Search by Keyword

|

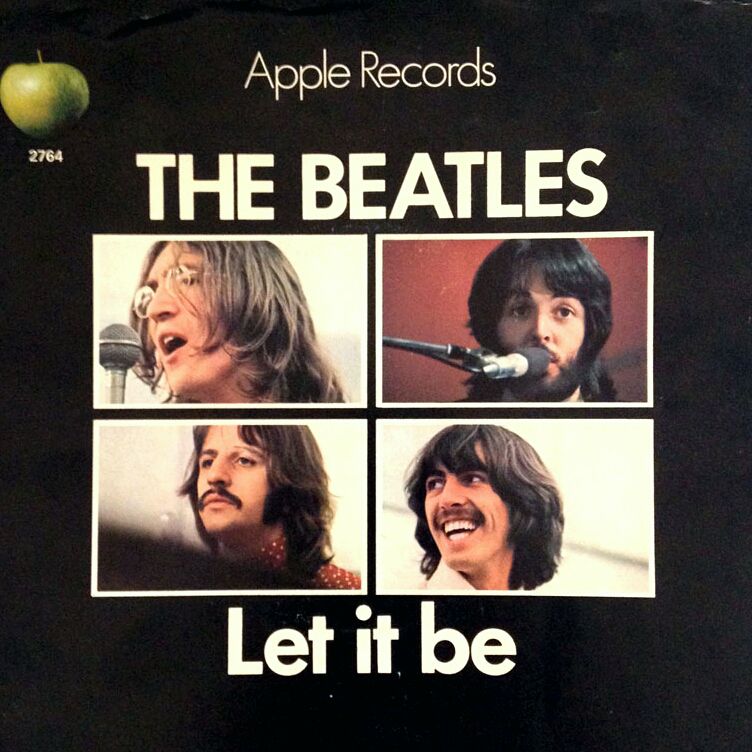

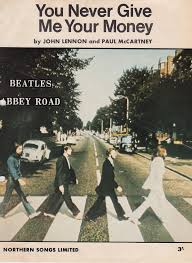

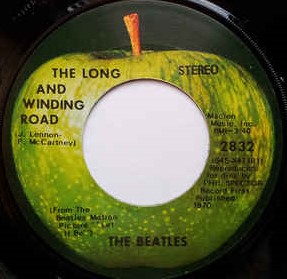

“THE LONG AND WINDING ROAD”

(John Lennon – Paul McCartney)

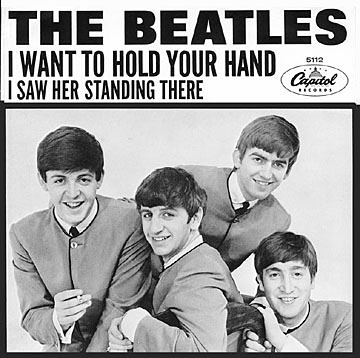

In 1964 when The Beatles broke onto the scene in America, they seemed to be able to do no wrong as far as hit singles were concerned. “I Want To Hold Your Hand” raced up to the #1 spot on the US Billboard Hot 100, staying there for an amazing seven weeks. From that point on, nearly every new official Beatles release reached the top spot on this chart, as did some unofficial singles such as “Eight Days A Week” and “Yesterday.” Any record label that had license to do so released whatever Beatles singles they could, resulting in huge hits that either went to #1 or charted very high, such as “Love Me Do” (#1), “Twist And Shout” (#2), “Please Please Me” (#3), “She Love You” (#1), “My Bonnie” (#26), “Ain't She Sweet” (#19) and “Do You Want To Know A Secret” (#2). In 1964 when The Beatles broke onto the scene in America, they seemed to be able to do no wrong as far as hit singles were concerned. “I Want To Hold Your Hand” raced up to the #1 spot on the US Billboard Hot 100, staying there for an amazing seven weeks. From that point on, nearly every new official Beatles release reached the top spot on this chart, as did some unofficial singles such as “Eight Days A Week” and “Yesterday.” Any record label that had license to do so released whatever Beatles singles they could, resulting in huge hits that either went to #1 or charted very high, such as “Love Me Do” (#1), “Twist And Shout” (#2), “Please Please Me” (#3), “She Love You” (#1), “My Bonnie” (#26), “Ain't She Sweet” (#19) and “Do You Want To Know A Secret” (#2).

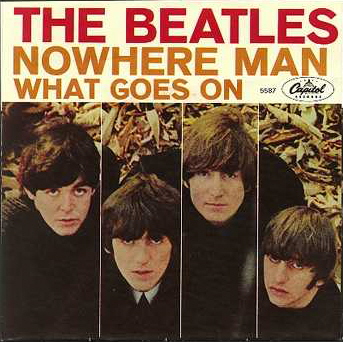

Beatles b-sides also inundated the airwaves and charts, resulting in songs like “P.S. I Love You” (#10), “I Saw Her Standing There” (#14), “Thank You Girl” (#35), “She's A Woman” (#4) and “I Don't Want To Spoil The Party” (#39) becoming hits, to mention only a few. Even Capitol Records, who were granted distributorship in America, were caught releasing additional Beatles singles to capitalize on their fame, “And I Love Her” (#12), “I'll Cry Instead” (#25), “Matchbox” (#17) and “Nowhere Man” (#3) among the many that resulted in huge revenues for both the group and the label. Beatles b-sides also inundated the airwaves and charts, resulting in songs like “P.S. I Love You” (#10), “I Saw Her Standing There” (#14), “Thank You Girl” (#35), “She's A Woman” (#4) and “I Don't Want To Spoil The Party” (#39) becoming hits, to mention only a few. Even Capitol Records, who were granted distributorship in America, were caught releasing additional Beatles singles to capitalize on their fame, “And I Love Her” (#12), “I'll Cry Instead” (#25), “Matchbox” (#17) and “Nowhere Man” (#3) among the many that resulted in huge revenues for both the group and the label.

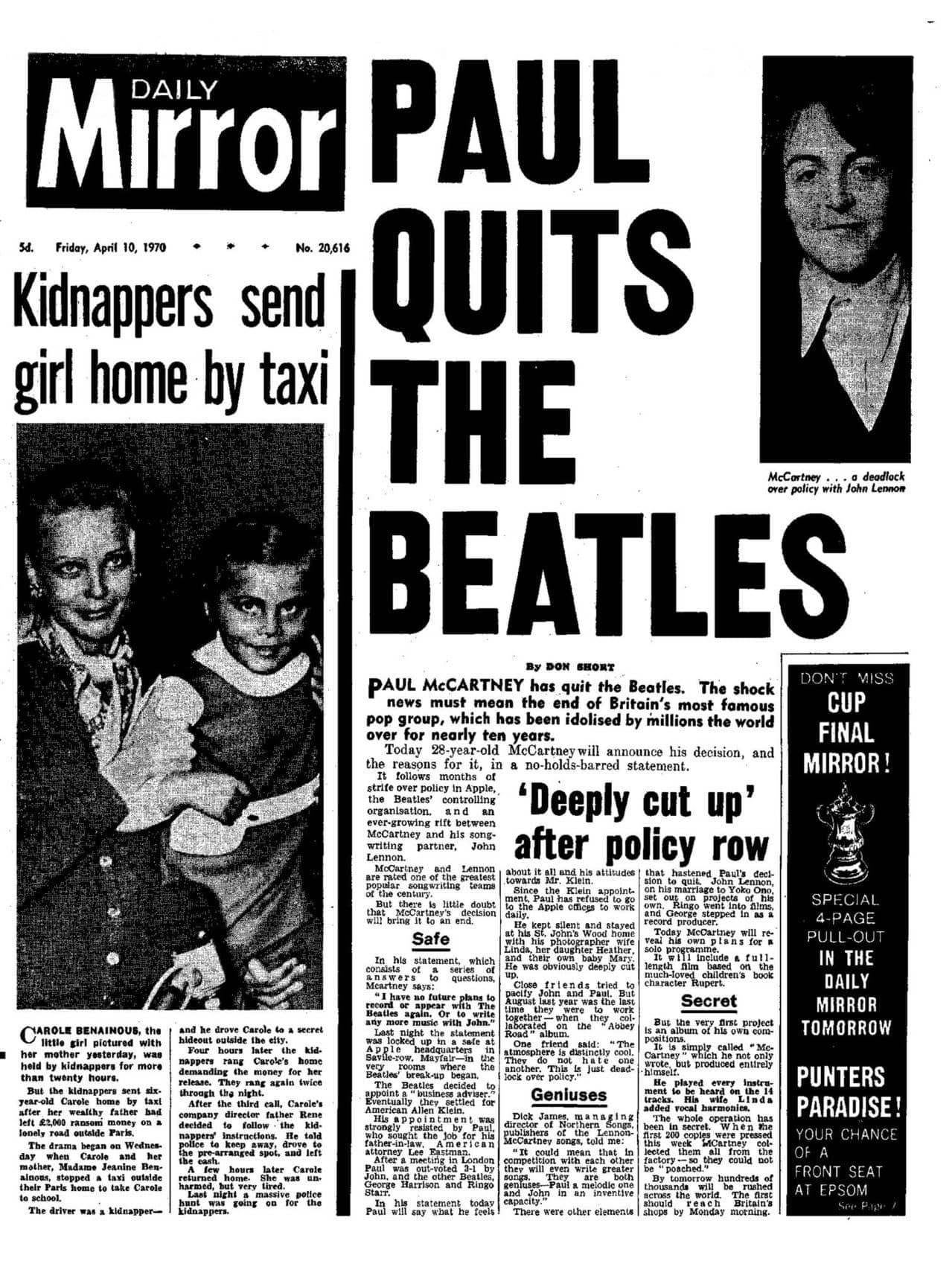

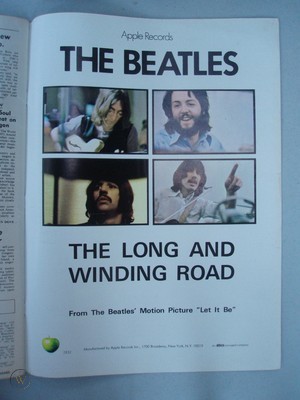

All in all, The Beatles reached the #1 spot on the Billboard Hot 100 a total of twenty times. Even after it was officially anounced in April of 1970 that the group had split up, they still reached the top spot on the pop chart with their final American single “The Long And Winding Road,” which was released the following month. Although unintentional, the lyrical message of this song appeared to sum up their successful career, at least in the minds of their legion of fans around the world. All in all, The Beatles reached the #1 spot on the Billboard Hot 100 a total of twenty times. Even after it was officially anounced in April of 1970 that the group had split up, they still reached the top spot on the pop chart with their final American single “The Long And Winding Road,” which was released the following month. Although unintentional, the lyrical message of this song appeared to sum up their successful career, at least in the minds of their legion of fans around the world.

