realization that he's not goint to get laid that day. But "it's alright, I'll make you maybe next time around." 'Making' a girl is interpreted as having sex with her, as The Rolling Stones depicted in there song "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction" in the lyric "I'm tryin' to make some girl." George appears here to be resigning himself to the fact that sex is not going to happen on this occasion but will undoubtedly happen sometime soon. Interestingly, on the original lyric sheet (as seen below), he crossed out the line "I'll get through" and replaced it with "I'll make you."

Fearing that he's coming across "unkind" to Pattie, George explains, "It's only me, it's not my mind." In his 1980 book "I Me Mine," George states: “’I Want To Tell You’ is about the avalanche of thoughts that are so hard to write down or say or transmit,” adding that, incorporating newly acquired Eastern beliefs, he should have changed the lyrics to the first bridge to express the idea that "the mind is the thing that hops about telling us to do this or that - when what we need is to lose the mind." This new thought influenced George to change the lyric to "It isn't me, it's just my mind" when he performed the song during his 1991 Japan tour. This may either clarify his lyrical intentions or, as his original lyrics declare, "that is confusing things"! Fearing that he's coming across "unkind" to Pattie, George explains, "It's only me, it's not my mind." In his 1980 book "I Me Mine," George states: “’I Want To Tell You’ is about the avalanche of thoughts that are so hard to write down or say or transmit,” adding that, incorporating newly acquired Eastern beliefs, he should have changed the lyrics to the first bridge to express the idea that "the mind is the thing that hops about telling us to do this or that - when what we need is to lose the mind." This new thought influenced George to change the lyric to "It isn't me, it's just my mind" when he performed the song during his 1991 Japan tour. This may either clarify his lyrical intentions or, as his original lyrics declare, "that is confusing things"!

Returning to the original lyrics, Harrison relates that he feels "hung up" (originally "you hang me up" on the original lyric sheet) by not being able to express himself accurately, not understanding why this is happening. He replaces his original lyric "Maybe love will be the one thing to get me by" with the passive line "I don't mind / I could wait forever / I've got time," insinuating that his feelings for the girl are strong enough for waiting until it develops naturally. He then replaces his original fourth verse that begins with "If you should see me - and need my love to pass the time" with a new bridge that depicts how he wishes he knew her better "so I could speak my mind and tell you / maybe you'd understand." Returning to the original lyrics, Harrison relates that he feels "hung up" (originally "you hang me up" on the original lyric sheet) by not being able to express himself accurately, not understanding why this is happening. He replaces his original lyric "Maybe love will be the one thing to get me by" with the passive line "I don't mind / I could wait forever / I've got time," insinuating that his feelings for the girl are strong enough for waiting until it develops naturally. He then replaces his original fourth verse that begins with "If you should see me - and need my love to pass the time" with a new bridge that depicts how he wishes he knew her better "so I could speak my mind and tell you / maybe you'd understand."

As for his songwriting habits of 1966, he explained that year, “I’ve got a tape-recorder in the car, so I can sing on to that and work on it when I get home.” No precise date has ever been given, but one can assume that “I Want To Tell You” was written in this fashion sometime in the middle months of the year, being completed at "Kinfauns," his home in Surrey, England. As for his songwriting habits of 1966, he explained that year, “I’ve got a tape-recorder in the car, so I can sing on to that and work on it when I get home.” No precise date has ever been given, but one can assume that “I Want To Tell You” was written in this fashion sometime in the middle months of the year, being completed at "Kinfauns," his home in Surrey, England.

Recording History

With the sessions for the “Revolver” album winding down, The Beatles only needing four more songs to complete the album, George Harrison offered up his third composition for recording on June 2nd, 1966. This actually appears to have been the fourth offering from George for the album, author Mark Lewisohn indicating that “Isn’t It A Pity” was brought forward but rejected - this from a personal communication between Lewisohn and author Ian MacDonald as included in the third edition of “Revolution In The Head.” With the sessions for the “Revolver” album winding down, The Beatles only needing four more songs to complete the album, George Harrison offered up his third composition for recording on June 2nd, 1966. This actually appears to have been the fourth offering from George for the album, author Mark Lewisohn indicating that “Isn’t It A Pity” was brought forward but rejected - this from a personal communication between Lewisohn and author Ian MacDonald as included in the third edition of “Revolution In The Head.”

The group entered EMI Studio Two at 7 pm for an eight-hour session to work on George's new song. Much rehearsing was needed in order for all to learn the song and work out an arrangement. “This track proved very difficult for us to learn,” explained McCartney in the magazine Beat Instrumental. “I kept on getting it wrong, because it was written in a very odd way. It wasn’t 4/4 or waltz time or anything. Then I realized that it was regularly irregular, and, after that, we soon worked it out.” The group entered EMI Studio Two at 7 pm for an eight-hour session to work on George's new song. Much rehearsing was needed in order for all to learn the song and work out an arrangement. “This track proved very difficult for us to learn,” explained McCartney in the magazine Beat Instrumental. “I kept on getting it wrong, because it was written in a very odd way. It wasn’t 4/4 or waltz time or anything. Then I realized that it was regularly irregular, and, after that, we soon worked it out.”

Once an arrangement was worked out, the song's rhythm track began to be recorded, this consisting of George's electric guitar and Ringo's drums on track one of the four-track tape, while McCartney's piano and Lennon's tambourine were recorded on track two. One element of songwriting that George didn’t appear too keen on as of 1966 was coming up with titles. His first offering for the album, “Love You To,” did not have a title as the group was recording it, so engineer Geoff Emerick, in order to document the recording, named it after his favorite apple “Granny Smith.” This time around, the same problem occurred. Before "take one" was recorded, the following interchange was caught on tape: Once an arrangement was worked out, the song's rhythm track began to be recorded, this consisting of George's electric guitar and Ringo's drums on track one of the four-track tape, while McCartney's piano and Lennon's tambourine were recorded on track two. One element of songwriting that George didn’t appear too keen on as of 1966 was coming up with titles. His first offering for the album, “Love You To,” did not have a title as the group was recording it, so engineer Geoff Emerick, in order to document the recording, named it after his favorite apple “Granny Smith.” This time around, the same problem occurred. Before "take one" was recorded, the following interchange was caught on tape:

George Martin: “What are you going to call it, George?”

