Search by Keyword

|

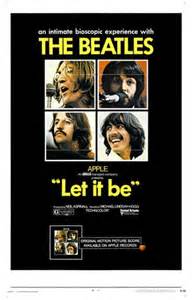

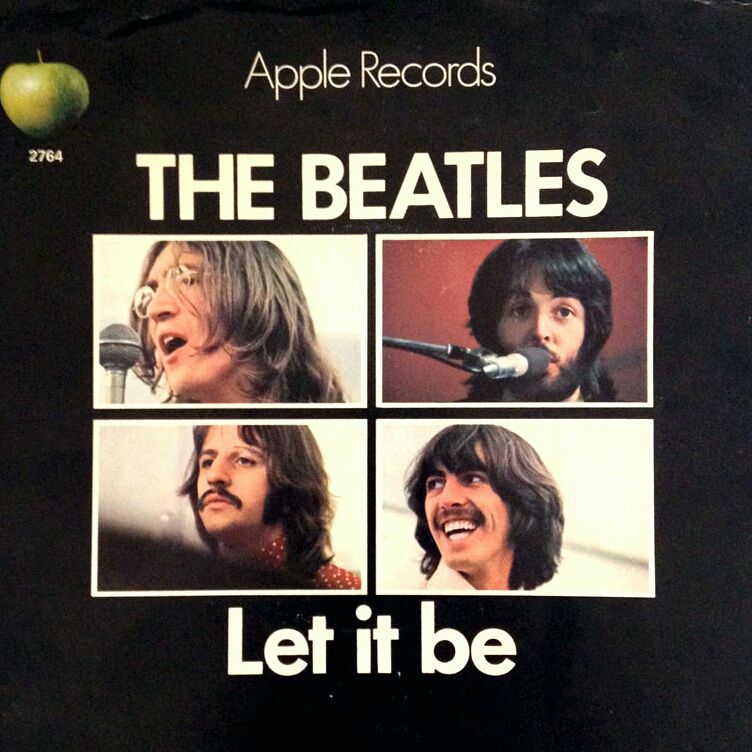

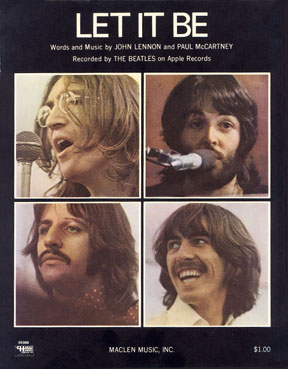

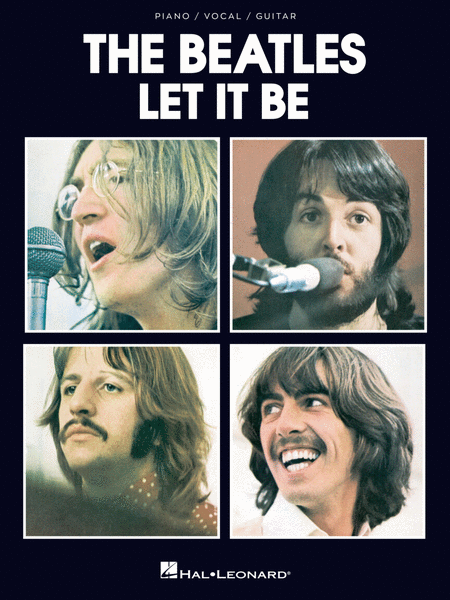

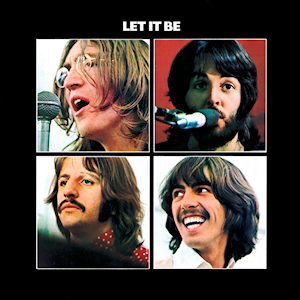

“LET IT BE”

(John Lennon – Paul McCartney)

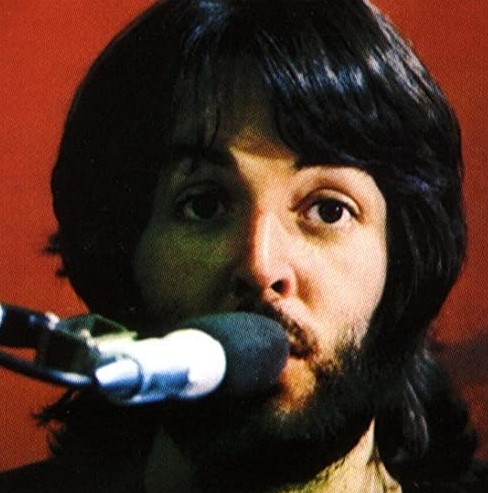

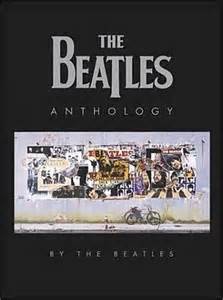

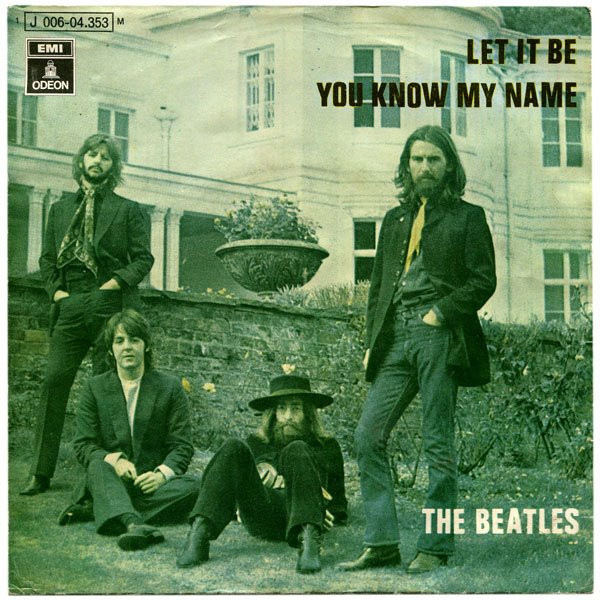

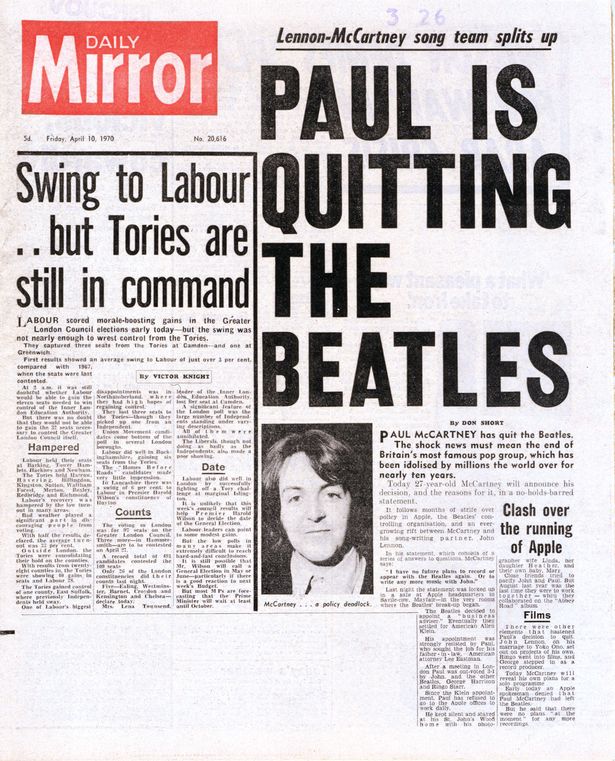

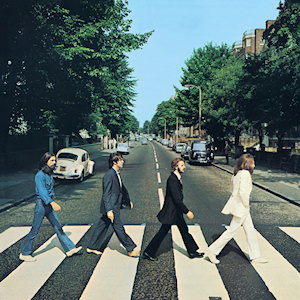

Fans may not have known it at the time, but in early September of 1968, Paul recognized that The Beatles were having some major difficulties and sensed that the end was imminent. The Beatles had been recording the “White Album” for over three months with tensions mounting and arguments abounding. With John's drug use at an all-time high, and with him having Yoko by his side at virtually every session, it became apparent that the band no longer shared a united vision for the future. As detailed in the “Beatles Anthology” book, George even went on record as saying that he “was losing interest in being 'fab'...I was growing out of that kind of thing.” Fans may not have known it at the time, but in early September of 1968, Paul recognized that The Beatles were having some major difficulties and sensed that the end was imminent. The Beatles had been recording the “White Album” for over three months with tensions mounting and arguments abounding. With John's drug use at an all-time high, and with him having Yoko by his side at virtually every session, it became apparent that the band no longer shared a united vision for the future. As detailed in the “Beatles Anthology” book, George even went on record as saying that he “was losing interest in being 'fab'...I was growing out of that kind of thing.”

Paul, however, believed in The Beatles. He found himself on what he thought was a steady course with his band-mates, only to look around and realize that he was on that road alone. He felt that, with concerted effort, he could use his gifts of persuasion to rally the troups back together and bring them to their senses, aiming them in the unified direction they had been following for the past decade. And this did appear to work for a time, but with three unenthusiastic participants contributing somewhat reluctantly. Paul, however, believed in The Beatles. He found himself on what he thought was a steady course with his band-mates, only to look around and realize that he was on that road alone. He felt that, with concerted effort, he could use his gifts of persuasion to rally the troups back together and bring them to their senses, aiming them in the unified direction they had been following for the past decade. And this did appear to work for a time, but with three unenthusiastic participants contributing somewhat reluctantly.

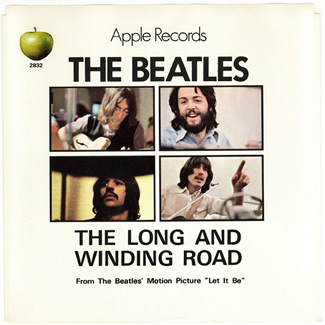

Despite McCartney's struggle to keep things going, as all Beatles fans desired, he eventually had no choice but to admit defeat. After all, if your associates wish not to continue as associates, there's not much you can do about it. With this realization in mind, and having been propelled as he was by a dream to help him come to that conclusion, Paul wrote one of the most beloved and iconic Beatles songs of their career. It may not have been released until after the inevitible disolving of the band but, in retrospect, the timing couldn't have been better. With the breaking-up of the greatest and most popular music group in the world being officially anounced in early 1970, the world was consoled in song. We were all told to, simply, just “Let It Be.” Despite McCartney's struggle to keep things going, as all Beatles fans desired, he eventually had no choice but to admit defeat. After all, if your associates wish not to continue as associates, there's not much you can do about it. With this realization in mind, and having been propelled as he was by a dream to help him come to that conclusion, Paul wrote one of the most beloved and iconic Beatles songs of their career. It may not have been released until after the inevitible disolving of the band but, in retrospect, the timing couldn't have been better. With the breaking-up of the greatest and most popular music group in the world being officially anounced in early 1970, the world was consoled in song. We were all told to, simply, just “Let It Be.”