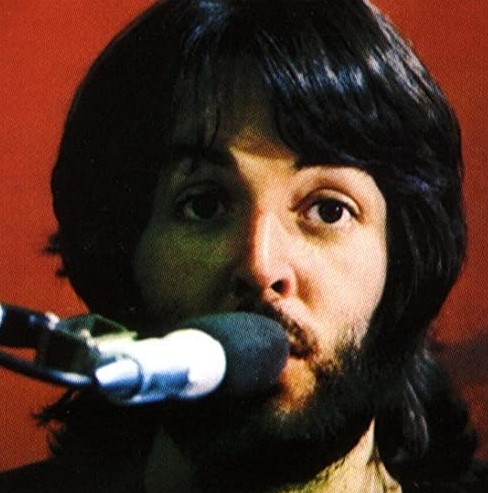

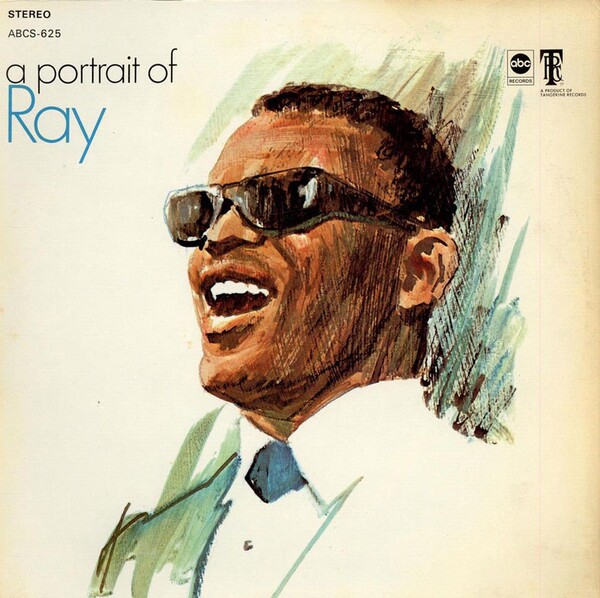

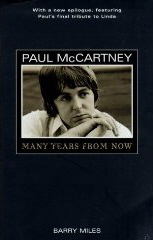

Songwriting History

At some point during the making of the “White Album,” estimated at September of 1968, Paul set out to write a song in the style of Ray Charles. “It doesn't sound like him at all,” Paul explains in his book “Many Years From Now,” “because it's me singing and I don't sound anything like Ray, but sometimes you get a person in your mind, just for an attitude, just for a place to be, so that your mind is somewhere rather than nowhere, and you place it by thinking, 'Oh, I love that Ray Charles,' and think, 'Well, what might he do then?' So that was in my mind, and would have probably had some bearing on the chord structure of it, which is slightly jazzy. I think I could attribute that to having Ray in my mind when I wrote that one.” At some point during the making of the “White Album,” estimated at September of 1968, Paul set out to write a song in the style of Ray Charles. “It doesn't sound like him at all,” Paul explains in his book “Many Years From Now,” “because it's me singing and I don't sound anything like Ray, but sometimes you get a person in your mind, just for an attitude, just for a place to be, so that your mind is somewhere rather than nowhere, and you place it by thinking, 'Oh, I love that Ray Charles,' and think, 'Well, what might he do then?' So that was in my mind, and would have probably had some bearing on the chord structure of it, which is slightly jazzy. I think I could attribute that to having Ray in my mind when I wrote that one.”

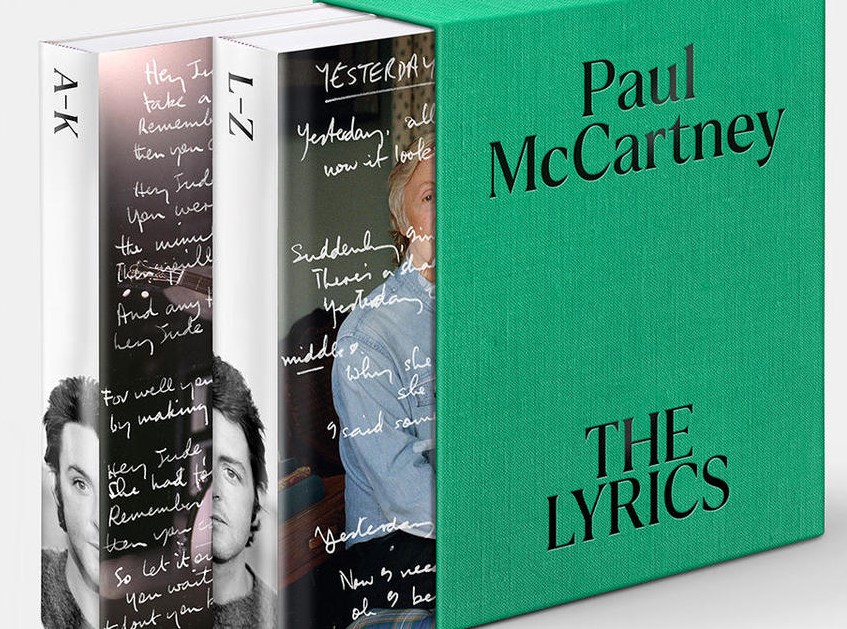

In his 2021 book "The Lyrics," Paul adds, "Often when I write a song, I do a bit of a disappearing trick myself. For example, I imagine it had been recorded by somebody else, in this case by Ray Charles. As usual, the last thing I'd want to be writing is a Paul McCartney song. This is a stategy for keeping things fresh...There's always someone else you can invoke. You can put on a mask and a cloak as you're writing something, and it takes away a lot of the anxiety. It frees you up. You discover as you get through it that it wasn't a Ray Charles song anyway; it way yours. The song take on its own character." Interestingly, Ray Charles did record the song as included on his April 1971 released album “Volcanic Action Of My Soul.” In his 2021 book "The Lyrics," Paul adds, "Often when I write a song, I do a bit of a disappearing trick myself. For example, I imagine it had been recorded by somebody else, in this case by Ray Charles. As usual, the last thing I'd want to be writing is a Paul McCartney song. This is a stategy for keeping things fresh...There's always someone else you can invoke. You can put on a mask and a cloak as you're writing something, and it takes away a lot of the anxiety. It frees you up. You discover as you get through it that it wasn't a Ray Charles song anyway; it way yours. The song take on its own character." Interestingly, Ray Charles did record the song as included on his April 1971 released album “Volcanic Action Of My Soul.”

As for the lyrical content, Paul continues: “It's a rather sad song. I like writing sad songs, it's a good bag to get into because you can actually acknowledge some deeper feelings of your own and put them in it. It's a good vehicle, it saves having to go to a psychiatrist. Songwriting often performs that feat, you say it but you don't embarrass yourself because it's only a song, or is it? You are putting the things that are bothering you on the table and you are reviewing them, but because it's a song, you don't have to argue with anyone. I was a bit flipped out and tripped out at that time. It's a sad song because it's all about the unattainable; the door you never quite reach. This is the road that you never get to the end of." In his book "The Lyrics," Paul adds, "One of the fascinating aspects of this song is that it seems to resonate in very powerful ways. For those who were there at the time, there seems to be a double association of terrific sadness and also a sense of hope, particulary in the assertion that the road that 'leads to your door / will never disappear.'...The road leads not to (the main Scotland town of) Campbeltown, but to somewhere you never expected." As for the lyrical content, Paul continues: “It's a rather sad song. I like writing sad songs, it's a good bag to get into because you can actually acknowledge some deeper feelings of your own and put them in it. It's a good vehicle, it saves having to go to a psychiatrist. Songwriting often performs that feat, you say it but you don't embarrass yourself because it's only a song, or is it? You are putting the things that are bothering you on the table and you are reviewing them, but because it's a song, you don't have to argue with anyone. I was a bit flipped out and tripped out at that time. It's a sad song because it's all about the unattainable; the door you never quite reach. This is the road that you never get to the end of." In his book "The Lyrics," Paul adds, "One of the fascinating aspects of this song is that it seems to resonate in very powerful ways. For those who were there at the time, there seems to be a double association of terrific sadness and also a sense of hope, particulary in the assertion that the road that 'leads to your door / will never disappear.'...The road leads not to (the main Scotland town of) Campbeltown, but to somewhere you never expected."

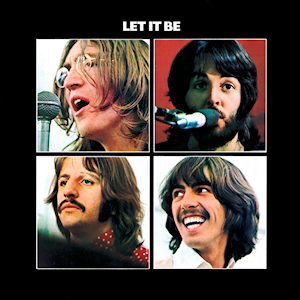

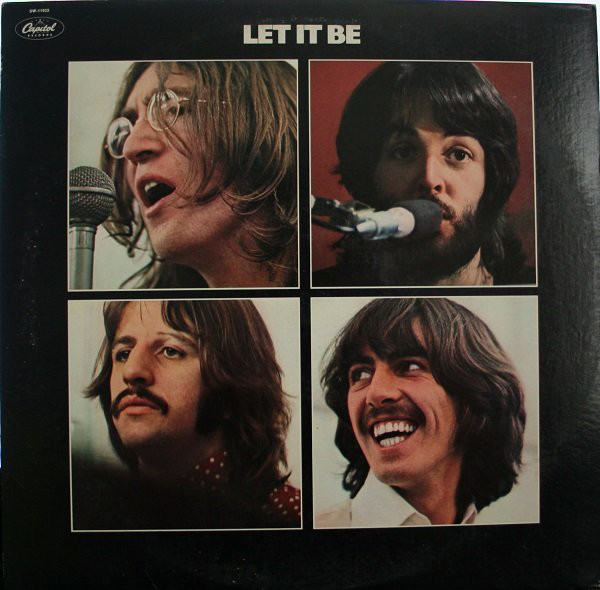

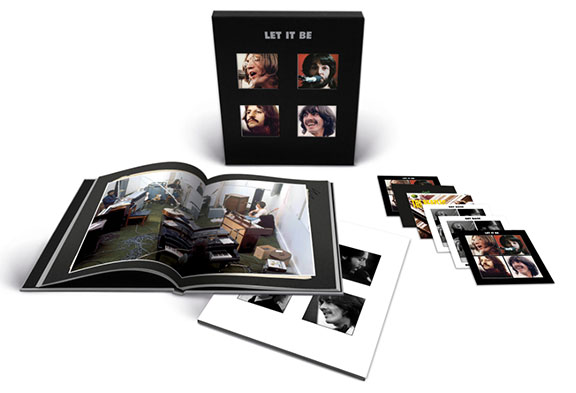

In the book contained in the 2021 "Super Deluxe" edition of the "Let It Be" album, Paul elaborated further. "A lot of songs, particularly at that time, were about your personal feelings. What I tend to do in a song is to put in some kind of analogy, like a 'long and winding road.' I don't say, 'I've been a long time getting here.' I'll say, 'A long and winding road led me here.' That's just an artistic device that anyone writing a song or novel or play would use. I was not particularly trying to put my own feelings into it, but that is often what happens: 'Don't leave me standing here.' You find these lines arrive and it's to do with your personal situation at the time. You don't always realize it." It can be surmised that, subliminally at least, Paul may very well have been here writing about his frustration concerning the future of The Beatles and the anguish concerning the direction of his personal life at the time, John being the person who left him "standing here" as the band was slowly disintegrating. In the book contained in the 2021 "Super Deluxe" edition of the "Let It Be" album, Paul elaborated further. "A lot of songs, particularly at that time, were about your personal feelings. What I tend to do in a song is to put in some kind of analogy, like a 'long and winding road.' I don't say, 'I've been a long time getting here.' I'll say, 'A long and winding road led me here.' That's just an artistic device that anyone writing a song or novel or play would use. I was not particularly trying to put my own feelings into it, but that is often what happens: 'Don't leave me standing here.' You find these lines arrive and it's to do with your personal situation at the time. You don't always realize it." It can be surmised that, subliminally at least, Paul may very well have been here writing about his frustration concerning the future of The Beatles and the anguish concerning the direction of his personal life at the time, John being the person who left him "standing here" as the band was slowly disintegrating.