George Harrison: “I don’t know.”

John Lennon: “Granny Smith Part Friggin’ Two!”

Ringo Starr: "'Tell You.' That's a nice title. 'Tell you!'"

John Lennon: "You never had a title for any of your songs, except for 'Don't Bother Me.'"

Geoff Emerick was once again called upon to come up with yet another working title. He humorously decided to name the song “Laxton’s Superb” after another variety of apple. The session's tape box, however, shows that Geoff Emerick misspelled it as “Laxstone Superbe” (possibly on purpose), this later being crossed out and replaced with the proper title "I Want To Tell You." Geoff Emerick was once again called upon to come up with yet another working title. He humorously decided to name the song “Laxton’s Superb” after another variety of apple. The session's tape box, however, shows that Geoff Emerick misspelled it as “Laxstone Superbe” (possibly on purpose), this later being crossed out and replaced with the proper title "I Want To Tell You."

Five takes of the rhythm track were recorded on this tape, both "take one" and "take two" being false starts but then followed by a complete "take three" that they felt was good but thought they could possibly improve upon. After "take four," which fell apart after 39 seconds but was later included in the Deluxe editions of "Revolver" along with the introductory dialogue before "take one" as detailed above, "take five" made it through to the end of the song. However, a decision was apparently made to continue recording takes of the rhythm track onto what was left of the four-track tape used the previous day for sound effects for the song "Yellow Submarine," there apparently being a need to conserve expensive tape reels. Six additional attempts of the rhythm track for "I Want To Tell You," numbered takes 12 through 17, were found on the remainder of this tape, takes 6 through 11 probably being lost as the tape was undoubtedly rewound and recorded over so as not to waste tape (especially for a George Harrison song). Five takes of the rhythm track were recorded on this tape, both "take one" and "take two" being false starts but then followed by a complete "take three" that they felt was good but thought they could possibly improve upon. After "take four," which fell apart after 39 seconds but was later included in the Deluxe editions of "Revolver" along with the introductory dialogue before "take one" as detailed above, "take five" made it through to the end of the song. However, a decision was apparently made to continue recording takes of the rhythm track onto what was left of the four-track tape used the previous day for sound effects for the song "Yellow Submarine," there apparently being a need to conserve expensive tape reels. Six additional attempts of the rhythm track for "I Want To Tell You," numbered takes 12 through 17, were found on the remainder of this tape, takes 6 through 11 probably being lost as the tape was undoubtedly rewound and recorded over so as not to waste tape (especially for a George Harrison song).

As also included on Deluxe editions of the "Revolver" album, George Harrison asked George Martin after "take 15," "Do you wanna wind back a bit?" (as they probably had already done on that day), the producer responding "We're all right," which undoubtedly meant that there was still a lot of blank tape left on the reel. Apparently someone came to the studio door during "take 15," which prompted George Martin to ask Paul, "Who was at the door?" "The commissionaire," Paul responded, possibly meaning Sir Joseph Lockwood, who was currently the chairman of EMI. "The commissionaire, coming in with the red light on?" a shocked George Martin replied, indicating that he should have known better than to attempt to enter a recording studio while a session is in progress. "Yeah, sneaky, sneak, sneak, tell-tale tidit!" Paul responded. As also included on Deluxe editions of the "Revolver" album, George Harrison asked George Martin after "take 15," "Do you wanna wind back a bit?" (as they probably had already done on that day), the producer responding "We're all right," which undoubtedly meant that there was still a lot of blank tape left on the reel. Apparently someone came to the studio door during "take 15," which prompted George Martin to ask Paul, "Who was at the door?" "The commissionaire," Paul responded, possibly meaning Sir Joseph Lockwood, who was currently the chairman of EMI. "The commissionaire, coming in with the red light on?" a shocked George Martin replied, indicating that he should have known better than to attempt to enter a recording studio while a session is in progress. "Yeah, sneaky, sneak, sneak, tell-tale tidit!" Paul responded.

In a rather unprecedented move for the time, the intention with these rhythm tracks was to record the bass later as an overdub, this becoming a commonplace occurance throughout the next year and beyond. This would allow for a more sonic presence to the bass guitar on the finished product, not to mention, as suggested by Ian MacDonald in his book “Revolution In The Head,” allowing Paul “to control the harmonic structure of the music.” In a rather unprecedented move for the time, the intention with these rhythm tracks was to record the bass later as an overdub, this becoming a commonplace occurance throughout the next year and beyond. This would allow for a more sonic presence to the bass guitar on the finished product, not to mention, as suggested by Ian MacDonald in his book “Revolution In The Head,” allowing Paul “to control the harmonic structure of the music.”

After all 17 takes were complete, it was decided that "take three" from the first four-track tape was the best after all. Therefore, after this tape was returned to, overdubs began. George sang his lead vocals simultaneously with harmonies from John and Paul on track three, all of these vocals then being double-tracked onto track four. Then, according to the book "The Beatles Recording Sessions," Ringo overdubbed maracas and Paul overdubbed another piano performance onto these tracks as well. After all 17 takes were complete, it was decided that "take three" from the first four-track tape was the best after all. Therefore, after this tape was returned to, overdubs began. George sang his lead vocals simultaneously with harmonies from John and Paul on track three, all of these vocals then being double-tracked onto track four. Then, according to the book "The Beatles Recording Sessions," Ringo overdubbed maracas and Paul overdubbed another piano performance onto these tracks as well.

Because all four tracks of the tape were filled, a tape-to-tape reduction copy was made to free up more tracks for future overdubs on another day, all rhythm track instruments being allocated to track one and all vocals, maracas and additional piano put on track two of the new tape. This reduction mix turned "take three" into "take four," not to be confused with the actual "take four" of the rhythm track that was previously deemed unsuitable, this being a false start that appears on Deluxe editions of "Revolver." This completed the day’s activities for the group, the bulk of the song being complete by about 3 am the next morning. Because all four tracks of the tape were filled, a tape-to-tape reduction copy was made to free up more tracks for future overdubs on another day, all rhythm track instruments being allocated to track one and all vocals, maracas and additional piano put on track two of the new tape. This reduction mix turned "take three" into "take four," not to be confused with the actual "take four" of the rhythm track that was previously deemed unsuitable, this being a false start that appears on Deluxe editions of "Revolver." This completed the day’s activities for the group, the bulk of the song being complete by about 3 am the next morning.