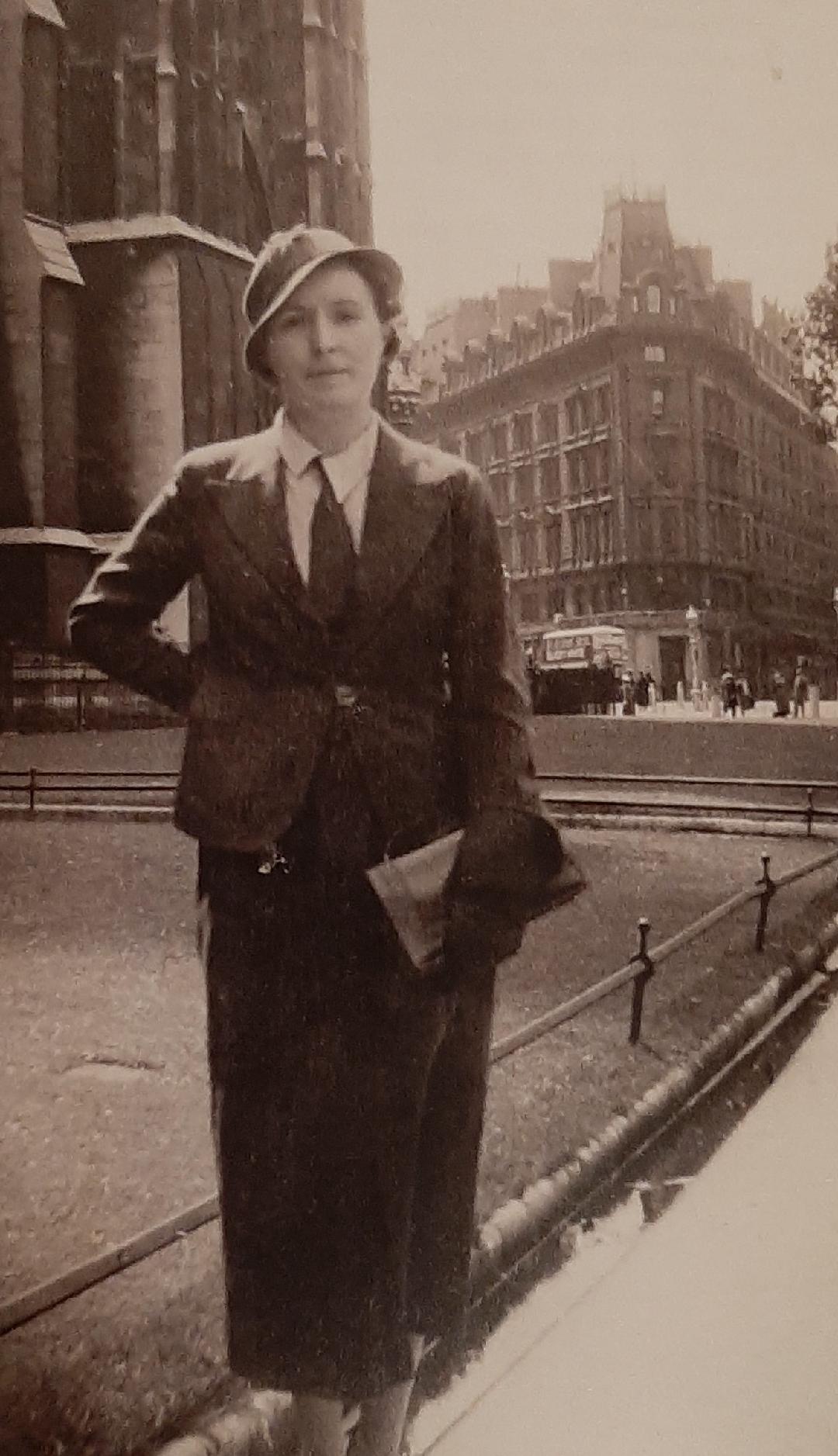

Songwriting History

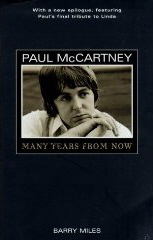

On October 31st, 1956, Paul's mother Mary Patricia McCartney had passed away from breast cancer. “I would have liked to have seen the boys growing up” was one of the last things she had said on that day. “She was great,” Paul relates in his book “Many Years From Now.” “She was a really wonderful woman and really did pull the family along, which is probably why in the end she dies of a stress-related illness. She was, as so many woman are, the unsung leader of the family.” On October 31st, 1956, Paul's mother Mary Patricia McCartney had passed away from breast cancer. “I would have liked to have seen the boys growing up” was one of the last things she had said on that day. “She was great,” Paul relates in his book “Many Years From Now.” “She was a really wonderful woman and really did pull the family along, which is probably why in the end she dies of a stress-related illness. She was, as so many woman are, the unsung leader of the family.”

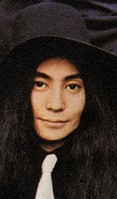

“This was a very difficult period,” Paul continues, referring to the emotional climate of early September 1968. "John was with Yoko full time, and our relationship was beginning to crumble: John and I were going through a very tense period. The breakup of The Beatles was looming and I was very nervy. Personally it was a very difficult time for me. I think the drugs, the stress, tiredness and everything had really started to take its toll. I somehow managed to miss a lot of the bad effects of all that, but looking back on this period, I think I was having troubles." In his 2021 book "The Lyrics," Paul adds: "Yoko was literally in the middle of the recording session, and that was challenging. But it was also something we had to deal with. Unless there was a really serious problem - unless one of us said, 'I can't sing with her there' - we just had to let it be. We weren't very confrontational, so we just bottled it up and got on with it. We were northern lads, and that was part of our culture. Grin and bear it." “This was a very difficult period,” Paul continues, referring to the emotional climate of early September 1968. "John was with Yoko full time, and our relationship was beginning to crumble: John and I were going through a very tense period. The breakup of The Beatles was looming and I was very nervy. Personally it was a very difficult time for me. I think the drugs, the stress, tiredness and everything had really started to take its toll. I somehow managed to miss a lot of the bad effects of all that, but looking back on this period, I think I was having troubles." In his 2021 book "The Lyrics," Paul adds: "Yoko was literally in the middle of the recording session, and that was challenging. But it was also something we had to deal with. Unless there was a really serious problem - unless one of us said, 'I can't sing with her there' - we just had to let it be. We weren't very confrontational, so we just bottled it up and got on with it. We were northern lads, and that was part of our culture. Grin and bear it."

Paul continues: "One night during this tense time, I had a dream. I saw my mum, who'd been dead ten years or so. And it was so great to see her because that's a wonderful thing about dreams: you actually are reunited with that person for a second; there they are and you appear to both be physically together again. It was so wonderful for me and she was very reassuring. In the dream she said, 'It'll be all right.' I'm not sure if she used the words 'Let it be' but that was the gist of her advice. It was, 'Don't worry too much, it will turn out okay.' It was such a sweet dream. I woke up thinking, 'Oh, it was really great to visit with her again.' I felt very blessed to have that dream. So that got me writing the song 'Let It Be.' I literally started off 'Mother Mary,' which was her name. 'When I find myself in times of trouble,' which I certainly found myself in. The song was based on that dream." Paul continues: "One night during this tense time, I had a dream. I saw my mum, who'd been dead ten years or so. And it was so great to see her because that's a wonderful thing about dreams: you actually are reunited with that person for a second; there they are and you appear to both be physically together again. It was so wonderful for me and she was very reassuring. In the dream she said, 'It'll be all right.' I'm not sure if she used the words 'Let it be' but that was the gist of her advice. It was, 'Don't worry too much, it will turn out okay.' It was such a sweet dream. I woke up thinking, 'Oh, it was really great to visit with her again.' I felt very blessed to have that dream. So that got me writing the song 'Let It Be.' I literally started off 'Mother Mary,' which was her name. 'When I find myself in times of trouble,' which I certainly found myself in. The song was based on that dream."

In "The Lyrics," Paul adds: "Seeing my mum's beautiful, kind face and being with her in a peachful place was very comforting. I immediately felt at ease, and loved and protected. My mum was very reassuring and, like so many women often are, she was also the one who kept our family going. She kept our spirits up. She seemed to realize I was worried about what was going on in my life and what would happen, and she said to me, 'Everything will be all right. Let it be.'" In "The Lyrics," Paul adds: "Seeing my mum's beautiful, kind face and being with her in a peachful place was very comforting. I immediately felt at ease, and loved and protected. My mum was very reassuring and, like so many women often are, she was also the one who kept our family going. She kept our spirits up. She seemed to realize I was worried about what was going on in my life and what would happen, and she said to me, 'Everything will be all right. Let it be.'"

Paul's concerns about The Beatles' future were caught on tape during the filming of the “Let It Be” movie: “I think we've been very negative since (Beatles manager) Mr. Epstein passed way. We haven't been positive. That's why all of us in turn have been sick of the group. There's nothing positive in it. It's a bit of a drag. The only way for it not to be a bit of a drag is for the four of us to think – should we make it positive or should we forget it?” Concerning the writing of the song “Let It Be,” which occurred at McCartney's 7 Cavendish Avenue home in St. John's Wood, London, Paul continues in Steve Turner's book “A Hard Day's Write” as follows: "I wrote it when all those business problems started to get me down. I really was passing through my 'hour of darkness' and writing the song was my way of exorcizing the ghosts." In "The Lyrics," Paul writes: "I'd been pushing the band to go back out and play some club dates - to get back to basics and just bond again as a band, end the decade like we'd begun it, just playing for the love of it." Paul's concerns about The Beatles' future were caught on tape during the filming of the “Let It Be” movie: “I think we've been very negative since (Beatles manager) Mr. Epstein passed way. We haven't been positive. That's why all of us in turn have been sick of the group. There's nothing positive in it. It's a bit of a drag. The only way for it not to be a bit of a drag is for the four of us to think – should we make it positive or should we forget it?” Concerning the writing of the song “Let It Be,” which occurred at McCartney's 7 Cavendish Avenue home in St. John's Wood, London, Paul continues in Steve Turner's book “A Hard Day's Write” as follows: "I wrote it when all those business problems started to get me down. I really was passing through my 'hour of darkness' and writing the song was my way of exorcizing the ghosts." In "The Lyrics," Paul writes: "I'd been pushing the band to go back out and play some club dates - to get back to basics and just bond again as a band, end the decade like we'd begun it, just playing for the love of it."