As for the visual depictions of wind, rain, and the road itself, Steve Turner's book “A Hard Day's Write” suggests the B842, a 16-mile stretch of road that twists and turns down the east coast of Kintyre into Campbeltown near Paul's High Park farm in Scotland. This undoubtedly is the road that Paul referred to as “stretching up into the hills” in a 2010 interview with Howard Sounes for the book “Fab: An Intimate Life With Paul McCartney.” Paul purchased this 200-acre property with farm house on June 17th, 1966 as an investment and as a retreat to escape Beatlemania. It was “exposed to high winds and frequently lashed with rain,” according to author Steve Turner, which is assumed to have contributed to the song's imagery. As for the visual depictions of wind, rain, and the road itself, Steve Turner's book “A Hard Day's Write” suggests the B842, a 16-mile stretch of road that twists and turns down the east coast of Kintyre into Campbeltown near Paul's High Park farm in Scotland. This undoubtedly is the road that Paul referred to as “stretching up into the hills” in a 2010 interview with Howard Sounes for the book “Fab: An Intimate Life With Paul McCartney.” Paul purchased this 200-acre property with farm house on June 17th, 1966 as an investment and as a retreat to escape Beatlemania. It was “exposed to high winds and frequently lashed with rain,” according to author Steve Turner, which is assumed to have contributed to the song's imagery.

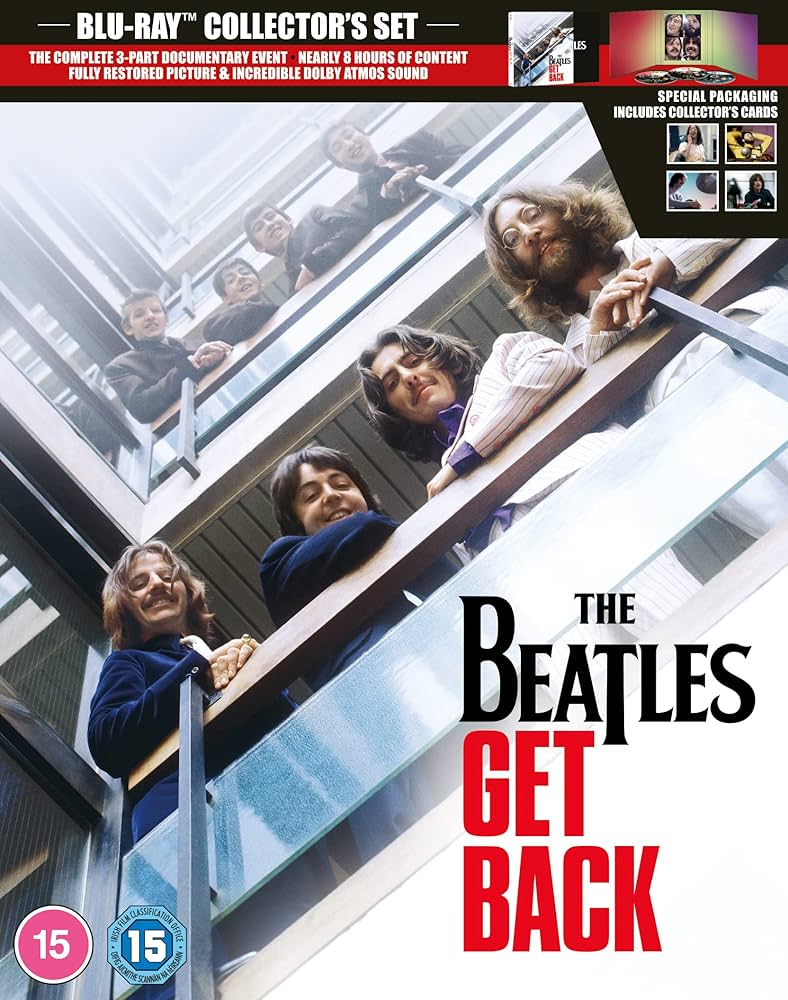

"From the bedroom window of my farmhouse on the Mull of Kintyre, in Argyllshire, I could see a road that twisted away into the distance towards the main road," Paul related in his book "The Lyrics." "That's how you got into town, Campbeltown, to be precise. I'd bought High Park Farm back in 1966. It was a very remote retreat, and the farmhouse was virtually derelict and probably would've stayed that way if Linda hadn't said we should do the place up. It wasn't until two years later that the image of this distant, winding road would become fully developed as a song." Since the song was still being formulated in January of 1969, as evidenced in the Peter Jackson documentary "Get Back" with Beatles assistant Mal Evans, the song wasn't "fully developed" until then. "From the bedroom window of my farmhouse on the Mull of Kintyre, in Argyllshire, I could see a road that twisted away into the distance towards the main road," Paul related in his book "The Lyrics." "That's how you got into town, Campbeltown, to be precise. I'd bought High Park Farm back in 1966. It was a very remote retreat, and the farmhouse was virtually derelict and probably would've stayed that way if Linda hadn't said we should do the place up. It wasn't until two years later that the image of this distant, winding road would become fully developed as a song." Since the song was still being formulated in January of 1969, as evidenced in the Peter Jackson documentary "Get Back" with Beatles assistant Mal Evans, the song wasn't "fully developed" until then.

It was here at this farm in Scotland where Paul began composing the song. “I just sat down at my piano in Scotland,” McCartney related to journalist Mike Merritt in 2003, “started playing and came up with that song, imagining it would be done by someone like Ray Charles. I have always found inspiration in the calm beauty of Scotland and again it proved the place where I found inspiration.” It was here at this farm in Scotland where Paul began composing the song. “I just sat down at my piano in Scotland,” McCartney related to journalist Mike Merritt in 2003, “started playing and came up with that song, imagining it would be done by someone like Ray Charles. I have always found inspiration in the calm beauty of Scotland and again it proved the place where I found inspiration.”

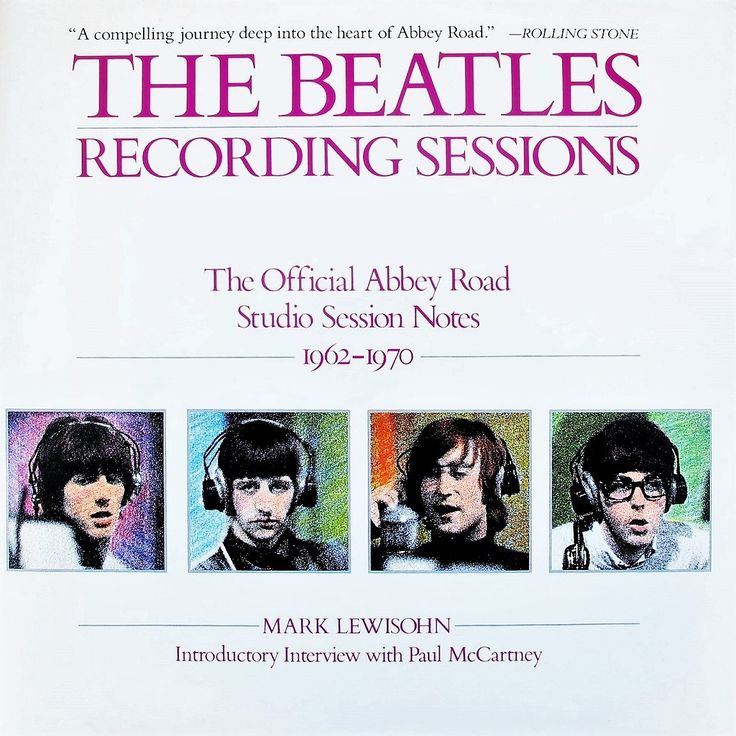

The song is estimated to have begun being written in September of 1968 due to a recollection of engineer Alan Brown. Although the precise date is unknown, Alan Brown remembers “assisting Paul McCartney to quickly tape a demo version of 'The Long And Winding Road' at the grand piano in (EMI) Studio One, and then handing over the spool of tape to Paul,” as detailed in Mark Lewisohn's book “The Beatles Recording Sessions.” The book cites this account as possibly occuring on September 19th, 1968, during the late night sessions for the song “Piggies” in both EMI Studios One and Two. The song is estimated to have begun being written in September of 1968 due to a recollection of engineer Alan Brown. Although the precise date is unknown, Alan Brown remembers “assisting Paul McCartney to quickly tape a demo version of 'The Long And Winding Road' at the grand piano in (EMI) Studio One, and then handing over the spool of tape to Paul,” as detailed in Mark Lewisohn's book “The Beatles Recording Sessions.” The book cites this account as possibly occuring on September 19th, 1968, during the late night sessions for the song “Piggies” in both EMI Studios One and Two.

Adding credibility to this recollection is the account of Apple office manager Alistair Taylor, nicknamed “Mr. Fixit” by the group, as recounted in George Gunby's book “Hello Goodbye: The Story Of 'Mr. Fixit.'” The details that follow, as found in George Gunby's book, could easily be attributed to the early Friday morning events of September 19th, 1968 (or thereabouts) in EMI Studio One, as engineer Alan Brown detailed above. Adding credibility to this recollection is the account of Apple office manager Alistair Taylor, nicknamed “Mr. Fixit” by the group, as recounted in George Gunby's book “Hello Goodbye: The Story Of 'Mr. Fixit.'” The details that follow, as found in George Gunby's book, could easily be attributed to the early Friday morning events of September 19th, 1968 (or thereabouts) in EMI Studio One, as engineer Alan Brown detailed above.

“The finest example of Paul's songwriting turned out just as Alistair (Taylor) had hoped. It was the end of a particularly difficult week at (EMI Studios) and Apple during which he had been working twenty-hour days. He was feeling the effects of being, virtually, Paul's personal assistant and keeping an eye on things at the office. He was very, very tired and looking forward to spending Saturday and Sunday at home with (his wife) Lesley (Taylor). As the Friday night session wound down he went in search of Paul to say goodnight. John, George and Ringo had no idea where McCartney was and when he could not be found in the canteen or any of the offices Alistair (Taylor) pretty much gave up.” “The finest example of Paul's songwriting turned out just as Alistair (Taylor) had hoped. It was the end of a particularly difficult week at (EMI Studios) and Apple during which he had been working twenty-hour days. He was feeling the effects of being, virtually, Paul's personal assistant and keeping an eye on things at the office. He was very, very tired and looking forward to spending Saturday and Sunday at home with (his wife) Lesley (Taylor). As the Friday night session wound down he went in search of Paul to say goodnight. John, George and Ringo had no idea where McCartney was and when he could not be found in the canteen or any of the offices Alistair (Taylor) pretty much gave up.”

“As he passed the cavernous Studio One he noticed a feint light. Stepping quietly inside, he stood in the shadows and listened as the figure hunched over the grand piano picked out a melody and began adding lyrics. The voice was unmistakably McCartney's. Alistair (Taylor) listened intently as the tune developed. More lyrics were added. 'This is sensational,' Alistair (Taylor) thought. Spellbound, he walked over to the piano when Paul stopped playing. 'That is a beautiful, beautiful melody and fabulous words,' he said. 'Lesley (Taylor) would love that.' Paul smiled. 'It's just an idea at this stage,' he said. 'For “just an idea” it's sensational.'” “As he passed the cavernous Studio One he noticed a feint light. Stepping quietly inside, he stood in the shadows and listened as the figure hunched over the grand piano picked out a melody and began adding lyrics. The voice was unmistakably McCartney's. Alistair (Taylor) listened intently as the tune developed. More lyrics were added. 'This is sensational,' Alistair (Taylor) thought. Spellbound, he walked over to the piano when Paul stopped playing. 'That is a beautiful, beautiful melody and fabulous words,' he said. 'Lesley (Taylor) would love that.' Paul smiled. 'It's just an idea at this stage,' he said. 'For “just an idea” it's sensational.'”