Geoff Emerick speculates: “One really got the impression that George was being given a certain amount of time to do his tracks whereas the others could spend as long as they wanted. One felt under more pressure when doing one of George’s songs.” While eight hours sounds like a good amount of time, by 1966 Beatles standards, this was a quickie. George Martin reusing a previous four-track tape for later takes of the song can also be viewed as an indication that Harrison's compositions weren't considered that important. Geoff Emerick speculates: “One really got the impression that George was being given a certain amount of time to do his tracks whereas the others could spend as long as they wanted. One felt under more pressure when doing one of George’s songs.” While eight hours sounds like a good amount of time, by 1966 Beatles standards, this was a quickie. George Martin reusing a previous four-track tape for later takes of the song can also be viewed as an indication that Harrison's compositions weren't considered that important.

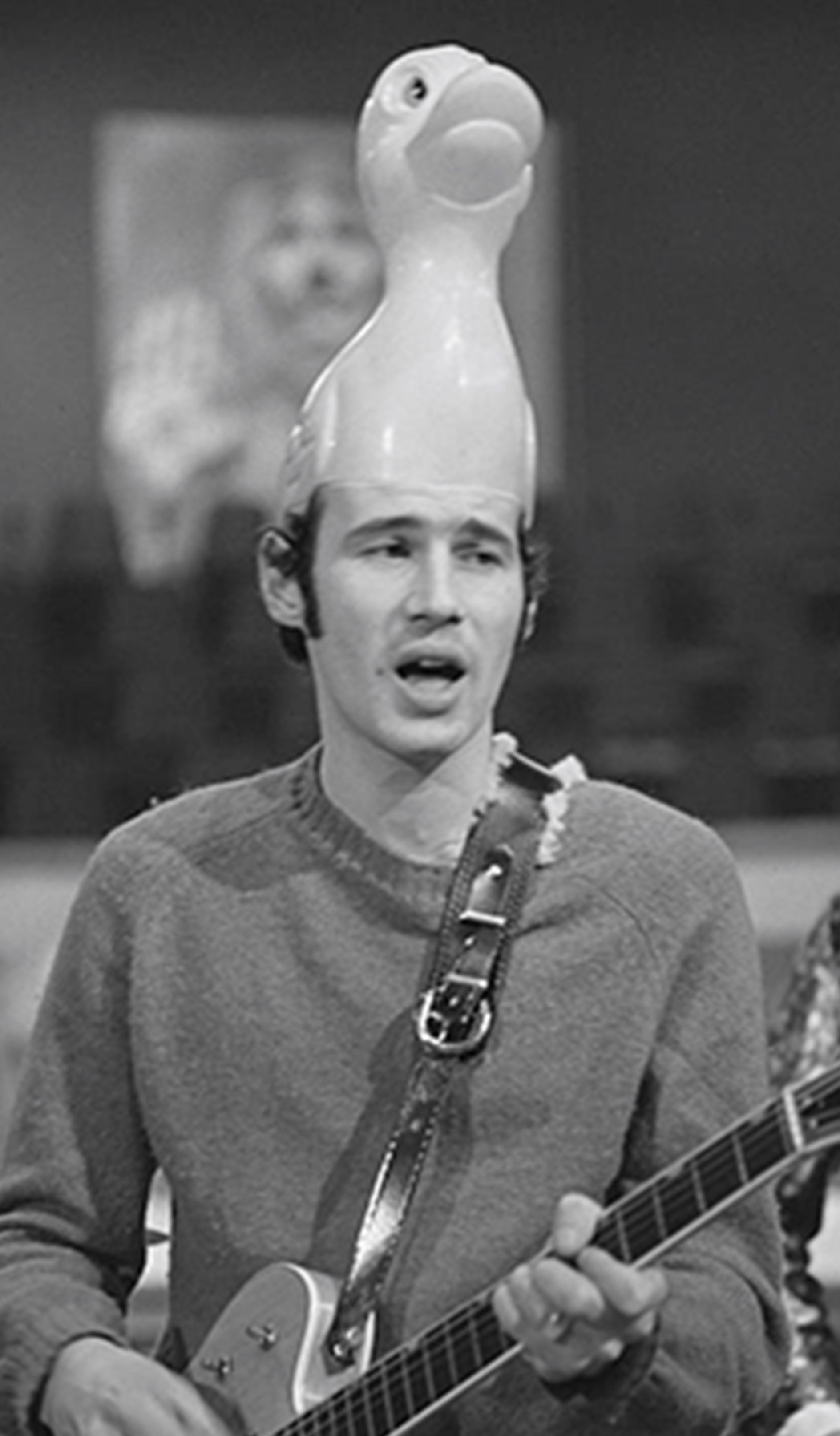

Neil Innes, British singer/songwriter who’s claim to fame is creating parodies of The Beatles music in the project “The Rutles,” happened to have been in EMI Studios on this day for his recording experience as part of the comedic group “The Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band.” He reportedly was taking a break from recording his group's second single "Alley Oop" in EMI Studio Three and was in one of the hallways when he heard The Beatles playing back the tape of “I Want To Tell You” at full volume. "I thought I would sneak out and see what they were up to," Innes stated in the Deluxe editions of "Revolver," "Listening through the door, I could hear quite well what they were doing...The F and the E (of Paul's piano performance) was just so exciting, and the guitar riff! I'd never heard anything quite like it." Years later, when Innes visited George at his home, he relates, "Just outside the kitchen there was a little upright piano and a guitar. We talked about the F over the E and George picked up the guitar and we just played it together. It was a great moment." In 1967, a year after Innes eavesdropped on this Beatles session, he and his band would appear in the stripper scene of The Beatles’ film “Magical Mystery Tour.” Neil Innes, British singer/songwriter who’s claim to fame is creating parodies of The Beatles music in the project “The Rutles,” happened to have been in EMI Studios on this day for his recording experience as part of the comedic group “The Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band.” He reportedly was taking a break from recording his group's second single "Alley Oop" in EMI Studio Three and was in one of the hallways when he heard The Beatles playing back the tape of “I Want To Tell You” at full volume. "I thought I would sneak out and see what they were up to," Innes stated in the Deluxe editions of "Revolver," "Listening through the door, I could hear quite well what they were doing...The F and the E (of Paul's piano performance) was just so exciting, and the guitar riff! I'd never heard anything quite like it." Years later, when Innes visited George at his home, he relates, "Just outside the kitchen there was a little upright piano and a guitar. We talked about the F over the E and George picked up the guitar and we just played it together. It was a great moment." In 1967, a year after Innes eavesdropped on this Beatles session, he and his band would appear in the stripper scene of The Beatles’ film “Magical Mystery Tour.”