Interestingly, roadie and companion Mal Evans recalled a conversation he had with Paul that presents a convincing alternative story about the origin of “Let It Be.” In an interview with Laura Gross on November 29th, 1975 (a week before his death), Mal Evans related a conversation he had with Paul concerning a rough sketch of a song he began to write during The Beatles' stay in India in the early months of 1968. In Keith Badman's book “The Beatles Off The Record,” Mal recounts: "Paul was meditating one day, they were writing all the time, and I came to him in a vision. I was just standing there, saying, 'Let it be, let it be,' and that's where the song came from. It was funny; I had driven him back from a session one night a few months later. It was three o-clock in the morning, it was raining, it was dark in London and we were sitting in the car, just before he went in, just laughing and talking. He said, 'Mal, I've got a new song and it's called “Let It Be,” and I sing about 'Mother Malcolm,' but he was a bit shy. So, he turned to me and said, 'Would you mind if I said, “Mother Mary,” because people might not understand?' So, I said, 'Sure.' But, he was lovely." It was at this time that he may have concocted the story of the vision of his mother's dream to tell the world about the inspiration to the song "Let It Be." Interestingly, roadie and companion Mal Evans recalled a conversation he had with Paul that presents a convincing alternative story about the origin of “Let It Be.” In an interview with Laura Gross on November 29th, 1975 (a week before his death), Mal Evans related a conversation he had with Paul concerning a rough sketch of a song he began to write during The Beatles' stay in India in the early months of 1968. In Keith Badman's book “The Beatles Off The Record,” Mal recounts: "Paul was meditating one day, they were writing all the time, and I came to him in a vision. I was just standing there, saying, 'Let it be, let it be,' and that's where the song came from. It was funny; I had driven him back from a session one night a few months later. It was three o-clock in the morning, it was raining, it was dark in London and we were sitting in the car, just before he went in, just laughing and talking. He said, 'Mal, I've got a new song and it's called “Let It Be,” and I sing about 'Mother Malcolm,' but he was a bit shy. So, he turned to me and said, 'Would you mind if I said, “Mother Mary,” because people might not understand?' So, I said, 'Sure.' But, he was lovely." It was at this time that he may have concocted the story of the vision of his mother's dream to tell the world about the inspiration to the song "Let It Be."

While a good portion of the songs Paul composed in India during his stay in the early months of 1968 were well formed at that time or shortly thereafter, it appears that his vision of Mal Evans repeating the comforting words "let it be" "after many hours of uninterrupted meditation," as depicted in Kenneth Womack's book "Living The Beatles Legend: The Untold Story Of Mal Evans," didn't begin developing into a song until many months later. As brought out in this book, on August 21st, 1968 at EMI Studios during the recording of "Sexy Sadie," "Paul sat at the studio piano and regaled Mal with a snippet from 'Let It Be,' the dream song that he had begun composing back in Rishikesh. Paul had previously sung the tune's rudimentary lyrics to him...but this was different. For the roadie, it was thrilling to hear the then lines 'When I find myself in time of trouble, Mother Malcolm comes to me / whispers words of wisdom, let it be." While a good portion of the songs Paul composed in India during his stay in the early months of 1968 were well formed at that time or shortly thereafter, it appears that his vision of Mal Evans repeating the comforting words "let it be" "after many hours of uninterrupted meditation," as depicted in Kenneth Womack's book "Living The Beatles Legend: The Untold Story Of Mal Evans," didn't begin developing into a song until many months later. As brought out in this book, on August 21st, 1968 at EMI Studios during the recording of "Sexy Sadie," "Paul sat at the studio piano and regaled Mal with a snippet from 'Let It Be,' the dream song that he had begun composing back in Rishikesh. Paul had previously sung the tune's rudimentary lyrics to him...but this was different. For the roadie, it was thrilling to hear the then lines 'When I find myself in time of trouble, Mother Malcolm comes to me / whispers words of wisdom, let it be."

The above events can also be corroborated by the rough early demo of the song that Paul led The Beatles through on September 5th, 1968, in-between takes of recording “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.” During this early impromptu rendition, which was featured in the “Super Deluxe” 50th Anniversary “White Album” box set, we hear Paul twice sing “Mother Malcolm comes to me” instead of “Mother Mary,” just as Mal Evans described. This could easily lead one to challenge whether Paul's recollections about the dream of his mother telling him to “let it be” was accurate or not. It's amazing how the mind can sometimes convince us of something that may, in fact, not have happened, such as Paul receiving a dream of his mother when it was in actuality was about Mal Evans! In any event, it appears that the beginnings of the composition of the song "Let It Be" was during Paul's stay in India between February 20th and March 26th, 1968. The above events can also be corroborated by the rough early demo of the song that Paul led The Beatles through on September 5th, 1968, in-between takes of recording “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.” During this early impromptu rendition, which was featured in the “Super Deluxe” 50th Anniversary “White Album” box set, we hear Paul twice sing “Mother Malcolm comes to me” instead of “Mother Mary,” just as Mal Evans described. This could easily lead one to challenge whether Paul's recollections about the dream of his mother telling him to “let it be” was accurate or not. It's amazing how the mind can sometimes convince us of something that may, in fact, not have happened, such as Paul receiving a dream of his mother when it was in actuality was about Mal Evans! In any event, it appears that the beginnings of the composition of the song "Let It Be" was during Paul's stay in India between February 20th and March 26th, 1968.

Concerning the song's title, Paul relates in his book "The Lyrics" that this may have been a subliminal recollection from his past. "One interesting thing about 'Let It Be' that I was reminded of only recently is that, while I was studying English literature at the Liverpool Institute High School for Boys with my favorite teacher, Alan Durband, I read 'Hamlet.' In those days you had to learn speeches by heart because you had to be able to carry them into the exam and quote them. There are a couple of lines from late in the play: 'O, I could tell you - But let it be. - Horatio, I am dead." I suspect those lines had subconsciously planted themselves in my memory." Concerning the song's title, Paul relates in his book "The Lyrics" that this may have been a subliminal recollection from his past. "One interesting thing about 'Let It Be' that I was reminded of only recently is that, while I was studying English literature at the Liverpool Institute High School for Boys with my favorite teacher, Alan Durband, I read 'Hamlet.' In those days you had to learn speeches by heart because you had to be able to carry them into the exam and quote them. There are a couple of lines from late in the play: 'O, I could tell you - But let it be. - Horatio, I am dead." I suspect those lines had subconsciously planted themselves in my memory."

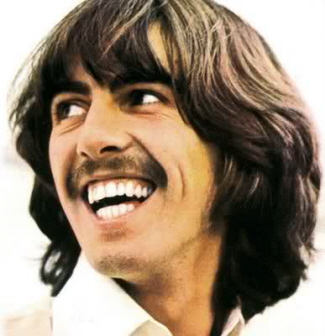

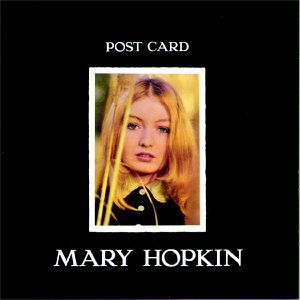

At any rate, Paul chose to present the song with a gospel flare, although his upbringing was anything but religious. “My mother was Catholic,” Paul relates in “Many Years From Now,” “and she had me and my brother christened but that was the only religious thing we went through other than school, and occasional visits to church, where I sang in a surpliced choir.” During rehearsals of the song on January 9th, 1969, George Harrison suggested that, since it had a gospel feel, Paul should present it to Aretha Franklin for her to record. "Do it AND give it to her," Paul responded. "As soon as we've got it, then we should get the tapes and do a rough demo when it's the first rehearsal. It'd be great for Aretha Franklin, that number." In the book contained in the Anniversary edition of the album "Let It Be," Paul elaborated: "What I used to like to do was think who would I really like to do this so, if we weren't jealously guarding a song for some reason, I would get an early version to people I would love to record it. I sent 'Let It Be' to Aretha Franklin." This resulted in her rendition of the song being included on her “This Girl's In Love With You” album that was released on January 15th, 1970, nearly two months prior to The Beatles' released version. At any rate, Paul chose to present the song with a gospel flare, although his upbringing was anything but religious. “My mother was Catholic,” Paul relates in “Many Years From Now,” “and she had me and my brother christened but that was the only religious thing we went through other than school, and occasional visits to church, where I sang in a surpliced choir.” During rehearsals of the song on January 9th, 1969, George Harrison suggested that, since it had a gospel feel, Paul should present it to Aretha Franklin for her to record. "Do it AND give it to her," Paul responded. "As soon as we've got it, then we should get the tapes and do a rough demo when it's the first rehearsal. It'd be great for Aretha Franklin, that number." In the book contained in the Anniversary edition of the album "Let It Be," Paul elaborated: "What I used to like to do was think who would I really like to do this so, if we weren't jealously guarding a song for some reason, I would get an early version to people I would love to record it. I sent 'Let It Be' to Aretha Franklin." This resulted in her rendition of the song being included on her “This Girl's In Love With You” album that was released on January 15th, 1970, nearly two months prior to The Beatles' released version.

Lyrically, Paul extended the subject matter beyond the problems within The Beatles to the world in general, “Let It Be” becoming a song of hope for the downtrodden. “The broken hearted people” who “may be parted” from loved ones, possibly in death, can be encouraged that “there will be an answer” of comfort, possibly alluding to the afterlife or heaven. The “light that shines on me” can either be interpreted as faith and hope in this life or the light that is commonly referred to as being seen during near-death experiences. Either way, the lyrics are left vague enough to remain open to interpretation, which is characteristic of a well-written song that everyone can relate to, regardless of race, creed or ideology. Lyrically, Paul extended the subject matter beyond the problems within The Beatles to the world in general, “Let It Be” becoming a song of hope for the downtrodden. “The broken hearted people” who “may be parted” from loved ones, possibly in death, can be encouraged that “there will be an answer” of comfort, possibly alluding to the afterlife or heaven. The “light that shines on me” can either be interpreted as faith and hope in this life or the light that is commonly referred to as being seen during near-death experiences. Either way, the lyrics are left vague enough to remain open to interpretation, which is characteristic of a well-written song that everyone can relate to, regardless of race, creed or ideology.