"Paul looked up to the control room. 'Have you got any tape left?' he asked the engineer who nodded. 'Roll it, please,' McCartney said. Alistair (Taylor) stood by the piano as Paul ran through the song again. Although not the finished article, the fundamental outline and character were clear and distinct. It was, Alistair (Taylor) felt, destined to be a classic. When the song ended he applauded quietly. Paul looked up from the keyboard. 'Glad you like it,' he said. 'Now go home. You look shattered.'” "Paul looked up to the control room. 'Have you got any tape left?' he asked the engineer who nodded. 'Roll it, please,' McCartney said. Alistair (Taylor) stood by the piano as Paul ran through the song again. Although not the finished article, the fundamental outline and character were clear and distinct. It was, Alistair (Taylor) felt, destined to be a classic. When the song ended he applauded quietly. Paul looked up from the keyboard. 'Glad you like it,' he said. 'Now go home. You look shattered.'”

“Monday morning came round far too quickly for Alistair (Taylor). He was in the office early and had cleared most things by the time Paul appeared in mid afternoon. He sat down and asked how Lesley (Taylor) was. 'Fine,' Alistair (Taylor) replied. 'Did you tell her about the song?' 'No. I couldn't do it justice.' 'Well you can now,' McCartney said with a broad grin. From inside his coat he pulled out an acetate record and placed it on the desk in front of Alistair (Taylor). 'That's the recording from Friday...It's for Lesley (Taylor).' 'You shouldn't have. Thank you very much.' 'Give me your waste bin and a pair of scissors,' Paul said. As Alistair (Taylor) handed them to him, McCartney pulled a spool of recording tape from his pocket. 'That's the tape from Friday,' he said as he picked up the scissors and proceeded to cut it into small pieces that fell into the waste bin.” “Monday morning came round far too quickly for Alistair (Taylor). He was in the office early and had cleared most things by the time Paul appeared in mid afternoon. He sat down and asked how Lesley (Taylor) was. 'Fine,' Alistair (Taylor) replied. 'Did you tell her about the song?' 'No. I couldn't do it justice.' 'Well you can now,' McCartney said with a broad grin. From inside his coat he pulled out an acetate record and placed it on the desk in front of Alistair (Taylor). 'That's the recording from Friday...It's for Lesley (Taylor).' 'You shouldn't have. Thank you very much.' 'Give me your waste bin and a pair of scissors,' Paul said. As Alistair (Taylor) handed them to him, McCartney pulled a spool of recording tape from his pocket. 'That's the tape from Friday,' he said as he picked up the scissors and proceeded to cut it into small pieces that fell into the waste bin.”

“'Now you have the only copy of that recording in the world,' he said with a broad smile. 'Thank you very much,' Alistair (Taylor) said. 'It's my way of saying “thank you,”' Paul said as he stood to leave the office. 'Just one thing, what's it called?' '”The Long And Winding Road,”' McCartney replied.” “'Now you have the only copy of that recording in the world,' he said with a broad smile. 'Thank you very much,' Alistair (Taylor) said. 'It's my way of saying “thank you,”' Paul said as he stood to leave the office. 'Just one thing, what's it called?' '”The Long And Winding Road,”' McCartney replied.”

Since the song was not lyrically finished at the time, Paul didn't push to record it for inclusion on the “White Album.” Instead, he held it over for the next project, this being what became the “Let It Be” film and soundtrack album that began being reheared in early January of 1969. These filmed rehearsals reveal that Paul went over the song on piano a number of times at Twickenham Film Studios in the first few days. While the chords and melody of the song were in place at this time, the only lyrics written were of one verse and a partial bridge. Since the song was not lyrically finished at the time, Paul didn't push to record it for inclusion on the “White Album.” Instead, he held it over for the next project, this being what became the “Let It Be” film and soundtrack album that began being reheared in early January of 1969. These filmed rehearsals reveal that Paul went over the song on piano a number of times at Twickenham Film Studios in the first few days. While the chords and melody of the song were in place at this time, the only lyrics written were of one verse and a partial bridge.

Paul gets a little further with the lyrics on January 9th, 1969, as seen in Peter Jackson's 2021 "Get Back" documentary series. Paul sits down at the piano to go over some songs while waiting for George and John to arrive. When assistant Mal Evans asks "Do you have any more words to write out? More songs?," Paul starts dictating to him what he has so far for "The Long And Winding Road." After the first verse, Paul sings "The second verse that I haven't got yet - leave a space for the same thing, la, la, la." Mal Evans then equates the lyrics of the first verse with a famous movie. "Did you ever see the Wizard Of Oz?" he asks, to which Paul replies, "No, No, No I didn't," this prompting Mal Evans to mention "the yellow brick road." For the bridge, Paul tries to incorporate the word "pleasure," such as "all the pleasure from the many ways I've tried," but then states his idea as "'I've had lots of pleasure' but said better, y'know, 'I've had many pleasure ever, much, much.'" When moving into the third verse, Paul sings "You left me waiting here," to which Mal Evans states, "Use 'standing.'" "You like 'standing' better?," Paul asks, to which Mal Evans responds, "Yeah, put 'waiting' there and 'standing' here." After Paul demonstrates this, he tells Mal Evans, "There's no more to that yet. Just call that 'middle.'" Paul gets a little further with the lyrics on January 9th, 1969, as seen in Peter Jackson's 2021 "Get Back" documentary series. Paul sits down at the piano to go over some songs while waiting for George and John to arrive. When assistant Mal Evans asks "Do you have any more words to write out? More songs?," Paul starts dictating to him what he has so far for "The Long And Winding Road." After the first verse, Paul sings "The second verse that I haven't got yet - leave a space for the same thing, la, la, la." Mal Evans then equates the lyrics of the first verse with a famous movie. "Did you ever see the Wizard Of Oz?" he asks, to which Paul replies, "No, No, No I didn't," this prompting Mal Evans to mention "the yellow brick road." For the bridge, Paul tries to incorporate the word "pleasure," such as "all the pleasure from the many ways I've tried," but then states his idea as "'I've had lots of pleasure' but said better, y'know, 'I've had many pleasure ever, much, much.'" When moving into the third verse, Paul sings "You left me waiting here," to which Mal Evans states, "Use 'standing.'" "You like 'standing' better?," Paul asks, to which Mal Evans responds, "Yeah, put 'waiting' there and 'standing' here." After Paul demonstrates this, he tells Mal Evans, "There's no more to that yet. Just call that 'middle.'"

When Mal Evans asks if he as "any ideas for the second verse," Paul replies, "I was thinking of having, like another, like the weather obstacle," and then sings, "The storm clouds la, la, rain break apart while you roam." Mal Evans suggests, "The black and stormy rainclouds which gather 'round your door," which prompts Paul to smile and say, "I suppose it should still be about the sort of winding road. I've just got that picture. It'll be like that thing that's up ahead." Paul then humorously sings, "The thing that's up ahead." Mal Evans then suggests, "Like, what about the obstacles on the road?," to which Paul replies, "No, I think, y'know, there's enough obstacles without putting them in the song." When Mal Evans asks if he as "any ideas for the second verse," Paul replies, "I was thinking of having, like another, like the weather obstacle," and then sings, "The storm clouds la, la, rain break apart while you roam." Mal Evans suggests, "The black and stormy rainclouds which gather 'round your door," which prompts Paul to smile and say, "I suppose it should still be about the sort of winding road. I've just got that picture. It'll be like that thing that's up ahead." Paul then humorously sings, "The thing that's up ahead." Mal Evans then suggests, "Like, what about the obstacles on the road?," to which Paul replies, "No, I think, y'know, there's enough obstacles without putting them in the song."

When Paul eventually began to teach the song to his band-mates in earnest on January 26th, 1969 at their Apple basement studio, 3 Saville Row, London, the lyrics were complete. Therefore, it can confidently be said that “The Long And Winding Road” was written between September 1968 and January 26th, 1969. When Paul eventually began to teach the song to his band-mates in earnest on January 26th, 1969 at their Apple basement studio, 3 Saville Row, London, the lyrics were complete. Therefore, it can confidently be said that “The Long And Winding Road” was written between September 1968 and January 26th, 1969.

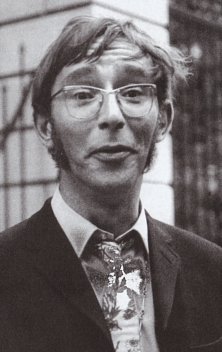

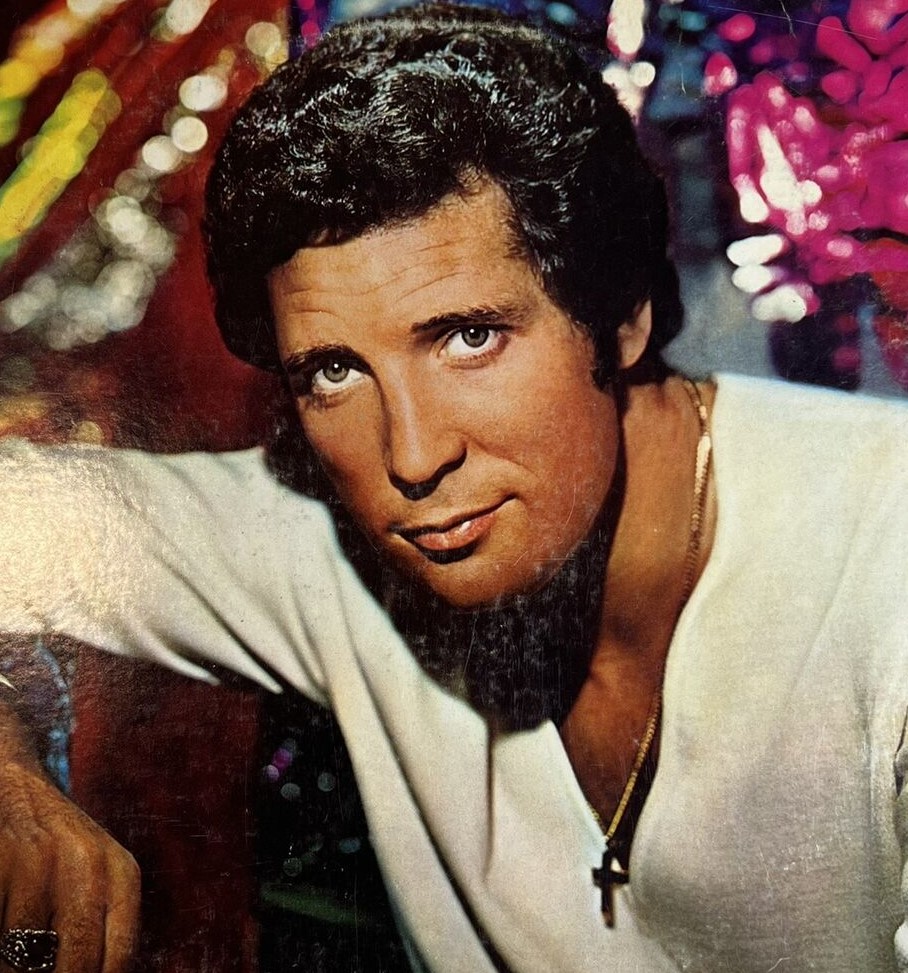

There appears to be someone other than Ray Charles that McCartney had in mind to record the song. “I saw him in a club called 'Scotch Of St. James' on Jeremy Street in London,” recalled singer Tom Jones in 2012 about a chance meeting with Paul in the fall of 1969. “So I said to him, 'When are you going to write me a song then, Paul?' He said, 'Aye, I will then.' Then not long after, he sent a song around to my house, which was 'The Long And Winding Road,' but the condition was that I could do it but it had to be my next single.” The Beatles had already officially recorded “The Long And Winding Road” months earlier but, since the fate of the “Let It Be” project was up in the air at this point, Paul apparently didn't want to waste a good song. There appears to be someone other than Ray Charles that McCartney had in mind to record the song. “I saw him in a club called 'Scotch Of St. James' on Jeremy Street in London,” recalled singer Tom Jones in 2012 about a chance meeting with Paul in the fall of 1969. “So I said to him, 'When are you going to write me a song then, Paul?' He said, 'Aye, I will then.' Then not long after, he sent a song around to my house, which was 'The Long And Winding Road,' but the condition was that I could do it but it had to be my next single.” The Beatles had already officially recorded “The Long And Winding Road” months earlier but, since the fate of the “Let It Be” project was up in the air at this point, Paul apparently didn't want to waste a good song.