The next day, June 3rd, 1966, the group once again convened in EMI Studio Two at 7 pm to finish off “Laxton’s Superb” which, at some point during this session, was changed to the title “I Don’t Know” as unintentionally suggested by George the day before. With two tracks of the new tape available, Paul overdubbed his bass guitar on track three while hand-claps were recorded towards the end of the song on track four. With this complete, four mono mixes of the song were made in the EMI Studio Two control room by producer George Martin, Geoff Emerick and 2nd engineer Phil McDonald. The first of these mono mixes was the one placed on the mono pressings of the released album. After some mixing work on the previously recorded “Yellow Submarine” was tackled, The Beatles and EMI staff called it a night at about 2:30 am the following morning. Two copies of this first mono mix were made on June 6th, 1966 in the control room of EMI Studio Three by the same EMI staff, these mixes being numbered “remixes 5 and 6.” The name of the song was finally now indicated as “I Want To Tell You,” the obvious title indicated in the song's lyrics. The next day, June 3rd, 1966, the group once again convened in EMI Studio Two at 7 pm to finish off “Laxton’s Superb” which, at some point during this session, was changed to the title “I Don’t Know” as unintentionally suggested by George the day before. With two tracks of the new tape available, Paul overdubbed his bass guitar on track three while hand-claps were recorded towards the end of the song on track four. With this complete, four mono mixes of the song were made in the EMI Studio Two control room by producer George Martin, Geoff Emerick and 2nd engineer Phil McDonald. The first of these mono mixes was the one placed on the mono pressings of the released album. After some mixing work on the previously recorded “Yellow Submarine” was tackled, The Beatles and EMI staff called it a night at about 2:30 am the following morning. Two copies of this first mono mix were made on June 6th, 1966 in the control room of EMI Studio Three by the same EMI staff, these mixes being numbered “remixes 5 and 6.” The name of the song was finally now indicated as “I Want To Tell You,” the obvious title indicated in the song's lyrics.

Two stereo mixes of the song were made on June 21st, 1966 in the EMI Studio Three control room by the same EMI staff, but the identity of which of these mixes made it on the album is not known. All instrumentation and vocals are panned slightly left of center on the released stereo mix while the overdubbed bass track is panned mostly to the right. Two stereo mixes of the song were made on June 21st, 1966 in the EMI Studio Three control room by the same EMI staff, but the identity of which of these mixes made it on the album is not known. All instrumentation and vocals are panned slightly left of center on the released stereo mix while the overdubbed bass track is panned mostly to the right.

Sometime between December 1st and 17th, 1991, Harrison and friends recorded a live version of "I Want To Tell You" during their brief but successful tour of Japan, the results appearing on the subsequent album “Live In Japan.” This extended version of the song features multiple guitar solos from George’s good friend Eric Clapton. Sometime between December 1st and 17th, 1991, Harrison and friends recorded a live version of "I Want To Tell You" during their brief but successful tour of Japan, the results appearing on the subsequent album “Live In Japan.” This extended version of the song features multiple guitar solos from George’s good friend Eric Clapton.

Sometime in 2022, George Martin's son Giles Martin, along with engineer Sam Okell, returned to the original "I Want To Tell You" recordings to create a vibrant new stereo mix using AI technology to further separate the instrumentation for a more palatable stereo experience. This new mix was included on various reissues of "Revolver" released later in the year. While they were at it, this team also created a stereo mix of the incomplete "take four" as recorded on June 2nd, 1966, the above detailed preliminary speech from "take one" and concluding dialogue from "take 15" also recorded on that day being tacked on for good measure. Sometime in 2022, George Martin's son Giles Martin, along with engineer Sam Okell, returned to the original "I Want To Tell You" recordings to create a vibrant new stereo mix using AI technology to further separate the instrumentation for a more palatable stereo experience. This new mix was included on various reissues of "Revolver" released later in the year. While they were at it, this team also created a stereo mix of the incomplete "take four" as recorded on June 2nd, 1966, the above detailed preliminary speech from "take one" and concluding dialogue from "take 15" also recorded on that day being tacked on for good measure.

Song Structure and Style

The familiar Beatles pattern of verses and bridges, comprising ‘verse/ verse/ bridge/ verse/ bridge/ verse’ (or aababa), is used here by George, with an intro and conclusion thrown in to round out the proceedings. Even though the song was composed by the group's lead guitarist, no solo performance is deemed necessary here. Its uniqueness, as we’ll see, lies within the arrangement. The familiar Beatles pattern of verses and bridges, comprising ‘verse/ verse/ bridge/ verse/ bridge/ verse’ (or aababa), is used here by George, with an intro and conclusion thrown in to round out the proceedings. Even though the song was composed by the group's lead guitarist, no solo performance is deemed necessary here. Its uniqueness, as we’ll see, lies within the arrangement.