The reference to “Mother Mary” appears to have been inserted intentionally for this very reason. “'Mother Mary' makes it a quasi-religious thing,” Paul continues in “Many Years From Now,” "so you can take it that way. I don't mind. I'm quite happy if people want to use it to shore up their faith. I have no problem with that. I think it's a great thing to have faith of any sort, particularly in the world we live in...Looking back on all the Beatles' work, I'm very glad that most of it was positive and has been a positive force. I always find it very fortunate that most of our songs were to do with peace and love, and encourage people to do better and to have a better life. When you come to do these songs in places like the stadium in Santiago where all the dissidents were rounded up, I'm very glad to have these songs because they're such symbols of optimism and hopefulness." In "The Lyrics," Paul adds: "So, this song becomes a prayer, or mini-prayer. There's a yearning somewhere at its heart. And the word 'amen' itself means 'so be it' - or 'let it be.'" The reference to “Mother Mary” appears to have been inserted intentionally for this very reason. “'Mother Mary' makes it a quasi-religious thing,” Paul continues in “Many Years From Now,” "so you can take it that way. I don't mind. I'm quite happy if people want to use it to shore up their faith. I have no problem with that. I think it's a great thing to have faith of any sort, particularly in the world we live in...Looking back on all the Beatles' work, I'm very glad that most of it was positive and has been a positive force. I always find it very fortunate that most of our songs were to do with peace and love, and encourage people to do better and to have a better life. When you come to do these songs in places like the stadium in Santiago where all the dissidents were rounded up, I'm very glad to have these songs because they're such symbols of optimism and hopefulness." In "The Lyrics," Paul adds: "So, this song becomes a prayer, or mini-prayer. There's a yearning somewhere at its heart. And the word 'amen' itself means 'so be it' - or 'let it be.'"

Even though this is considered a “Lennon / McCartney” composition, John has distanced himself from “Let It Be.” “That's Paul's totally,” he told Playboy magazine in 1980. “It had nothing to do with The Beatles. It could have been Wings. I think he was inspired by 'Bridge Over Troubled Water.' He wanted to write one...I don't know what he's thinking when he writes 'Let It Be.'” This Simon & Garfunkel song wasn't released until nearly one-and-a-half years after “Let It Be” was written, but John's point is well taken. Lennon desired the January 1969 sessions to produce “fast ones,” referring to rock and roll songs as they had been known to perform in their early years. Even though this is considered a “Lennon / McCartney” composition, John has distanced himself from “Let It Be.” “That's Paul's totally,” he told Playboy magazine in 1980. “It had nothing to do with The Beatles. It could have been Wings. I think he was inspired by 'Bridge Over Troubled Water.' He wanted to write one...I don't know what he's thinking when he writes 'Let It Be.'” This Simon & Garfunkel song wasn't released until nearly one-and-a-half years after “Let It Be” was written, but John's point is well taken. Lennon desired the January 1969 sessions to produce “fast ones,” referring to rock and roll songs as they had been known to perform in their early years.

Recording History

The first appearance of the newly written “Let It Be” in the recording studio was on September 5th, 1968, as mentioned above. While perfecting George's “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” in EMI Studio Two with Eric Clapton present as lead guitarist, Paul took advantage of some downtime between takes to fool around with “Let It Be.” Engineer John Smith, not knowing how to identify this amusing new ad lib, simply wrote “Ad Lib” on the tape box. The first appearance of the newly written “Let It Be” in the recording studio was on September 5th, 1968, as mentioned above. While perfecting George's “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” in EMI Studio Two with Eric Clapton present as lead guitarist, Paul took advantage of some downtime between takes to fool around with “Let It Be.” Engineer John Smith, not knowing how to identify this amusing new ad lib, simply wrote “Ad Lib” on the tape box.

Paul wasn't bothering to teach them the chords or officially run them through a true rehearsal of the song at this time since the focus of that session was to give George's composition the attention it deserved. George specifically invited Eric Clapton on that day because he felt his bandmates weren't focused enough to record his song properly. If Paul would have started taking over the session by seriously leading The Beatles through a new song he had just written in the last few days, George possibly would have been even more perturbed. Paul wasn't bothering to teach them the chords or officially run them through a true rehearsal of the song at this time since the focus of that session was to give George's composition the attention it deserved. George specifically invited Eric Clapton on that day because he felt his bandmates weren't focused enough to record his song properly. If Paul would have started taking over the session by seriously leading The Beatles through a new song he had just written in the last few days, George possibly would have been even more perturbed.

In fact, when George witnessed Eric joining in on guitar for this ad lib of Paul's new song, he reeled everyone back in for the task at hand. George broke up the ad lib of “Let It Be” by saying, “Should we do one just a slight slower? Ok, roll it Ken (Scott), roll it. Make a note of this one 'cause this is the one. Cans on, Eric!” Shortly after Eric Clapton proceeded to put his headphones back on, they recorded the definitive rhythm track for “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” as we've come to know it. In fact, when George witnessed Eric joining in on guitar for this ad lib of Paul's new song, he reeled everyone back in for the task at hand. George broke up the ad lib of “Let It Be” by saying, “Should we do one just a slight slower? Ok, roll it Ken (Scott), roll it. Make a note of this one 'cause this is the one. Cans on, Eric!” Shortly after Eric Clapton proceeded to put his headphones back on, they recorded the definitive rhythm track for “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” as we've come to know it.

The instrumentation on this embryonic rehearsal of “Let It Be” was Paul on piano and lead vocals, John on organ and backing vocals (humorously repeating the phrase “let it be” in imitation of Paul), Ringo on drums and Eric Clapton fumbling through some lead guitar lines. Paul's lyrics went as far as including the lines “When I find myself in times of trouble / Brother Malcolm comes to me / whispering words of wisom / let it be.” As detailed above, this is a reference to Beatles associate Mal Evans, this lyrical insertion being remembered by the other Beatles in later months when they were officially working on the song. The instrumentation on this embryonic rehearsal of “Let It Be” was Paul on piano and lead vocals, John on organ and backing vocals (humorously repeating the phrase “let it be” in imitation of Paul), Ringo on drums and Eric Clapton fumbling through some lead guitar lines. Paul's lyrics went as far as including the lines “When I find myself in times of trouble / Brother Malcolm comes to me / whispering words of wisom / let it be.” As detailed above, this is a reference to Beatles associate Mal Evans, this lyrical insertion being remembered by the other Beatles in later months when they were officially working on the song.

Then, two weeks later, on September 19th, 1968, The Beatles were in EMI Studio One recording George's song “Piggies” when “Let It Be” was heard for the second time. “There were a couple of other songs around at the time,” producer Chris Thomas recounts in the book “The Beatles Recording Sessions.” “Paul was running through 'Let It Be' between takes.” McCartney had apparently fleshed out a little more of the lyrics in the past two weeks and thought to play through it on piano during a lull in the session. He apparently didn't feel comfortable enough with the song for inclusion on the “White Album,” unlike “Martha My Dear,” which was written and quickly recorded in October of 1968 for inclusion on the LP. Then, two weeks later, on September 19th, 1968, The Beatles were in EMI Studio One recording George's song “Piggies” when “Let It Be” was heard for the second time. “There were a couple of other songs around at the time,” producer Chris Thomas recounts in the book “The Beatles Recording Sessions.” “Paul was running through 'Let It Be' between takes.” McCartney had apparently fleshed out a little more of the lyrics in the past two weeks and thought to play through it on piano during a lull in the session. He apparently didn't feel comfortable enough with the song for inclusion on the “White Album,” unlike “Martha My Dear,” which was written and quickly recorded in October of 1968 for inclusion on the LP.

Three-and-a-half months went by before Paul considered “Let It Be” ready for proper consideration to be recorded by The Beatles. He corralled his band-mates together in January of 1969 for a month of filmed rehearsals and recording sessions, this as-yet-to-be-named project eventually being released under the title “Let It Be.” The rehearsals commenced at Twickenham Film Studios in London, the purpose being for each of the band members to bring forward newly written material to be rehearsed and arranged for a future live appearance, wherever they decided that would be. Three-and-a-half months went by before Paul considered “Let It Be” ready for proper consideration to be recorded by The Beatles. He corralled his band-mates together in January of 1969 for a month of filmed rehearsals and recording sessions, this as-yet-to-be-named project eventually being released under the title “Let It Be.” The rehearsals commenced at Twickenham Film Studios in London, the purpose being for each of the band members to bring forward newly written material to be rehearsed and arranged for a future live appearance, wherever they decided that would be.

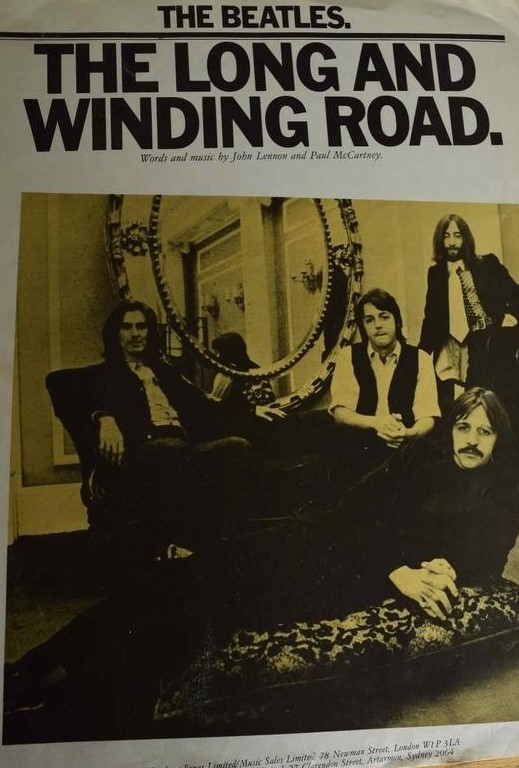

The second day of these rehearsals was on January 3rd, 1969, Paul being the first to arrive. While waiting for the others to get there, he ran through a few of his newly written compositions on piano, such as “The Long And Winding Road,” “Oh! Darling” and “Maxwell's Silver Hammer.” After some other piano exercises, including a medley that included "Tea For Two," "Whole Lotta Shakin' Going On" and the theme song to the British children's television show “Torchy, The Battery Boy,” Paul resurrected “Let It Be” as a mostly-written song that could possibly be worked out at this time. The second day of these rehearsals was on January 3rd, 1969, Paul being the first to arrive. While waiting for the others to get there, he ran through a few of his newly written compositions on piano, such as “The Long And Winding Road,” “Oh! Darling” and “Maxwell's Silver Hammer.” After some other piano exercises, including a medley that included "Tea For Two," "Whole Lotta Shakin' Going On" and the theme song to the British children's television show “Torchy, The Battery Boy,” Paul resurrected “Let It Be” as a mostly-written song that could possibly be worked out at this time.