“Paul wanted it out straight away," Tom Jones continued. "At that time I had a song called 'Without Love' that I was going to be releasing...I asked if we could stop everything and I could do 'The Long And Winding Road.' They said it would take a lot of time and it was impractical, so I ended up not doing it.” “Without Love” ended up becoming a million-selling #5 hit single for Tom Jones in the early months of 1970, so it was no loss for the British crooner to pass on releasing the McCartney ballad after all. “Paul wanted it out straight away," Tom Jones continued. "At that time I had a song called 'Without Love' that I was going to be releasing...I asked if we could stop everything and I could do 'The Long And Winding Road.' They said it would take a lot of time and it was impractical, so I ended up not doing it.” “Without Love” ended up becoming a million-selling #5 hit single for Tom Jones in the early months of 1970, so it was no loss for the British crooner to pass on releasing the McCartney ballad after all.

As to any collaboration from John on this “Lennon / McCartney” composition, it appears to be nonexistent. When asked about the song during his 1980 Playboy Magazine interview, John replied: "That's Paul. He had a little spurt before we finally split up. I think the shock of what was happening between Yoko and me gave him the creative spurt for 'Let It Be' and 'The Long And Winding Road.' That was the last gasp from him." As to any collaboration from John on this “Lennon / McCartney” composition, it appears to be nonexistent. When asked about the song during his 1980 Playboy Magazine interview, John replied: "That's Paul. He had a little spurt before we finally split up. I think the shock of what was happening between Yoko and me gave him the creative spurt for 'Let It Be' and 'The Long And Winding Road.' That was the last gasp from him."

"Given the popularity of The Beatles, a lot of our phrases have themselves crept into everyday language," Paul explains in the 2023 edition of his book "The Lyrics." "That happens a lot with journalists, they will quote, 'Well, it's been a long, winding road to get here.' You see things like 'let it be,' 'all you need is love,' 'we can work it out' quite a bit. They're just throwing these titles in because they work so well as a phrase. And there's that little allusion to The Beatles' song. I am always very pleased to see all those. because I think, 'Oh, they've got that from us.'" "Given the popularity of The Beatles, a lot of our phrases have themselves crept into everyday language," Paul explains in the 2023 edition of his book "The Lyrics." "That happens a lot with journalists, they will quote, 'Well, it's been a long, winding road to get here.' You see things like 'let it be,' 'all you need is love,' 'we can work it out' quite a bit. They're just throwing these titles in because they work so well as a phrase. And there's that little allusion to The Beatles' song. I am always very pleased to see all those. because I think, 'Oh, they've got that from us.'"

Recording History

As detailed above, Paul set his as yet unfinished “The Long And Winding Road” to tape for the first time in EMI Studio One on September 19th, 1968 (or thereabouts). Towards the conclusion of the recording session on that day, Paul sat at the grand piano and asked engineer Alan Brown to record this demo, the tape being given directly to the composer afterward. McCartney thereby made an acetate disc of the song, gave it to his assistant Alistair Taylor as a gift for his wife Lesley, and destroyed the demo tape in front of him. Since the passing of Alistair Taylor in 2004, no one appears to know the whereabouts of this acetate, the only evidence of McCartney's demo of “The Long And Winding Road.” As detailed above, Paul set his as yet unfinished “The Long And Winding Road” to tape for the first time in EMI Studio One on September 19th, 1968 (or thereabouts). Towards the conclusion of the recording session on that day, Paul sat at the grand piano and asked engineer Alan Brown to record this demo, the tape being given directly to the composer afterward. McCartney thereby made an acetate disc of the song, gave it to his assistant Alistair Taylor as a gift for his wife Lesley, and destroyed the demo tape in front of him. Since the passing of Alistair Taylor in 2004, no one appears to know the whereabouts of this acetate, the only evidence of McCartney's demo of “The Long And Winding Road.”

The next time that Paul presented the song in the studio was on January 3rd, 1969, the second day of rehearsals at Twickenham Film Studios for what eventually became the “Let It Be” film and soundtrack album. Paul was the first to arrive on this day, Ringo and George showing up shortly thereafter. Since John was late, the three of them premiered some song ideas for consideration for the project. Paul played a brief segment of “The Long And Winding Road,” as well as “Let It Be” and others, while Ringo demonstrated his ideas for “Taking A Trip To Carolina” and “Picasso” and George played them “It Is Discovered” and a Dylanesque song entitled “Ramblin' Woman.” After John finally arrived, they dived deep into group arrangements such as “I've Got A Feeling” and “One After 909.” The next time that Paul presented the song in the studio was on January 3rd, 1969, the second day of rehearsals at Twickenham Film Studios for what eventually became the “Let It Be” film and soundtrack album. Paul was the first to arrive on this day, Ringo and George showing up shortly thereafter. Since John was late, the three of them premiered some song ideas for consideration for the project. Paul played a brief segment of “The Long And Winding Road,” as well as “Let It Be” and others, while Ringo demonstrated his ideas for “Taking A Trip To Carolina” and “Picasso” and George played them “It Is Discovered” and a Dylanesque song entitled “Ramblin' Woman.” After John finally arrived, they dived deep into group arrangements such as “I've Got A Feeling” and “One After 909.”

Then on January 7th, 1969, Paul once again put some effort into working out the bugs of “The Long And Winding Road” on piano before the others arrived at Twickenham, this time running through it for nearly five minutes. Most of the piano work was solidified at this point, but the lyrics only amounted to the first verse and the line “Many times I've been alone / and many times I've cried” in the bridge. After Ringo and George arrived, he played a bit of the song for them but that's as far as it went. Paul also touched on the song by himself once more later in the day in between rehearsals of other compositions. Then on January 7th, 1969, Paul once again put some effort into working out the bugs of “The Long And Winding Road” on piano before the others arrived at Twickenham, this time running through it for nearly five minutes. Most of the piano work was solidified at this point, but the lyrics only amounted to the first verse and the line “Many times I've been alone / and many times I've cried” in the bridge. After Ringo and George arrived, he played a bit of the song for them but that's as far as it went. Paul also touched on the song by himself once more later in the day in between rehearsals of other compositions.

The next day, January 8th, 1969, saw Paul take some time to acquaint his band-mates with the song at Twickenham. During their extensive rehearsals of George's “I Me Mine,” Paul decided to begin teaching John the chords to "The Long And Winding Road," which the guitarist showed some interest in learning. Later, when he tried to spark interest in the song with two more run-throughs, John declined to participate. The next day, January 8th, 1969, saw Paul take some time to acquaint his band-mates with the song at Twickenham. During their extensive rehearsals of George's “I Me Mine,” Paul decided to begin teaching John the chords to "The Long And Winding Road," which the guitarist showed some interest in learning. Later, when he tried to spark interest in the song with two more run-throughs, John declined to participate.

While waiting for George and John to arrive at Twickenham the following day, January 9th, 1969, Paul ran through the song five times on piano, dictating to Mal Evans what he had so far lyrically and writing a bit more for the bridge and third verse. (See "Songwriting History" for more details of this day.) Paul ran through the song by himself again the following day, January 10th, 1969, two piano rehearsals being performed while visiting Beatles publisher Dick James bends his ear. When lunch time arrives, George announces that he is quitting The Beatles, which dampens the mood considerably for the rest of the day, Paul doing one more instrumental rendition of "The Long And Winding Road" before the session was over. While it was clear that Paul had strong feelings about this composition, the entire Twickenham rehearsal sessions focused more on preparing the rock-and-roll tunes that would be featured at their upcoming live performance, whenever and wherever that may be. While waiting for George and John to arrive at Twickenham the following day, January 9th, 1969, Paul ran through the song five times on piano, dictating to Mal Evans what he had so far lyrically and writing a bit more for the bridge and third verse. (See "Songwriting History" for more details of this day.) Paul ran through the song by himself again the following day, January 10th, 1969, two piano rehearsals being performed while visiting Beatles publisher Dick James bends his ear. When lunch time arrives, George announces that he is quitting The Beatles, which dampens the mood considerably for the rest of the day, Paul doing one more instrumental rendition of "The Long And Winding Road" before the session was over. While it was clear that Paul had strong feelings about this composition, the entire Twickenham rehearsal sessions focused more on preparing the rock-and-roll tunes that would be featured at their upcoming live performance, whenever and wherever that may be.

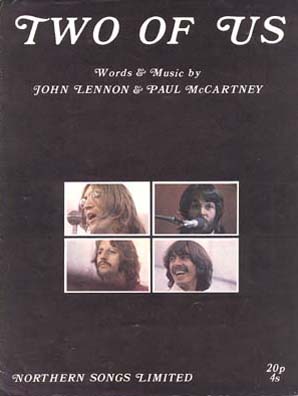

Once George had agreed to re-join The Beatles, they settled into their new basement recording studio at their Apple Headquarters on Savile Row in London for all future rehearsals. Their second session at this location was on January 22nd, 1969, which was the first day that keyboardist Billy Preston was present to add his talent into the mix. Paul ran through “The Long And Winding Road” three times on this day, although in just an instrumental form. He also squeezed in two more solo renditions of the song on the following day, January 23rd, 1969, although a serious attempt at working it out with the rest of the band was yet to come. Paul did run through it once briefly the following day at Apple Studios, January 24th, 1969, but their concentration at this session was primarily on perfecting the songs “Get Back” and “Two Of Us.” Once George had agreed to re-join The Beatles, they settled into their new basement recording studio at their Apple Headquarters on Savile Row in London for all future rehearsals. Their second session at this location was on January 22nd, 1969, which was the first day that keyboardist Billy Preston was present to add his talent into the mix. Paul ran through “The Long And Winding Road” three times on this day, although in just an instrumental form. He also squeezed in two more solo renditions of the song on the following day, January 23rd, 1969, although a serious attempt at working it out with the rest of the band was yet to come. Paul did run through it once briefly the following day at Apple Studios, January 24th, 1969, but their concentration at this session was primarily on perfecting the songs “Get Back” and “Two Of Us.”

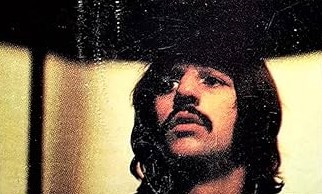

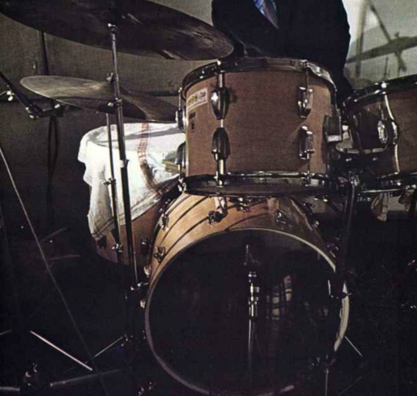

The day that The Beatles first seriously worked on “The Long And Winding Road” was January 26th, 1969, at Apple Studios. With the rock-and-roll songs pretty much perfected, Paul thought to focus on the ballads he had been working on, including the song “Let It Be.” With all of the lyrics as we know them finally in place, sixteen rehearsals of “The Long And Winding Road” took place on this day, all with Paul on piano, George on his Gibson J-200 acoustic guitar run through a Leslie speaker, John on Fender Bass VI, Ringo on drums and Billy Preston on electric piano. Over an hour of attention was given to this song at this session. It took some time for Paul to explain the syncopated beats he wanted in the second measure of each verse, Ringo and George habitually coming back in too early. "No, no, you've got to wait a lot longer than that," Paul instructs, "'cause if you syncopate it, it's like double syncopation." The day that The Beatles first seriously worked on “The Long And Winding Road” was January 26th, 1969, at Apple Studios. With the rock-and-roll songs pretty much perfected, Paul thought to focus on the ballads he had been working on, including the song “Let It Be.” With all of the lyrics as we know them finally in place, sixteen rehearsals of “The Long And Winding Road” took place on this day, all with Paul on piano, George on his Gibson J-200 acoustic guitar run through a Leslie speaker, John on Fender Bass VI, Ringo on drums and Billy Preston on electric piano. Over an hour of attention was given to this song at this session. It took some time for Paul to explain the syncopated beats he wanted in the second measure of each verse, Ringo and George habitually coming back in too early. "No, no, you've got to wait a lot longer than that," Paul instructs, "'cause if you syncopate it, it's like double syncopation."