The tricky fade-in technique of 1964’s “Eight Days A Week” is repeated here with George’s infectious guitar riff appearing as if from the far-off distance. The riff is repeated twice by Harrison alone, although a good portion of the first riff is hidden in near silence. The second half of this eight-measure introduction brings in the rest of the band. The third repeat of the guitar riff brings Paul stabbing piano chords to accent the chord changes with Ringo pounding his snare drum on the two- and four-beat of each measure. The fourth repeat of the riff brings in John on tambourine, first hitting the one-beat of the seventh measure but then violently shaking the instrument from the two-beat through the remainder of this and the next measure, joined by Paul on overdubbed bass guitar in the final two beats of the eighth measure. The tricky fade-in technique of 1964’s “Eight Days A Week” is repeated here with George’s infectious guitar riff appearing as if from the far-off distance. The riff is repeated twice by Harrison alone, although a good portion of the first riff is hidden in near silence. The second half of this eight-measure introduction brings in the rest of the band. The third repeat of the guitar riff brings Paul stabbing piano chords to accent the chord changes with Ringo pounding his snare drum on the two- and four-beat of each measure. The fourth repeat of the riff brings in John on tambourine, first hitting the one-beat of the seventh measure but then violently shaking the instrument from the two-beat through the remainder of this and the next measure, joined by Paul on overdubbed bass guitar in the final two beats of the eighth measure.

George’s guitar riff is also worthy of examination. Unlike “Day Tripper” before it, it is played reservedly on the lower strings of his guitar. Its up-and-down melody line uses the low A note as the bottom "jump off point" which is returned to repeatedly during the riff, this being easily performed using the open A string. The riff’s disorienting quality is due to unique characteristics, which include the downbeat which precedes the actual one-beat of the first measure, and also the staggered triplets of the second half. As George plays it solo in the first four measures of the song, the listener may not have his footing yet – it’s only when Ringo’s steady snare beat comes in that we get the intended rhythm of the song. George’s guitar riff is also worthy of examination. Unlike “Day Tripper” before it, it is played reservedly on the lower strings of his guitar. Its up-and-down melody line uses the low A note as the bottom "jump off point" which is returned to repeatedly during the riff, this being easily performed using the open A string. The riff’s disorienting quality is due to unique characteristics, which include the downbeat which precedes the actual one-beat of the first measure, and also the staggered triplets of the second half. As George plays it solo in the first four measures of the song, the listener may not have his footing yet – it’s only when Ringo’s steady snare beat comes in that we get the intended rhythm of the song.

Then there are the disorienting verses. Each verse has an uneven eleven-measure length, this being divided among four meandering vocal phrases. Another twist is that the first chord change occurs in the middle of the fourth measure, not at the beginning of a measure as usually happens. Musicians may suspect a change in meter somewhere in these verses, but if you parse it out, it always remains at 4/4. Cover artists seem to get tripped up here, such as Ted Nugent’s version where he felt he needed to change the fourth measure to 2/4 time to make it more uniform. Then there are the disorienting verses. Each verse has an uneven eleven-measure length, this being divided among four meandering vocal phrases. Another twist is that the first chord change occurs in the middle of the fourth measure, not at the beginning of a measure as usually happens. Musicians may suspect a change in meter somewhere in these verses, but if you parse it out, it always remains at 4/4. Cover artists seem to get tripped up here, such as Ted Nugent’s version where he felt he needed to change the fourth measure to 2/4 time to make it more uniform.

The first verse brings in Harrison’s lead vocals, with his bending vocal work on the words “teeeellll you,” which appears to be influenced by the dilruba, an Indian musical instrument the sound of which seems to have inspired even the vocal work of The Beatles. Evidence of this can be seen in how George perfectly mimics the playing of the dilruba on “Within You Without You,” not to mention the exaggerated bending melody lines sung by all vocalists on “Rain.” Another aspect of George’s melody line in “I Want To Tell You” is his use of syncopated notes, something he was especially fond of at this time as evidenced in its habitual appearance in his compositions (note “If I Needed Someone” as a prime example). The first verse brings in Harrison’s lead vocals, with his bending vocal work on the words “teeeellll you,” which appears to be influenced by the dilruba, an Indian musical instrument the sound of which seems to have inspired even the vocal work of The Beatles. Evidence of this can be seen in how George perfectly mimics the playing of the dilruba on “Within You Without You,” not to mention the exaggerated bending melody lines sung by all vocalists on “Rain.” Another aspect of George’s melody line in “I Want To Tell You” is his use of syncopated notes, something he was especially fond of at this time as evidenced in its habitual appearance in his compositions (note “If I Needed Someone” as a prime example).

The Beatles fall into a swing groove at this point, Ringo playing a strident pattern with light hi-hat taps, Paul accenting the quarter-notes on both the piano and bass guitar, and light percussion from Ringo on maracas and John on tambourine. John and Paul join in on harmonies on the second vocal line “my head is filled with things to say.” Arguably the most disturbing element of the song, however, appears in the sixth through ninth measures, this being the alarming flat-ninth notes played by Paul on the piano. All becomes well again in the final two measures of the verse as the charming guitar riff is repeated with John and Paul’s harmonies layered above it on the words “slip away.” The instrumentation also seems to "slip away" at this point, the tambourine violently shaking once again to usher in the second verse that follows. The Beatles fall into a swing groove at this point, Ringo playing a strident pattern with light hi-hat taps, Paul accenting the quarter-notes on both the piano and bass guitar, and light percussion from Ringo on maracas and John on tambourine. John and Paul join in on harmonies on the second vocal line “my head is filled with things to say.” Arguably the most disturbing element of the song, however, appears in the sixth through ninth measures, this being the alarming flat-ninth notes played by Paul on the piano. All becomes well again in the final two measures of the verse as the charming guitar riff is repeated with John and Paul’s harmonies layered above it on the words “slip away.” The instrumentation also seems to "slip away" at this point, the tambourine violently shaking once again to usher in the second verse that follows.

After a brief tumble of toms from Ringo, the second verse has the identical structure and instrumentation as the first. This segues nicely into the first eight-measure bridge, which is sung solo by George. The swing beat disolves for a signature "Beatles break" in the seventh measure on the line “confusing things” with only Paul hitting a rising note on the piano that indicates a slight chord change. The eighth measure ends the slight lull in the proceedings with Ringo's thunderous drum fill and Paul playing a rapid-fire A-note repetition to usher in the third verse which follows. After a brief tumble of toms from Ringo, the second verse has the identical structure and instrumentation as the first. This segues nicely into the first eight-measure bridge, which is sung solo by George. The swing beat disolves for a signature "Beatles break" in the seventh measure on the line “confusing things” with only Paul hitting a rising note on the piano that indicates a slight chord change. The eighth measure ends the slight lull in the proceedings with Ringo's thunderous drum fill and Paul playing a rapid-fire A-note repetition to usher in the third verse which follows.