He made it through the first verse and chorus of the song with the recently arriving Ringo looking on. Paul had by this time given “Let It Be” its gospel feel and its “Mother Mary” line, one slight difference in the lyric being “and in my darkest hour” instead of “in my hour of darkness” as on the released version. After this minute-long rendition, attention was then given to two newly written songs by Ringo, “Taking A Trip To Carolina” and “Picasso,” neither of these ever being worked out by the band. Once George and John arrived on that day, they gave detailed attention to George's “All Things Must Pass” and John's “Don't Let Me Down,” along with running through old Beatles material and impromptu cover songs. He made it through the first verse and chorus of the song with the recently arriving Ringo looking on. Paul had by this time given “Let It Be” its gospel feel and its “Mother Mary” line, one slight difference in the lyric being “and in my darkest hour” instead of “in my hour of darkness” as on the released version. After this minute-long rendition, attention was then given to two newly written songs by Ringo, “Taking A Trip To Carolina” and “Picasso,” neither of these ever being worked out by the band. Once George and John arrived on that day, they gave detailed attention to George's “All Things Must Pass” and John's “Don't Let Me Down,” along with running through old Beatles material and impromptu cover songs.

While The Beatles worked extensively on other new material, Paul finally decided to officially introduce “Let It Be” to his band-mates five days later, January 8th, 1969, at Twickenham Studios. After a lot of attention had been heaped upon George's “I Me Mine,” this being the only day they actually worked on the song, as well as other new compositions, Paul played “Let It Be” on piano during an equipment set up in the earlier part of the day. Ringo joined in on drums for a bit, as did an uniterested John on guitar. Recognizing Paul's changing the lyrics from “Brother Malcolm” to “Mother Mary,” John suggested changing it back to a reference to their loyal assistant and former roadie. "Change it to 'Brother Friar Malcolm,' and then we'll do it," Lennon humorously exclaimed, adding, "Would be great. 'Brother Malcolm.'" Paul complied with this during the two renditions of the song they went through at this time, but only when it became obvious that it was a botched performance. While The Beatles worked extensively on other new material, Paul finally decided to officially introduce “Let It Be” to his band-mates five days later, January 8th, 1969, at Twickenham Studios. After a lot of attention had been heaped upon George's “I Me Mine,” this being the only day they actually worked on the song, as well as other new compositions, Paul played “Let It Be” on piano during an equipment set up in the earlier part of the day. Ringo joined in on drums for a bit, as did an uniterested John on guitar. Recognizing Paul's changing the lyrics from “Brother Malcolm” to “Mother Mary,” John suggested changing it back to a reference to their loyal assistant and former roadie. "Change it to 'Brother Friar Malcolm,' and then we'll do it," Lennon humorously exclaimed, adding, "Would be great. 'Brother Malcolm.'" Paul complied with this during the two renditions of the song they went through at this time, but only when it became obvious that it was a botched performance.

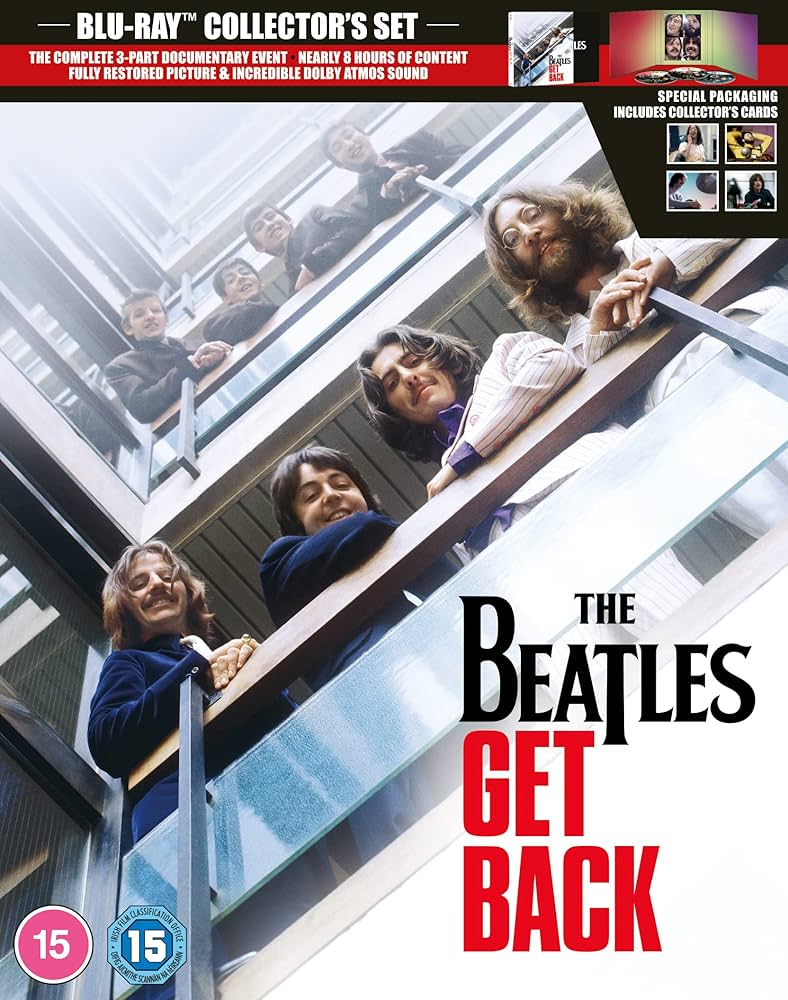

After a lunch break, they returned to “Let It Be” again, Paul calling out the chords to George during the performance. "You know the chords to 'Mother Mary,' don't you?" he asked George, the group affectionately referring to the song by this name throughout most of these January, 1969 sessions, as witnessed in the "Get Back" documentary series. They also began identifying the descending instrumental section of the song as "the F bit" on this day. Ringo began working out his drum part while John occasionally sang during the choruses. Alot of the lyrics were in place at this point, although the final verse was yet to be written. The Beatles had only scratched the surface of becoming acquainted with the song. After a lunch break, they returned to “Let It Be” again, Paul calling out the chords to George during the performance. "You know the chords to 'Mother Mary,' don't you?" he asked George, the group affectionately referring to the song by this name throughout most of these January, 1969 sessions, as witnessed in the "Get Back" documentary series. They also began identifying the descending instrumental section of the song as "the F bit" on this day. Ringo began working out his drum part while John occasionally sang during the choruses. Alot of the lyrics were in place at this point, although the final verse was yet to be written. The Beatles had only scratched the surface of becoming acquainted with the song.

On the next day of Twickenham rehearsals, January 9th, 1969, they went through “Let It Be” a total of sixteen times. One of the earlier rough run-throughs had Ringo playing a shuffle beat on drums at Paul's request, with John on acoustic guitar, George on lead electric guitar, and Paul on piano and lead vocal with audible demonstrations of what he envisioned for the guitar solo. John moved to the Fender Bass VI guitar shortly thereafter so as to keep with the no-overdubs policy they wanted to maintain throughout this project. In a later rendition that day with John on bass, Paul instructed John to sing backing “aaah”s during the choruses, the song sounding a little more cohesive at that point. On the next day of Twickenham rehearsals, January 9th, 1969, they went through “Let It Be” a total of sixteen times. One of the earlier rough run-throughs had Ringo playing a shuffle beat on drums at Paul's request, with John on acoustic guitar, George on lead electric guitar, and Paul on piano and lead vocal with audible demonstrations of what he envisioned for the guitar solo. John moved to the Fender Bass VI guitar shortly thereafter so as to keep with the no-overdubs policy they wanted to maintain throughout this project. In a later rendition that day with John on bass, Paul instructed John to sing backing “aaah”s during the choruses, the song sounding a little more cohesive at that point.

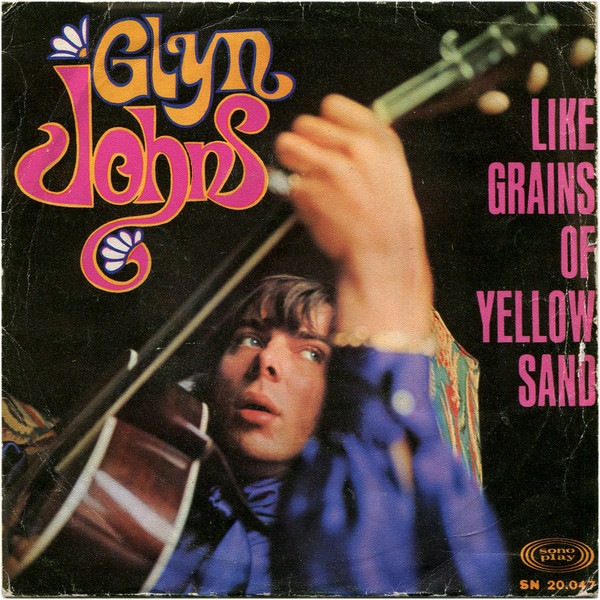

By the end of the rehearsals of the song on this day, the arrangement was much more refined and similar to what we have become familiar with. As seen in Peter Jackson's "Get Back" series, engineer Glyn Johns is playing a sizable part in arranging the song, instructing Paul how he feels 'the F bit' should appear in the song. "He seems to be arranging this," Paul slyly remarks to the others about Glyn's input, which they all appear to respect and continue to listen to. Paul plays and sings the first verse by himself, John and George supply backing vocals during the first chorus, which consist of "aaah"s but then move to harmonizing "whisper words of wisdom, let it be." Ringo joins in on kick drum and tambourine during the next verse and rolls into the following chorus, which has him play a steady rock beat while riding on his hi-hat. One of these rehearsals contain George humorously singing "Speaking Norman Wilson." That second chorus also has John join in on bass, the instrumental break that follows including a guitar solo from George and backing vocals by Paul, John and George. Paul still hasn't completed the lyrics in the last set of verses, so ad libs such as “read the Record Mirror, let it be” are heard during these rehearsals. By the end of the rehearsals of the song on this day, the arrangement was much more refined and similar to what we have become familiar with. As seen in Peter Jackson's "Get Back" series, engineer Glyn Johns is playing a sizable part in arranging the song, instructing Paul how he feels 'the F bit' should appear in the song. "He seems to be arranging this," Paul slyly remarks to the others about Glyn's input, which they all appear to respect and continue to listen to. Paul plays and sings the first verse by himself, John and George supply backing vocals during the first chorus, which consist of "aaah"s but then move to harmonizing "whisper words of wisdom, let it be." Ringo joins in on kick drum and tambourine during the next verse and rolls into the following chorus, which has him play a steady rock beat while riding on his hi-hat. One of these rehearsals contain George humorously singing "Speaking Norman Wilson." That second chorus also has John join in on bass, the instrumental break that follows including a guitar solo from George and backing vocals by Paul, John and George. Paul still hasn't completed the lyrics in the last set of verses, so ad libs such as “read the Record Mirror, let it be” are heard during these rehearsals.