Since they all were just getting acquainted with the chords and starting to work out an arrangement, many of these performances were quite dreadful. John in particular was having a hard time playing bass, which is not his usual instrument. Since their determination was to perform all of the songs in this project without overdubs and Paul was on piano on this occasion, John needed to play bass this time around. Paul even felt the need to call out chords and sing “bomm, bomm, bomm” at times to demonstrate vocally to John what he needed to play. John was not happy to learn that the song was in E flat major and that a capo wouldn't fit on the Fender VI bass he was using. "E flat? F*cking hell! All right. I'll just have to go hysterical," he joked. Since they all were just getting acquainted with the chords and starting to work out an arrangement, many of these performances were quite dreadful. John in particular was having a hard time playing bass, which is not his usual instrument. Since their determination was to perform all of the songs in this project without overdubs and Paul was on piano on this occasion, John needed to play bass this time around. Paul even felt the need to call out chords and sing “bomm, bomm, bomm” at times to demonstrate vocally to John what he needed to play. John was not happy to learn that the song was in E flat major and that a capo wouldn't fit on the Fender VI bass he was using. "E flat? F*cking hell! All right. I'll just have to go hysterical," he joked.

At one point, Paul had to instruct John not to play too many notes but only play on chord changes. Lennon did eventually fall upon the habit of pulling up the note on the neck of his bass in measures 6 and 8 of each verse as well as during the conclusion of the song, something he decided to stick with for the remainder of the month. In order to dispel some of the tension in learning the song, they delved into a cha-cha Latin-influenced version that lasted around one-and-a-half minutes, a portion of this being featured in the “Let It Be” movie and Peter Jackson's "Get Back" documentary series. Paul calls this to a halt with the words, “All right lads, that's enough! We could go on all bloody day!” At one point, Paul had to instruct John not to play too many notes but only play on chord changes. Lennon did eventually fall upon the habit of pulling up the note on the neck of his bass in measures 6 and 8 of each verse as well as during the conclusion of the song, something he decided to stick with for the remainder of the month. In order to dispel some of the tension in learning the song, they delved into a cha-cha Latin-influenced version that lasted around one-and-a-half minutes, a portion of this being featured in the “Let It Be” movie and Peter Jackson's "Get Back" documentary series. Paul calls this to a halt with the words, “All right lads, that's enough! We could go on all bloody day!”

After this, John begins to get the feel for the song on bass, although he appears to be mimicking Paul's vocal work. Paul, however, begins to get punchy, purposely goofing around on vocals by incorporating silly voices. After McCartney gives some instructions to Ringo on how he wants him to tinkle around on the cymbals during the verses, which we witness Ringo demonstrating in Peter Jackson's "Get Back" series, the drummer leans back at his drums and falls asleep as the others continue rehearsing the song. "There wouldn't be much drumming, would there?", Paul responds. The laid-back feel of the drum-less song prompts McCartney to state, "It sounds a bit like a, sort of, dance orchestra," and as the song continues, he announces, "...and that slow foxtrot by Rita and Thomas Williams!" John chimes in with, "Peter is wearing a dark sombrero and a beard," to which Paul adds, "the husband is wearing a crimling skirt which he made himself!" After this, John begins to get the feel for the song on bass, although he appears to be mimicking Paul's vocal work. Paul, however, begins to get punchy, purposely goofing around on vocals by incorporating silly voices. After McCartney gives some instructions to Ringo on how he wants him to tinkle around on the cymbals during the verses, which we witness Ringo demonstrating in Peter Jackson's "Get Back" series, the drummer leans back at his drums and falls asleep as the others continue rehearsing the song. "There wouldn't be much drumming, would there?", Paul responds. The laid-back feel of the drum-less song prompts McCartney to state, "It sounds a bit like a, sort of, dance orchestra," and as the song continues, he announces, "...and that slow foxtrot by Rita and Thomas Williams!" John chimes in with, "Peter is wearing a dark sombrero and a beard," to which Paul adds, "the husband is wearing a crimling skirt which he made himself!"

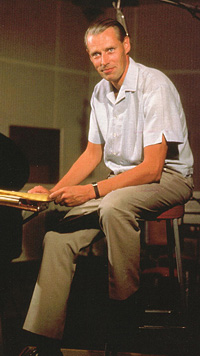

While Ringo was still sleeping, George Martin inquired why George Harrison's guitar was not being heard very well and if he was playing the proper chords to the song. He said the chords were probably not correct because he couldn't hear himself. Assistant Mal Evans then brought over a pick-up which would be attached to the body of the guitar to boost the volume. Before it can be attached, George holds the pick-up to his neck and pokes fun at the song by singing Paul's melody line with exagerated vibrato, which makes George Martin explode with laughter. While Ringo was still sleeping, George Martin inquired why George Harrison's guitar was not being heard very well and if he was playing the proper chords to the song. He said the chords were probably not correct because he couldn't hear himself. Assistant Mal Evans then brought over a pick-up which would be attached to the body of the guitar to boost the volume. Before it can be attached, George holds the pick-up to his neck and pokes fun at the song by singing Paul's melody line with exagerated vibrato, which makes George Martin explode with laughter.

After Ringo wakes up, Paul instructs producer Glyn Johns to properly record the song. Following a couple of false starts, one of which has the producer interrupting the beginning of a take to which Paul sings, “The long and winding road / yes, Glyn Johns? / what do you want?” they put in a near perfect performance with Linda Eastman and her daughter Heather looking on. Afterwards, they all file into the control room to give it a listen, which resulted in the following exchange that was also witnessed in Peter Jackson's "Get Back" series: After Ringo wakes up, Paul instructs producer Glyn Johns to properly record the song. Following a couple of false starts, one of which has the producer interrupting the beginning of a take to which Paul sings, “The long and winding road / yes, Glyn Johns? / what do you want?” they put in a near perfect performance with Linda Eastman and her daughter Heather looking on. Afterwards, they all file into the control room to give it a listen, which resulted in the following exchange that was also witnessed in Peter Jackson's "Get Back" series:

Glyn Johns: When it's mixed, as it is, I'm sure when it's mixed right, it'll be alright.

George Harrison: Yeah, but I'm really just feeling that we could tidy it up before we, like, did the one to remix.

George Martin: Paul's thinking of having strings anyway.

George Harrison: Paul, are you gonna have strings?

Paul: Dunno.

George Martin: George was saying that the piano and the electric piano tend to be doing the same thing.

George Harrison: It's like, there's only parts where you can hear the electric piano properly or the piano properly.

George Martin: Like your Leslie guitar contributes too. I mean, it is a bit in the same range as the electric piano with that vibrato on.

Paul: Yeah, I think it needs like a lot of...

John: Cleaning.

Paul: Cleaning, yeah.

George Martin: Actually, the thing is, it's a nice feel to it. It's rather like everything else we've done. This particular song doesn't need that. It needs something a little more clinical.

Paul: See, the only way I've ever heard it is, like, in my head. It's like Ray Charles band.

George Harrison: It would be nice with some brass just doing the sustaining chords, moving, holding notes.

George Martin: It's hardly Beatles mode.

Paul: Yeah, we were planning to do it anyway with a couple of numbers, just have a bit of brass and a bit of strings. That's what George was saying before. That's the bit where the Raylette's would sing it, "The long and winding road..."

George Martin: Yeah, like a chord.

Paul and George Harrison (harmonizing): "...that leads to your door..."