The third verse and second bridge that follows it are also identical in structure and instrumentation, but the reoccurance of the third verse afterwards adds in the boys' hand-clapping overdub. The final measure of this verse concludes with the guitar riff as usual; however, Harrison keeps repeating the riff as it fades off into the sunset. The third time it is repeated, all three vocalists come back in with the final words of the verse, namely “I’ve got time.” This is then repeated and held out during the fade with Paul’s harmony jumping around in a rather Eastern flavor while John gives a few final taps on the tambourine and Paul noodles on the piano. The third verse and second bridge that follows it are also identical in structure and instrumentation, but the reoccurance of the third verse afterwards adds in the boys' hand-clapping overdub. The final measure of this verse concludes with the guitar riff as usual; however, Harrison keeps repeating the riff as it fades off into the sunset. The third time it is repeated, all three vocalists come back in with the final words of the verse, namely “I’ve got time.” This is then repeated and held out during the fade with Paul’s harmony jumping around in a rather Eastern flavor while John gives a few final taps on the tambourine and Paul noodles on the piano.

George’s guitar work, mostly noticed with his recurring guitar riffs and hardly apparent elsewhere in the song if at all, was performed proficiently and flawlessly every time. Fellow Traveling Wilbury Jeff Lynne relates concerning this guitar riff, "George was really good at the unexpected. He would outthink and think his way round and come to something completely different from how any ordinary songwriter would do it. To me, that's a magical riff." George's vocals depict the mental confusion of the lyrics quite well, the double-tracking emphasizing the bending notes in the verses with a blurring exaggeration. George’s guitar work, mostly noticed with his recurring guitar riffs and hardly apparent elsewhere in the song if at all, was performed proficiently and flawlessly every time. Fellow Traveling Wilbury Jeff Lynne relates concerning this guitar riff, "George was really good at the unexpected. He would outthink and think his way round and come to something completely different from how any ordinary songwriter would do it. To me, that's a magical riff." George's vocals depict the mental confusion of the lyrics quite well, the double-tracking emphasizing the bending notes in the verses with a blurring exaggeration.

Paul plays a big role in the instrumentation and, therefore, in the overall presentation of the song. Two full tracks of piano make the instrument the dominant feature of the recording, his overdubbed bass also adding a deep tone to the track. His pedal-point style bass work is less engaging than we’re used to hearing from him at this point in The Beatles' career, although he does stray away from it momentarily during the third measure of each bridge. And, as we always expect, his harmony vocals are well delivered. Paul plays a big role in the instrumentation and, therefore, in the overall presentation of the song. Two full tracks of piano make the instrument the dominant feature of the recording, his overdubbed bass also adding a deep tone to the track. His pedal-point style bass work is less engaging than we’re used to hearing from him at this point in The Beatles' career, although he does stray away from it momentarily during the third measure of each bridge. And, as we always expect, his harmony vocals are well delivered.

John Lennon only picks up the tambourine as his musical instrument on this track, although it is performed with much bravado. His harmony work is also well sung. Ringo shows himself up to the task at hand, his steady and forceful drum playing exhibits strength and confidence right down to the blistering drum fills. His maraca playing may be subdued but, then again, maybe we can detect some vigorous shaking on this instrument as well as John’s tambourine at the end of each verse. John Lennon only picks up the tambourine as his musical instrument on this track, although it is performed with much bravado. His harmony work is also well sung. Ringo shows himself up to the task at hand, his steady and forceful drum playing exhibits strength and confidence right down to the blistering drum fills. His maraca playing may be subdued but, then again, maybe we can detect some vigorous shaking on this instrument as well as John’s tambourine at the end of each verse.