Paul was the first to arrive at Twickenham the following day, January 10th, 1969, so he ran through a few recent compositions on piano for music publisher Dick James, including “Let It Be.” Tensions ran quite high after the other Beatles arrived, resulting in George actually quitting the band during their lunch break. With the future of the project, as well as The Beatles as a whole, in question, the following two rehearsals without George were largely unproductive and didn't include any attempts at running through the song “Let It Be.” Paul was the first to arrive at Twickenham the following day, January 10th, 1969, so he ran through a few recent compositions on piano for music publisher Dick James, including “Let It Be.” Tensions ran quite high after the other Beatles arrived, resulting in George actually quitting the band during their lunch break. With the future of the project, as well as The Beatles as a whole, in question, the following two rehearsals without George were largely unproductive and didn't include any attempts at running through the song “Let It Be.”

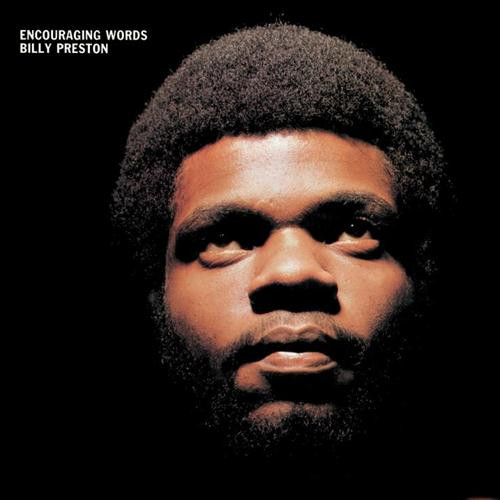

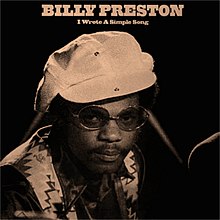

Upon George's return to The Beatles, an agreement was made to move the rehearsals to their basement studio at their Apple Building at 3 Savile Row in London. Their January 23rd, 1969 session at this new location witnessed Paul sneaking in two piano renditions of “Let It Be” for guest keyboardist Billy Preston to hear and get acquainted with. No band rehearsals of the song occurred on this day, however. Upon George's return to The Beatles, an agreement was made to move the rehearsals to their basement studio at their Apple Building at 3 Savile Row in London. Their January 23rd, 1969 session at this new location witnessed Paul sneaking in two piano renditions of “Let It Be” for guest keyboardist Billy Preston to hear and get acquainted with. No band rehearsals of the song occurred on this day, however.

Even though Billy Preston was not present at their January 25th, 1969 session at Apple Studios, Paul thought to run through “Let It Be” again to reaquaint himself and his band-mates with the arrangement they came up with a little over two weeks prior. Even though this session had been very productive, their nailing down the near perfect recording of "For You Blue" and making the decision to perform the project's "pay-off" concert on the roof, they still decided to rehearse "Let It Be" a total of 18 times to maybe even get an acceptable proper recording of it before they left for the day. However, this process wasn't all fun and games!

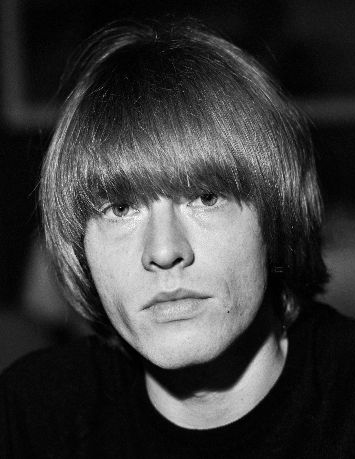

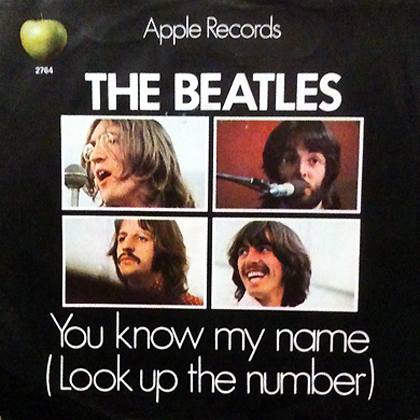

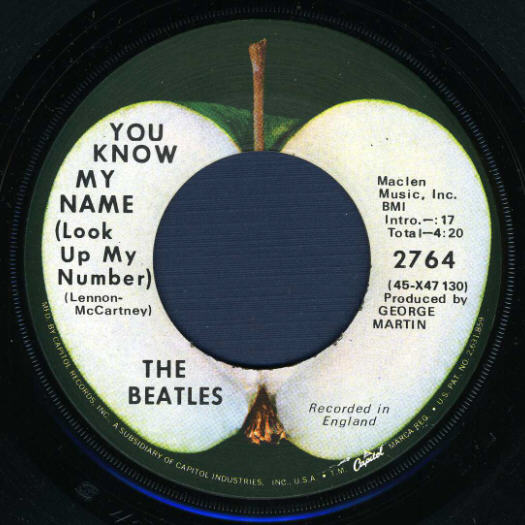

The earlier run-throughs of “Let It Be” on this day showed they had either forgotten their parts or just weren't into it, John in particular apparently not really remembering the song's existence at all. When he asked whether he had rehearsed the song with the group earlier, George reminded him that he played bass. "Bass?!" he exclaimed, adding, "I'm getting like Brian Jones in this group! You just give me the instrument, Paul, and I'll give you something!" Rolling Stones guitarist Brian Jones had become known for playing many instruments other than guitar on their recordings, as well as having played saxophone on The Beatles' "You Know My Name (Look Up The Number)," which would eventually be released as the b-side to "Let It Be" the following year. John's bass playing, however, was full of flubs, not to mention Ringo's drum part not being perfected yet, and John and George's backing vocals being erratic and too loud. The earlier run-throughs of “Let It Be” on this day showed they had either forgotten their parts or just weren't into it, John in particular apparently not really remembering the song's existence at all. When he asked whether he had rehearsed the song with the group earlier, George reminded him that he played bass. "Bass?!" he exclaimed, adding, "I'm getting like Brian Jones in this group! You just give me the instrument, Paul, and I'll give you something!" Rolling Stones guitarist Brian Jones had become known for playing many instruments other than guitar on their recordings, as well as having played saxophone on The Beatles' "You Know My Name (Look Up The Number)," which would eventually be released as the b-side to "Let It Be" the following year. John's bass playing, however, was full of flubs, not to mention Ringo's drum part not being perfected yet, and John and George's backing vocals being erratic and too loud.

George, who was playing his psychedelic-painted Stratocaster, asks "Paul, How does it start?" After Paul replies, "I don't know," he begins playing piano and singing the first verse, which prompts George's response, "So just straight in at the first verse as an intro?" Quickly thereafter, they decide to begin the song with the "F bit" as detailed above. Recognizing their disinterest in the song, Paul exorts, “OK, you watch us, we're gonna do this now. Ok boy, now, come on. Pull yourselves together!” John replies, “You talkin' to me?” George then responds by beginning an impromptu rendition of Chuck Berry's “I'm Talking About You,” which is then squashed by Paul who wants to get back to the business at hand. “Come on now,” he interjects, “back to the drudgery.” John angrily responds, “It's you that's bloody making it like this!” Paul sarcastically comes back with “The real meaning of Christmas” before beginning another rendition of “Let It Be,” the next few rehearsals of the song sounding very mediocre. George, who was playing his psychedelic-painted Stratocaster, asks "Paul, How does it start?" After Paul replies, "I don't know," he begins playing piano and singing the first verse, which prompts George's response, "So just straight in at the first verse as an intro?" Quickly thereafter, they decide to begin the song with the "F bit" as detailed above. Recognizing their disinterest in the song, Paul exorts, “OK, you watch us, we're gonna do this now. Ok boy, now, come on. Pull yourselves together!” John replies, “You talkin' to me?” George then responds by beginning an impromptu rendition of Chuck Berry's “I'm Talking About You,” which is then squashed by Paul who wants to get back to the business at hand. “Come on now,” he interjects, “back to the drudgery.” John angrily responds, “It's you that's bloody making it like this!” Paul sarcastically comes back with “The real meaning of Christmas” before beginning another rendition of “Let It Be,” the next few rehearsals of the song sounding very mediocre.

The atmosphere then becomes silly as proposed lyrics for the unwritten third verse are suggested. "Captain Marvel comes to me," George proposes, while John adds, "Bloody Mary comes to me." Art dealer Robert Fraser stops in during this session, which prompts Paul to sing, "and here's to Robert Fraser...," to which John continues, "...from his gallery!" During a piano intro on another runthrough, John states, "I'd especially like to thank you for all the birthday presents," this being a recollection of the Christmas message recordings The Beatles had been making to their fans. The atmosphere then becomes silly as proposed lyrics for the unwritten third verse are suggested. "Captain Marvel comes to me," George proposes, while John adds, "Bloody Mary comes to me." Art dealer Robert Fraser stops in during this session, which prompts Paul to sing, "and here's to Robert Fraser...," to which John continues, "...from his gallery!" During a piano intro on another runthrough, John states, "I'd especially like to thank you for all the birthday presents," this being a recollection of the Christmas message recordings The Beatles had been making to their fans.

Paul then decides to think positive and instructs producer Glyn Johns to properly record the next take, hoping to possibly nail down another perfect recording for the project on this day. “This here's gonna knock you out,” he states, leading the group through the version that was included on the 1996 released “Anthology 3.” This excellent rendition features great piano and vocal work from Paul, despite the fact that the lyrics in the final verses were yet to be written. Ringo stopped playing during these final verses but otherwise put in a subdued but adequate performance. John and George's backing “aaah”s were done well as was George's lead guitar solo, which was goaded on by Paul with an appropriate “yeah” during its opening measure. The composer adds in a couple exclamations of “let it be” during the final chords, indicating that he was well pleased with the outcome of this take. They did go through the song a few more times after this, including a fast rock 'n' roll version, but because of lack of interest and low energy, these were half-hearted at best. "Can we carry this on tomorrow?", Paul asks, which ends the session for the day. Paul then decides to think positive and instructs producer Glyn Johns to properly record the next take, hoping to possibly nail down another perfect recording for the project on this day. “This here's gonna knock you out,” he states, leading the group through the version that was included on the 1996 released “Anthology 3.” This excellent rendition features great piano and vocal work from Paul, despite the fact that the lyrics in the final verses were yet to be written. Ringo stopped playing during these final verses but otherwise put in a subdued but adequate performance. John and George's backing “aaah”s were done well as was George's lead guitar solo, which was goaded on by Paul with an appropriate “yeah” during its opening measure. The composer adds in a couple exclamations of “let it be” during the final chords, indicating that he was well pleased with the outcome of this take. They did go through the song a few more times after this, including a fast rock 'n' roll version, but because of lack of interest and low energy, these were half-hearted at best. "Can we carry this on tomorrow?", Paul asks, which ends the session for the day.