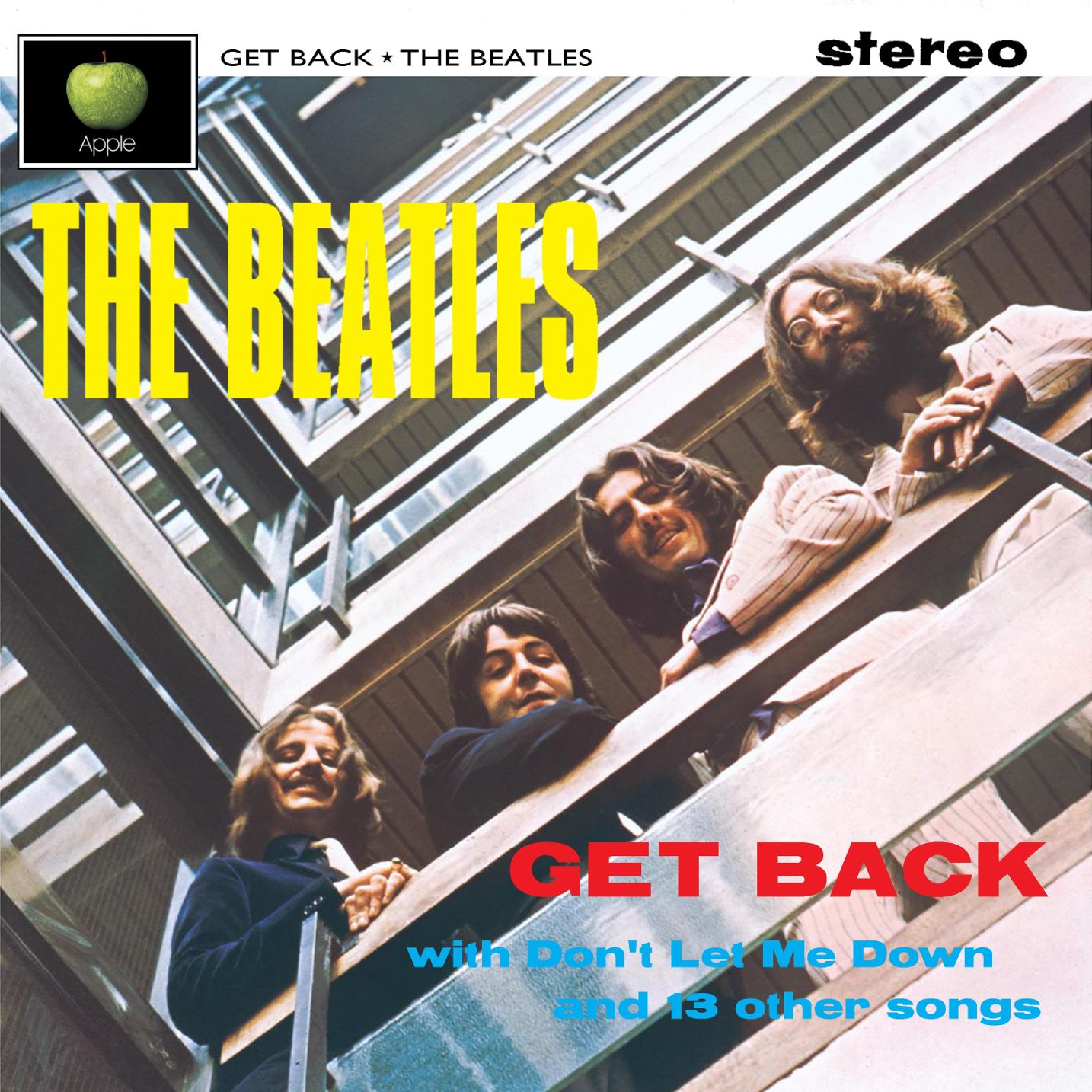

From this interchange we see that Glyn Johns was the only person that thought this recording of "The Long And Winding Road" could be used for the finished product. This, apparently, was all that really mattered because Glyn ultimately decided to choose this recording to be included on his May 1969 proposed version of the “Get Back” album, which was intended for release in the summer of that year. Surpringly, Phil Spector also chose this recording of the song to add strings and choir to for the officially released "Let It Be" album, which came out in May of 1970. This take, without any overdubs, also graced the 1996 “Anthology 3” compilation album and many 2021 Anniversary editions of the "Let It Be" album. Therefore, even though The Beatles and George Martin all disagreed with this choice, this recording of "The Long And Winding Road" that was recorded on January 26th, 1969 was the third officially recorded song for the "Let It Be" album, the first two being "For You Blue" and "Dig It." From this interchange we see that Glyn Johns was the only person that thought this recording of "The Long And Winding Road" could be used for the finished product. This, apparently, was all that really mattered because Glyn ultimately decided to choose this recording to be included on his May 1969 proposed version of the “Get Back” album, which was intended for release in the summer of that year. Surpringly, Phil Spector also chose this recording of the song to add strings and choir to for the officially released "Let It Be" album, which came out in May of 1970. This take, without any overdubs, also graced the 1996 “Anthology 3” compilation album and many 2021 Anniversary editions of the "Let It Be" album. Therefore, even though The Beatles and George Martin all disagreed with this choice, this recording of "The Long And Winding Road" that was recorded on January 26th, 1969 was the third officially recorded song for the "Let It Be" album, the first two being "For You Blue" and "Dig It."

This rendition shows John still struggling on bass while George experiments with subtle lead guitar lines during the open spaces of the vocals, as he was always prone to do, and playing rhythm chords elsewhere. Paul repeats the bridge lyrics during the second bridge in this version, partially in spoken word form, where it was usually left open as an instrumental section. John ends the song with a rising note up the frets of his bass while Paul fiddles around on piano with a further verse while Billy Preston and John goof around on their instruments. Apart from the rising bass note from John, the majority of these dalliances were lopped off for any aborted or official releases. The eight-track tape for this recording contained the following: Paul's vocal on track one, George's bare acoustic guitar on track two, Billy Preston's electric piano on track three, John's bass on track four, Ringo's drums in stereo on tracks five and six, George's acoustic guitar run through a Leslie speaker on track seven, and Paul's piano on track eight. This rendition shows John still struggling on bass while George experiments with subtle lead guitar lines during the open spaces of the vocals, as he was always prone to do, and playing rhythm chords elsewhere. Paul repeats the bridge lyrics during the second bridge in this version, partially in spoken word form, where it was usually left open as an instrumental section. John ends the song with a rising note up the frets of his bass while Paul fiddles around on piano with a further verse while Billy Preston and John goof around on their instruments. Apart from the rising bass note from John, the majority of these dalliances were lopped off for any aborted or official releases. The eight-track tape for this recording contained the following: Paul's vocal on track one, George's bare acoustic guitar on track two, Billy Preston's electric piano on track three, John's bass on track four, Ringo's drums in stereo on tracks five and six, George's acoustic guitar run through a Leslie speaker on track seven, and Paul's piano on track eight.

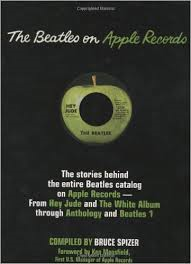

On January 27th, 1969 at Apple Studios, after Paul was feeling a bit down after their attempts at his song "Let It Be," he thought to change gears and put in more work on his other ballad for the project, introducing the tune as "The Wrong And Winding Box." Paul led the group through six rehearsals of the song which were described by Bruce Spizer in his book "The Beatles On Apple Records" as "a few deliberately off-the-wall performances, including one in which John did most of the singing and Paul mimicked Al Jolson." Afterwards, a decision was made to record a serious attempt to see if they could better the one from the previous day. It featured Ringo using brushes, many times performing fast snare drum rolls, while John came in on backing vocals twice during the lines “still they lead me back.” Thereafter, Paul's discouraged mood continued. "It's like the other one," Paul stated in reference to "Let It Be." "Slow, ballady and like they're plodding a bit...I can't, sort of, think how to do this one at all, y'know. My mind's a blank on it. I don't know. Dunno. Give up!" They moved directly into working on other songs, including recording the official released version of "Get Back," which lifted morale very nicely. On January 27th, 1969 at Apple Studios, after Paul was feeling a bit down after their attempts at his song "Let It Be," he thought to change gears and put in more work on his other ballad for the project, introducing the tune as "The Wrong And Winding Box." Paul led the group through six rehearsals of the song which were described by Bruce Spizer in his book "The Beatles On Apple Records" as "a few deliberately off-the-wall performances, including one in which John did most of the singing and Paul mimicked Al Jolson." Afterwards, a decision was made to record a serious attempt to see if they could better the one from the previous day. It featured Ringo using brushes, many times performing fast snare drum rolls, while John came in on backing vocals twice during the lines “still they lead me back.” Thereafter, Paul's discouraged mood continued. "It's like the other one," Paul stated in reference to "Let It Be." "Slow, ballady and like they're plodding a bit...I can't, sort of, think how to do this one at all, y'know. My mind's a blank on it. I don't know. Dunno. Give up!" They moved directly into working on other songs, including recording the official released version of "Get Back," which lifted morale very nicely.

Interestingly, in the control room at the end of the day, Paul stated that "the two slow ones, 'Mother Mary' and 'Brother Jesus,' they haven't happened yet," meaning that neither "Let It Be" nor "The Long And Winding Road" had been recorded properly yet. Glyn Johns, however, was still pushing for using the January 26th, 1969 recording of "The Long And Winding Road" as he had done the previous day. "I think it's very tasty," Glyn Johns explains, Paul replying, "Oh, the little version we...?" "I'm not saying you can't do it better, I'm saying it's very together," Glyn Johns insists. As stated above, Glyn Johns got his way in the end, whether Paul liked it or not. Interestingly, in the control room at the end of the day, Paul stated that "the two slow ones, 'Mother Mary' and 'Brother Jesus,' they haven't happened yet," meaning that neither "Let It Be" nor "The Long And Winding Road" had been recorded properly yet. Glyn Johns, however, was still pushing for using the January 26th, 1969 recording of "The Long And Winding Road" as he had done the previous day. "I think it's very tasty," Glyn Johns explains, Paul replying, "Oh, the little version we...?" "I'm not saying you can't do it better, I'm saying it's very together," Glyn Johns insists. As stated above, Glyn Johns got his way in the end, whether Paul liked it or not.

The next day, January 28th, 1969, saw Paul run through “The Long And Winding Road” once at the beginning of this Apple Studios rehearsal, but then attention went to other “Let It Be” songs that needed more refining. Interestingly though, The Beatles and Billy Preston fell into a slow 12-bar-blues progression that has later been referred to as “The River Rhine” because of Paul repeating the phrase “moving along by the River Rhine” as the key lyric. With Paul on bass and bluesy vocal, George on rhythm and lead guitar, Billy on electric piano and Ringo on drums, McCartney decided to delve into a portion of the lyrics of “The Long And Winding Road,” which fit the mood of this ad lib composition perfectly. The listener can here witness how the song could have developed if Paul would have kept to his original idea of modeling the tune after Ray Charles. The next day, January 28th, 1969, saw Paul run through “The Long And Winding Road” once at the beginning of this Apple Studios rehearsal, but then attention went to other “Let It Be” songs that needed more refining. Interestingly though, The Beatles and Billy Preston fell into a slow 12-bar-blues progression that has later been referred to as “The River Rhine” because of Paul repeating the phrase “moving along by the River Rhine” as the key lyric. With Paul on bass and bluesy vocal, George on rhythm and lead guitar, Billy on electric piano and Ringo on drums, McCartney decided to delve into a portion of the lyrics of “The Long And Winding Road,” which fit the mood of this ad lib composition perfectly. The listener can here witness how the song could have developed if Paul would have kept to his original idea of modeling the tune after Ray Charles.

On the following day, January 29th, 1969, it was decided that The Beatles would play an Apple rooftop concert the next day. Therefore, on this day they decided to rehearse the songs they were to perform, afterward delving into the remaining compositions that needed to be worked out thoroughly, including “The Long And Winding Road.” Before going through the various George Harrison songs that may have been deemed suitable for the project, they quickly went through two versions of "The Long And Winding Road." Before this, Paul conceded, "I don't think I can sing it like Ray Charles. I've tried that and, like, one or two nights really into it, I can hit it. But, y'know" John responded, "Oh, well, you'll just have to get the one (vocal approach) you're gonna use on the day." Paul replied, "Yeah, which is just very quiet, no energy." On the following day, January 29th, 1969, it was decided that The Beatles would play an Apple rooftop concert the next day. Therefore, on this day they decided to rehearse the songs they were to perform, afterward delving into the remaining compositions that needed to be worked out thoroughly, including “The Long And Winding Road.” Before going through the various George Harrison songs that may have been deemed suitable for the project, they quickly went through two versions of "The Long And Winding Road." Before this, Paul conceded, "I don't think I can sing it like Ray Charles. I've tried that and, like, one or two nights really into it, I can hit it. But, y'know" John responded, "Oh, well, you'll just have to get the one (vocal approach) you're gonna use on the day." Paul replied, "Yeah, which is just very quiet, no energy."

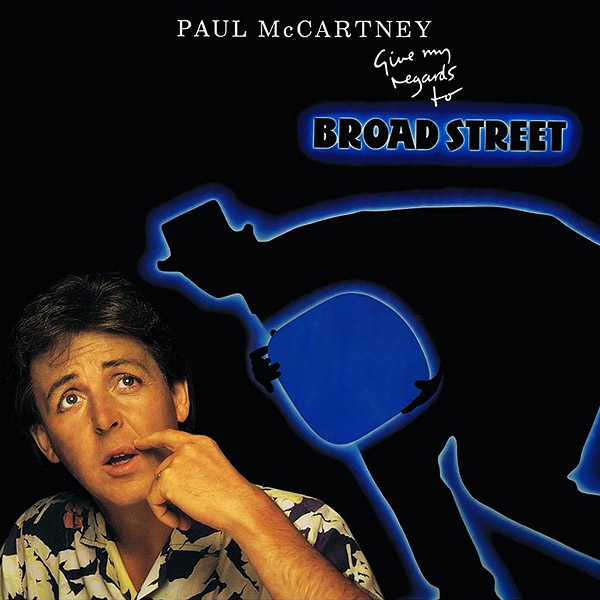

Their first attempt broke down after the first verse, Paul readdressing it by starting another rendition at the second verse. “A bit heavy on the bass, there,” Paul instructed John repeatedly during this rendition, while still trying to hone in on the perfect arrangement. We see here that Ringo has switched back to drum sticks instead of brushes, undoubtedly at Paul's request. Also, when Paul was vocalizing the solo, someone asked what he was envisioning here, to which he said, “I dunno...Ronnie Scott,” indicating a possible inclusion of a saxophone solo to be overdubbed later. This thought undoubtedly stuck in his head throughout the years since, when Paul re-recorded the song for his "Give My Regards To Broadstreet" project, he incorporated a sax player within the arrangement, which worked very nicely. Their first attempt broke down after the first verse, Paul readdressing it by starting another rendition at the second verse. “A bit heavy on the bass, there,” Paul instructed John repeatedly during this rendition, while still trying to hone in on the perfect arrangement. We see here that Ringo has switched back to drum sticks instead of brushes, undoubtedly at Paul's request. Also, when Paul was vocalizing the solo, someone asked what he was envisioning here, to which he said, “I dunno...Ronnie Scott,” indicating a possible inclusion of a saxophone solo to be overdubbed later. This thought undoubtedly stuck in his head throughout the years since, when Paul re-recorded the song for his "Give My Regards To Broadstreet" project, he incorporated a sax player within the arrangement, which worked very nicely.