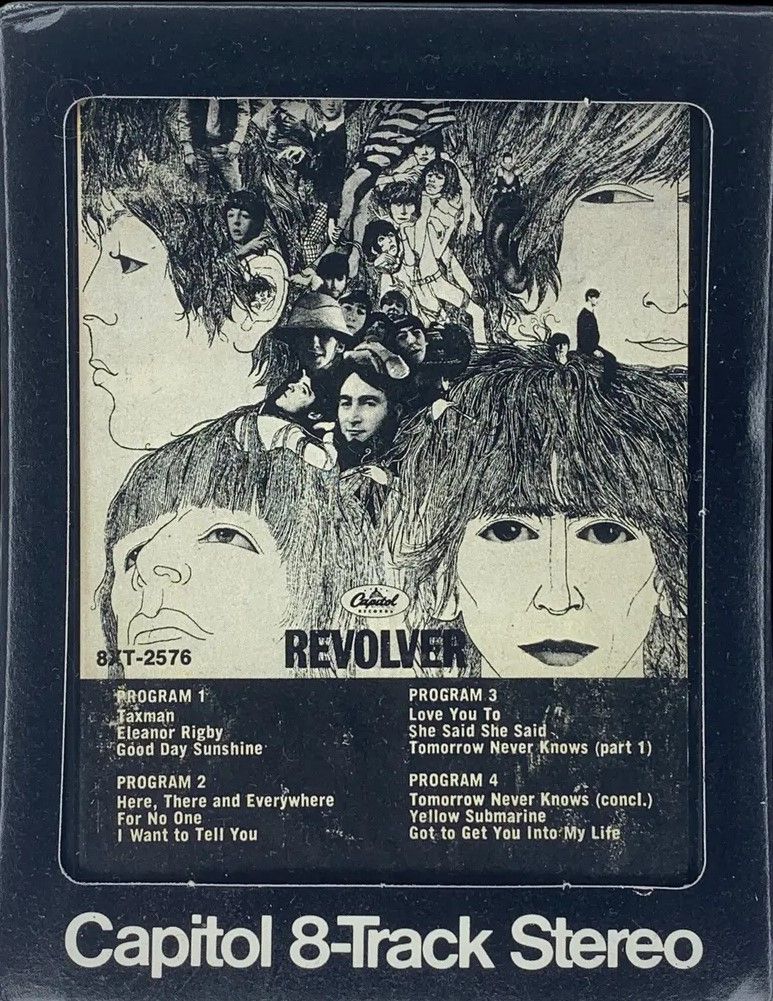

American Releases

Capitol Record’s eleven-track “Revolver” album debuted in America on August 8th, 1966. A slightly more dominant placement of “I Want To Tell You,” that of mid-side two, accentuates the powerhouse groove of the song, especially following the low-keyed mellow feel of “For No One.” The American version of the "Revolver" album got a compact disc release on January 21st, 2014, with both the mono and stereo versions contained on a single CD. Capitol Record’s eleven-track “Revolver” album debuted in America on August 8th, 1966. A slightly more dominant placement of “I Want To Tell You,” that of mid-side two, accentuates the powerhouse groove of the song, especially following the low-keyed mellow feel of “For No One.” The American version of the "Revolver" album got a compact disc release on January 21st, 2014, with both the mono and stereo versions contained on a single CD.

Sometime in 1967, Capitol released Beatles music on a brand new but short-lived format called "Playtapes." These tape cartridges did not have the capability to include entire albums, so two four-song versions of "Revolver" were released in this portable format, "I Want To Tell You" being on one of them. These "Playtapes" are highly collectable today. Sometime in 1967, Capitol released Beatles music on a brand new but short-lived format called "Playtapes." These tape cartridges did not have the capability to include entire albums, so two four-song versions of "Revolver" were released in this portable format, "I Want To Tell You" being on one of them. These "Playtapes" are highly collectable today.

The first time the full original British "Revolver” album was made available in America was on the "Original Master Recording" vinyl edition released through Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab sometime in 1985. This album included "I Want To Tell You" and was prepared utilizing half-speed mastering technology from the original master tape on loan from EMI. This version of the album was only available for a short time and is quite collectible today. The first time the full original British "Revolver” album was made available in America was on the "Original Master Recording" vinyl edition released through Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab sometime in 1985. This album included "I Want To Tell You" and was prepared utilizing half-speed mastering technology from the original master tape on loan from EMI. This version of the album was only available for a short time and is quite collectible today.

The full fourteen-track British “Revolver” album was released in the US on CD on April 30th, 1987, a vinyl edition coming out on July 21st, 1987. As it is heard here, George’s song was slightly overshadowed by John’s “Dr. Robert” which precedes it. This album was then re-released in a remastered condition on CD on September 9th, 2009 and on vinyl on November 13th, 2012. A remarkable newly mixed edition of "Revolver" created by Giles Martin was released on vinyl and CD on October 28th, 2022. The full fourteen-track British “Revolver” album was released in the US on CD on April 30th, 1987, a vinyl edition coming out on July 21st, 1987. As it is heard here, George’s song was slightly overshadowed by John’s “Dr. Robert” which precedes it. This album was then re-released in a remastered condition on CD on September 9th, 2009 and on vinyl on November 13th, 2012. A remarkable newly mixed edition of "Revolver" created by Giles Martin was released on vinyl and CD on October 28th, 2022.

Also on September 9th, 2009, the CD box set “The Beatles In Mono” was released, which comprised the entire mono Beatles catalog, the original mono “I Want To Tell You” first appearing in the US at this time. The vinyl edition of this box set was first released on September 9th, 2014. Also on September 9th, 2009, the CD box set “The Beatles In Mono” was released, which comprised the entire mono Beatles catalog, the original mono “I Want To Tell You” first appearing in the US at this time. The vinyl edition of this box set was first released on September 9th, 2014.

In promotion of the 2014 box set "The US Albums," a 25-song sampler compact disc was distributed on January 21st, 2014, this containing the stereo mix of "I Want To Tell You."