Billy Preston was due to be present for the next day's rehearsal, January 26th, 1969 in their basement studio at Apple Headquarters, as was Linda Eastman and her daughter Heather, the youngster actually playing hi-hat with Ringo during rehearsals for the song "Let It Be" on this day. Paul was enthusiastic about seeing how Billy's Hammond organ contributions to “Let It Be” would work with The Beatles' performance but, since he was late in arriving, George Martin filled in on organ for the taped rehearsals on this day. "It's very country and western in a way," George Martin commented, which prompted John to exclaim, "Country and gospel, it is." When listening to a playback of a take in their control room, as seen in Peter Jackson's "Get Back" series, John suggests, "Do that old gospel ending," to which George humorously counters, "We'll all kneel as we do it." Billy Preston was due to be present for the next day's rehearsal, January 26th, 1969 in their basement studio at Apple Headquarters, as was Linda Eastman and her daughter Heather, the youngster actually playing hi-hat with Ringo during rehearsals for the song "Let It Be" on this day. Paul was enthusiastic about seeing how Billy's Hammond organ contributions to “Let It Be” would work with The Beatles' performance but, since he was late in arriving, George Martin filled in on organ for the taped rehearsals on this day. "It's very country and western in a way," George Martin commented, which prompted John to exclaim, "Country and gospel, it is." When listening to a playback of a take in their control room, as seen in Peter Jackson's "Get Back" series, John suggests, "Do that old gospel ending," to which George humorously counters, "We'll all kneel as we do it."

They still began each rendition with "the F bit" heard after the second chorus, deciding to repeat it twice on this day. Another refinement was instituted just before "take ten" on this day at George Harrison's suggestion, "Maybe just have one chorus on the first time and two choruses on the second time," Paul replying, "Ok, I think that's good." As heard in various Anniversary editions of the "Let It Be" album, Paul sings and plays a bit of "Please Please Me" on piano before starting off "take ten," John exclaiming, "That was daft, y'know!" When Paul kept delaying, John once again humorously complained, "C'mon, I only get two notes in this song!" The performance of "Let It Be" comes across well, George Martin's organ part being quite rudimentary probably due to his not having played it before this day. They still began each rendition with "the F bit" heard after the second chorus, deciding to repeat it twice on this day. Another refinement was instituted just before "take ten" on this day at George Harrison's suggestion, "Maybe just have one chorus on the first time and two choruses on the second time," Paul replying, "Ok, I think that's good." As heard in various Anniversary editions of the "Let It Be" album, Paul sings and plays a bit of "Please Please Me" on piano before starting off "take ten," John exclaiming, "That was daft, y'know!" When Paul kept delaying, John once again humorously complained, "C'mon, I only get two notes in this song!" The performance of "Let It Be" comes across well, George Martin's organ part being quite rudimentary probably due to his not having played it before this day.

One thing noticeable on this and all of the 28 rehearsals of the song on this day was the fact that Paul still hadn't written the lyrics to the final set of verses. After listening to a playback of a recording from the day before he stated, "I'll have to think of some more words. But that's all right, because if I do think of the right words then it'll tie it up." This led to amusing vocal ad libs, such as “You will be a good girl, let it be / and though you may be told off, you will still be able to see / that there must be an answer, let it be.” One thing noticeable on this and all of the 28 rehearsals of the song on this day was the fact that Paul still hadn't written the lyrics to the final set of verses. After listening to a playback of a recording from the day before he stated, "I'll have to think of some more words. But that's all right, because if I do think of the right words then it'll tie it up." This led to amusing vocal ad libs, such as “You will be a good girl, let it be / and though you may be told off, you will still be able to see / that there must be an answer, let it be.”

While Paul is instructing Ringo to "play it lighter" during the song's conclusion, George adlibs a third verse singing, "Somewhere in the heaven there he sees a man call Babragi / singing words of wisdom, let it be." This is immediately followed by John singing, "Somewhere out in Weybridge there's a cat who's name is Pavagi / singing words of wisdom, let it B, H, I, J, K." Paul later repeats John's lyric but changes the cat's name to "Banagy," continuing, "there will be the answer, let it be / and in my darkest hour, she is...,” George then interrupting with “...sitting on the lavatory,” causing John to repeat the phrase while laughing. Once Billy Preston arrived, Paul asked him to play "the F bit" like Bach. After his demonstration impressed everyone, Paul retorted, "Oh, look, that's all right. That'll do!" While Paul is instructing Ringo to "play it lighter" during the song's conclusion, George adlibs a third verse singing, "Somewhere in the heaven there he sees a man call Babragi / singing words of wisdom, let it be." This is immediately followed by John singing, "Somewhere out in Weybridge there's a cat who's name is Pavagi / singing words of wisdom, let it B, H, I, J, K." Paul later repeats John's lyric but changes the cat's name to "Banagy," continuing, "there will be the answer, let it be / and in my darkest hour, she is...,” George then interrupting with “...sitting on the lavatory,” causing John to repeat the phrase while laughing. Once Billy Preston arrived, Paul asked him to play "the F bit" like Bach. After his demonstration impressed everyone, Paul retorted, "Oh, look, that's all right. That'll do!"

Twleve more versions of “Let It Be” were performed with Billy Preston the following day, January 27th, 1969 at Apple Studios. The final arrangement was pretty set by this time, although they did some experimentation on this day. On some versions, George and John played some guitar and bass riffs during the early part of the song, while Billy experimented with some different organ parts, even substituting electric piano instead of organ. After one particular soulful electric piano rendition, Paul remarks, "Of course, coming from the North of England, it doesn't come through easy in all the soul," which prompts a laugh from Billy. George also took some time to work through a lead guitar part during the song's final chorus. Since Paul still didn't have the lyrics to the final set of verses written, he would sometimes sing scat vocals, John even adding what Bruce Spizer describes in his book “The Beatles On Apple Records” as “inappropriate vocal ad-libs, perhaps out of boredom.” Twleve more versions of “Let It Be” were performed with Billy Preston the following day, January 27th, 1969 at Apple Studios. The final arrangement was pretty set by this time, although they did some experimentation on this day. On some versions, George and John played some guitar and bass riffs during the early part of the song, while Billy experimented with some different organ parts, even substituting electric piano instead of organ. After one particular soulful electric piano rendition, Paul remarks, "Of course, coming from the North of England, it doesn't come through easy in all the soul," which prompts a laugh from Billy. George also took some time to work through a lead guitar part during the song's final chorus. Since Paul still didn't have the lyrics to the final set of verses written, he would sometimes sing scat vocals, John even adding what Bruce Spizer describes in his book “The Beatles On Apple Records” as “inappropriate vocal ad-libs, perhaps out of boredom.”

After the "f bit" is played in one rehearsal, as wtinessed in the "Get Back" documentary series, Paul states, "It's a bit ploddy." "What?" John asks, to which, Paul replies, "it just sorts of plods along a bit." John explains, "It's just morning and slow; and a slow song. It takes a long time to get out of it." Paul relented by saying, "That'll do for the time being" before moving on to "The Long And Winding Road," which he also wasn't feeling inspired by on this day. At any rate, with the time frame to complete the project nearing its end, all that was left was for Paul to complete the lyrics. Otherwise, everyone pretty much had their parts perfected. After the "f bit" is played in one rehearsal, as wtinessed in the "Get Back" documentary series, Paul states, "It's a bit ploddy." "What?" John asks, to which, Paul replies, "it just sorts of plods along a bit." John explains, "It's just morning and slow; and a slow song. It takes a long time to get out of it." Paul relented by saying, "That'll do for the time being" before moving on to "The Long And Winding Road," which he also wasn't feeling inspired by on this day. At any rate, with the time frame to complete the project nearing its end, all that was left was for Paul to complete the lyrics. Otherwise, everyone pretty much had their parts perfected.

It was on January 29th, 1969 that The Beatles decided that their live performance would be relegated to the Apple Headquarters roof the following day. The five songs that were deemed appropriate to be played on the roof were rehearsed on this day, the remainder of the session being used to work out all of the bugs on the other selections they felt were complete, “Let It Be” being among them. They only needed to go through the song once on this day, this lackluster performance being evidence that they were simply going through the motions on something they basically knew like the back of their hand. It was on January 29th, 1969 that The Beatles decided that their live performance would be relegated to the Apple Headquarters roof the following day. The five songs that were deemed appropriate to be played on the roof were rehearsed on this day, the remainder of the session being used to work out all of the bugs on the other selections they felt were complete, “Let It Be” being among them. They only needed to go through the song once on this day, this lackluster performance being evidence that they were simply going through the motions on something they basically knew like the back of their hand.

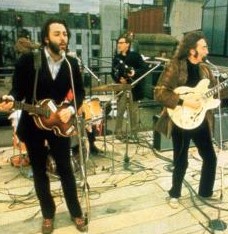

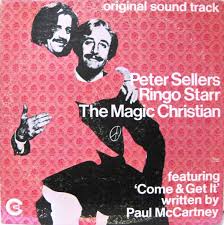

Their rooftop performance the following day, January 30th, 1969, went quite well, despite the cold weather and the threat from police to shut them down. With the filming of Ringo and Peter Sellers' movie “The Magic Christian” beginning in February, The Beatles had one remaining day to officially record and film the other three songs that they had perfected for this project, these being “The Long And Winding Road,” “Two Of Us” and "Let It Be." Of interest here is a conversation among The Beatles in the control room of Apple Studios on January 30th, 1969, as seen in Peter Jackson's "Get Back" series. Concerning the idea of performing "Let It Be" and the other songs not performed on the roof in their basement studio afterwards, George suggested, "We could pretend in the film that we had to get down because of (the police) and then here we are!" Their rooftop performance the following day, January 30th, 1969, went quite well, despite the cold weather and the threat from police to shut them down. With the filming of Ringo and Peter Sellers' movie “The Magic Christian” beginning in February, The Beatles had one remaining day to officially record and film the other three songs that they had perfected for this project, these being “The Long And Winding Road,” “Two Of Us” and "Let It Be." Of interest here is a conversation among The Beatles in the control room of Apple Studios on January 30th, 1969, as seen in Peter Jackson's "Get Back" series. Concerning the idea of performing "Let It Be" and the other songs not performed on the roof in their basement studio afterwards, George suggested, "We could pretend in the film that we had to get down because of (the police) and then here we are!"