Interestingly, Paul decided to change the lyrics on the next performance of this day from “Anyway you'll never know the many ways I've tried” to “you'll always know.” He apparently thought this was better, all subsequent versions including the subtly changed line “Anyway you've always known the many ways I've tried.” Since the recording chosen for the final version was recorded on January 26th, 1969, we can still say that the writing of the song was complete on that earlier date. This performance concluded with Paul stating, “It's all right,” John responding, "It's all right, you know. Between you two, you're doing all the bits that are needed." With this affirmation, they felt ready to finalize the song two days later when they would perform it in front of the cameras in the Apple basement studio. Interestingly, Paul decided to change the lyrics on the next performance of this day from “Anyway you'll never know the many ways I've tried” to “you'll always know.” He apparently thought this was better, all subsequent versions including the subtly changed line “Anyway you've always known the many ways I've tried.” Since the recording chosen for the final version was recorded on January 26th, 1969, we can still say that the writing of the song was complete on that earlier date. This performance concluded with Paul stating, “It's all right,” John responding, "It's all right, you know. Between you two, you're doing all the bits that are needed." With this affirmation, they felt ready to finalize the song two days later when they would perform it in front of the cameras in the Apple basement studio.

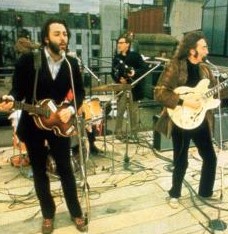

After The Beatles dedicated January 30th, 1969 to their famous last live performance on the roof of their Apple building, the following day, January 31st, 1969, was reserved for officially filming and recording three other songs from this project that were deemed unsuitable for the rooftop concert. Of interest here is a conversation among The Beatles in the control room of Apple Studios on January 30th, 1969, as seen in Peter Jackson's "Get Back" documentary series. Concerning the idea of performing "The Long And Winding Road" and the other songs not performed on the roof in their basement studio afterwards, George suggested, "We could pretend in the film that we had to get down because of (the police) and then here we are!” After The Beatles dedicated January 30th, 1969 to their famous last live performance on the roof of their Apple building, the following day, January 31st, 1969, was reserved for officially filming and recording three other songs from this project that were deemed unsuitable for the rooftop concert. Of interest here is a conversation among The Beatles in the control room of Apple Studios on January 30th, 1969, as seen in Peter Jackson's "Get Back" documentary series. Concerning the idea of performing "The Long And Winding Road" and the other songs not performed on the roof in their basement studio afterwards, George suggested, "We could pretend in the film that we had to get down because of (the police) and then here we are!”

These three songs, which were professionally recorded before the cameras in their Apple basement studio, were “Two Of Us,” “Let It Be” and “The Long And Winding Road.” While performances of the first two songs were chosen for international release, each of the many excellent renditions of “The Long And Winding Road” recorded on this day were overlooked for inclusion on the “Let It Be” album and single. Producer Glyn Johns still prefered the rougher version of the song that they recorded on January 26th, 1969, which happens to be the very day that Paul taught them the chords and first worked out the arrangement. Interestingly, as mentioned above, Phil Spector also prefered this rough early version when putting together the "Let It Be" album in March of 1970. These three songs, which were professionally recorded before the cameras in their Apple basement studio, were “Two Of Us,” “Let It Be” and “The Long And Winding Road.” While performances of the first two songs were chosen for international release, each of the many excellent renditions of “The Long And Winding Road” recorded on this day were overlooked for inclusion on the “Let It Be” album and single. Producer Glyn Johns still prefered the rougher version of the song that they recorded on January 26th, 1969, which happens to be the very day that Paul taught them the chords and first worked out the arrangement. Interestingly, as mentioned above, Phil Spector also prefered this rough early version when putting together the "Let It Be" album in March of 1970.

Nonetheless, on January 31st, 1969, after they recorded a suitable version of “Two Of Us” in a relatively short amount of time, The Beatles blew off the tension by running through many oldies, including some of their own compositions like “Run For Your Life” and Paul's “Step Inside Love.” Getting back to the work at hand, The Beatles put in many attempts at nailing down “Let It Be” before putting it aside for a while. Nonetheless, on January 31st, 1969, after they recorded a suitable version of “Two Of Us” in a relatively short amount of time, The Beatles blew off the tension by running through many oldies, including some of their own compositions like “Run For Your Life” and Paul's “Step Inside Love.” Getting back to the work at hand, The Beatles put in many attempts at nailing down “Let It Be” before putting it aside for a while.

After a lunch break, Paul rehearsed certain parts of "The Long And Winding Road" by himself for fine-tuning purposes. The Beatles then began official work on the song, the performances being designated as "take 13" through "take 19" to coincide with the movie director's clapper board takes. It should be noted, however, that there were many false starts and incomplete versions, some of these being combined together within the take numbers, which will be indicated below as 16A, 16B, 16C and so on. All in all, including partial rehearsals, it took an actual total of 19 takes to reach an acceptable recording of the song on this day. On these takes George dials back his lead guitar lines in the vocal gaps and Ringo is instructed not to tinkle around on the cymbals anymore in the verses. After a lunch break, Paul rehearsed certain parts of "The Long And Winding Road" by himself for fine-tuning purposes. The Beatles then began official work on the song, the performances being designated as "take 13" through "take 19" to coincide with the movie director's clapper board takes. It should be noted, however, that there were many false starts and incomplete versions, some of these being combined together within the take numbers, which will be indicated below as 16A, 16B, 16C and so on. All in all, including partial rehearsals, it took an actual total of 19 takes to reach an acceptable recording of the song on this day. On these takes George dials back his lead guitar lines in the vocal gaps and Ringo is instructed not to tinkle around on the cymbals anymore in the verses.

Before their first attempt at the song begins, we hear John practicing his bass part on his Fender VI Bass, George running through some scales on his Fender Telecaster, and Paul practicing a bit on the studio's Bluthner grand piano. After “take 13A' is called out, Paul leads the group through a few bars of the first verse before someone in the crew calls the song to a halt. “Take 13B” is a competent full performance of the song, flawed only by the highly rotating Leslie speaker effect on George's guitar in the solo and an overall lack in enthusiasm by the group as a whole. “OK, do it again,” Paul announces afterwards, knowing it could be done better. Before their first attempt at the song begins, we hear John practicing his bass part on his Fender VI Bass, George running through some scales on his Fender Telecaster, and Paul practicing a bit on the studio's Bluthner grand piano. After “take 13A' is called out, Paul leads the group through a few bars of the first verse before someone in the crew calls the song to a halt. “Take 13B” is a competent full performance of the song, flawed only by the highly rotating Leslie speaker effect on George's guitar in the solo and an overall lack in enthusiasm by the group as a whole. “OK, do it again,” Paul announces afterwards, knowing it could be done better.

After a bit of fumbling around on their instruments as well as Paul practicing the song's introduction, "take 14" is called out. This rendition started off well despite Paul having to deal with a moving microphone. Just after the second verse begins, McCartney pops his “p” on the lyric “pool of tears,” which prompts him to slightly pound on this piano keys and ask “Have you got a screwdriver for this mic?” After a bit of fumbling around on their instruments as well as Paul practicing the song's introduction, "take 14" is called out. This rendition started off well despite Paul having to deal with a moving microphone. Just after the second verse begins, McCartney pops his “p” on the lyric “pool of tears,” which prompts him to slightly pound on this piano keys and ask “Have you got a screwdriver for this mic?”

After the microphone problem is fixed, "take 15A" stops immediately after the second measure because of Ringo hitting the downbeat of the third measure a little early. “Let's do it again,” Paul patiently asks, instructing the drummer “just come in, don't syncopate. Just come in straight.” McCartney then immediately counts off "take 15B," which reveals the singer struggling three times to get through the first introductory measure. After he does, "take 15B" turns out to be a complete version but with many sour chords from George's guitar, which apparrently needs to be re-tuned. After the take is complete, George discusses something with Paul off microphone in which the singer responds “wrong.” Producer Glyn Johns then informs Ringo that “on the very last chord on the end of the row, the cymbals are not bass drum...the bass drum makes it a bit heavy.” After the microphone problem is fixed, "take 15A" stops immediately after the second measure because of Ringo hitting the downbeat of the third measure a little early. “Let's do it again,” Paul patiently asks, instructing the drummer “just come in, don't syncopate. Just come in straight.” McCartney then immediately counts off "take 15B," which reveals the singer struggling three times to get through the first introductory measure. After he does, "take 15B" turns out to be a complete version but with many sour chords from George's guitar, which apparrently needs to be re-tuned. After the take is complete, George discusses something with Paul off microphone in which the singer responds “wrong.” Producer Glyn Johns then informs Ringo that “on the very last chord on the end of the row, the cymbals are not bass drum...the bass drum makes it a bit heavy.”

"Take 16A" doesn't get past “The Long and...no” introduction, while "take 16B" is called to a halt when Paul hears the Major 7th chord after the lyric “to your door.” “Now what's that?” McCartney asks, which prompts George and Billy Preston to demonstrate the chord with Paul's piano. “It just sounds funny,” McCartney replies before launching into "take 16C." "Take 16A" doesn't get past “The Long and...no” introduction, while "take 16B" is called to a halt when Paul hears the Major 7th chord after the lyric “to your door.” “Now what's that?” McCartney asks, which prompts George and Billy Preston to demonstrate the chord with Paul's piano. “It just sounds funny,” McCartney replies before launching into "take 16C."

"Take 16C" is a complete version that is sung in a very spirited fashion by Paul although George's guitar still sounds out of tune. Paul vocalizes the solo in the instrumental section of the song on top of Billy Preston's keyboard work, which seems to indicate that McCartney intended to break their “no overdubs” policy and have a new solo of some sort recorded there later. After this take is complete, Paul chuckles slightly and asks, “Do it again, can we keep going?” "Take 16C" is a complete version that is sung in a very spirited fashion by Paul although George's guitar still sounds out of tune. Paul vocalizes the solo in the instrumental section of the song on top of Billy Preston's keyboard work, which seems to indicate that McCartney intended to break their “no overdubs” policy and have a new solo of some sort recorded there later. After this take is complete, Paul chuckles slightly and asks, “Do it again, can we keep going?”

They moved directly into another full version of the song before the crew could call out another take, therefore this one can be designated as "take 16D." George's guitar now appeared to be re-tuned, but Paul unfortunately played the wrong chord at the end of the third verse, which prompted him to say “yeah” and thereafter lessening the intensity of his vocal performance because he knew this take wasn't going to make the grade. “There were a couple of cock-ups in that, weren't there?” he asked after it concluded. They moved directly into another full version of the song before the crew could call out another take, therefore this one can be designated as "take 16D." George's guitar now appeared to be re-tuned, but Paul unfortunately played the wrong chord at the end of the third verse, which prompted him to say “yeah” and thereafter lessening the intensity of his vocal performance because he knew this take wasn't going to make the grade. “There were a couple of cock-ups in that, weren't there?” he asked after it concluded.