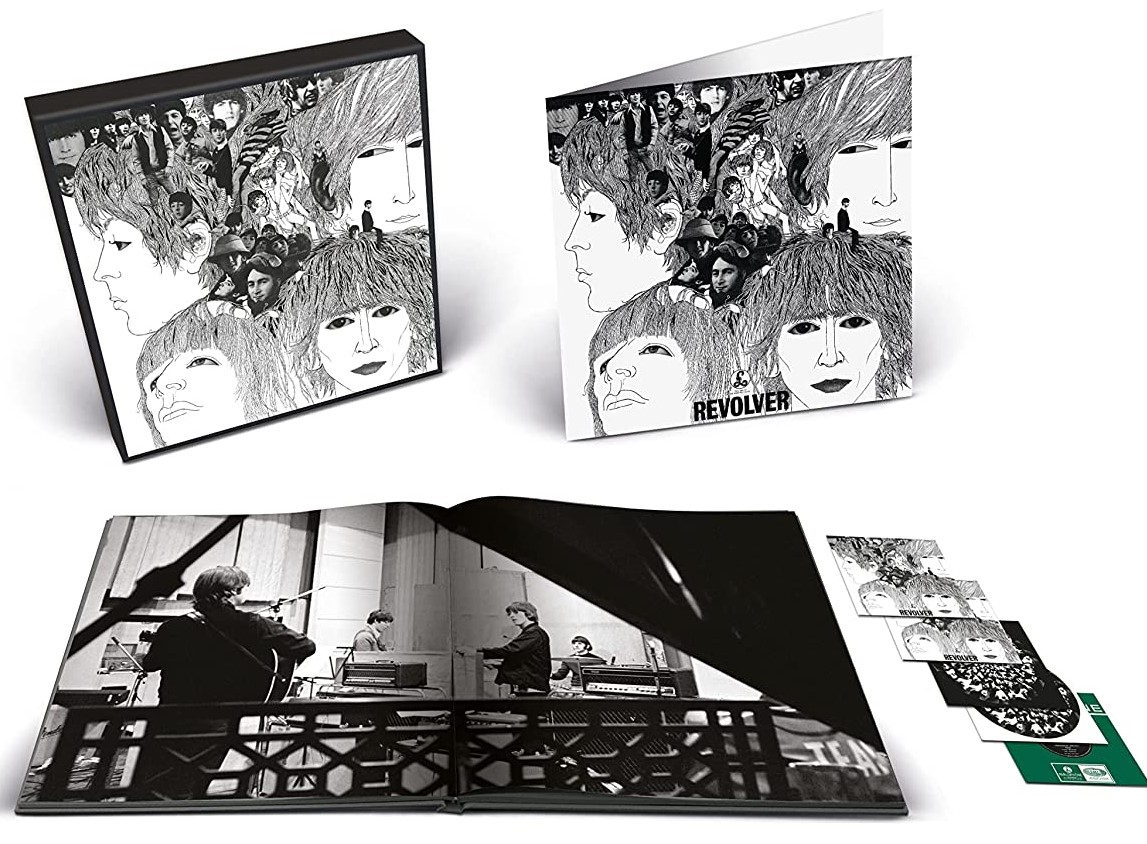

On October 28th, 2022, various new editions of the “Revolver” album were released that feature the amazing new stereo mix created by Giles Martin. The “Special Edition Deluxe 2CD Set” features “I Want To Tell You” in its new stereo mix as well as the incomplete “take four” with speech from "take one" and "take 15" from the original 1966 sessions. The “Deluxe Edition,” which is available as a 5 CD box set and a 4LP / 1 EP box set, includes these versions as well as the original mono master from 1966. The 2022 Giles Martin stereo mix of the album was also made available for the first time as a vinyl picture disc for a limited time. On October 28th, 2022, various new editions of the “Revolver” album were released that feature the amazing new stereo mix created by Giles Martin. The “Special Edition Deluxe 2CD Set” features “I Want To Tell You” in its new stereo mix as well as the incomplete “take four” with speech from "take one" and "take 15" from the original 1966 sessions. The “Deluxe Edition,” which is available as a 5 CD box set and a 4LP / 1 EP box set, includes these versions as well as the original mono master from 1966. The 2022 Giles Martin stereo mix of the album was also made available for the first time as a vinyl picture disc for a limited time.

On July 13th, 1992, George’s double-disc “Live In Japan” came out featuring his band’s extended version of “I Want To Tell You” as the lead off track.

Live Performances

Although it could have made a powerful presence as a George lead vocal song for The Beatles final 1966 US Tour, this was not to be. The song did get performed live by George, however, during his December 1st thru 17th, 1991 Japanese tour, and then again during his benefit concert for the Natural Law Party at the Royal Albert Hall in London on April 6th, 1992. Although it could have made a powerful presence as a George lead vocal song for The Beatles final 1966 US Tour, this was not to be. The song did get performed live by George, however, during his December 1st thru 17th, 1991 Japanese tour, and then again during his benefit concert for the Natural Law Party at the Royal Albert Hall in London on April 6th, 1992.

Conclusion

“I think the trouble with George was that he was never treated on the same level as having the same quality of songwriting, by anyone – by John, by Paul or by me,” admits George Martin. “I’m as guilty in that respect. I was the guy who used to say: ‘If he’s got a song, we’ll let him have it on the album’ - very condescendingly. I know he must have felt really bad about that…George was a loner and I’m afraid that was made the worse by the three of us. I’m sorry about that now.” “I think the trouble with George was that he was never treated on the same level as having the same quality of songwriting, by anyone – by John, by Paul or by me,” admits George Martin. “I’m as guilty in that respect. I was the guy who used to say: ‘If he’s got a song, we’ll let him have it on the album’ - very condescendingly. I know he must have felt really bad about that…George was a loner and I’m afraid that was made the worse by the three of us. I’m sorry about that now.”

I’m sure I’m not alone in particularly thinking of George’s song “I Want To Tell You” when I review this apology from George Martin. This composition had all the elements of a powerhouse pop hit, right down to the innovative recurring guitar riff. With a little more finesse, such as some heavy electric rhythm guitar work (such as on some of Lennon’s songs on the album), this could easily have been a standout track on “Revolver.” Cover versions made over the years reveal this to be true, such as the 1979 version by rocker Ted Nugent. George’s patience is very noteworthy here, as if the guitarist somehow knew his time in the production spotlight would soon come. As he serendipitously states in this song: “I could wait forever – I’ve got time.” I’m sure I’m not alone in particularly thinking of George’s song “I Want To Tell You” when I review this apology from George Martin. This composition had all the elements of a powerhouse pop hit, right down to the innovative recurring guitar riff. With a little more finesse, such as some heavy electric rhythm guitar work (such as on some of Lennon’s songs on the album), this could easily have been a standout track on “Revolver.” Cover versions made over the years reveal this to be true, such as the 1979 version by rocker Ted Nugent. George’s patience is very noteworthy here, as if the guitarist somehow knew his time in the production spotlight would soon come. As he serendipitously states in this song: “I could wait forever – I’ve got time.”

“I Want To Tell You”

Written by: George Harrison

-

Song Written: May, 1966

-

Song Recorded: June 2 & 3, 1966

-

First US Release Date: August 8, 1966

-

First US Album Release: Capitol #ST-2576 “Revolver”

-

US Single Release: n/a

-

Highest Chart Position: n/a

-

British Album Release: Parlophone #PCS 7009 “Revolver”

-

Length: 2:30

-

Key: A major

-

Producer: George Martin

-

Engineers: Geoff Emerick, Phil McDonald

Instrumentation (most likely):

-

George Harrison - Lead Vocals, Lead Guitar (1961 Sonic Blue Fender Stratocaster), handclaps

-

Paul McCartney -- Piano (Hamburg Steinway Baby Grand), Bass Guitar (1964 Rickenbacker 4001S), Harmony Vocals, handclaps

-

John Lennon - Tambourine, Harmony Vocals, handclaps

-

Ringo Starr – Drums (1964 Ludwig Super Classic Black Oyster Pearl), maracas, handclaps

Written and compiled by Dave Rybaczewski

|

IF YOU WOULD LIKE TO MAKE A DONATION TO KEEP THIS WEBSITE UP AND RUNNING, PLEASE CLICK BELOW!

Sign Up Below for our MONTHLY BEATLES TRIVIA QUIZ!

|