Therefore, on January 31st, 1969, The Beatles assembled with George Martin and engineers Glyn Johns and Alan Parsons to record what was referred to on the tape box as the “Apple Studio Performance.” Various other songs were performed in between takes, such as “Lady Madonna,” “Run For Your Life” and even “Build Me Up Buttercup,” but the primary focus was the three compositions mentioned above that were deemed unsuitable for the rooftop performance. Since the proceedings were also being filmed for inclusion in what eventually became the “Let It Be” movie, the four Beatles and Billy Preston arranged themselves into stage formation around a platform, John insisting on sitting on the floor in front of the piano next to Yoko throughout the proceedings. Therefore, on January 31st, 1969, The Beatles assembled with George Martin and engineers Glyn Johns and Alan Parsons to record what was referred to on the tape box as the “Apple Studio Performance.” Various other songs were performed in between takes, such as “Lady Madonna,” “Run For Your Life” and even “Build Me Up Buttercup,” but the primary focus was the three compositions mentioned above that were deemed unsuitable for the rooftop performance. Since the proceedings were also being filmed for inclusion in what eventually became the “Let It Be” movie, the four Beatles and Billy Preston arranged themselves into stage formation around a platform, John insisting on sitting on the floor in front of the piano next to Yoko throughout the proceedings.

After The Beatles nailed down an acceptable performance of “Two Of Us,” as well as messing around with various other selections, Paul moved from acoustic guitar to piano to set their attention to “Let It Be.” They performed many takes of this song that were numbered takes 20 through 27 to coincide with the take numbers from the film's clapper board. Since there were a few breakdowns and false starts, some of these numbered takes included these incomplete versions along with full renditions of the song. Paul had finally written the lyrics to the final set of verses by this day, and had decided to introduce the song by playing an instrumental version of the verse on piano instead of "the F bit" as he had been. After The Beatles nailed down an acceptable performance of “Two Of Us,” as well as messing around with various other selections, Paul moved from acoustic guitar to piano to set their attention to “Let It Be.” They performed many takes of this song that were numbered takes 20 through 27 to coincide with the take numbers from the film's clapper board. Since there were a few breakdowns and false starts, some of these numbered takes included these incomplete versions along with full renditions of the song. Paul had finally written the lyrics to the final set of verses by this day, and had decided to introduce the song by playing an instrumental version of the verse on piano instead of "the F bit" as he had been.

A rehearsal of the song before the official takes began included a version played with a skiffle-style beat and Lennon singing the words to a different melody. It was obvious that John was becoming irritated and/or bored of the whole process by this point, making fun of the lyrics on occasion to releive some stress. “And in my hour of darkness, she is standing left in front of me,” he sings at one point, continuing, “squeaking turds of whiskey over me.” A rehearsal of the song before the official takes began included a version played with a skiffle-style beat and Lennon singing the words to a different melody. It was obvious that John was becoming irritated and/or bored of the whole process by this point, making fun of the lyrics on occasion to releive some stress. “And in my hour of darkness, she is standing left in front of me,” he sings at one point, continuing, “squeaking turds of whiskey over me.”

"Take 20" started off well but was called to a stop by Glyn Johns midway through the first chorus because Paul's vocals were popping, especially on the word “be.” John begins whistling when the signal to stop occurs and then mutters, “What the f*ck is going on?” and mentions the popping. “This isn't very loud, Glyn,” Paul complains, John interjecting, “Poppin's in, man. I'll never get 'Maggie Mae' done if it goes on like this!” After another false start, they deliver their first complete performance, flawed only by John flubbing his bass part during the descending chords just before the guitar solo, John announcing “F*cked it!" directly after his mistake. After the song concludes, John asks, “Let it be, eh?” After Paul answers, “Yeah,” John adds, “I know what you mean.” "Take 20" started off well but was called to a stop by Glyn Johns midway through the first chorus because Paul's vocals were popping, especially on the word “be.” John begins whistling when the signal to stop occurs and then mutters, “What the f*ck is going on?” and mentions the popping. “This isn't very loud, Glyn,” Paul complains, John interjecting, “Poppin's in, man. I'll never get 'Maggie Mae' done if it goes on like this!” After another false start, they deliver their first complete performance, flawed only by John flubbing his bass part during the descending chords just before the guitar solo, John announcing “F*cked it!" directly after his mistake. After the song concludes, John asks, “Let it be, eh?” After Paul answers, “Yeah,” John adds, “I know what you mean.”

"Take 21" started off fine but kept slowing in tempo, this prompting Paul to call the performance to a halt after the guitar solo. He then sang the line “When all the broken hearted people” as a slurring drunk, which causes John to call out “Get off, you bum!” in imitation of a heckler in a nightclub. Paul then states, “It just, I don't know, it got so, sort of...I don't know.” "Take 21" started off fine but kept slowing in tempo, this prompting Paul to call the performance to a halt after the guitar solo. He then sang the line “When all the broken hearted people” as a slurring drunk, which causes John to call out “Get off, you bum!” in imitation of a heckler in a nightclub. Paul then states, “It just, I don't know, it got so, sort of...I don't know.”

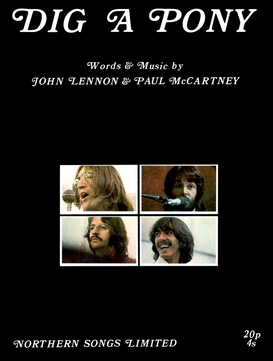

"Take 22" was a complete performance but was also marred by a slowing tempo. When Paul realized this wasn't going to be the final take, he sang the last verse as “When I find myself in times of heartache, Brother Malcolm comes to me,” and then finishes the take in a less-than-serious vocal tone. After it concludes, John sings, “There once was a woman / that loved a moondog.” “Moondog,” of course, was a reference to an early name for The Beatles and was also included in the lyrics to John's “Dig A Pony” from these January 1969 sessions. "Take 22" was a complete performance but was also marred by a slowing tempo. When Paul realized this wasn't going to be the final take, he sang the last verse as “When I find myself in times of heartache, Brother Malcolm comes to me,” and then finishes the take in a less-than-serious vocal tone. After it concludes, John sings, “There once was a woman / that loved a moondog.” “Moondog,” of course, was a reference to an early name for The Beatles and was also included in the lyrics to John's “Dig A Pony” from these January 1969 sessions.

Before "take 23" begins, John states, “Daddy wants to wee wee,” which triggers Paul to announce, “Daddy wants wee wee, Glyn!” After "take 23" is announced, Paul says, “Keep it going, leave it up a bit or something.” John then states, “Don't say that word,” which Paul answers with “a-a-a-a-awful sorry!” John then asks with mock sincerity, “Are we supposed to giggle in the solo?” to which Paul replies, “yeah,” followed by John's “okay.” This take went quite well, although after it was over John stated in a British royalty accent, “I lost a bass note somewhere!” After Paul replies “Oh!” in a similar accent, John continues, “I don't think it mattered if that was it.” Before "take 23" begins, John states, “Daddy wants to wee wee,” which triggers Paul to announce, “Daddy wants wee wee, Glyn!” After "take 23" is announced, Paul says, “Keep it going, leave it up a bit or something.” John then states, “Don't say that word,” which Paul answers with “a-a-a-a-awful sorry!” John then asks with mock sincerity, “Are we supposed to giggle in the solo?” to which Paul replies, “yeah,” followed by John's “okay.” This take went quite well, although after it was over John stated in a British royalty accent, “I lost a bass note somewhere!” After Paul replies “Oh!” in a similar accent, John continues, “I don't think it mattered if that was it.”

"Take 24" was going quite well right into the guitar solo section where George ad-libs impressively, Paul singing encouragingly “Let it be, yeah, whoah.” Paul then accidentally leads the band through two choruses instead of just one, a mistake he would typically make. Since there are two choruses at the end of the song, John mistook this to be the conclusion and started playing the descending bass pattern heard at the song's end. As Paul notices this when he begins the final set of verses, he reacts vocally with “When I find myself in, whoah!” Billy Preston reacts to this flub with some soulful swirling organ playing, knowing that this take was ruined. Paul continues on nonetheless, singing in an exagerated style until John stops the take by exclaiming, “OK, OK,” Paul continuing with, “OK, she stands right in...” until everybody stops playing. “I thought it was 'end,' you know,” John apologetically states regarding his bass flub. "Take 24" was going quite well right into the guitar solo section where George ad-libs impressively, Paul singing encouragingly “Let it be, yeah, whoah.” Paul then accidentally leads the band through two choruses instead of just one, a mistake he would typically make. Since there are two choruses at the end of the song, John mistook this to be the conclusion and started playing the descending bass pattern heard at the song's end. As Paul notices this when he begins the final set of verses, he reacts vocally with “When I find myself in, whoah!” Billy Preston reacts to this flub with some soulful swirling organ playing, knowing that this take was ruined. Paul continues on nonetheless, singing in an exagerated style until John stops the take by exclaiming, “OK, OK,” Paul continuing with, “OK, she stands right in...” until everybody stops playing. “I thought it was 'end,' you know,” John apologetically states regarding his bass flub.

"Take 25" just makes it through to the first chorus where Paul starts singing in a high falsetto harmony on top of John and George's “aaah”s. This prompts Paul to exclaim, “What the sh*t and hell is going on here?” John and Paul then engage in some pseudo-German banter before Paul continues into a second attempt at "take 25" by counting it off in a mock German accent. This next rendition makes it all the way to the end but was determined mid-way through to be spurious, resulting in Paul once again including “Brother Malcolm” in the lyrics. After it concludes, the following conversation takes place: "Take 25" just makes it through to the first chorus where Paul starts singing in a high falsetto harmony on top of John and George's “aaah”s. This prompts Paul to exclaim, “What the sh*t and hell is going on here?” John and Paul then engage in some pseudo-German banter before Paul continues into a second attempt at "take 25" by counting it off in a mock German accent. This next rendition makes it all the way to the end but was determined mid-way through to be spurious, resulting in Paul once again including “Brother Malcolm” in the lyrics. After it concludes, the following conversation takes place:

John (sarcastically): “I think that was rather grand. I'd take one home with me.”

Glyn: “No, that was fine.”

John (mimicking the computer HAL9000 from the movie “2001: A Space Odyssey”): Don't kid us, Glyn. Give it to us straight.”

Glyn: "That was straight."

Paul: “Ah, what do you think, Glyn?”

Glyn: “I don't think it's yet.”

Paul: “C'mon.”

John: “OK, let's track it. (Sharply intakes breath creating a sound of shock.) You bounder, you cheat!” (and then reprising “2001: A Space Odyssey”) “Get Me Off This Base! Get Me Off...”